List of military leaders in the Eureka Rebellion

Template:Eureka Rebellion sidebar

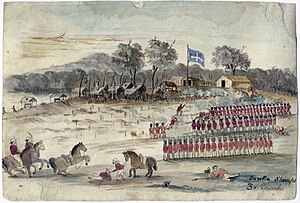

This is an incomplete list of the military leaders of the British colonial forces of Australia and the Eureka Stockade rebel garrison in the 1851-1854 Eureka Rebellion on the Victorian goldfields. The fighting at Ballarat on 3 December 1854 resulted in at least 27 deaths and many injuries, the majority of casualties being rebels. The miners had various grievances, chiefly the cost of mining permits and the officious way the system was enforced. There was an armed uprising in Ballarat where tensions were brought to a head following the death of miner James Scobie. On 30 November 1854, the Eureka Flag was raised during a paramilitary display on Bakery Hill that resulted in the formation of rebel companies and the construction of a crude battlement on the Eureka lead.

Battle of the Eureka Stockade[edit]

Following the oath swearing and Eureka Flag raising ceremony on Bakery Hill, about 1,000 rebels marched in double file to the Eureka lead, where the Eureka Stockade was constructed over the next few days. [1][2] It consisted of pit props held together as spikes by rope and overturned horse carts. Raffaello Carboni described it in his 1855 memoirs as being "higgledy piggledy".[3] It encompassed an area said to be one acre; however, that is difficult to reconcile with other estimates that have the dimensions of the stockade as being around 100 feet (30 m) x 200 feet (61 m).[4] Contemporaneous representations vary and render the stockade as either rectangular or semi-circular.[5] Testimony was heard at the high treason trials for the Eureka rebels that the stockade was four to seven feet high in places and was unable to be negotiated on horseback without being reduced.[6][note 1]

Lieutenant governor Charles Hotham feared that the goldfield's terrain would greatly favour the rebel snipers. Ballarat gold commissioner Robert Rede would instead order an early morning surprise attack on the rebel camp.[9] Carboni details the rebel dispositions along:

The shepherds' holes inside the lower part of the stockade had been turned into rifle-pits, and were now occupied by Californians of the I.C. Rangers' Brigade, some twenty or thirty in all, who had kept watch at the 'outposts' during the night.[10]

The location of the stockade has been described by Eureka veteran John Lynch as "appalling from a defensive point of view" as it was situated on "a gentle slope, which exposed a sizeable portion of its interior to fire from nearby high ground".[11][note 2]

In the early hours of 1 December, the rebels were observed to be massing on Bakery Hill, but a government raiding party found the area vacated. The riot act was read to a mob that had gathered around Bath's Hotel, with mounted police breaking up the unlawful assembly. A three-man miner's delegation met with Commissioner Rede to present a peace proposal; however, Rede was suspicious of the chartist undercurrent of the anti-mining tax movement and rejected the proposals as being the way forward.[15]

The rebels sent out scouts and established picket lines in order to have advance warning of Rede's movements and a request for reinforcements to the other mining settlements.[16] The "moral force" faction had withdrawn from the protest movement as the men of violence moved into the ascendancy. The rebels continued to fortify their position as 300-400 men arrived from Creswick's Creek, and Carboni recalls they were: "dirty and ragged, and proved the greatest nuisance. One of them, Michael Tuohy, behaved valiantly".[17] Once foraging parties were organised, there was a rebel garrison of around 200 men. Amid the Saturday night revelry, low munitions, and major desertions, Lalor ordered that any man attempting to leave the stockade be shot.[18]

Ballarat gold commissioner Robert Rede planned to send the combined military police formation of 276 men under the command of Captain John Thomas to attack the Eureka Stockade when the rebel garrison was observed to be at a low watermark. The police and military had the element of surprise timing their assault on the stockade for dawn on Sunday, the Christian Sabbath day of rest. The soldiers and police marched off in silence at around 3:30 am Sunday morning after the troopers had drunk the traditional tot of rum.[19] The British commander used bugle calls to coordinate his forces. The 40th regiment was to provide covering fire from one end, with mounted police covering the flanks. Enemy contact began at approximately 150 yards as the two columns of regular infantry and the contingent of foot police moved into position.[20]

According to military historian Gregory Blake, the fighting in Ballarat on 3 December 1854 was not one-sided and full of indiscriminate murder by the colonial forces. In his memoirs, one of Lalor's captains, John Lynch, mentions "some sharp shooting".[21] For at least 10 minutes, the rebels offered stiff resistance, with ranged fire coming from the Eureka Stockade garrison such that Thomas's best formation, the 40th regiment, wavered and had to be rallied. Blake says this is "stark evidence of the effectiveness of the defender's fire".[22]

