Bone divination

Script error: No such module "Draft topics".

Script error: No such module "AfC topic".

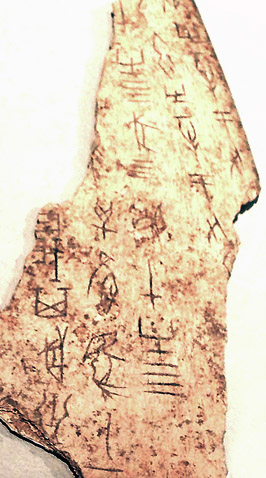

The term Bone Divination (卜辞) refers to the late Shang dynasty practice when shamans carried out divination activities and carved on cow scapula, and turtle shells. It also refers to the compilation of oracle bone characters from the Late Shang period compiled by modern scholars.

The oracle bone script in the divination is far from the modern Chinese characters and is not easy to read and understand. For this reason, ancient Chinese character scholars and archaeologists have worked to decipher the oracle bone inscriptions that were excavated and compiled into a book.

A complete divination rhetoric has four parts: pre-divination rhetoric (narrative rhetoric, narrative rhetoric), destiny rhetoric (chaste rhetoric), occupation rhetoric, and examination rhetoric, and the time of inscription varies. The prescript records the time of divination and the name of the diviner who asked Shangdi, and serves as a narrative, so it is also called narrative and narrative. The fate statement records the specific divination matters and the questions asked of the gods, and is also called the "ching" statement. The "account" records the result of the divination, which is the answer given by the gods according to the analysis of the bone and armor cracks by the shaman. The test word records the results of the divination afterwards and evaluates whether the contents of the divination have been verified.[1]

Name[edit]

Since divination (-mancy) was by heat or fire (pyro-) and most often on plastrons or scapulae, the terms pyromancy, plastromancy[lower-alpha 1] and scapulimancy are often used for this process.

Materials[edit]

The oracle bones are mostly tortoise plastrons (ventral or belly shells, probably female[lower-alpha 2]) and ox scapulae (shoulder blades), although some are the carapace (dorsal or back shells) of tortoises, and a few are ox rib bones,[lower-alpha 3] scapulae of sheep, boars, horses and deer, and some other animal bones.[lower-alpha 4] The skulls of deer, oxen and humans have also been found with inscriptions on them,[lower-alpha 5] although these are very rare and appear to have been inscribed for record keeping or practice rather than for actual divination;[3][lower-alpha 6] in one case, inscribed deer antlers were reported, but Keightley (1978) reports that they are fake.[4][lower-alpha 7] Neolithic diviners in China had long been heating the bones of deer, sheep, pigs and cattle for similar purposes; evidence for this in Liaoning has been found dating to the late fourth millennium BCE.[5] However, over time, the use of ox bones increased, and use of tortoise shells does not appear until early Shang culture. The earliest tortoise shells found that had been prepared for divinatory use (i.e., with chiseled pits) date to the earliest Shang stratum at Erligang (Zhengzhou, Henan).[6] By the end of the Erligang, the plastrons were numerous,[6] and at Anyang, scapulae and plastrons were used in roughly equal numbers.[7] Due to the use of these shells in addition to bones, early references to the oracle bone script often used the term "shell and bone script", but since tortoise shells are actually a bony material, the more concise term "oracle bones" is applied to them as well.

The bones or shells were first sourced and then prepared for use. Their sourcing is significant because some of them (especially many of the shells) are believed to have been presented as tribute to the Shang, which is valuable information about diplomatic relations of the time. We know this because notations were often made on them recording their provenance (e.g., tribute of how many shells from where and on what date). For example, one notation records that "Què (雀) sent 250 (tortoise shells)", identifying this as, perhaps, a statelet within the Shang sphere of influence.[8][9][lower-alpha 8] These notations were generally made on the back of the shell's bridge (called bridge notations), the lower carapace, or the xiphiplastron (tail edge). Some shells may have been from locally raised tortoises, however.[lower-alpha 9] Scapula notations were near the socket or a lower edge. Some of these notations were not carved after being written with a brush, proving (along with other evidence) the use of the writing brush in Shang times. Scapulae are assumed to have generally come from the Shang's own livestock, perhaps those used in ritual sacrifice, although there are records of cattle sent as tribute as well, including some recorded via marginal notations.[11]

