Anti--Soviet Resistance in Eastern Moldova (MSSR) in 1944-1953

Anti-Soviet resistance in Eastern Moldova (a denomination referring to the Eastern Half of Moldova, a territory between Prut and Nistru Rivers, otherwise known as Bessarabia, and on which the Soviet occupation regime has established the Moldovan Soviet Socialist Republic first in 1940, and then again in 1944) is relatively undiscussed in the international historiography devoted to anti-Soviet and anti-communist resistance in general. Unlike the resistance to the Soviet occupation regime of the Baltic and Ukrainian peoples after the end of World War II, the resistance of the Bessarabian Romanians is virtually unknown. Although lacking the scale of the first ones, the resistance of the Bessarabians was, however, contemporary with the armed resistance towards the occupation regime in other parts of the Western USSR, in fact, forming, together with them, constituent parts of one and the same wider process. T

Historical and historiographic context[edit]

The phenomenon of the post-war popular resistance against the Soviet totalitarian regime is a topic which, if not thoroughly researched, at least then by no means unknown to the international historiography. By the latter, we mean those works which approach the topic and are written in a language of wide international circulation, of which the English language is the most important. By post-war anti-Soviet resistance are meant those various (but mostly armed) forms of non-institutional (yet often organized) popular struggle against the communist regime which took place in the newly annexed Western parts of USSR in the aftermath of the Second World War and through the early ‘50s – the Baltics, Western Ukraine and Belarus, and the Eastern half of Moldova which is most commonly known as Bessarabia. The anti-Soviet resistance within these geographical and chronological frames can logically be considered the last phase of the armed resistance against the regime within.[1] the Soviet state. The previous phases of popular, non-institutional resistance began right after the Communist coup d’état resistance (the war effort of the so-called Whites against the Communists is situated outside the category of a popular resistance) and continued for most of the interwar period with varying intensity, but became acutely problematic for the regime especially during situations of deep crises such as the 1921-1922 famine, the collectivization, and first five-year plan and the 1932-1933 Great Famine it provoked, as well as the Great Terror of 1937-1938. The anti-Communist resistance within the Soviet Union before World War Two was largely apolitical and carried out mostly by peasants, the vast majority of the population[2], and who, at times, could see no option other than to either die in battle against Communists, or in consequence of the latter’s socio-economic experiments and policies of forced modernization, the full brunt of which they bore. From an ideological standpoint, the Communists who, as Marxists, regarded peasants as class enemies due to the latter’s deeply rooted adherence to private property which was a cardinal principle of their way of life, had no problem mercilessly crushing such rebellions during the pre-war phase, and dealing with the phenomenon through various forms of repression, such as mass executions, torture, lengthy prison sentences, deportations of vast segments of rural population to remote and inhospitable regions, by sowing division among peasants, as well as, with the creation of the kolkhozes, by making them fully dependent on the state for their physical survival.

The post-war anti-Soviet armed popular resistance in Western USSR had many of the traits of those rebellions previously defeated by the Communists, as the inhabitants of the newly annexed lands had to be forcibly integrated into the same political and socio-economic system against which people the people of the pre-war USSR have unsuccessfully risen. Their experience had thus to be repeated by the „newcomers”, and had to have the same outcome. Yet in spite of the common traits of the two phases of the phenomenon – such as both being primarily revolts driven by desperation against harsh socio-economic policies and the annihilation of any sort of individual freedom, the post-war resistance among Baltics, Western Ukrainians and Romanians from Eastern Moldova, also bore a distinct cultural and identitarian mark. The people who have lived outside of the Communist reach in the inter-war period, in more liberal societies and were, to various extents, quite distinct from the mass of „Soviet people” (as a result of having previously enjoyed greater freedom than the latter). Thus they were, from a cultural and civilizational standpoint very much unlike the Russians or (Soviet) Ukrainians. The group distinction was reinforced by the fact that they have been annexed as homogenous ethnic and cultural groups, while in the USSR, Stalin, despite himself being Georgian, had, for reasons of political opportunism, adopted as one of the ideological pillars of his dictatorship that extreme form of nationalism, which Lenin branded at the IXth Party Congress of 1920 as the “Great Russian chauvinism”.

While the activity of the partisans in the Baltics and Western Ukraine is a phenomenon relatively known to the international historiography, the same can not be said of the various forms of resistance encountered between 1944 and 1953 in Eastern Moldova, on (roughly) the territory between Prut and Nistru rivers, and which have so far been left outside the scope of books or studies dealing with the post-war Stalinism. Such is the case even among the newest and well-received books on the topic, as Oleg Khlevniuk’s biography of Stalin, which points out the consequences „astounding” consequences of repression – amounting to one million victims - against the guerilla movement in the Baltics and Ukraine[3], but makes no mention of such occurrences in the newly established Moldovan Soviet Socialist Republic (henceforth - MSSR). The causes for this are two-fold. On one hand, the scale of the partisan movement in the Baltics or Western Ukraine was by far more significant and, accordingly, had a greater impact on the culture and history of those societies, and of the world. That happened because, due to various historical reasons, by the middle of 20th century, the Baltic nations and the Western Ukrainians have managed to develop a stronger sense of national and cultural identity, as well as a superior material civilisation that the Romanians in the Eastern Moldova, and thus, having more things to fight for, were more likely than the latter to be willing to put up a fight in defense of their way of life. The population of the Moldovan SSR, was, on the other hand, poorer, less educated, and had a confused sense of national identity, and for these reasons, it was less prone to resort to a national identity based resistance in the face of the Soviet onslaught on its traditional way of life. For this reason, the anti-Soviet resistance in Eastern Moldova could not achieve the level of a national mass-movement characteristic for the Baltics, and was, from a standpoint, more similar to the resistance put up by the Soviet citizens against the regime in the 20’s and 30’s - an often fierce fight triggered by socio-economic consequences of Stalinist policies and repression, and assumed largely by peasants out of desperation and against all odds, while often lacking political or nationalistic principles. That is not to say that occurrences of patriotism, nationalism, or political beliefs as driving forces behind manifestations of the anti-Soviet resistance were uncommon in Moldova, yet such cases were not the backbone of the movement, as opposed to the way things were in the Baltics of Western Ukraine. Yet, even though the phenomenon was less intense in Eastern Moldova than in other parts of the newly occupied Soviet territories, it cannot be reduced to a series of “isolated cases”, and even the assumption that the phenomenon had a “sporadic” character[4] is rather disputable, in the light of the fact that the Soviet occupation authorities themselves recorded hundreds of insurgent groups by mid-1948 alone. The second cause for which the anti-Soviet resistance in Moldovan SSR is not reflected in the international historiography is due to the fact that Romanian historians, either from present-day Moldova or Romania, have not themselves made the effort of bringing this topic to international attention through the publication of the results of their research in languages of international circulation. There is no other way, however, of integrating the knowledge of the forms of post-war resistance against the regime in Eastern Moldova in the general historiography of the anti-Soviet struggle. The only other sources which refer to the topic are those fleeting mentions in works of Soviet origins which, for obvious reasons, did all it could to diminish the proportions of the Moldovan resistance and depict it in most unfavorable colors, as did the official 1962 version of the History of Moldovan Communist Party which branded the resistance fighters as „terrorists” and „bands of kulaks[5] who were attacking kolkhozes and sovkhozes in the districts of Dorchia, Cimișlia, Chișcăreni, Orhei and Strășeni, burning down administrative buildings, robbing peasants, killing presidents of village councils and party and soviet activists”[6], or the 1970 official version of the History of the Moldovan SSR. which stated unequivocally that the food requisition imposed towards the end of World War Two on the Moldovan peasants by the Red Army was in fact a voluntary sacrifice made by the former out of love and gratitude for the latter, and that only “nationalist and kulak elements resisted it” while “conducting anti-Soviet agitation among working peasants, advising them not to fulfill the plan of grain collections, and carrying out terrorist acts against party and Soviet activists”[7].

