Partition and secession in California

California, the most populous state in the United States and third largest in area after Alaska and Texas, has been the subject of more than 220 proposals to divide it into multiple states since its admission to the United States in 1850,[1] including at least 27 significant proposals in the first 150 years of statehood.[2] In addition, there have been some calls for the secession of multiple states or large regions in the American West (such as the proposal of Cascadia) which often include parts of Northern California.

One-third of California residents in a 2016–2017 poll supported peacefully seceding from the United States, up from 20% in 2014.[3] A new poll taken in 2018 found that only 14% of voters supported peacefully seceding from the United States, down from 33% in 2017. [4]

Prior California partitions[edit]

California was partitioned in its past. What under Spanish rule was called the Province of the Californias (1768–1804) was divided into Alta California (Upper California) and Baja California (Lower California) in 1804 at the line separating the Franciscan missions in the north from the Dominican missions in the south.

After the Mexican–American War, Alta California was admitted to the United States as the present-day State of California. Baja California remained under Mexican rule.

In 1888, under the government of President Porfirio Díaz, Baja California became a federally administered territory called the North Territory of Baja California ("north territory" because it was the northernmost territory in the Republic of Mexico). In 1952, the northern portion of this territory (above 28°N) became the 29th state of Mexico, called Baja California; the sparsely populated southern portion remained a federally administered territory. In 1974, it became the 31st state of Mexico, admitted as Baja California Sur.

History of partition movements[edit]

Pre-statehood[edit]

The territory that became the present state of California was acquired by the U.S. as a result of the Mexican–American War and subsequent 1848 Mexican Cession. After the war, a confrontation erupted between the slave states of the South and the free states of the North regarding the status of these acquired territories. Among the disputes, the South wanted to extend the Missouri Compromise line (36°30' parallel north), and thus slave territory, west to Southern California and to the Pacific coast, while the North did not.[5]

Starting in late 1848, Americans and foreigners of many different countries rushed into California for the California Gold Rush, exponentially increasing the population. In response to growing demand for a better more representative government, a Constitutional Convention was held in 1849. The delegates there unanimously outlawed slavery, and had no interest in extending the Missouri Compromise Line through California; the lightly populated southern half never had slavery and was heavily Hispanic.[6] They thus applied for statehood in the current boundaries. As part of the Compromise of 1850, the South reluctantly acceded to having California be a free state, and it officially became the 31st state in the union on September 9, 1850.

Post-statehood[edit]

Southern California attempted three times in the 1850s to achieve a separate statehood or territorial status from Northern California.

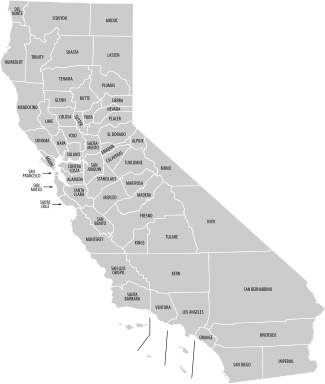

- In 1855, the California State Assembly passed a plan to trisect the state.[7] All of the southern counties as far north as Monterey, Merced, and part of Mariposa, then sparsely populated but today containing about two-thirds of California's total population, would become the State of Colorado (the name Colorado was later adopted for another territory established in 1861), and the northern counties of Del Norte, Siskiyou, Modoc, Humboldt, Trinity, Shasta, Lassen, Tehama, Plumas, and portions of Butte, Colusa (which included what is now Glenn County), and Mendocino, a region which today has a population of little more than half a million, would become the State of Shasta. The primary reason was the size of the state's territory. At the time, the representation in Congress was too small for such a large territory, it seemed too extensive for one government, and the state capital was too inaccessible because of the distances to Southern California and various other areas. The bill eventually died in the Senate as it became very low priority compared to other pressing political matters.[7]

- In 1859, the legislature and governor approved the Pico Act (named after the bill's sponsor Andrés Pico, state senator from Southern California) splitting off the region south of the 36th parallel north as the Territory of Colorado.[8][9][10] The primary reason cited was the difference in both culture and geography between Northern and Southern California. It was signed by the State governor John B. Weller, approved overwhelmingly by voters in the proposed Territory of Colorado, and sent to Washington, D.C. with a strong advocate in Senator Milton Latham. However the secession crisis and American Civil War following the election of Lincoln in 1860 prevented the proposal from ever coming to a vote.[7][11][12][13]

- In the late 19th century, there was serious talk in Sacramento of splitting the state in two at the Tehachapi Mountains because of the difficulty of transportation across the rugged range. The discussion ended when it was determined that building a highway over the mountains was feasible; this road later became the Ridge Route, which today is Interstate 5 over Tejon Pass.