Preparation[edit]

The bones or shells were cleaned of meat and then prepared by sawing, scraping, smoothing and even polishing to create convenient, flat surfaces.[10][12][lower-alpha 10] The predominance of scapulae and later of plastrons is also thought to be related to their convenience as large, flat surfaces needing minimal preparation. There is also speculation that only female tortoise shells were used, as these are significantly less concave.[8] Pits or hollows were then drilled or chiseled partway through the bone or shell in orderly series. At least one such drill has been unearthed at Erligang, exactly matching the pits in size and shape.[13] The shape of these pits evolved over time and is an important indicator for dating the oracle bones within various sub-periods in the Shang dynasty. The shape and depth also helped determine the nature of the crack that would appear. The number of pits per bone or shell varied widely.

Cracking and interpretation[edit]

Divinations were typically carried out for the Shang kings in the presence of a diviner. A very few oracle bones were used in divination by other members of the royal family or nobles close to the king. By the latest periods, the Shang kings took over the role of diviner personally.[14]

During a divination session, the shell or bone was anointed with blood,[15] and in an inscription section called the "preface", the date was recorded using the Heavenly Stems and Earthly Branches, and the diviner name was noted. Next, the topic of divination (called the "charge") was posed,[lower-alpha 11] such as whether a particular ancestor was causing a king's toothache. The divination charges were often directed at ancestors, whom the ancient Chinese revered and worshiped, as well as natural powers and Dì (帝), the highest god in the Shang society. A wide variety of topics were asked, essentially anything of concern to the royal house of Shang, from illness, birth and death, to weather, warfare, agriculture, tribute and so on.[16] One of the most common topics was whether performing rituals in a certain manner would be satisfactory.[lower-alpha 12]

An intense heat source[lower-alpha 13] was then inserted in a pit until it cracked. Due to the shape of the pit, the front side of the bone cracked in a rough 卜 shape. The character 卜 (pinyin: bǔ or pǔ; Old Chinese: *puk; "to divine") may be a pictogram of such a crack; the reading of the character may also be an onomatopoeia for the cracking. A number of cracks were typically made in one session, sometimes on more than one bone, and these were typically numbered. The diviner in charge of the ceremony read the cracks to learn the answer to the divination. How exactly the cracks were interpreted is not known. The topic of divination was raised multiple times, and often in different ways, such as in the negative, or by changing the date being divined about. One oracle bone might be used for one session or for many,[lower-alpha 14] and one session could be recorded on a number of bones. The divined answer was sometimes then marked either "auspicious" or "inauspicious", and the king occasionally added a "prognostication", his reading on the nature of the omen.[18] On very rare occasions, the actual outcome was later added to the bone in what is known as a "verification".[18] A complete record of all the above elements is rare; most bones contain just the date, diviner and topic of divination,[18] and many remained uninscribed after the divination.[17]

The uninscribed divination is thought to have been brush-written with ink or cinnabar on the oracle bones or accompanying documents, as a few of the oracle bones found still bear their brush-written divinations without carving,[lower-alpha 15] while some have been found partially carved. After use, shells and bones used ritually were buried in separate pits (some for shells only; others for scapulae only),[lower-alpha 16] in groups of up to hundreds or even thousands (one pit unearthed in 1936 contained over 17,000 pieces along with a human skeleton).[19]

Changes in the nature of divination[edit]

The targets and purposes of divination changed over time. In the reign of Wu Ding diviners were likely to ask the powers or ancestors about things like the weather, success in battle, or building settlements. Offerings were promised if they would help with earthly affairs.

Crack-making on jiazi (day 1) Zheng divined “In praying for harvest to the Sun (we) will cleave ten dappled cows and pledge one hundred dappled cows.”

Keightley explains that this divination is unique in being addressed to the Sun, but typical in that 10 cattle are being offered, with 100 more to follow if the harvest is good.[20] Later divinations were more likely to be perfunctory, optimistic, made by the king himself, addressed to his ancestors, on a regular cycle, and unlikely to ask the ancestors to do anything. Keighley suggests that this reflects a change in ideas about what the powers and ancestors could do and the extent to which the living could influence them. [21]

Bibliography[edit]

- 陳夢家:《殷虛卜辭綜述》(北京:中華書局,2004)。

- 刘学顺:〈贞旬卜辞与殷王朝的年代 (页面存档备份,存于)〉。

- Keightley, David N. (1978a). Sources of Shang history : the oracle-bone inscriptions of Bronze Age China. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-02969-0. Search this book on

See Also[edit]

- Divination

- Oracle bone script

- Oraculology

External Links[edit]

- 中央研究院國家寶藏館-帶刻辭鹿頭骨中央研究院數位典藏資源網

Sources[edit]

Footnotes[edit]

- ↑ According to Keightley 1978a, p. 5, citing Yang Junshi 1963, the term plastromancy (from plastron + Greek μαντεία, "divination") was coined by Li Ji.