In the Soviet period. writing s of historians, especially those dealing topics of modern and contemporary history, could be distinguished from the average propagandist only by the degree of the sophistication in which they clothed the paralogisms served to the society[8]. It is obvious that pieces of propaganda as quoted above, both for ethical and professional reasons, can hardly serve as sources for the historical reconstruction of the anti-Soviet movement in Eastern Moldova, and as such, it is the task of the present generation of historians to integrate the knowledge on this topic in its rightful place within the international historiography dealing with the popular, non-institutional anti-Soviet resistance as a whole.Today we have a number of works[9] – books, studies, as well as a number of published documents – upon which we can build the effort to integrate the knowledge of the discussed in the stream of international historiography. One more thing, concerning the documentary sources upon which the vast majority of our knowledge on the topic is built. Although these documents are indeed the primary sources we use in order to understand the phenomenon, it must be said, and we should never forget when working with them, that such documents have been drafted by individuals working within the framework of a system which openly considered those with whose fate we are concerned as its enemies. Thus, those law-enforcement agents, prosecutors, and judges, ministers, etc., on whose reports, memorandums and resolutions the research is based, cannot even for a second be thought of acting impartially when passing judgments upon the resistance fighters whom the system in the framework of which they were working had a priori determined to be (class, or other types of) “enemies”. For them to act in an impartial manner would have meant to act under the framework of an altogether different system, in a different society – perhaps one in which those upon whom the judgments were passed would have not been routinely beaten and tortured to sign false depositions based on which they were later condemned. Thus, when interpreting these sources, the aggressive and hostile language of which is in itself a clear mark of bias, we should proceed with greatest care. One of the two main researchers of the local resistance phenomenon, I. Țurcanu, also warns of a second “dogma”, which, just like the Russian/Soviet patriotism, is a hindrance to the task of depicting a truthful picture of the topic. I. Țurcanu identifies it as “some sort of a strange, loud, inconsistent, and out-of-touch-with reality Romanian nationalism”, while at the same time the author point to Foustel de Coulanges' warning that it is a dangerous error to mistake patriotism, which is a virtue, with history – which is a science[10].

The origins, the premises and the causes of the anti-Soviet resistance in Eastern Moldova[edit]

There are enough grounds to conclude that, even long before the Soviet occupation, the public opinion in Bessarabia was hostile to the Communist regime. Living in a province neighboring with the USSR, its inhabitants were quite aware of the horrors suffered during the interwar period by the soviet citizens as a result of the repressions and policies implemented by the Soviet authorities. One of the results of these misfortunes was that tens of thousands of people took refuge from the Communists in Romania during the interwar period (but especially at the beginning of this period, when the regime's control over foreign borders was not so tight). These people were living witnesses the brutality and cruelty of the Soviet regime, and this phenomenon, together with the incessant incursions, in the 1920s, of the Communist gangs across the Nistru, a process that culminated in the Soviet early hybrid-type provocation at Tatarbunar, created in Eastern Moldova a widespread feeling of fear and hostility towards the totalitarian Soviet regime. This assertion is confirmed by historical documents issued by third party sources, and even by those which might be said did not approve of Bessarabia’s transfer from Russia to Romania. Thus, the American military attaché in Poland, Major Emer Yager, was reporting back home in 1930, after a trip to Bessarabia, that while the local Moldovans were unhappy with the corruption and inefficiency of the local Romanian administration, still they very much preferred it to the regime just across the Nistru River[11]. Similarly, the U.S. ambassador in Bucharest, W.S. Culbertson, informed in 1925 the State Department that the local population of Bessarabia was predominantly anti-Communist and would choose to live under local Romanian administration, despite the latter’s known shortcomings[12]. After the USSR first occupied Bessarabia as a result of the 26-28 June 1940 ultimatum, the US Ambassador, Franklin Mott Gunther was to Washington that „the situation in Bessarabia changed very much for the worse since the administration was transferred to the Communist authorities”, which „countless of Bessarabians being deported to Siberia and the darkest parts of Russia” and tens of thousands forcibly sent to work in the Donbas coal mines. Bessarabia, reported Gunther, became the scene of summary executions, while the number of those imprisoned was several times larger than the capacity of the existing confinment facilities. We know today of around 31000-32000 thousand Romanians arrested and deported in 1941, while another 53000 have been conscripted for forced labor in various parts of the U.S.S.R before the war broke out[13]. The Soviet requisitions and the policy towards the peasants were so draconian, observed the American diplomats, that the latter did not even bother to harvest their crops. Gunther was noting that the Soviet soldiers and officials who arrived in "poverty-schooled" Bessarabia following the occupation have previously been through so much deprivation that they regarded even those articles abandoned by peasants seeking refuge across the Prut River were as "treasures”. The general poverty level in the U.R.S.S. surpassed even that of Bessarabia by so such a large margin that “the poorest families in Chisinau seemed to Soviet soldiers exceptionally rich". Articles of common use, e.g. watches, utensils, crockery, bottles, bottles, but especially footwear, were in the eyes of the Soviets true riches. They confessed to the Bessarabian locals that the shortage in Russia was due to the fact that the Stalinist system was investing all its economic gains in the army because the U.R.S.S. had to be able to protect itself from "capitalist states that were just waiting for the right opportunity to destroy it", but also from "the many enemies inside the country". Because of this, the production of consumer goods for the civil sector was completely ignored. This situation was illustrated by the American Ambassador by the example of the Soviet soldiers and officers who were well equipped, while their wives, even those of officers, walked barefoot or, at best, wore military boots[14].

The ideologically motivated repressions, deportations, and forced requisitions mentioned by F.M. Gunther as occurring in Bessarabia in 1940, became, after 1944, only some of the main causes which determined the emergence of the armed resistance phenomenon among the local population. The fact that the Soviet occupation regime employed brutality and perpetrated arbitrary abuses through its two main branches – the military and public administration, is reflected as early as March 1945 in the latter’s internal documents which state that the breaches of „revolutionary legality” by local public authorities „is creating favorable grounds for the hostile activity of the Moldo-Romanian nationalists against the Soviet Authority”[15]. Numerous abuses against peasants have also been committed by the Red Army personnel, who beat, robbed, and carried out extrajudicial killings of locals, who, as a result, evaded conscription and deserted the Red Army. A 1 January 1945 letter Secretary of the Ungheni District Party Committee, Serghin, to Nikita Salogor, secretary of the CC of the C(b)PM mentioned a series of acts of “robbery, stealing, hooliganism, sometimes murders of peasants” occurring in Ungheni in the last two-three months of 1944, and which were discrediting the Red Army and public administration by provoking the justified indignation of the peasants[16]. Almost four hundreds violent crimes such as murders and abuses committed by the Red Army have been officially registered in Chișinău alone and only during six months of 1945, and the party officials were expressing apprehensions that such events are used by “class enemy elements – kulaks and Moldo-Romanian nationalists, the worst enemies of the Moldovan people, in their anti-Soviet activity”[17]. The Soviet NKVD was not much behind in abuses, as results from a report submitted by Salogor, CC secretary of the C(b)PM, was reporting to Malenkov, CC Secretary of the C(b)PSU, on 15 September 1944, where it is shown that the agency’s actions of arbitrarily occupying residential buildings, as well as Baptist churches and synagogues have caused havoc in Chișinău, and were undermining the Soviet authority and creating grounds for “hostile agitation”[18].

However, such unsanctioned abuses as those listed above were only the very tip of the iceberg, while most of the abuse was, on the contrary authorized and employed systematically by the regime. In the first two and a half years of Soviet occupation, the NKVD has prosecuted and condemned in Moldova 44160 people, as historians note, mainly for ideological grounds such as “nationalism”, or being of “unhealthy” social origins[19]. This phenomenon is better understood in the context of the general situation in the Soviet Union, where, around 7 million sentences were issued either on ideological reasons or to enforce the Stalinist “work discipline” between 1946 and 1952, and where, as of January 1953, well over 5 million people were being held in camps, penal colonies, prisons and“Special settlements” in remote regions[20].