20th century[edit]

- Since the mid-19th century, the mountainous region of northern California and parts of southwestern Oregon have been proposed as a separate state. In 1941, some counties in the area ceremonially seceded, one day a week, from their respective states as the State of Jefferson. This movement disappeared after America's entry into World War II, but the notion has been rekindled in recent years.[14]

- The California State Senate voted on June 4, 1965, to divide California into two states, with the Tehachapi Mountains as the boundary. Sponsored by State Senator Richard J. Dolwig (R-San Mateo), the resolution proposed to separate the 7 southern counties, with a majority of the state's population, from the 51 other counties, and passed 27-12. To be effective, the amendment would have needed approval by the State Assembly, by California voters, and by the United States Congress. As expected by Dolwig, the proposal did not get out of committee in the Assembly.[15]

- In 1992, State Assemblyman Stan Statham sponsored a bill to allow a referendum in each county on a partition into three new states: North, Central, and South California. The proposal passed in the State Assembly but died in the State Senate.[16]

21st century[edit]

-

2009: Martin Hutchinson's proposalSan Diego/ Orange County/ Inland EmpireGreater Los AngelesSan Francisco/ Sacramento/ Santa Cruz/ Silicon ValleyNorthern/Central Valley

-

2009: Bill Maze's proposal

-

2011: Jeff Stone's proposalSouth California

-

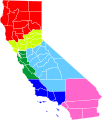

2013: Map of the Six CaliforniasJeffersonNorth CaliforniaSilicon ValleyCentral CaliforniaWest CaliforniaSouth California

-

2018: Paul Preston's proposalNew California

- In the wake of the 2003 gubernatorial recall, Tim Holt and Martin Hutchinson proposed in separate newspaper op-eds that the state should split into as many as four new states, dividing distinct geographically and politically defined regions as the Bay Area, North Coast, and Central Valley, as well as the historic Shasta/Jefferson region, into their own states.[17][18]

- In early 2009, former State Assemblyman Bill Maze began lobbying to split thirteen coastal counties, which usually vote Democratic, into a separate state to be known as either "Coastal California" or "Western California." Maze's primary reason for wanting to split the state was because of how "conservatives don't have a voice" and how Los Angeles and San Francisco "control the state." The counties that would make up the new state would be Marin, Contra Costa, Alameda, San Francisco, San Mateo, Santa Clara, Santa Cruz, San Benito, Monterey, San Luis Obispo, Santa Barbara, Ventura, and Los Angeles Counties. It has also been proposed that the state be split in two simply at the straight divide of the 120th meridian west, much like its border with the state of Nevada.[19]

- In June 2011, Republican Riverside County Supervisor Jeff Stone called for Riverside, Imperial, San Diego, Orange, San Bernardino, Kings, Kern, Fresno, Tulare, Inyo, Madera, Mariposa and Mono counties (see map, highlighted in red) to separate from California to form the new state of South California. Officials in Sacramento responded derisively, with governor Jerry Brown's spokesperson saying "A secessionist movement? What is this, 1860? It's a supremely ridiculous waste of everybody's time."[20] and fellow supervisor Bob Buster calling Stone "crazy," suggesting "Stone has gotten too much sun recently."[21]

- In September 2013, county supervisors in both Siskiyou County and Modoc County voted to join a bid to separate and create a new "State of Jefferson".[14] Mark Baird, spokesperson for the Jefferson Declaration Committee, is reported to have said the group hopes to obtain commitments from as many as a dozen counties, after which they will ask the state legislature to permit formation of the new state based on Article 4, Section 3 of the US Constitution. In January 2014, supervisors in Glenn County voted in favor of separation,[22] and in April 2014, Yuba County supervisors voted to become the fourth California county to join the movement.[23] On June 3, 2014, residents in Del Norte County voted against separation by 58 percent to 42 percent,[24] however, voters in Tehama County supported a separation initiative by 57 percent to 43 percent.[25] On July 22, 2014, Sutter County voted 5-0 to join the State of Jefferson.[26]

