Thomas Stanley (clergyman)

Resubmitting with I hope properly formatted references so will be approved. Simon Daniell.

Thomas Stanley - Clergyman, Eyam, Derbyshire (c1600-1670): A historically important clergyman[1]

Unfortunately there is no known picture of Thomas Stanley.[2]

When history recounts the story of the Plague at Eyam (1665-6) [3] [4] William Mompesson is hailed as the hero, but the absolutely crucial role of Thomas Stanley is often missed. [5] These men could not have been more opposite in their churchmanship but whatever suspicions one may have held of the other it is clear that they were able to work in harmony together in the crisis years as they both put aside their differences for the good of their flock and ministered to the dying and the bereaved with no thought for their own safety. This is an astonishing part of the plague story. The surprising thing is that two such people worked together at all, considering Stanley had lost his living, his home, his parish and his parishioners to Mompesson and obviously had very different religious views but they did. Stanley’s Puritan beliefs contrasted strongly with Mompesson’s faith in the unified Anglican Church. Stanley had resigned over the introduction of The Book of Common Prayer and Mompesson was appointed rector, but Stanley also helped with the writing of wills.

“I am sure Thomas Stanley tried very hard to live strictly according to the tenets of 17th century Puritanism: I am equally sure he really did a very much better thing. He did which ought to assure him a high place on the Derbyshire roll of honour.” Letter to Newspaper by Chas W Wigfell, Alton, Stoke-on-Trent[6]

These were very difficult times in England following the Civil War 1642-51, the execution of Charles I in 1649, the battle of Marston Moor 1644 in which Eyam men had taken part, the restoration of Charles II in 1660 and the Book of Common Prayer published in 1662. Before Mompesson came to Eyam Shorland Adams had been rector (1630-44) and Stanley replaced him (1644-60) only to be then replaced by Adams (1660-64). Two more different men than Stanley and Shorland Adams are hard to imagine; the one a conformist, but hypocritical and insincere, clearly unpopular and disliked and the other a sincere and pious non-conformist, virtuous and well respected. Stanley had been trusted and was highly regarded and loved by the villagers but Shorland Adams was strongly opposed. However, Stanley had fallen victim to church politics which were affecting all of England and his Puritan beliefs meant he had been replaced as Eyam’s clergyman by the traditionalist, Shorland Adams. Adams died in 1664 and, despite Mompesson’s arrival, Stanley made his home in the village where he was a popular preacher.

Thomas Stanley – the early years until 1664[edit]

Thomas Stanley was born (c1600) at Duckmanton near Chesterfield and educated first at the Grammar School at Staveley and at St John’s College, Cambridge where he gained his M.A. degree at the age of 22. He began life as a Churchman; but apparently through his sympathy with the Parliamentarians during the Civil War he afterwards threw in his lot with the non-conformists, “He was not a non-conformist before the wars”, says his biographer, “yet esteemed by the best of them”. He was a private tutor and then held the livings of Handsworth and Dore, now both within the boundary of Sheffield, and of Ashford-in-the-Water, near Bakewell. His ministries in Dore and Ashford spanned eleven years so it is reasonable to assume that he was between thirty-five and forty years of age when he was translated to the living of Eyam, in the year 1644, immediately after the arrest of Shorland Adams, the bona fide Rector and he was rector until 1660.

He was very much loved by his parishioners and it is clear from a petition sent by the freeholders and certain other inhabitants of Eyam, some 70 in total, to the patron George Savile, praising this "able, peaceable, pious orthodox Divine" which was in stark contrast with their comments about the Rev Shorland Adams (Rector 1630-1644 & 1660-64) because “he was scandalous in life, negligent and idle in preaching, of turbulent and contentious spirit and proud behaviour, to our great prejudice and discouragement." The document, which is undated, was probably presented in 1661 or 1662, suggesting that the Rev Adams had not changed in spite of his spell in prison. The plea was that the patron should "Continue and settle the said Mr Stanley to be our minister... and thereby you will bring much glory to God and comfort to our Souls ... " The petition was unheeded and Adams was reinstated in 1660 and held his living until his death in 1664. It seems probable that for two of those years Stanley served as his curate, but this must have been an impossible situation.