The „social justice” approach of the Soviet authorities based on ideological considerations was designed to sow divisions and divide the society, as, in their drive to control the Moldovan countryside, the Communists often relied on people who were previously the fringe elements of the peasantry. The anectodic evidence still surviving among Moldovan peasant points out to the fact that, when the Communists occupied Moldova, they put in charge of local rural communities drunkards, idlers, or the otherwise most unsuccessful peasants they were able to find in each village, while extolling their destituteness as a virtue. Thus, an anonymous letter from February 1946 to the MSSR Supreme Presidium complained that ”The persecution of those who work honestly has begun with such savagery that, that there are barely left any honest working men not rotting in the prisons of the «heaven». Those who have been the most honest «slaves» of their land are being arrested as kulaks just because they aren't sleeping under fences like drunkards and drones”[21]. Similarly, in July 1956, Maxim Teodor was noting in his journal that the communists put „the biggest thieves and boseaks”[22][23], in charge of administrative duties and bread collections which were starving out the peasants.

The phenomenon of forced requisitions and the devastating famine it provoked in 1946-1947, was one of the three main causes of the Moldovan armed resistance against the Soviet rule. The famine of 1946-1947 was not the first, nor the second great soviet famine. The first such tragic phenomenon took place in 1921-1922, and was caused primarily by the War communism prodrazvyorstka policy of requisitioning the food “surpluses” (izlishki) from the peasants and transfer them to the army and the urban industrial centres so as to be able to sustain the Civil War military effort. The „flexibility” of this policy, which allowed the Communists to abusively confiscate as surpluses all the food (as well as the sowing seeds kept for future harvests[24]) from the countryside, the peasants lacked any incentive to grow bread. This premise, coupled with subsequent drought and poor harvest, escalated into the cause of death for 5 million mainly in Volga region, while million more deaths were avoided only with the help of „Western capitalists”[25], and obliged Lenin to acknowledge the unsustainability of his policies and to introduce the humiliating (for him) NEP.

Stalin’s intensification of class struggle doctrine, which might have been his most significant theoretical contribution to the evolution of Bolshevism[26], proposed that, as the “dictatorship of the proletariat” strengthened, it would inevitably provoke the stiffening of the reaction among the “class enemies”, among whom were the most successful and often hardworking peasants, i.e. the kulaks, which, Stalin predicted, would put up a desperate last fight in order to undermine, overtly and covertly, the government’s critical efforts to build communism, and would, moreover exert influence over the party[27]. In the early thirties, this ideological innovation allowed Stalin to deflect, in front of the worried Communist nomenklatura[28], responsibility for the failures and grave consequences of the industrialization paid for through forced grain collections and collectivization as a means of channeling resources from the countryside, and which starved to death between 5 and 7 million people in Ukraine, Northern Caucasus, Volga Region and Kazakhstan in 1932-1933[29]. In an impressive twist of reality, the blame for this tragedy was laid by the regime on its victims, whom Stalin branded as “saboteurs”, “wreckers” and “idlers”, and who, as he confessed in 1933 to an American diplomat – Colonel Raymond Robins, he believed they deserved to die[30]. The “intensification of class struggle” paralogism, which justified further repression and state terror against the very victims of the Communists, underpinned the way in which of the third catastrophic famine, of 1946-1947, was managed as a crisis by the Soviet leadership. The thesis was most ruthlessly enforced against those peasants who, driven by desperation, dared, as in 1921-1922 and in 1932-1933, to oppose resistance to food requisition causing famine and death, including in the region between Prut and Nistru.

In Eastern Moldova, besides the compulsory food deliveries, the peasants were forced also to obligatory financial contributions, the so-called “state loan”, popularly known as the zaiom, of which 126,6 million of roubles was collected from the population in 1945, and 143 million - in 1946[31]. With regard to food collections (postavka), the planned quantity of food to be collected initially approved in 1944 was subsequently (and in the best stakhanovist tradition), doubled, and then tripled before finally being approved by the CC of the C(b)PM on 14 October 1944. Between 1944 and 1952, the population of Eastern Moldova contributed an amount of 400 million roubles[32] in agricultural deliveries, in the form of ~2,2 million tons of cereals, 0,45 million tons of sunflower seeds, 1,85 million tons of white beet, 8,9 million tons of wool, as well as many hundreds of thousands of tons of other agricultural products[33]. It was common for zealous stakhanovists, eager to fulfill and overfulfill the plans so as to please their bosses in the upper echelons of power, to take away from the peasants much more than the official postavka and which already represented a heavy burden in the post-war and drought circumstances. Those very poor, who simply could not pay the postavka, were arrested sent to labour camps, and we know that of 800 such cases have been recorded in 1946 alone[34]. In the case of very poor peasants, the collectors took whatever food they could find and which was often all the peasants had for subsistence[35]. As these agricultural products were collected, and the food collection plan was over-fulfilled both for 1946 and 1947 (by 28,8%), hundreds of thousands of people died of starvation and famine related diseases[36]. Stalin, meanwhile continued, even under these circumstances and for reasons of foreign policy, the grain exports, exporting 1,7 million tons of grain in 1946 alone. Moreover, Stalin fiercely opposed any proposals (such as coming from Mikoyan and Molotov) to raise the procurement prices from grain in order to raise the living standard of Soviet peasants and offer them meaningful incentives to work and increase productivity[37], and instead was pushing (until the end of his life) for significant increases in the fiscal burdens laid upon the peasantry[38]. But even for those goods for which Moldovan peasants were legally entitled to meager payments, we have evidence that none was received, as for example, we know that in Bălți district alone the peasant alone the peasants were owed 3 million roubles[39]. Forced requisitions not only took away the bread from the peasants, but also any incentive to grow it, and this, coupled with the consequences of the war, resulted in a dramatic five-fold decrease of agricultural output in 1945 compared to 1940[40]. Stalin’s servants in Chișinău, however, pressed on with the food collection plans, and the bread was taken away from the peasants by communists through the means of violence and state terror. As a result, between 150000 and 300000 people died of starvation and various related diseases. By 1 March 1947, there have been recorded 238000 cases of dystrophy[41]; scores of cases of cannibalism have been officially registered. The limited fiscal concessions made by authorities, as well as the belated relief measures which failed due to the bureaucratized and corrupt (and profiteering) character of power structures that were carrying out the distribution of relief, could not avert the catastrophe[42]. The famine led to a significant increase in the anti-Soviet tendencies among the local population. Many peasants sought refuge in the Western half of Moldova[43] (where they were chased and summarily executed by Soviet soldiers and police), while a number decided to oppose arms in hand. According to a report of the Minister of MSSR State Security, Iosif Mordovets, was reporting on 2 December 1946 that “...the anti-Soviet element is obviously activating its hostile undertakings which are assuming a partisan-terrorist nature”[44]. The authorities tried to hide the real dimensions of the famine, but it was impossible. A 14 January anonymous letter addressed to the communist leadership of the Leova district in the southern part of the land stated, “In your congratulations telegrams sent to Moscow you state that the citizens of Bessarabia are handing over everything voluntarily... But this is not so. You took everything and they are starving to death. People are treated like garbage, nay, even garbage is less disposable than people. Flattering, promises, lie and mass arrests are what you do...”[45]. The mitigation measures for the 1946-1947 famine, caused just as the previous two famines - by forced food requisition were, observes Oleg Khlevniuk, the same tried methods employed in 1932-1933, i.e. more repression. Thus, two 4 June 1947 decrees prescribed sentences from five to twenty-five years in a camp for theft, and based on them more than 2 million people were sentenced to prison before Stalin’s death, often parents who were, out of desperation, stealing loaves of bread to feed their emaciated children[46].