- ↑ Keightley 1978a, p. 9 – the female shells are smoother, flatter and of more uniform thickness, facilitating pyromantic use.

- ↑ According to Chou 1976, p. 7, only four rib bones have been found.

- ↑ such as ox humerus or astragalus (ankle bone).[2]

- ↑ Xu 2002, p. 34 shows a large, clear photograph of a piece of inscribed human skull in the collection of the Institute of History and Philology at the Academia Sinica, Taiwan, presumably belonging to an enemy of the Shang.

- ↑ There appears to be some confusion in published reports between inscribed bones in general, and bones that have actually been heated and cracked for use in divination.

- ↑ Xu 2002, p. 35 does show an inscribed deer skull, thought to have been killed by a Shang king during a hunt.

- ↑ Some cattle scapulae were also tribute.[10]

- ↑ Keightley 1978a, p. 12 mentions reports of Xiǎotún villagers finding hundreds of shells of all sizes, implying live tending or breeding of the turtles onsite.

- ↑ Chou 1976, p. 12 notes that evidence of sawing is present on some oracle bones, and that the saws were likely of bronze, although none have ever been found.

- ↑ There is scholarly debate about whether the topic was posed as a question or not; Keightley prefers the term "charge", since grammatical questions were often not involved.

- ↑ For a fuller overview of the topics of divination and what can be gleaned from them about the Shang and their environment, see Keightley 2000.

- ↑ The nature of this heat source is still a matter of debate.

- ↑ Most full (non-fragmentary) oracle bones bear multiple inscriptions, the longest of which are around 90 characters long.[17]

- ↑ Qiu 2000, p. 60 mentions that some were written with a brush and either ink or cinnabar, but not carved.

- ↑ Those that were for practice or records were buried in common rubbish pits.[19]

References[edit]

- ↑ 郭沫若 (1933年). 《卜辞通纂》 (in 中文). Check date values in:

|year=(help) Search this book on

- ↑ Chou 1976, p. 1.

- ↑ Keightley 1978a, p. 7.

- ↑ Keightley 1978a, p. 7, note 21.

- ↑ Keightley 1978a, p. 3.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Keightley 1978a, p. 8.

- ↑ Keightley 1978a, p. 10.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Keightley 1978a, p. 9.

- ↑ Xu 2002, p. 22.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Xu 2002, p. 24.

- ↑ Keightley 1978a, p. 11.

- ↑ Keightley 1978a, pp. 13–14.

- ↑ Keightley 1978a, p. 18.

- ↑ Qiu 2000, p. 61.

- ↑ Xu 2002, p. 28, citing the Rites of Zhou.

- ↑ Keightley 1978a, pp. 33–35.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Qiu 2000, p. 62.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Xu 2002, p. 30.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Xu 2002, p. 32.

- ↑ David N. Keightley “The Making of the Ancestors: Late Shang Religion and its Legacy” in Keightley, David N. These Bones Shall Rise Again: Selected Writings on Early China.. Albany, NY: State Univ of New York Pr, 2014. p.161

- ↑ David N. Keightley “Late Shang Divination: The Magico-Religious Legacy” in Keightley, David N. These Bones Shall Rise Again: Selected Writings on Early China.. Albany, NY: State Univ of New York Pr, 2014 p.108, David N. Keightley “The Shang: China’s First Historical Dynasty” in Loewe, Michael, and Edward L. Shaughnessy. The Cambridge History of Ancient China: From the Origins of Civilization to 221 BC. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999. p.243-5

This article "Bone divination" is from Wikipedia. The list of its authors can be seen in its historical and/or the page Edithistory:Bone divination. Articles copied from Draft Namespace on Wikipedia could be seen on the Draft Namespace of Wikipedia and not main one.