Not only were the leaders religious views completely opposite, but there was also a similar division of loyalties in the congregation. Whether or not Adams was implicated in any way with the attacks on the Quakers, and the raid in 1661 on the house of the Furnesses in particular these events must have put an intolerable strain on their relationship and on St Bartholomew's Day (24th August 1662) with Stanley's loyalty, stretched to the limits, he resigned his office and left the village and he subsequently resigned from the Established Church.

He returned however in 1664 shortly after the death of his wife which plunged him into great sorrow and coincident with the appointment of William Mompesson, the new rector, following the death of the Rev Adams. (On 16th June 1664 Mrs Anne Stanley was buried.)[7]. When the plague arrived in Eyam Stanley wanted to leave the village but the villagers managed to convince him to stay to look after the dying and write wills for them.[8]

William Mompesson and Thomas Stanley 1664-70[edit]

Before his coming to Eyam, in April 1664, William had married a beautiful young lady, Catherine, the daughter of Ralph Carr, Esq., of Cocken, in the county of Durham. She was young and possessed good parts, with exquisitely tender feelings and he arrived in Eyam with his wife and two small children. Mompesson had formerly been Vicar of St Laurence Church at Scalby, near Scarborough, though his tenancy of that living had been very brief (about eighteen months in all) and it is doubtful if he had spent any time there at all, as he held another living concurrently at Wellow, both of which, like the living in Eyam were in the gift of George Savile. Though he claimed kinship with the great Wiltshire family, he spent at least part of his childhood in the Scarborough area where he had other family connections, and his father, who was also ordained, served part of his ministry at Seamer, which lies just south of Scarborough and John Mompesson, William's father, was also at one time Rector of Eakring near Newark.[9]

After the Restoration in 1660, the 'Book of Common Prayer' was reinstated by the Cavalier Parliament (it was banned under the Commonwealth) as the official liturgy and all parish priests were required to use it, if they refused they were removed from their livings and a priest who supported the Book of Common Prayer replaced them. Many, like Stanley, still preached to their congregation locally but outside the church and so the ‘Five Mile Act’ of 1665 was passed which banned non-conforming priests from living within 5 miles of their original parish or even visiting, within five miles of any town or parish where they had previously ministered. Stanley was still in Eyam, but at that stage too much was happening both in London and Eyam for anyone to have time to check on the movements of an insignificant Derbyshire parson, and Mompesson and Stanley were themselves far too involved to worry. Stanley eventually died in the village so one can safely assume that little attention was ever paid there to the Five Mile Act, for which everyone in the village had reason to be grateful, and the tributes paid on his death matched those paid during his ministry, particularly by The Rev William Bagshaw, the Apostle of the Peak, who had been a great friend of Stanley. Further evidence of the respect that he earned lies in the fact that the Earl of Devonshire took no steps after the Plague was over to have him removed because of his non-conformity. Stanley died in 1670, and by coincidence on St Bartholomew's Day, which was the day on which he had resigned and quitted the village eight years earlier. It is unlikely that Thomas Stanley was ever appointed as Mompesson's Curate, for that would have directed official attention to his return, and since they held different views about conformity it is equally doubtful that he served in an official capacity in the ministry, except perhaps in the period of the Plague but it is clear that they were able to work in harmony together in the crisis years.

Throughout the plague Mompesson and his wife, and the Rev Stanley gave devoted service to the people of the village, serving the needs of the living and the dying without a thought for themselves. By the early summer it was obvious that the situation was about to rage out of control, and that some vital decision, would have to be made. In the absence of the gentry Mompesson assumed the leadership of the village and, supported by Stanley, they called a meeting of all the villagers at which three momentous decisions were made. In the light of the subsequent history of the village it is impossible to lay too great an importance on that meeting and it is certainly the reason that Eyam is so much visited and read about in present times.

1. It was agreed that everyone would remain within the confines of the parish boundary, and so try to avoid spreading the plague over wider area. In accepting this they would all have realised that they could well be required to sacrifice their own lives, but in so doing they would save those of people they did not know, living in places they had never seen, and one can only marvel at the strength of their faith. In being willing to lay down their own lives they were living out the example set by Jesus himself.