The rebels eventually ran short of ammunition, and the government forces resumed their advance. The Victorian police contingent led the way over the top as the forlorn hope in a bayonet charge.[20][23] Carboni says it was the pikemen who stood their ground that suffered the heaviest casualties,[23] with Lalor ordering the musketeers to take refuge in the mine holes and crying out, "Pikemen, advance! Now for God's sake do your duty".[24] There were twenty to thirty Californians at the stockade during the battle. After the rebel garrison had already begun to flee and all hope was lost, a number of them gamely joined in the final melee bearing their trademark Colt revolvers.[25]

British army commanders[edit]

The government camp at Ballarat was barely fortified and under the command of Captain John Thomas. He led the attack on the Eureka Stockade, with Captain Charles Pasley as his second in command. The government forces at the Ballarat camp were under the immediate command of resident gold commissioner Robert Rede. Overall command was exercised by the executive lieutenant governor Charles Hotham and the high commander of the British colonial forces in Australia, Major General Sir Robert Nickle.

There were two British regiments, the 12th and 40th, the latter consisting of infantry and a mounted column. There was also a contingent of Victorian mounted troopers and foot police. The strength of the various formations in the Ballarat government camp at the time of the armed uprising was: 40th regiment (infantry): 87 men; 40th regiment (mounted): 30 men; 12th regiment (infantry): 65 men; mounted police: 70 men; and the foot police: 24 men.[26] By the beginning of December, the police contingent at Ballarat had been surpassed by the number of soldiers from the 12th and 40th regiments.

Lieutenant governor[edit]

| Name | Period of service in the rank, promotions and previous military experience. Termination of service | Commentary | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

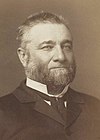

Charles Hotham | Hotham served as lieutenant governor and, later, governor of Victoria, Australia, from 22 June 1854 to 31 December 1855.[27] | He feared that the "network of rabbit burrows" on the goldfields would prove readily defensible as his forces "on the rough pot-holed ground would be unable to advance in regular formation and would be picked off easily by snipers," which led to the decision to move into position in the early morning for a surprise attack on the Eureka Stockade.[9] |

Supreme commander of military forces in Australia[edit]

| Name | Period of service in the rank, promotions and previous military experience. Termination of service | Commentary | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Robert Nickle | Nickle was a major general and the commander-in-chief of the colonial forces of Australia at the time of the attack on the Eureka Stockade. Nickle had previously seen action during the 1798 Irish rebellion.[28] | He had dispatched additional soldiers to Ballarat in the lead-up to the armed uprising. Nickle sent out from Melbourne with a force of 800 men, which included "two field pieces and two howitzers" that arrived after the rebels had made their last stand.[12][13][28] |

Resident commissioners[edit]

| Name | Period of service in the rank, promotions and previous military experience. Termination of service | Commentary | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Robert William Rede | Rede was appointed to the Victorian Goldfields Commission in October 1852. From June 1854 to January 1855, he was posted to Ballarat and had responsibility for the government camp during the Battle of the Eureka Stockade.[29] | Following the armed uprising, Rede was recalled from Ballarat and kept on full pay until 1855. Rede served as the sheriff at Geelong (1857), Ballarat (1868), and Melbourne (1877) and was the Commandant of the Volunteer Rifles, being the second-in-command at Port Phillip. In 1880, he was sheriff at the trial of Ned Kelly and an official witness to his execution.[30] |

| James Johnston | Johnston was appointed as a magistrate and the assistant gold commissioner for the gravel pits on the Ballarat goldfields in November 1853.[31] | His responsibilities included organising licence inspections and hearing relatively minor infringements. Johnston was on the bench that presided over the inquest into the death of James Scobie, which sparked the armed uprising. He dissented from the other members of the panel and found that James Bentley and others should not be honourably discharged.[31] |

Lieutenant colonels[edit]

40th Regiment

| Name | Period of service in the rank, promotions and previous military experience. Termination of service | Commentary | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thomas James Valiant | Valiant was at the Eureka Stockade as lieutenant colonel of the 40th regiment.[32] | Technically, the highest-ranking officer of the colonial forces in the battle.[33] |

Majors[edit]

40th Regiment

| Name | Period of service in the rank, promotions and previous military experience. Termination of service | Commentary | |

|---|---|---|---|

| John Martin Bladin Neil | Neil was a major in the 40th regiment at the Eureka Stockade.[34] | — |

Captains[edit]

12th regiment

| Name | Period of service in the rank, promotions and previous military experience. Termination of service | Commentary | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arthur Atkinson | Atkinson was a captain with the 12th regiment at Ballarat in 1854. On the day of the battle, he was assigned to guard the government camp in case the rebels attacked. | Atkinson arrived in Victoria aboard the Empress Eugenie on 3 November 1854. He does not appear on the army lists of 1854 or 1856 or at any time before 1881. Atkinson was probably attached to the 12th regiment from another, possibly colonial unit. [35] | |

| William Henry Queade | Queade was a captain with the 12th Regiment at the Eureka Stockade.[36] | — |

40th regiment

| Name | Period of service in the rank, promotions and previous military experience. Termination of service | Commentary | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