The second main cause was the collectivization, which destroyed the peasant’s traditional way of life, and essentially returned him the same kind of slavery abolished in Russia in 1861, with the only difference that the peasants’ fate and freedom belonged now the party of “the working people”, instead of rich and powerful nobility, as before 1861 century. The famine sped up the creation of kholkhozes and sovkhozes, yet even that catastrophe could not determine the majority of the peasants to give up the means of ensuring their economic freedom. Before June 1946 only two kolkhozes have been created, while in July 1947 there were 154 kolkhozes were by 20156 households from the poor category[47] out of a total of 378 thousand individual households[48]. The things didn't evolve much even despite the abuses committed by the over-zealous local communists in their drive to establish the kholkhozes (in 1948 alone 350 officials in MSSR were condemned to prison terms for illegal searches and arrests, corruption, murder, theft, illegal confiscation of private property, etc[49]). Yet once again, what local officials were unable to achieve through unsanctioned forms of oppression, was accomplished through state-organized repression. On the night between 6-7 July 1949, the Soviet authorities rounded up 11293 peasant families (more than 35000) people who we deported to Siberia and Central Asia. The second wave of deportation took place on 1 April 1951 and targeted the Jehovah witnesses – a total number of more than 2600 persons[50]. The deported peasants were the, so as to speak, the elite of the Eastern Moldovan countryside, the most hardworking and successful of their pears, which was precisely why they, as kulaks, have been deported. Their property has been “legally” transferred to the kolkhozes, and often abusively confiscated and looted by higher-ranking local party officials, as it was proven to be the case in the districts of Chișinău, Bălți, Târnova, Râșcani, Vadul lui Vodă, Edineț, Căinari, etc[51]. Besides using the kulaks’ property as a valuable material basis for the establishment of the kolkhozes, the deportation had also the goal of terrifying the rest of the peasants and thus force them into the collective farms. This aim was achieved and, the result, in November 1949 the percentage of collectivized households rose to 80%, and in January 1951, 97% of the Bessarabian peasants have entered kolkhozes[52]. Another tactic by which local political leadership of the occupation authorities sought to herd the peasants into kolkhozes was to increase the postavka and give no tax breaks to individual households,while offering various fiscal incentives for peasants who would join the kolkhozes[53]. Fearing of being branded as kulaks, the peasants entered, or rather were, thereby, coerced to rush into the kolkhozes. But not everyone did. A number of peasants, either escaping deportation[54], or unwilling to enter kolkhozes, chose to oppose the regime by the force of arms and assumed a clandestine way of life.

There were also other causes, yet less important than the main three – the famine caused by requisitions, the collectivization, and the deportations. Among them was the conscription into the Red Army, or the forced labour duty imposed upon the population, the mock elections organized by the communists, and the exhausting lack of pluralism and universal censorship enforced by the authorities. Among such the second category of causes stands, however, the xenophobic policy of the Soviet authorities towards the majority of the local population which ethnically Romanian. The fact that Romania entered the war against the USSR precisely to liberate Bucovina and Bessarabia occupied by the Soviets in 1940 made things a lot worse for the local Romanians. Besides employing physical violence against those would not hide their national identity, the Soviets also did their best to convince the indigenous Romanian men and women, of the fact that they were of different ethnicity (i.e. – Moldovans) that the Romanians living in Romania from which the USSR annexed the eastern part of Moldova. This was done even though the so-called Moldovans were bearing the same names and surnames as the Romanians across the Prut, and although they lived in the villages and towns which, again, bore the same name as various localities in Romania, and in spite of them speaking the same language as the rest of Romanians, and sharing the same cultural tradition and customs. However, since what the Soviets called Moldovan culture is in fact, an organic and indispensable part of the Romanian culture, their task was very difficult and it is beyond any doubt that, despite a lot of damage done, the Stalinists failed to uproot the Romanian national identity of the local population. A major cause for this failure was that the policies which they tried to implement to this end were very confused, incoherent, and unconvincing. Whenever and wherever they looked for examples of „Moldovan culture” the Soviet occupation authorities found only various displays of Romanian spirituality and art, be it old local peasant popular art in its myriad forms, or classical literature of the Romanian writers from Western or Eastern Moldova. Ultimately, the occupation authorities had no other choice but to adopt this Romanian art as Moldovan, and designate it as such, and thus, the classics of the Romanian literature studied in the schools and universities of Romania became also classics of a „foreign”, Moldovan literature. Such confusion is displayed even by the fact that the various repressive agencies of the occupation regime, in their reports, did not know how to refer to local Bessarabians not afraid to display their Romanian ethnic identity. Were they to be designated as Romanian or Moldovan nationalists? In the end, and just to be sure, they were officially branded as „Moldo-Romanian nationalists”[55].

The tactic of crude denationalization was reinforced by a policy of colonization in the framework of which many hundreds of thousands of Russian speakers were brought in Eastern Moldova and where they became a sort of an elite, enjoying privileges such as free housing in the urban areas in which they formed the majority and a privileged status in comparison to that of the local population. In exchange, they were expected to act as a local pillar of the regime. Taking into consideration the fact that, due to their number, it was the Russians who, among all ethnicities of the USSR, endured probably the greatest suffering at the hands of the regime, it was perhaps ironic that many of those Russians who did come here after 1944 faithfully fulfilled the role assigned to the by the party. Victims of their own ignorance, such individuals were granted power positions and privileges, and regarded from above and treated with disdain the local population, marginalizing its language, culture, and customs. The secret police records on the correspondence of „settlers” with their relatives in various parts of the empire reveal the fact that the latter often expressed satisfaction concerning the persecutions of the local population by the occupation authorities. Thus, with regard to the deportations, such letters referred to them as to a positive development: the kulaks were opposed to the Soviet transformations, and „specifically, they hated the new-comers”; „the whole of Moldova was cleansed of the malign elements and people with a certain past”; „In Moldova, the kulaks have been eliminated, which will improve our activity and life”; „Everything will be cheaper now. Many apartments have been freed, and they are being distributed to the inhabitants of the city”; “Between 5 and 7 July, there was a cleansing of Chișinău. Those who cooperated with the Germans and Romanians against the Russians are being deported. Their houses have been given to those citizens who do not have houses”[56]. It would, from every point of view, be unfair, though, to conclude that all newcomers thought and acted in such manner. On the contrary, we have plenty of examples of Russian-speaking individuals who, unflattered by Stalin’s pandering to extreme Russian nationalism, despised the regime and its policies. It is again, from the secret police records, that we know of many instances where the Russian-speaking minority representatives, be they Jews, Ukrainians, Russians, etc., expressed discontent with the regime and sympathy to the local population. Thus, N.A. Shcherbov, lecturer at the Institute for agriculture, was quite aware of the fact that „The difficulties which we’re going through are not the result of the drought and destruction, but due to the fact that the collected production is spent to support the large and parasitic state and party structures. The socialist system is not viable, because the kolkhozes and sovkhozes are a system designed for enslavement. Everything is built through forced labor. The peasants do not want to work since their output is confiscated and fed to the drones”. V.T. Savchenko, builder: “It took me thirty years to realize that the Soviet authority is built upon promises, hopes, lies and intrigues. Exhausting work, miserable pay, unfulfilled promises, phariseeism on the part of the press and governement – this is how we live”; E.I. Penegin: “The peasants have been herded in kolkhozes, this is why they stopped working, and the government, instead of liquidating the kolkhozes is ripping of the peasants, and this is why they are starving”; Robzevich, teacher: “During the Romanian administration, I did not believe the Romanian propaganda on the negative sides of the life in the USSR, yet now we see that the Soviet reality is a horror which surpasses any propaganda”; Golubkina, lecturer: “We live like hungry dogs. Always thinking about food, and wearing rags for clothes. Upon reading the newspapers one can get sick. Every row is a fuss about how good the life is in the USSR, and what famine is abroad”; “Galochkin, senior agronomist, lecturer: “The working man has a good life on paper alone. The constitution says that those work are the ones eating, but the reality is quite the opposite. Look at me, can a specialist with higher education like myself wear such rags?”; Bagovski, engineer and architect: “In the capitalist countries…they struggle to improve the life standard, which is not bad even now. If you gave our worker the American salary, he’d say he has found heaven on earth. If, on the contrary, you’d give the American the amount received by the Russian, he’d run away from such heaven. We have won the war, but what use is it that we have guns and tanks, and that we beat the Germans? During the Romanian administration, I worked as a keeper for a while and was earning more than now, when I am an engineer”, etc., etc., etc[57].