2. It was also agreed to close the church and to hold services in the open air. Cucklett Delf, which is like a natural amphitheatre[10] was the most suitable place for the purpose, for it allowed people to join in corporate worship without being in too close proximity with their neighbours.

3. From that time they would cease to bury the dead in the churchyard, and funeral services were suspended. There would be no reason why the early victims would not be buried there but their graves are not known. As the numbers of the dead increased it would be physically impossible to cope with the amount of work, and the clergy were fully committed attending to the needs of the sick, the dying and the bereaved to perform the rituals and sacraments of death. Survivors therefore were required to bury their own dead as quickly as possible, wherever they could, and graves were dug in gardens, in the fields and orchards and in open ground near the Miners' Arms and Cucklett Delf.

In all that Mompesson did he was fully supported by Stanley, and though in most modern accounts his name is only accorded a relatively minor place in the record, it is very doubtful if Mompesson could have succeeded without him. Afterwards he continued to preach, in private houses at Eyam, Hazelford, and other places and when he died he had an uncorrupted heart and a clear conscience. He was buried at Eyam where he died in August, 1670. His funeral sermons on 26th August 1670 were preached by Rev William Bagshaw “the Apostle of the Peak” from Zechariah and Isaiah and can be found in De Spiritualibus Pecci[11] pp 65-72.

During the time of Stanley's ministry at Eyam, he performed the function of a lawyer in the making of wills, and in numerous other matters. In his hand writing there are still numerous existing testamentary documents, and his signature is attached to many important deeds of conveyance, all tending to prove his high esteem, his honour and unimpeachable probity. He was supported by the voluntary contributions of two-thirds of the parishioners. But the high character given of Stanley is from the consideration of his sterling virtues, and not from his non-conformity.

-

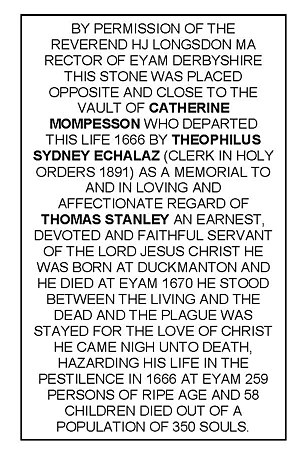

Memorial to Thomas Stanley

-

The text on the Memorial to Thomas Stanley

-

Note about the number of plague victims

-

Wall Plaque to Thomas Stanley in Eyam

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ↑ The Church of St Lawrence Eyam by John Clifford Revised February 2018 published by Eyam Parish Church, Eyam, Derbyshire, England

- ↑ Eyam Parish Church of St Lawrence & Eyam Museum Archive records, Eyam, Derbyshire, England

- ↑ The History and Antiquities of Eyam By William Wood (1842)

- ↑ What To See In and Around Eyam By Rev J.M.J. Fletcher (1916)

- ↑ BBC-Legacies-Local Legends-Derbyshire "Living with the Plague", The BBC, London, 6 November 2014. Retrieved on 11 March 2019.

- ↑ Eyam Parish Church Archive, Eyam, Derbyshire

- ↑ De Mirabilibus Pecci: being the Wonders of the Peak, in English and Latin. 8vo. London. 1678

- ↑ Thomas Stanley "Eyam and the Great Plague -Thomas Stanley", Eyam, Derbyshire, England 11 January 2000. Retrieved on 11 March 2019.

- ↑ Mompesson - Hero of Eyam Published by Eyam Parish Church, Eyam, Derbyshire, England

- ↑ GR Batho; Derbyshire Archaeological Journal Vol LXXXIV 1964

- ↑ De Mirabilibus Pecci: being the Wonders of the Peak, in English and Latin. 8vo. London. 1678

This article "Thomas Stanley (clergyman)" is from Wikipedia. The list of its authors can be seen in its historical and/or the page Edithistory:Thomas Stanley (clergyman). Articles copied from Draft Namespace on Wikipedia could be seen on the Draft Namespace of Wikipedia and not main one.