John Wellesley Thomas | Thomas was a captain with the 40th regiment and commanded the colonial forces at the Eureka Stockade. He was a top adviser to Robert Rede. Thomas received his commission in 1839 and had seen action in Afghanistan and China. In 1862, he was promoted to colonel and in 1877, he became a major general. Thomas was an honorary lieutenant general when he retired in 1881. In 1882, he was appointed to the colonelcy of the Hampshire Regiment, and in 1904 was made a Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath.[37] | Thomas was wounded in the battle but did not withdraw and relinquish command to Inspector Carter until after the stockade had fallen. He ordered Carter to burn down the stockade while he escorted the detainees to Melbourne. Later described the battle as "a trifling affair". The Maharajpoor Star, which he was awarded in 1843 and may have worn on the day, is held by the Ballarat Gold Museum, and his British Pattern 1845 infantry sword is at the Australian War Memorial.[37] |

| Henry Wise | Wise was a captain with the 40th regiment at the Eureka Stockade. He became a captain in the British army and arrived in Victoria with the 40th (the 2nd Somersetshire) Regiment of Foot in 1852.[38] | The highest ranking member of the colonial forces killed as a result of the battle, Wise was the son of Henry Christopher Wise, an English Conservative politician, and his first wife, Harriett Skipwith.[38] | |

| Thomas LK Nelson | Nelson was a captain with the 40th Regiment at the Eureka Stockade. He joined the British army in 1831 as an ensign and was raised to lieutenant in 1836. Nelson saw active service in the first Afghan war and was made adjutant of the regiment in 1842. In 1846, he was promoted to captain and, in 1856, became a major. | — | |

| John Warren White | Warren was a captain with the 40th regiment at the Eureka Stockade.[39] | He was part of the military convoy that arrived in Ballarat on 28 November 1854. It is said that during the battle, White cornered a rebel miner within the stockade.[40] |

Assistant engineer[edit]

| Name | Period of service in the rank, promotions and previous military experience. Termination of service | Commentary | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Charles Pasley | Captain Charles Pasley was the colonial engineer and offered his services to Hotham as the rebellion was heading for an armed uprising. He served as aide-de-camp to Captain John Thomas, arriving in Ballarat on 28 November 1854. Pasley commanded the centre during the government assault on the Eureka Stockade.[41] | Eyewitness accounts of the battle tell how women ran forward and threw themselves over the injured to prevent indiscriminate killing. As second in command, Captain Pasley gave the order to withdraw and threatened to shoot anyone involved in murdering prisoners.[41] |

Lieutenants[edit]

12th Regiment

| Name | Period of service in the rank, promotions and previous military experience. Termination of service | Commentary | |

|---|---|---|---|

| John Hall | |||

| George Richard Littlehailes | |||

| William Henry Paul (no 1209) |

40th Regiment

| Name | Period of service in the rank, promotions and previous military experience. Termination of service | Commentary | |

|---|---|---|---|

| George Owen Bowdler | |||

| John Edward Broadhurst | |||

| Thomas McPherson Bruce-Gardyne | |||

| Thomas McPherson Bruce-Gardyne | |||

| Charles Henry Hall | |||

| Bailey Richards |

Ensigns[edit]

40th Regiment

| Name | Period of service in the rank, promotions and previous military experience. Termination of service | Commentary | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arthur Marquand Champion Mollers |

Victorian police commanders[edit]

The Victorian colonial police force of the 1850s operated as an armed paramilitary gendarmerie where troopers and police were garrisoned at central locations, such as the government camp in Ballarat, and there was no interaction with the civilian population. To cope with the expansion of the mining industry, the Victorian government resorted to recruiting at least 130 former convicts from Tasmania who were prone to brutal means. They would get a fifty per cent commission from all fines imposed on unlicensed miners and sly grog sellers. Plainclothes officers enforced prohibition, and those involved in the illegal sale of alcohol were initially handed 50-pound fines. There was no profit for police from subsequent offences, that were instead punishable by months of hard labour. This led to the corrupt practice of police demanding blackmail of 5 pounds from repeat offenders.[42][43][44] By January 1853, there were 230 mounted police throughout Victoria. By 1855, the number had risen to 485, including nine mounted detectives.[45]

There were no known casualties among the Victorian police contingent who led the way over the top as the forlorn hope in a bayonet charge at the Eureka Stockade. George Webster, the chief assistant civil commissary and magistrate, testified in the 1855 Victorian high treason trials that upon entering the stockade, the besieging forces "immediately made towards the flag, and the police pulled down the flag".[46] John King testified, "I took their flag, the southern cross, down – the same flag as now produced."[47] In his report dated 14 December 1854, Captain John Thomas mentioned "the fact of the Flag belonging to the Insurgents (which had been nailed to the flagstaff) being captured by Constable King of the Force".[48] King had volunteered for the honour while the battle was still raging.[49] W. Bourke, a miner residing about 250 yards from the stockade, recalled that: "The police negotiated the wall of the Stockade on the south-west, and I then saw a policeman climb the flag pole. When up about 12 or 14 feet the pole broke, and he came down with a run".[50]