Forms of anti-Soviet resistance in Moldovan SSR[edit]

Desertions from or dodging the Red Army and forced labour conscription[edit]

The non-organized forms of resistance, often passive and non-violent, were the earliest common occurring type of defiance of the local population from Eastern Moldova against the occupation authorities. As the war was still raging on the Eastern Moldovan territory, the peasants attempted to resist, in May 1944, the Soviet plans to relocate 263776 people from the front zone. Unwilling to leave their homes and crops, some peasants engaged in physical altercations with the Red Army which ended in deaths on both sides[58].

Among the most common type of early resistance were draft-dodging and desertion. During the first three months of occupation of 1944 alone, the NKVD had arrested 4321 men who dodged the conscription[59]. In April 1945, the NKVD counted a total number of 15180 deserters and 12942 dodgers from conscription in the Red Army. The Soviet police concluded that the cause of a such mass occurrence was the influence of the anti-Soviet agitation, as well as the warning letters received sent home by the conscripted Bessarabians, in which the latter warned against the cooperation with the regime. A 15 August report of the head of the organizational section of the CC of the C(b)PM of MSSR, states the main reason for the desertion of the local Bessarabians from the Soviet army was „the influence of the agitation conducted by counter-revolutionary elements”[60]. The real, practical, reasons for resistance, were various, among those most prominent being, for example, the fact that they were not allowed to pray, or that they were conscripted only to infantry units[61].

What is quite striking, yet not particularly surprising, is the fact that, in MSSR’s districts East of Nistru, and which in the interwar period were not part of Romania (i.e. already Sovietized) , the desertion and draft evasion was a lot less significant[62]. The men who refused to serve in the Red Army often had no other choice than to seek refuge in the forests and organize themselves so as to be able to survive. Such groups had several members, and in some cases up to dozens of members, usually men from the same villages, often relatives, and their goal was not simply to fend off the attempts by the repressive state organs to catch them, but also to fight the occupation regime and to resist the-Soviet rule, which they thought would be sort-lived. One such group, led by Andrei Zingan and operating in the Florești district, and of which only sporadic mentions have been found, is said to have numbered around 300 members[63]. Such partisans, which we know existed in 1944 in the villages of Sudarca, Carmanovca, Arionești, Rudi of the Otaci district, as well as Cobâlnea, Șeptelici (of Soroca district), Țâpletești and Ruseni (Ocnița district), Telenești (Bălți district), to name just a few. The historians have uncovered from the archives numerous recorded cases deserters organizing attacks and physical annihilation of party activists and loc public officials such as chairmen of village soviets. The NKVD, in its turn, referred to the partisans in their official documents as „bandits” and „terrorists”, seeking to depict them either as common criminals, or as Romanian nationalistic sympathizers of Western imperialists, and, upon catching them, dealt with them ruthlessly[64].

Another form of resistance among the population of Eastern Moldova was the desertion from the various industrial plants and other workplaces whereto the conscripted Bessarabians were forcibly sent to labour. For example, as of 1 January 1947, 6000 local people have “illegally” quit working in the military industry, and, in the coal mines of Voroshilovgrad, 2000 workers forcibly conscripted for labor just in the Cahul district in 1944-1945 were listed as “missing”. In 1947, 36635 Bessarabians were forcibly sent to work in the coal mines and other workplaces of Donetsk, Voroshilovgrad, Stalingrad, Rostov, and in the very same year 6200 of them left their assigned jobs without permission. In January 1948, the MSSR police were searching for 6000 Bessarabians, and thousands of them, once located by the occupation authorities, than have been condemned to prison terms ranging fro 5 to 8 years. Others went into hiding. The phenomenon was so widespread, that the first secretary of the MC(b)P, N. Koval, had no choice but to ask Moscow to allow them to stop searching and prosecuting these people[65].

Resisting food requisition and taxation[edit]

The resistance of the Bessarabian peasants manifested also against the Stalinist system of taxation and compulsory deliveries of agricultural output “surpluses” (izlishki) which were especially draconic in the circumstances of the devastation caused by the war and drought. The communists themselves arbitrarily decided what constituted such “surpluses”, and it often meant not only all the food that the peasants had, but also such that they did not have, or were not even capable to produce, and in these cases, they were liable to be treated as criminals. Yet Stalin would hear nothing of giving the peasants a break and relax the system that he himself has built towards the end of the 1920s and beginning of 1930s precisely to channel for export the resources from the countryside, and thus obtain the finances necessary for his industrialization (and in 1946-1947 for post-war reconstruction) designs. “What is a peasant?” Mikoyan remembers Stalin’s reasoning, “He'll turn over his extra hen and that's an end to it”[66]. Just like in 1932-1933, it did not matter to him that peasants had no extra hen, or that they didn't have a hen at all.