- Six Californias: On December 19, 2013, venture capitalist Tim Draper submitted a six-page proposal[27][28] to the California Attorney General to split California into six new states, citing improved representation, governance, and competition between industries.[29] On February 19, 2014, Secretary of State Debra Bowen approved the proposal allowing supporters to start collecting signatures in order to qualify the petition for a ballot. A total of 807,615 registered voters were needed by July 18, 2014 for the proposal to appear on the ballot.[30] On July 14, the petition organizer announced that the proposal received enough signatures to be placed on the ballot in two years,[31] however, it was determined that only about two thirds were valid and the petition fell short of qualifying for the November 2016 ballot.[32]

- New California: On January 16th, 2018, the 501(c)(4) organization New California, organized by conservative radio talk show host Paul Preston, published its proposed state's Declaration of Independence. They cited the split for being the 48th out of 50 for business climate and also cited high taxes and supposed failure to follow the state and federal constitutions. New California would include the rural counties that make up most of the state's area north, south and east of the more heavily populated coastal areas between counties around San Francisco and Los Angeles.[33] New California would also include the urban areas of Contra Costa County, Orange County, and San Diego County, bringing the population to around 20 million.[33][34]

- In April 2018, the Cal3 organization announced it had more than 600,000 signatures to place an initiative on the November 2018 ballot proposing that California should be split into three separate states.[35] The signatures must be verified before the proposal qualifies for the ballot.[36]

Secession[edit]

Ecotopia[edit]

Writer Ernest Callenbach wrote a 1975 novel, entitled Ecotopia, in which he proposed a full-blown secession of Northern California, Oregon, and Washington from the United States in order to focus upon environmentally friendly living and culture. He later abandoned the idea stating: "We are now fatally interconnected, in climate change, ocean impoverishment, agricultural soil loss, etc. etc. etc."[37]

Cascadia[edit]

While mostly consisting of Washington, Oregon, Idaho and British Columbia in Canada, proposals for an independent Cascadia often include portions of northern California.

California National Party[edit]

Founded in 2014, California National Party (CNP) is a political party advocating a progressive platform. The CNP is running candidates throughout California at the state and local level, beginning with the 2018 election cycle. The CNP also seeks, as a long-term goal, the secession of California from the United States by legal and peaceful means.

Calexit[edit]

In the wake of Republican nominee Donald Trump winning the 2016 presidential election, a fringe movement organized by Yes California, referred to as "Calexit" - a term inspired by the successful 2016 Brexit referendum, arose in a bid to gather the 585,407 signatures necessary to place a secessionist question on the 2018 ballot.[38]

See also[edit]

- Secession in New York

- Texas divisionism

- List of U.S. state partition proposals

- California National Party

References[edit]

- ↑ Daniel B. Wood (July 12, 2011). "51st state? Small step forward for long-shot 'South California' plan". The Christian Science Monitor. Yahoo! Inc. Retrieved July 18, 2011.

- ↑ "History of Proposals to Divide California". Three Californias. Retrieved 2008-07-11.

- ↑ Willon, Phil. "Support for California secession is up, one poll says". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- ↑ http://www.surveyusa.com/client/PollReport.aspx?g=8e80b193-ad6a-40b3-9fdf-736154c17fea

- ↑ Mark J. Stegmaier (1996). Texas, New Mexico, and the compromise of 1850: boundary dispute & sectional conflict. p. 177. Search this book on

- ↑ Ellison, William Henry (1950). A Self-governing Dominion: California, 1849-1860. University of California Press. Search this book on

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Ellison, William Henry (October 1913). "The Movement for State Division in California, 1849-1860". The Southwestern Historical Quarterly. 12 (2): 101–139. JSTOR 30234593.

- ↑ Leo, Michael Di; Smith, Eleanor (June 1, 1983). Two Californias: The Myths And Realities Of A State Divided Against Itself. Island Press. ISBN 9780933280168. Search this book on

- ↑ California, Historical Society of Southern; California, Los Angeles County Pioneers of Southern (1901). The Quarterly. Retrieved November 10, 2016. Search this book on

- ↑ Sandefur, Timothy (April 2009). "Hindsight". Callawyer.com. Retrieved November 10, 2016.