Inspectors[edit]

| Name | Period of service in the rank, promotions and previous military experience. Termination of service | Commentary | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Henry Foster | Foster was a police inspector in Ballarat.[51] | — |

Senior sub inspectors[edit]

Mounted police

| Name | Period of service in the rank, promotions and previous military experience. Termination of service | Commentary | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thomas Langley | Langley was a senior sub-inspector of the mounted police at the Eureka Stockade.[52] | He was involved in the arrest of Timothy Hayes at 2:30 am on the day of the battle about 300 yards away from the stockade. He testified at the committal hearings of Hayes and John Joseph. Langley then appeared in the high treason trials, where Hayes was one of the defendants.[52] |

Sub inspectors[edit]

Foot police

| Name | Period of service in the rank, promotions and previous military experience. Termination of service | Commentary | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Charles Jeffreys Carter | Carter was a sub-inspector and served with the foot police at the Eureka Stockade on 3 December 1854.[53] | ||

| Samuel Stackpole Furnell | Furnell was a sub-inspector and served with the foot police at the Eureka Stockade on 3 December 1854.[54] | ||

| John Sadlier | Sadlier was a sub-inspector of police at Ballarat in 1854.[55] | In his 1898 memoirs, he recalls being at the police headquarters in Flinders Street, Melbourne, on the day of the battle. Sadlier recalls his concern as small crowds gathered nearby as news of the armed uprising reached the capital. He was involved in the hunt for the Kelly gang in 1878-1880. As a police superintendent, Sadlier was in command for part of the siege at Glenrowan, where Ned Kelly was captured.[55] | |

| Maurice Frederick Ximenes | Ximenes was a sub-inspector with the police at the Eureka Stockade.[56] | He was present at the burning of the Eureka Hotel. He ordered some of his subordinates to hide inside the hotel and lent his horse to John Bentley so he could flee the scene. On 30 November 1854, Ximenes led the final provocative licence inspection four days before the fall of the Eureka Stockade. Inspector Henry Foster said it would be dangerous for Ximenes to be "seen alone on the diggings". John Sadleir wrote that Ximenes was also less than popular in the government camp. On one occasion, he went a few hundred yards from his tent, and when he returned, the sentry asked for the password, which Ximenes did not know. When the sentry persisted, Ximenes ran into his tent and drove his bayonet into a nearby tent pole behind him. Sadlier states, "it was all a bit of spite, but the police officer took good care in the future to learn the password.[56] |

Mounted police

| Name | Period of service in the rank, promotions and previous military experience. Termination of service | Commentary | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hussey Chomley | Chomley was a sub-inspector and second in command of a police detachment kept in reserve at the Eureka Stockade on 3 December 1854.[57] | — | |

| Ladislaus Kossak | Kossak was a police sub-inspector at the Eureka Stockade.[58] | He commanded the 70 Victorian police alongside Samuel Furnell, Thomas Langley, and Hussey Chomley during the battle.[58] | |

| James Langley | Langley was a sub-inspector with the mounted police at the Eureka Stockade.[59][60] | — | |

| Henry Moore | Moore was a sub-inspector of police at Ballarat in 1854.[61] | On 30 November 1854, Moore witnessed Chapman point a pistol at some troopers and gave orders that the demonstrator be taken into custody.[62][63] |

Lieutenants[edit]

Mounted police

| Name | Period of service in the rank, promotions and previous military experience. Termination of service | Commentary | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gerald De Courcy Hamilton | Hamilton was a lieutenant and adjutant of the gold-mounted police in Ballarat at the time of the battle.[64] |

Sergeant majors[edit]

Foot police

| Name | Period of service in the rank, promotions and previous military experience. Termination of service | Commentary | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Robert Milne | Milne was a sergeant major with the foot police at Ballarat in October and November 1854.[65] | He was suspected of accepting bribes from sly grog sellers on the goldfields. It was resolved at a meeting of the Ballarat Reform League that Milne be removed on the grounds that he had perjured himself before the board of enquiry into the burning of the Eureka Hotel and the death of James Scobie. He was the fourth witness to appear on 3 November 1854. A week later, Milne was recalled to clarify a few matters. Lieutenant Governor Charles Hotham dismissed him on 20 November 1854.[65] |

Sergeants[edit]

Foot police

| Name | Period of service in the rank, promotions and previous military experience. Termination of service | Commentary | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Robert McLister | McLister was a police sergeant in Ballarat in 1854.[66] | In 1858, he was a gold miner living in Geelong, the year his wife, Catherine Fenton of County Donegal, Ireland, died.[67] | |

| Thomas Milne | Milne was a police sergeant at the Eureka Stockade.[68] | At the time of the battle, he had been posted to Ballarat for about four months.[69] | |

| Edward Viret | Viret was a police sergeant at the Eureka Stockade.[70] | He testified at the board of enquiry into the burning of the Eureka Hotel and the committal hearings in the high treason trials.[71] |