The Bessarabian peasants have unsuccessfully tried to defend the fruits of their labor. Hundreds of letters from the men conscripted in the Red Army back home and asking their families to hide the bread were confiscated by the army censorship July and August 1944. Earlier, we provided a series of figures to illustrate the quantities of food taken from the Bessarabian peasants. Examples are known for the summer of 1944 of peasants taking collectively the decision to attempt to delay as much as possible the Soviet-requested food deliveries in the hope that the tide of war would turn and that the Soviet administration would be forced to leave. Other peasants resorted to desperate measures such as burning their crops, destroying their wagons and inventory, starving or maiming their horses, oxen, cows, and other animals. Even disabled war veterans unable to work were forced to supply fixed quantities of bread, which led to a series of attacks by them on party activists in charge of bread collection in the districts of Nisporeni and Kotovski. Numerous cases of assassinates against party activists tasked with bread collection, members of the village soviets, local NKVD chiefs, etc., have been registered at the beginning of 1945 in the districts of Vadul lui Vodă, Călărași, Comrat, Nisporeni, Kotowski, Chișcăreni, Soroca. In an 11 December 1944 report of Salogor to Malenkov, the former explained that such attacks occurred during the bread collection campaign whereas “anti-Soviet elements carried out terrorist acts against Soviet activists actively engaged in the implementation of the law regarding compulsory bread deliveries to the state” [67]. To various manifestations of disobedience during the food collection campaign, the occupation authorities responded by prosecuting the “perpetrators”. Thus, for the non-compliance to formal requests for compulsory food deliveries, in 1946 almost 1400 people were condemned to prison sentences[68], yet the next year the resistance continued and even assumed new forms, such as burning down of party activists homes, organized attacks against state facilities for grain storage (Zagotzerno) and the deliberate deterioration of the agricultural machinery, such as were the cases in the kolkhozes of “Viața nouă” and “Kotovski” of Romănești district, and also “Pravda”, “Communist” and “Karl Marx” of Cadîr-Lunga and in kolkhozes from the Congaz, the latter two regions being inhabited by Bulgarian and Găgăuz national minorities. The peasants were burning down mills, wheat stores and crops belonging to the kolkhozes, as we know from the cases recorded in the districts of Vertiujeni, Șendreni, Nisporeni , Căușrni, Bender, etc[69]. Numerous attacks, carried out with predilection against Zagotzerno stores where the bread confiscated from the peasants was being kept, took place in the context of the 1946-1947 famine in a number of villages in the districts of Orhei, Bender, Soroca, Comrat, Zgurița, Răspopeni, Cimișlia, Râșcani, Brătușeni, Leova and while the Minister of state security, Mordovets, acknowledged in a 26 April 1946 report that underlying cause of such occurrences was “the ignorance and the careless attitude of the local organs towards the needs of the poor peasants, especially of the families of military servicemen and of those fallen on the war fronts” yet maintained that their principal motive was the “instigation of the anti-Soviet elements taking advantage of the food shortages provoked by the 1945 drought”[70]. Such attacks were sometimes carried out by women, wives and widows of men conscripted in the Red Army driven to such desperate acts by extreme necessity[71]. We know of cases where dozens of women, sometimes accompanied by their children, and forming groups of up of over a hundred persons (as was the case of the 17 March 1986 which took place in the Brânzenii Vechi village of Răspopeni District, or on 30 June 1947 in the v. Orac, d. Leova) who were breaking into Zagotzerno stores and taking tones of cereals. Local public officials, however, preferred to regard these attacks through the lenses of the intensification of class struggle doctrine, and continued to uphold the view that the attacks against cereal stores were not spontaneous acts by starving people, but that, behind such attacks, there stood organized “anti-Soviet elements” who directed them, while those who carried them out were but simple executors of the order of the former[72]. Such primary sources, due to them being ideologically tainted, should be interpreted with care. Yet there seem to have been at least some cases where those who opposed Soviet requisitions did try to conduct organized propaganda work among the peasants with the goal of convincing the latter to collectively resist the occupation authorities’ bread confiscation. For example, a report such “Moldo-Romanian nationalists” being active as of August 1945 in the Soroca district was submitted to the CC of the C(b)PM. Anti-requisition posters have been displayed in d. Otaci in July 1945, and also in July more than 200 peasants have been involved in the distribution of flyers agitating against forced bread collection and kolkhozes in the villages of Corjeuți and Cotiujeni of d. Lipcani. Again in August 1945 flyers containing anti-Soviet slogans and appeals to resist the occupants have been distributed in the districts of Bălți, Glodeni and Fălești. Those caught distributing such materials were prosecuted under the treason penal code article, and condemned to terms of 10 years in prison[73], but the opponents of the regime seemed not discouraged by this, as the 1948 reports of the MSS of Moldovan SSR confirm for that year the circulation of 135 different flyers and other agitation documents of anti-Soviet character, while the Supreme Court set up by the occupation authorities examined, during the first quarter of 1949, 78 criminal files concerning anti-Soviet agitation and other counterrevolutionary offences that occurred during a time when the communists, in accordance with resolutions of the 2nd Congress of the C(b)PM officially commenced the „great battle” for the achievement of the „complete victory or the kolkhoznik organization of the Moldovan village”, victory which, the Communist proclaimed, could not be scored without the complete elimination of those „kulak elements” and „Moldo-Romanian nationalists” who were the „bitter enemies and hangmen of the Moldovan people”[74].

A number of those who opposed the Soviet bread-collection policies from the starving peasants became partisans. Official records 1946-1948 prove that there existed groups of partisans who organized themselves with the specific goal of opposing this taxation policy by attacking fiscal agents, komsomolists, and party activists. Some groups numbered just a few peasants, while other as many as 20, in localities of different regions of Eastern Moldova such as d. Strășeni, d. Drochia, d. Râșcani, d. Târnova, d. Cimișlia, etc. During the first ten months of the year 1946 alone, the occupation authorities recorded 214 acts of “terrorism” and “manifestations of banditism” during which 49 people were killed and 9 wounded, while in the same time-frame the MSSR Ministry of Interior reported it arrested 874 people branded as “bandit and anti-Soviet elements” and liquidated 7 “terrorist groups”, 50 “bandit groups”, and over 150 lone “bandits” and “terrorists”. According to its reports, in the 1966 - mid. 1948 timeframe, the MSSR MoI has been disbanded 217 organized groups comprising a number of 894 guerillas. The vast majority of those arrested were hardworking peasants who had the most to lose as the result of the implementation of the communist policies, as it is indirectly evident from a 12 October 1948 report of the MSSR Minister of Interior, Fyodor Tutushkin, stating that “The economically strongest most hostile anti-Soviet kulak elements, are going underground, acquiring weapons, forming terroristic-banditistic groups, carrying our arson attacks and terrorist acts against local activists. They exercise a certain amount of influence against the backward village elements whom they are attempting to use in their political interests, provoking and instigating them to hostile activity against the Soviet authority”[75]. The forms of the attacks carried out by partisans against representatives of occupation authorities and their collaborators and enablers ranged from mild ones - such as attempts of verbal intimidation or through anonymous letters, to more extreme forms of violence such as beatings, arsons and assassinates. According to the MSSR Ministry of State Security (MSS) reports, in 1947-1948, the agency arrested 41 people for “terrorist intentions”, 45 for partisan activity, and 180 people for anti-Soviet agitation[76]. The fact that the repressive policies against those “kulaks, bandits and other hostile elements” accused of “anti-Soviet agitation and sabotage” did not discourage the resistance is reflected also in the MoI reports from which we know no less than 1000 people have been arrested on such charges by that institution in 1948 alone[77]. Despite the active repression of the insurgents, the MSSR MSS was reporting that, towards the first half of 1949, the activity of those who peasants opposed the occupation regime was gaining pace and becoming reoriented from “threats and intimidations to most intense forms of struggle – such as terror upon local Soviet activists and kolkhoz chairmen”[78]. Still, this form of resistance, fueled by the desperate situation in which the peasants starved out by the regime founds themselves, could not be discouraged by severe, yet targeted repression. For this reasons, the phenomenon of the violent resistance of the Eastern Moldovan population against the occupation regime knew an ascending trend until July 1949, and did not decline until after the Soviet authorities deported in a single night tens of thousands of most prominent (and also most likely to oppose the regime) members of the countryside society. But even after 6-7 July 1949 deportations which were designed to break the resistance of and instill fear in the local peasantry, the trend of violent resistance did not really decline, but has rather plateaued, as illustrated by the MSSR MSS reports showing that during 1949 and the first quarter of 1953, 435 people have been arrested for “counter-revolutionary activity”, while 14 anti-Soviet groups and 110 persons involved in the activity thereof have been liquidated and arrested. Thus, a 1 August 1949 memorandum of the MSSR MSS assessing the results of the deportations concluded that a large share of the Eastern Moldovan population viewed the deportations in a negative light, and among this segment, there were those who were decided to continue to their opposition[79]. The peasants, who, even after 1949 refused to join kolkhozes, were continuously harassed, and cases are recorded of them being driven to suicide, sometimes in extreme form, such as self-immolation[80].

As shown earlier, we know of the existence of hundreds of partisan groups of peasants operating against occupation authorities. Of all social categories, the peasants have proven themselves to be the most successful and astute anti-Soviet opponents. This, of course, can be explained by the fact that they were also the most numerous segment of the population, but also, compared to patriotically minded students or romantic intellectuals, and even to local workers who opposed the regime on political or ideological grounds, they were the ones who acted most decisively taking the fight to the farthest extent in terms of actions and methods employed. One of such peasant groups was Armata Neagră (The Black Army) active in the districts Corneşti, Chişcăreni and Bravicea which was formed in 1949 by men who managed to avoid being deported, and went into hiding in the forest[81]. They were later joined by others, who deserted from the Red Army or avoided being forcibly conscripted to work at industrial plants, or by those who couldn't or wouldn't pay taxes[82]. The group was a classic case of what the occupation authorities branded as “anti-Soviet bandit-terrorist organization”. According to MSS reports, the group consisted of more than 50 men[83]. They were armed, and have carried out a series of attacks against local party and occupation authority representatives, targeting those most involved in food collection and collectivization. By the means of the radio, they were keeping track of the evolution of the international situation, specifically the Cold War Soviet-American tensions. The fact that they were sympathized and supported by locals is confirmed by KGB reports stating that “The intensity of the anti-Soviet activity of the Armata Neagră was possible only due to the vast support which its members received from local anti-Soviet criminal elements”[84]. Such an attitude could not have been manifested by the locals towards common criminals and bandits, as the Soviet authorities claimed the Armata Neagră members to be. During its activity, the group carried out a number of politically and patriotically motivated attacks, against Soviet occupants and their collaborators. Sometimes such attacks took the form beatings and warnings (such as to let children wear crucifixes and not to remove Christian icons from schools). But Armata Neagră also executed its enemies. Among the assassinated were the chairman of the “Socialist Moldova” kolkhoz – Schvartsman, v. Brevicea, or the chairman of the local soviet of village Flămînzeni – Ivanov[85], but also a number of other party and public administration officials installed by the occupation authorities in the villages of Bursuceni, Bobletici, Dereneu, etc., etc[86]. In 1950, the occupation authorities organized manhunts to catch them, during which some were killed in gunfights. Others, upon being caught have been tortured and savagely beaten in order to sign fabricated depositions. The leaders have been sent in front of the firing squads. Dozens of family members and sympathizers have been arrested and sent to prisons and camps in 1950 and 1951[87].