- ↑ Leo, Michael Di; Smith, Eleanor (1983). Two Californias: The Myths And Realities Of A State Divided Against Itself. Island Press. pp. 9–30. ISBN 9780933280168. Search this book on

- ↑ J. M. Guinn, HOW CALIFORNIA ESCAPED STATE DIVISION, The Quarterly, Volumes 5-6 By Historical Society of Southern California, Los Angeles County Pioneers of Southern California. Retrieved October 4, 2014. Search this book on

- ↑ "Civil War: How Southern California Tried to Split from Northern California". KCET. Retrieved October 4, 2014.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Romney, Lee (September 25, 2013). "Modoc becomes second California county to back secession drive". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved June 28, 2014.

- ↑ "California Senate acts to cut state in two in districting fight". Syracuse Herald-Journal. June 5, 1965. p. 1.

- ↑ Evans, JIm (January 3, 2002). "Upstate, downstate". Sacramento News & Review. Retrieved July 7, 2008.

- ↑ Holt, Tim (2003-08-17). "A modest proposal: downsize California!". The San Francisco Chronicle.

- ↑ Hutchinson, Martin (2009-05-21). "Califournia Breakup?". Thomas Reuters. Archived from the original on 8 July 2011. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ↑ "Home Page". 23 October 2011. Archived from the original on 23 October 2011.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- ↑ "Could 'South California' become the 51st US state?". Daily Telegraph. 2011-07-11.

- ↑ "Official Calls For Riverside, 12 Other Counties To Secede From California". KCBS. July 1, 2011.

- ↑ Romney, Lee (January 23, 2014). "Glenn County is third in Calif. to back breakaway State of Jefferson". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved June 28, 2014.

- ↑ Janes, Nick (April 16, 2014). "Yuba County Joins State Of Jefferson Movement To Split California". CBS13 Sacramento. Retrieved June 28, 2014.

- ↑ June 3, 2014 Primary Election - County of Del Norte Archived June 8, 2014, at the Wayback Machine;

- ↑ Wilson, Reid (June 4, 2014). "One California county votes to separate, two counties vote to stick around". The Washington Post. Retrieved June 28, 2014.

- ↑ Smith, Steven (July 22, 2014). "Sutter County Board of Supervisors Summary of July 22, 2014". Sutter County. Retrieved July 22, 2014.

- ↑ Draper, Timothy. "Six Californias". Initiative Measure Submitted Directly to Voters. Retrieved 20 December 2013.

- ↑ Draper, Timothy. "Six Californias". Website. Retrieved 20 December 2013.

- ↑ Draper, Timothy. "Tim Draper Wants To Split California Into Pieces And Turn Silicon Valley Into Its Own State". TechCrunch. Retrieved 20 December 2013.

- ↑ Fields, Kayle. "Petition to Split California Into Six States Gets Green Light". abcnews.go.com. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- ↑ Chaussee, Jennifer (July 14, 2014). "Billionaire's breakup plan would chop California into six states". Chicago Tribune. Reuter. Retrieved July 15, 2014.

- ↑ Six Californias initiative fails, sacbee.com.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 "New California Declares Independence From Rest Of State". cbslocal.com. 15 January 2018.

- ↑ Betz, Bradford (January 17, 2018). "'New California' movement seeks to divide the Golden State in half". Fox News. Retrieved January 19, 2018.

- ↑ ""CAL 3" Initiative to Partition California Reaches Unprecedented Milestone" (PDF) (Press release). Cal3. 11 April 2018. Retrieved 19 April 2018.

- ↑ Ting, Eric (13 April 2018). "Plan to split California into 3 states may qualify for ballot". SFGate. Hearst.

- ↑ Matt Sledge (July 14, 2011). "San Francisco Secession: Could It Create 'Ecotopia'?". Huffington Post.

- ↑ ‘California is a nation, not a state’: A fringe movement wants a break from the U.S. at the Wayback Machine (archived February 20, 2017)

This article "Partition and secession in California" is from Wikipedia. The list of its authors can be seen in its historical and/or the page Edithistory:Partition and secession in California. Articles copied from Draft Namespace on Wikipedia could be seen on the Draft Namespace of Wikipedia and not main one.

|

This page exists already on Wikipedia. |