Mounted police

| Name | Period of service in the rank, promotions and previous military experience. Termination of service | Commentary | |

|---|---|---|---|

| John Gillman | Gillman was a sergeant in the mounted police at the Eureka Stockade.[72] | He testified at Bryant's committal hearing that he took him prisoner after a struggle where Gillman sustained a wound to his head by a sword.[72] | |

| William Graham | Graham testified at the committal hearings that he was a sergeant of the mounted police at Ballarat on 30 November 1854.[73] | He was on the scene when a crowd of miners began throwing stones at the police, and a miner named Chapman aimed a pistol at him that was later found to be loaded.[74][75] | |

| Michael Lawler | Lawler was a sergeant with the mounted police at the Eureka Stockade.[76] | He was present during the burning of Bentley's Hotel on 17 October 1854, later giving testimony implicating Henry Westoby. Lawler charged the flank of the stockade, and it is believed that he shot and wounded Peter Lalor.[76] |

Rebel commanders[edit]

Common estimates for the size of the Eureka Stockade garrison at the time of the attack on 3 December 1854 range from 120 to 150 men.[77][78][7]

According to rebel commander in chief Peter Lalor's reckoning: "There were about 70 men possessing guns, 30 with pikes and 30 with pistols, but many had no more than one or two rounds of ammunition. Their coolness and bravery were admirable when it is considered that the odds were 3 to 1 against".[79] Lalor's command was riddled with informants, and Rede was kept well advised of his movements, particularly through the work of government agents Henry Goodenough and Andrew Peters, who were embedded in the rebel garrison.[80][81]

Initially outnumbering the government camp considerably, Lalor had already devised a strategy where "if the government forces come to attack us, we should meet them on the Gravel Pits, and if compelled, we should retreat by the heights to the old Canadian Gully, and there we shall make our final stand".[82] On being brought to battle that day, Lalor stated: "we would have retreated, but it was then too late".[79]

Commander in chief[edit]

| Name | Period of service in the rank, promotions and previous military experience. Termination of service | Commentary | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Peter Lalor | Lalor mounted the stump armed with a rifle and declared "Liberty" at the 30 November 1854 meeting on Bakery Hill. He called for the formation of paramilitary companies and presided over the Eureka Flag raising and oath-swearing ceremonies. Lalor was wounded in action at the Battle of the Eureka Stockade on 3 December 1854.[83] | At his first public appearance, Lalor acted as secretary for the 17 November 1854 meeting that led to the burning of Bentley's Hotel and moved in favour of establishing a central rebel executive.[84] Raffaello Carboni recalls a meeting in Diamond's store where he was elected as "president" and "commander in chief" of the rebel camp.[85] Lalor was hidden and secreted out of the fallen stockade by supporters. He remained on the run until a general amnesty was granted in May 1855. Lalor became a member of parliament and later served as a minister of the crown and Speaker of the Victorian Legislative Assembly. |

Secretary of war[edit]

| Name | Period of service in the rank, promotions and previous military experience. Termination of service | Commentary | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alfred Black | Black was the rebel secretary of war at the Eureka Stockade.[86] | He was responsible for writing a list of the rebel captains who had stepped forward at the 30 November 1854 oath swearing and Eureka Flag raising ceremony at Bakery Hill.[86] |

Colonels, captains and lieutenants[edit]

It appears that the terms "captain" and "lieutenant" were used interchangeably within the Eureka Stockade garrison. The front cover of Raffaello Carboni's 1855 The Eureka Stockade features a rendition of the Eureka Flag with diamond-shaped stars and the words "When Ballarat unfurled the Southern Cross, the bearer was Toronto's Captain Ross". Yet Peter Lalor's casualty list records "Lieutenant Ross" as "wounded and since dead". It appears that Frederick Vern was also more commonly known as a rebel "colonel" instead.

| Name | Period of service in the rank, promotions and previous military experience. Termination of service | Commentary | |

|---|---|---|---|

| George Black | Black was one of Lalor's captains who had been sent to go to Creswick Creek to raise more support for the rebellion. The Cyclopedia of Australisia states that he "was at Ballarat at the Eureka outbreak, which he did something to bring about, but was not in the stockade at the time of the attack".[87] | Black was a Chartist and influential member of the Ballarat Reform League. He bought and edited the radical Ballarat newspaper, the Diggers Advocate, founded by George Thompson and Henry Holyoake. The Diggers Advocate played an important part in the prelude to the Eureka Rebellion. Black proposed the motion in favour of adult male suffrage and full and fair representation at the Ballarat Reform League meeting at Bakery Hill on 11 November 1854 and served as the league's secretary. Initial reward posters issued by the Victorian government offered a 400-pound reward for information about the whereabouts of "Lawler and Black".[87][88] | |