Another remarkable resistance group organized by Bessarabian peasants was Partidul Democrat Agrar – The Agrarian Democratic Party (DAP), active in the Orhei, Răspopeni, Chiperceni and Rezina districts, and led by a number of peasants, among whom was Vasile Odobescu, a Bessarabian peasant who upon for several years in the Romanian army, was, like tens of thousands of other Eastern-Moldovans[88], “repatriated” by the collaborationist Romanian authorities in the USSR in 1944[89]. The case is remarkable because the group viewed itself not just as fighting, but also as a democratic political formation defending the rights of the peasants. The formation’s main goal was the anti-Soviet resistance, through propaganda and agitation among local peasant, as well as by the means of armed struggle directed against the collaborationists and the Soviet occupation authorities[90]. Another remarkable feature is the character of its leader, Vasile Odobescu, who attained legendary status among local peasants[91], being respected by them for such character traits as manifested in the fact that, even after going underground, he would at night-time leave the forest and return to the village to farm his land, until it was taken from his family by the kolkhoz[92]. However, Odobescu was not the founder of the DAP, but rather joined the organization which was created by Simion Zlatan, in 1950, in v. Trifești, d.Rezina. The DAP was a numerous organisation, comprising 25 local organisations in the first half of 1951, which in their turn, had up to 20 members each (as was the case in the villages of Cuizăuca and Trifești); the total number of the fighters remains unknown, but the historians have managed to confirm around one hundred identities[93]. The main forms of activity of the DAP were anti-Soviet propaganda and agitation, but also intimidations and violent attacks against communists and their stooges[94]. The leadership of the DAP, and the majority of its members have been arrested between 1951 and 1953, after the KGB managed to infiltrate informants in the organisation[95]. Odobescu and other leading members were executed.

If Armata Neagră or the DAP are a classic and well-known know example of Bessarabian peasant partisans operating against the Soviet occupation authorities, then the group led by Filimon Bodiu is perhaps the best-known, Bodiu himself attaining during his life-time an outlaw fame in the villages of the regions where he operated; the man self-identified as a “partisan”[96]. The fame was due entirely to the courage, astuteness and extraordinary wit displayed by him during seven years of anti-Soviet insurgency. Arrested for the first time in 1944 for illegal gun possession, Bodiu managed to escape from his captors and went underground. A noticeable particularity is that his family, his wife and two children joined him in illegality[97]. As in the case of other peasants, he was given support by local sympathizing peasants, as is amply evident from MSS reports[98]. In 1947, he managed to gather around himself a group of several fighters, which, according to a report sent on 12 October 1948 by the local Minister of Interior, Tutushkin, to Kruglov, his boss in Moscow, “committed many crimes, terrorist acts and armed robberies”[99]. The Soviet authorities did their best to depict Bodiu as being a hardened criminal which adhered to no principles or values whatsoever, yet this is contradicted by the sympathy common folks had for that man, as acknowledged by the occupants themselves, who admitted that Bodiu could have not escaped them for so many had it not been for “the permanent help and support” he received from other peasants[100]. The authorities identified around 50 supporters of the group[101]. The Soviet claim that Bodiu was but a common criminal is contradicted by the fact that he had drafted a political appeal that he was reading to peasants with whom he often conversed on political and socio-economic topics[102]. Bodiu and his group (which, according to historians’ estimates counting non-combatant active members, was of ten persons), have executed a number of representatives and collaborators of the occupation authorities in the villages of Hirişeni, Mândereşti, Băneşti, Hogineşti, etc. The majority of the actions, however, consisted of various forms of intimidations of party and administration officials, such as beatings, verbal and written threats, etc., by which the partisans aimed at determining the communists to quit, for instance, conducting anti-religious propaganda among in schools[103]. Bodiu himself was killed in a gunfight with troops sent to catch him on 16 November 1950, after being betrayed by a member of his group.

Political and patriotic opposition and anti-Soviet agitation. Attitude of the local population towards the Soviet “electoral” processes in the first years of occupation.[edit]

The various actions which the Bessarabians undertook to express their opposition towards the fake elections organized by the foreign occupation authorities in order to confer upon themselves a semblance of legitimacy, are also relevant to understand the attitude of the local population towards the regime. The 10 February 1946 elections for the Supreme Soviet of USSR, the 21 December local elections, and again in the 12 March 1950 elections for the USSR Supreme Soviet and the 24 December MSSR Supreme Soviet elections, ended (as one would expect it would in a socialist “republic”), with participation and approval rates (of lists of pre-selected candidates) of nearly 100% in all of them. The numbers were also achieved due to the fact that, although the vote was formally a right of the citizen, in practice it was predicated as an obligation, and people would often dare not abstain from its “exercise”. The NKVD, documents, however, show a much different picture characterized by numerous cases of vandalism against visual displays of Soviet propaganda (such as destroying of Stalin’s and Lenin’s portraits), invalidating paper ballots with pro-Romanian and pro-Western inscriptions, stealing electoral lists, electoral agitation meetings being interrupted by discontent citizens party activists and agitators. Numerous cases have been recorded of Bessarabians publicly expressing their disapproval of the mock and anti-democratic character of the elections, while the candidates of the party were branded by voters as “the garbage of our village...drunkards and thieves...incapable of running their own households, not to speak of a village” (v. Todirești, d. Bulboaca)[104]. The occupation authorities branded such manifestations as provocations of those “manipulated by Moldovan nationalists”[105]. As such, Salagor was informing Malenkov towards the end of 1945 that the “nationalist-kulak elements” have intensified their anti-Soviet agitation with the goal of “undermining the trust of the in the elections and for diminishing the political activism of the working masses” and that “repressive measures were being taken against those undertaking anti-Soviet agitation”[106]. In 1947, the Agitation and Propaganda Section of the CC of the C(b)PM was informing the First Secretary of its finding that “during the electoral campaign the burgeois-nationalist and kulak-hostile elements, sectarians and other clerics, taking advantage of the difficulties existing in the republic, have attempted to intensify their criminal and subversive activity” and referred to numerous cases where “the nationalists and kulak Moldovans tried to discredit the representatives by spreading provocative rumors”[107]. The occupation authorities often referred to anti-Soviet activities during the “electoral” period with the terms of “public disorder” and “hooliganism”[108]. 181 files have been examined the MSS Supreme Court set up by the occupation authorities in a time span of less than two years in 1947-1948 has condemned 265 “kulak and nationalist elements” as well as representatives of various cults and churches activating locally[109].