|

Henry Ross | Ross was one of the captains of the rebel garrison. He was present at the oath-swearing and Eureka flag-raising ceremony at Bakery Hill on 30 November 1854. Ross acted as the Eureka Flag bearer at the head of about 1,000 rebels who marched in double file from Bakery Hill to the Eureka lead, where the stockade was situated.[1][2] He received a groin injury during the battle while in the vicinity of the flag pole and died later that day after being taken to the Star Hotel.[89] | There is a popular tradition where the flag design is credited to Ballarat Reform League member Henry Ross who was originally from Toronto, Canada. A. W. Crowe recounted in 1893 that "it was Ross who gave the order for the insurgents' flag at Darton and Walker's".[90] Crowe's story is confirmed in that there were advertisements in the Ballarat Times dating from October–November 1854 for Darton and Walker, manufacturers of tents, tarpaulin and flags, situated at the Gravel Pits.[91] |

| John Lynch | One of Peter Lalor's captains, he helped to conceal the rebel leader in a hole with slabs. He was arrested later that day and discharged at the committal hearings.[92] | Lynch returned to Ballarat to deliver an oration for the second anniversary of the battle. His memoirs were published in the Austral Light from October 1893 to March 1894.[92] | |

| Robert Burnete | Burnete was one of Peter Lalor's rebel captains in command of the "Independent Californian Rangers Revolver Brigade".[93] | He later claimed to have fired the first shot of the battle by either side, which killed Captain Wise. Carried a rifle.[93] | |

| James Herbert McGill | McGill was an American who commanded the "Californian Rifle Brigade". He mobilised 200 members of the rebel garrison and established the stockade sentry system. In a fateful decision, McGill left with most of his force to intercept rumoured British reinforcements en route from Melbourne.[94] | In the aftermath of the battle, McGill fled from Ballarat by stagecoach while dressed as a woman.[94] | |

| Michael Hanrahan | Hanrahan was chosen as the captain of the pikemen at the Eureka Stockade. In the days leading up to the battle, he was leading small groups of pikemen along the road to Melbourne, looking to interdict and delay any opposing forces converging on the stockade. After waiting all day on 3 December 1854, the pikemen returned to discover that the stockade had fallen.[95] | Later felt ashamed of his participation in the Eureka Rebellion and yet kept a firearm hidden in a wall in his house.[95] | |

| Edward Thonen | Thonen was a Prussian who served as one of Lalor's rebel captains and was killed in action during the battle. Carboni records that amid the shooting, "Ross and his division northward and Thonen and his division southward, and both in front of the gully, under cover of the slabs, answered with such a smart fire".[96] | Thonen was present at the meeting where Lalor was confirmed as leader and stood as seconder of the motion. Was a blacksmith and pike manufacturer for the Eureka Stockade garrison. He came to the goldfields as a lemonade seller and was known as a strong chess player.[95] | |

| Frederick Vern | The fortification of the Eureka lead was apparently overseen by Vern, who had apparently received instruction in military methods. In his memoirs, John Lynch stated that his "military learning comprehended the whole system of warfare ... fortification was his strong point".[97] | Vern gave fiery speeches at mass protest meetings, and Carboni says he boasted of being able to form a company of German miners. Later accused of fleeing the stockade at the first sign of trouble and is suspected of being a double agent.[98] | |

| Timothy Hayes | Hayes was one of the mining tax protest movement's key agitators. Chaired the 29 November 1854 meeting on Bakery Hill, where the Eureka Flag was first displayed, and mining permits were burned. He incited the crowd, shouting from the platform, "Are you ready to die?" Carboni mentions Hayes as being present at the meeting in Diamond's store where Lalor was confirmed as rebel commander-in-chief.[99] | Hayes was detained about 100 yards from the Eureka Stockade after the battle and taken to Melbourne. Put on trial for high treason and acquitted. Subsequenly supported Peter Lalor's parliamentary nomination.[100] | |

| Patrick Curtain | Carboni records that Curtain gave him his iron pike in exchange for Carboni's sword when he was initially chosen as captain of the pikemen. The Eureka Encyclopedia says he appointed Michael Hanrahan as his lieutenant.[101] Later, Carboni mentions that Hanrahan had been made captain of the pikemen and Curtain was his lieutenant. | Curtain's store was situated inside the stockade and was destroyed in the fighting, and he made a claim for compensation.[101] | |

| John Manning | Manning was a journalist who Carboni mentions as being present at the meeting where Peter Lalor was confirmed as rebel leader. Inspector Carter discovered him in the stockade's armoury when he stormed the tent. Carter arrested Manning himself and placed him into the custody of Lieutenant Richards of the 40th Regiment.[102] | Manning was subsequently indicted and acquitted in the 1855 Victorian High Treason trials.[102] | |

| Luke Sheehan | Sheehan was one of the rebel captains leading the pikemen at the Eureka Stockade. Avoided capture by the authorities.[103] | Listed as "wounded and since recovered" in Lalor's casualty report.[103] | |

| Raffaello Carboni | Acted as Lalor's interpreter when dealing with some of the European miners. He was an eyewitness to the battle, seeking shelter in the chimney of his dwelling that was nearby the stockade.[104] | Like many of the immigrant miners, Carboni was involved in the European Revolutions of 1848. He was indicted and acquitted in the 1855 Victorian High Treason trials. Eureka folklore is deeply indebted to Carboni, who published the only full-length eyewitness account of the Eureka Rebellion in 1855. Among other things, he documents the rebel command structure.[104] | |

| Adolfus Lessman | Lessman was a German from Hanover. On 2 December 1854, Peter Lalor sent Lessman for a raid on local storekeepers. He was a lieutenant of the rifleman at the Eureka Stockade and was slightly wounded in the battle.[105][106] | To mark the second anniversary of the battle, he carried a garland of flowers in a procession.[105][107] |

See also[edit]

- List of colonial forces in the Eureka Rebellion

- List of detainees at the Eureka Stockade

- List of Eureka Stockade defenders

- List of notable civilians in the Eureka Rebellion

- List of notable public officials in the Eureka Rebellion

- List of Victorian police in the Eureka Rebellion

Notes[edit]

- ↑ Peter Lalor himself said the wooden structure was never meant to be a fortress, saying "it was nothing more than an enclosure to keep our own men together, and was never erected with an eye to military defence".[7] However Peter FitzSimons says that Lalor may have downplayed the fact that the Eureka Stockade may have been intended as something of a fortress, at a time when "it was very much in his interests" to do so.[8]

- ↑ A detachment of 800 men, which included "two field pieces and two howitzers" under the commander in chief of the British forces in Australia, Major General Sir Robert Nickle, who had seen action during the 1798 Irish rebellion, arrived after the insurgency had been put down.[12][13] In 1860, Withers stated in a lecture that "The site was most injudicious for any purpose of defence as it was easily commanded from adjacent spots, and the ease with which the place could be taken was apparent to the most unprofessional eye".[14]

References[edit]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, p. xiii, 196.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Carboni 1855, p. 59.

- ↑ Carboni 1855, pp. 77, 81.

- ↑ FitzSimons 2012, p. 648, note 12.

- ↑ Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, pp. 190-191.

- ↑ The Queen v Joseph and others, 29 (Supreme Court of Victoria 1855).

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Historical Studies: Eureka Supplement 1965, p. 37.

- ↑ FitzSimons 2012, p. 648, footnote 13.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Three Despatches From Sir Charles Hotham 1978, p. 2.

- ↑ Carboni 1855, p. 96.

- ↑ Blake 2012, p. 88.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Three Despatches From Sir Charles Hotham 1978, p. 7.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Blake 1979, p. 93.

- ↑ Harvey 1994, p. 24.

- ↑ MacFarlane 1995.

- ↑ Withers 1999, p. 94.

- ↑ Carboni 1855, pp. 78-79.

- ↑ Withers 1999, pp. 116-117.

- ↑ "Eureka Stockade | Ergo". ergo.slv.vic.gov.au. Retrieved 2022-08-24.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Thomas, John Wellesley (3 December 1854). Captain Thomas reports on the attack on the Eureka Stockade to the Major Adjutant General (Report). Archived from the original on 4 April 2019. Retrieved 7 December 2020 – via Public Record Office Victoria. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ Lynch 1940, p. 30.

- ↑ Blake 2012, p. 133.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Carboni 1855, p. 98.

- ↑ Blake 1979, p. 81.

- ↑ Blake 2012, pp. 136-138.

- ↑ Withers 1999, p. 111.

- ↑ Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, pp. 275-278.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, pp. 397-398.

- ↑ Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, pp. 422-423.

- ↑ Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, p. 443.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, p. 292.

- ↑ Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, p. 519.

- ↑ Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, pp. 77-79.

- ↑ Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, pp. 389-390.

- ↑ Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, p. 22.

- ↑ Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, p. 437.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, pp. 503-504. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "FOOTNOTECorfieldWickhamGervasoni2004503-504" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 38.0 38.1 Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, pp. 548-549.

- ↑ Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, p. 79.

- ↑ Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, p. 79, 538.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, pp. 420-421.

- ↑ Clark 1987, p. 67.

- ↑ Barnard 1962, p. 260.

- ↑ "Alcohol on the Goldfields". Sovereign Hill. 21 February 2014. Retrieved 18 June 2022.

- ↑ Blake 2009, p. 75.

- ↑ The Queen v Joseph and others, 35 (Supreme Court of Victoria 1855).

- ↑ "Continuation of the State Trials". The Sydney Morning Herald. Sydney. 5 March 1855. p. 3. Retrieved 17 November 2020 – via Trove.

- ↑ Thomas, John Wellesley (14 December 1854). Capt. Thomas' report – Flag captured (Report). Colonial Secretary's Office. Archived from the original on 12 April 2019. Retrieved 7 December 2020 – via Public Record Office Victoria. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ FitzSimons 2012, p. 477.

- ↑ Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, pp. 66-67.