One valuable observation with regard to these documentary sources would be that, even the Stalinists themselves, indirectly though, were admitting that the local population had “difficulties”, but, of course, they would not go so far as to acknowledge that these “difficulties” were the result of their own policies. The fact that so many cases of protest against Soviet mockery of democratic processes have been recorded among a population which, on one hand, was quite poorly educated, and, on the other hand, was known to be rather amorphous from a political perspective; moreover, the fact that such public displays of protest have been recorded during the peak power of the arguably most repressive, despotic and monolithic regime the history has ever known, when Soviet citizens were, as a rule avoiding to speak their mind even in the intimacy of their closes relatives; such observations point out beyond any doubt to a hostility towards the occupation regime so deep and widespread among the local inhabitants of Eastern Moldova that, it was bound to manifest itself defiantly even among harshest oppression and repression. Another form of discontent and resistance virtually unresearched is that of the local Jewish minority in the context of Stalin’s anti-Semitic 1948-1952 campaigns. We have only few but valuable clues and testimonies of its forms[110], and of the suspicions and repressions against those “cosmopolitans”, who, because of growing and state-sanctioned wished to leave the USSR for Israel after 1948[111].

The Bessarabians have set up a number of organized groups which made the focal point of their activity the defense of the local Romanian identity and culture, such as Țăranul Naționalist, Majadahonda[112], Sabia Dreptății, Partidul Libertății, etc. Besides such formations, activated also a number of other groups, more culturally or intellectually oriented in their activity, and that did not assume militant (and, it seems, less clandestine forms), but unsympathetic to the regime. Such were the Fundația regelui Carol, Asociația corpului didactic, Munca și lumina, Asociația Tinerilor Creștini. The latter category was repressed in 1944[113].

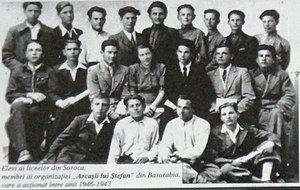

Among the above-mentioned organisations stands out a numerous group organized by pupils, students and teachers of the Northern Soroca and Zgurița districts – Organizația Națională Basarabeană “Arcașii lui Ștefan” - The National Bessarabian Organisation “Stephen’s Archers” (henceforth NBO) in August 1946. This group was distinguished by its displays of serious organization, such as keeping minutes of its sessions. From such documents, we know that the NBO was formed to defend the local population from the Communists aiming to “destroy the Romanian kernel of Bessarabia”[114]. The NBO had its own seal and type of membership card, as well as a hymn and an official patriotic oath which was to be taken by each adhering member. Moreover, the organization had a statute and internal regulations. It was organized in territorial “sections” (comprising several localities each), which, in their turn, comprised local village-level organizations designated as “committees”. NBO had 9 sections “committees” comprising 34 localities[115]. In spite of the fact that its activity program envisaged armed struggle against the occupants, no physical attacks carried out by the NBO against the latter took place, as its leader, Vasile Bătrânac, aimed first at expanding the reach of the group, procuring weapons, and establishing ties with insurgents active in Romania and Western Ukraine (or, at least, that was the official version of the Soviet prosecutors)[116]. By, March-April 1947 when its leadership was arrested, the NBO had around 140 members[117]. Disbanded, its members were prosecuted and condemned to lengthy prison sentences.

A similar fate had another organization of young Romanians, Sabia Dreptăţii (The Sword of Justice, formed by individuals of school age which seem to have had contacts with the NBO. This patriotic organization was active in 1949-1950, in the localities Mândâc, Slănina, Drochia, Şuri, Chetrosu, and Bălţi, and its activity was focused on producing and distributing anti-Soviet flyers, submitting anonymous letters and petition to occupation authorities, and helping peasants to escape the deportations. The members have also sent anonymous letters to writers and journalists collaborating with the occupation authorities, such as those working in the official Writers’ Union. Such letters were full of reproaches, urging the writers to „Stop teaching us that the white is black...that the slavery is freedom, and that the misfortune brought by Stalin upon the people is happiness....If you had a drop of pity for those who suffer under the yoke, you would quit your shameful and despicable jobs. For those who deem themselves human beings cannot watch the poor, naked, and hopeless majority, while proclaiming that it is constituted of happy people”[118]. Upon being arrested, the members of this organisation defiantly affirmed and defended their Romanian national identity even during the brutal interogatories[119]. We know of at least ten members of this organization arrested, tortured, and condemned to sentences up to 25 years in prison between May-November 1950[120].

Partidul Libertăţii (The Freedom Party) was another patriotic organization formed by local Romanian teachers. It was active in 1949 in the central part of Eastern Moldova (districts Chişinău, Cărpineni, and Kotovski). According to MSS reports, it had an “insurrectional, anti-Soviet character” and was formed by “Moldo-Romanian nationalists” opposing the collectivization and the “liquidation of kulaks”, animated by the belief that Eastern Moldova should belong to Romania which they maintained even after being arrested[121]. The members of the organization, despite being dubbed insurgents, were rather idealistically, honest and patriotically minded poor intellectuals, such as teachers working in the rural areas. We know of 29 members of the group arrested between June and August 1950, and its leaders were given death sentences[122]

Another anti-Soviet group established by its members on political grounds was the Democratic Union for Freedom (otherwise known as the Revolutionary Committee for the Liberation of the Peoples of Russia[123]). The case of this organization is particularly interesting since its founders and majority of members were not the usual suspects, i.e. the “Moldo-Romanian nationalists”, but ethnic Russian and Ukrainian workers. The organization was established in the town of Bălţi by Anatolii Miliutin and Nikolai Postol as an underground group whose aim was to overthrow the Soviet regime. The group had its own-built printing press where their political leaflets and appeals (ending with the words Death to communism!) were being printed. The membership of the Union grew to over 30 people[124], and its activity expanded to the proximate district of Floreşti. One of the printed appeals drafted by Miliutin on 15 October 1951 and titled “To officers, soldiers, workers, peasants and intellectuals” read the following: “What did Stalin offer you in 34 years of rule? Slavery, prisons, kolkhozes, and a hungry life. Where is the land, and where is the freedom for which so many tears and so much blood have been shed? Where is equality, where are the rights, and where is the well-being?”[125]. The Union hoped to secretly recruit members of the military, to attack the local labor camps and free the prisoners, and to occupy local military barracks and the airport of the Băţi town, and thus, to start an insurrection that, they imagined, would inspire a general revolt in the USSR. The plans were, however, cut short by the arrest of its members which began in October 1951. The majority of them were Russian and Ukrainian workers. They have been beaten, tortured, and condemned to lengthy prison and hard labor sentences. Miliutin and Postol admitted the charges of anti-Soviet activities, but denied those of treason and terrorism, emphasizing defiantly that anti-communist and anti-Soviet activity cannot qualify as fatherland betrayal[126]. Miliutin was executed.

Resistance on religious and spiritual grounds among cult leaders and followers in the Eastern Moldova[edit]

Perhaps the ultimate cause and explanation for the violent crimes perpetrated by the Communists against tens of millions of individuals belonging to various strata of the societies unfortunate enough to fall under their yoke should be sought in the materialistic character the regimes that they attempted to build. The fact that the Communists seemed to be, for some reason, incapable of looking from a spiritual perspective at the world, to which they denied with a “religious” fanaticism any transcendental reality, could only result in them building a type of society lacking any sort of moral and ethical values which, in their turn, can only rest upon a transcendental understanding of being in general, and cannot be grasped by any analysis of the world undertaken from materialistic or strictly empirical perspective. Therefore, such societies that they built would always treat individuals as a means and never as an end, as opposed to Kant’s categorical imperative which can only be logically and reasonably deducted from a transcendental understanding of reality. This essentially explains the easiness with which the communists carried all the massacres, mass-imprisonment, social and economic experiments, and other crimes that ended and destroyed tens of millions of lives in Russia alone. A similar conclusion seems to have been reached by Richard Pipes, when he keenly emphasized the fact that the failure of Marxist-Communist experiment is explainable only if we understand it as founded upon the “perhaps most damaging idea in the history of human thought” which originated during the Enlightenment, and which proclaimed that individuals were but soulless matter which could be molded into anything they wished[127].