- ↑ Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, p. 209.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, p. 323.

- ↑ Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, pp. 107-108.

- ↑ Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, pp. 212-213.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, p. 458.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, p. 556.

- ↑ Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, pp. 114-115.

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, pp. 313-314.

- ↑ https://eurekapedia.org/James_Langley

- ↑ Oakleigh Leader, 15 December 1894.

- ↑ http://www.eurekapedia.org/William_Nevil

- ↑ https://eurekapedia.org/Henry_Moore

- ↑ http://www.eurekapedia.org/William_Nevil

- ↑ Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, pp. 245-246.

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, p. 377.

- ↑ https://eurekapedia.org/Robert_McLister

- ↑ https://eurekapedia.org/Robert_McLister

- ↑ https://eurekapedia.org/Thomas_Milne

- ↑ https://eurekapedia.org/Thomas_Milne

- ↑ https://eurekapedia.org/Edward_Viret

- ↑ https://eurekapedia.org/Edward_Viret

- ↑ 72.0 72.1 Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, p. 220.

- ↑ https://eurekapedia.org/William_Graham_(1)

- ↑ https://eurekapedia.org/William_Graham_(1)

- ↑ The Argus, 20 January 1855.

- ↑ 76.0 76.1 Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, p. 326.

- ↑ Australian Encyclopaedia Volume Four ELE-GIB 1983, p. 59.

- ↑ Carboni 1855, pp. 84-85, 94.

- ↑ 79.0 79.1 "TO THE COLONISTS OF VICTORIA". The Argus. Melbourne. 10 April 1855. p. 7 – via Trove.

- ↑ Wenban 1958, p. 25.

- ↑ Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, pp. 226, 424.

- ↑ Historical Studies: Eureka Supplement 1965, p. 36.

- ↑ Australian Dictionary of Biography Vol 5: 1851-1890, K-Q 1974, p. 51.

- ↑ Carboni 1855, p. 51.

- ↑ Carboni 1855, pp. 60-64.

- ↑ 86.0 86.1 Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, p. 57.

- ↑ 87.0 87.1 Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, pp. 57-58.

- ↑ https://www.eurekapedia.org/George_Black

- ↑ Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, p. 452.

- ↑ "Untitled". Ballarat Star. Ballarat. 4 December 1854. p. 2. Retrieved 19 April 2024 – via Trove.

- ↑ Beggs-Sunter 2004, p. 48.

- ↑ 92.0 92.1 Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, p. 340.

- ↑ 93.0 93.1 Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, p. 87.

- ↑ 94.0 94.1 Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, pp. 349-350.

- ↑ 95.0 95.1 95.2 Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, p. 250.

- ↑ Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, p. 506.

- ↑ Lynch 1940, pp. 11-12.

- ↑ Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, pp. 520-522.

- ↑ Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni, pp. 261-622.

- ↑ Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni, p. 261.

- ↑ 101.0 101.1 Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni, p. 137.

- ↑ 102.0 102.1 Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni, pp. 363-364.

- ↑ 103.0 103.1 Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, p. 470.

- ↑ 104.0 104.1 Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, pp. 99-103.

- ↑ 105.0 105.1 Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, p. 329.

- ↑ "Peter Lalor - eurekapedia". www.eurekapedia.org.

- ↑ "Peter Lalor - eurekapedia". www.eurekapedia.org.

Bibliography[edit]

- Australian Dictionary of Biography Vol 5: 1851-1890, K-Q. Carlton: Melbourne University Press. 1974. ISBN 978-0-52-284061-2. Search this book on

- Carboni, Raffaello (1855). The Eureka Stockade: The Consequence of Some Pirates Wanting a Quarterdeck Rebellion. Melbourne: J. P. Atkinson and Co. – via Project Gutenberg. Search this book on

- Corfield, Justin; Wickham, Dorothy; Gervasoni, Clare (2004). The Eureka Encyclopedia. Ballarat: Ballarat Heritage Services. ISBN 978-1-87-647861-2. Search this book on

- Beggs-Sunter, Anne (2004). "Contesting the Flag: the mixed messages of the Eureka Flag". In Mayne, Alan. Eureka: reappraising an Australian Legend. Paper originally presented at Eureka Seminar, University of Melbourne History Department, 1 December 2004. Perth, Australia: Network Books. ISBN 978-1-92-084536-0. Search this book on

- Three Despatches From Sir Charles Hotham. Melbourne: Public Record Office. 1978. ISBN 978-0-72-411706-2. Search this book on

- Withers, William (1999). History of Ballarat and Some Ballarat Reminiscences. Ballarat: Ballarat Heritage Service. ISBN 978-1-87-647878-0. Search this book on

Template:Battle of the Eureka Stockade Template:People of the Eureka Rebellion

This article "List of military leaders in the Eureka Rebellion" is from Wikipedia. The list of its authors can be seen in its historical and/or the page Edithistory:List of military leaders in the Eureka Rebellion. Articles copied from Draft Namespace on Wikipedia could be seen on the Draft Namespace of Wikipedia and not main one.