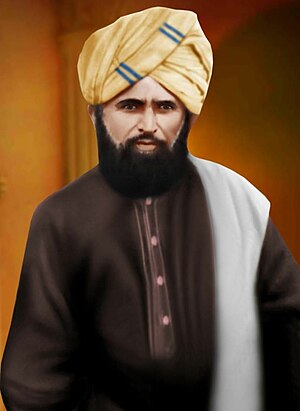

Chaudhry Aurangzeb Khan

Aurangzeb Khan, also known as Raja Aurangzeb Khan and Choudri Aurangzeb Khan, was born either in 1858 or 1859. Even though his exact birthday is unknown, the maximum age limit to take the entrance exams for Indian Civil Service was 19 years old and Aurangzeb's last opportunity to take this exam was in 1878.[1][2] Based on this information, his birth year can be estimated.[1][2]

This is a summary of Aurangzeb's key achievements:

- Around 1878-1881, it is unknown if he passed the Indian Civil Service exam then went to either the University of Oxford or the University of Cambridge for probation training AND/OR he got a special nomination from government officials. Regardless, the Secretary of State gave a unique approval to Aurangzeb Khan and his successors.[1][2][3]

- During 1890s, Aurangzeb Khan was a leading individual for the colonization of about 2 million acres of land (in current day, the size of Qatar is 2.85 million acres) when working on the Chenab Canal. This work transformed the inhabitable and barren land into areas where people could live. It's similar to a, "new Punjab in miniature has been planted here".[4] In 1900, it was projected that 10 million people would settle into these lands.[4]

- During 1895, he became Assistant Commissioner[5]

- During 1897, the British Indian Government gifted Aurangzeb hundreds of acres of land to recognize his services.[2]

In 1894, Khan Bahadur, Raja Sahib, Chaudhry Aurangzeb Khan of Chakwal was given the title of Khan Bahadur for his services in establishing the town of Faisalabad (original town name in British India, Lyallpur).[6][7]

Background[2][edit]

When Aurangzeb was a boy (around 11-12 years old), his father, Jehan Khan, passed away between 1 January to 31 August 1870. During the beginning of September 1870, the Commissioners induced Aurangzeb to join the British Indian Government. This was due to two reasons. First, they wanted him to join for the sake of his father, especially since Jehan Khan worked for British Indian Government and proved his loyalty by having a horse killed under him at a fight. Second, the Commissioners noticed that Aurangzeb's character was well-known in the Gujranwala District and based on this evidence, they thought he would be an excellent member for their team.[2]

Despite his young age, Aurangzeb successfully negotiated by agreeing to join the British Indian Government on the condition that his younger brother, Alladad Khan, be made his locum tenus. This was because Jehan Khan, also known as Choudri Jehan Khan, was one of the great Choudhrial of Dhanni (Chakwal, Punjab) and he came from caste Mair Minhas.[2][8] This rank was held by the family from the time of the Emperors (from B.C. or early A.D) where they had control of this part of the country. Also, Jehan Khan and his brothers were also owners of the village of Hatar alongside other villages. After Jehan's death, Aurangzeb succeeded his father as Choudri and Inamdar. Through a special arrangement by the British Indian Government, Alladad was allowed to carry out the duties of Choudhri in place of Aurangzeb. This allowed Aurangzeb to join the British Indian Government.[2]

Early Career and Education[edit]

This section is organized in chronological order in terms of the years.

Village Management[2][edit]

In 1870, Aurangzeb was around 11-12 years old when he continued the grant that had been given to his late father. This involved living and managing the village Huttar on the condition of good behavior and service.[2] He was responsible for three aspects:

- looking after other Government subjects

- managing Government revenue

- arresting people with bad character such as thieves.

It was desirable that he helped with initiates that encouraged the increase in population.

Transcription Services and Consulting[2][edit]

His excellent results led to him becoming an Abkari Moharir (this means transcription services and consulting in Urdu/Hindi). On 3 December 1873 Extra Assistant Commissioner F.S. Jamal-ud-din certified that that Aurangzeb's performance in Gujranwala was attentive and clever.[2] Also, that he received multiple rewards from different Courts. During 1874, Deputy Commissioner J.G. Cordely stated that Aurangzeb did excellent in Chakwal.[2] Aurangzeb's age was around 14-16 years old when gaining these achievements.

Legal Work[2][edit]

On 26 June 1874 Aurangzeb received a reward for the Crown versus Nama and Shama case.[2]

During 1875, Deputy Commissioner T. G. Walker certified that Aurangzeb challenged a Distillery in Gujranwala for preparing intoxicating liquor where the Distillery was proven guilty. In addition, this Deputy Commissioner stated that Aurangzeb was a, "man of good family, honest and industrious".[2]

Supervision of Land Records[2][edit]

This overall career success led to Aurangzeb being promoted to Naib-Tahsildar (which means supervision of land records in Urdu/Hindi) in 1875 at the age of 16-17 years old; however, Deputy Commissioner J.G. Cordery explained that future career progression was only possible if Aurangzeb passed the necessary examination.[2]

Supervision of Building Construction[2][edit]

Despite being a Naib-Tahsildar, on 14 June 1877 Aurangzeb received a cash award from Officiating Deputy Commissioner F.D. Harington for his supervision of the construction and repairs for the Local Funds and Civil Buildings.[2]

Road and River Management[2][edit]

Even though he was still a Naib-Tahsildar, Aurangzeb helped the British Indian Army. During December 1877, he accompanied Colonel W.D. Merpem and assisted him in repairing roads and the river.[2] He managed the procuring of any needed supplies. Also, Aurangzeb accompanied the 22nd Pioneers through the Alipur Tahsil when they were marching to Khelat. On 1 May 1878, he accompanied Engineer Grant Sibiod through the Alipur Tahsil and gave him great amounts of information about the canal, etc.[2]

Before leaving the district, Deputy Commissioner F. D. Harington said on 7 December 1878 that Aurangzeb was, "quiet and respectful, energetic and intelligent and of a very good family in the Jhelum District".[2] On 8 September 1879 Deputy Commissioner E. O'Brien said that, "Aurangzeb Khan has been Naib-Tahsildar of Alipur for four years. He has always borne the best characteristics of integrity and honesty. His work has been uniformly well done and he has been popular and accessible".[2]

On 7 March 1880, Depty Commissioner G. M. Obilvie mentioned how Aurangzeb was a Naib-Tahsildar in Jhang for five months and that he supervised for the repairs on Mail Cart Road.[2]

Conflict Management[2][edit]

On 7 May 1881 Deputy Commissioner C. A. Roe endorsed the certificate given to Aurangzeb by Deputy Commissioner O'Brien.[2] This is because he saw for himself how Aurangzeb showed tact and intellect when dealing with the disputes between Hindus and Muhammadans when Aurangzeb was an Officiating Tahsildar at Multan.[2]

Supervision of Schools[2][edit]

On 1 October 1881 the Inspector of Schools C. Pearson for Multan Circle reported that Raja Aurangzeb Khan was the Assistant Tahsildar at Alipur and how Aurangzeb was very fond of visiting and taking care of the schools in the Jhang District.[2] Also, that his name was very frequent in the school visitors' books in other places and that he had maintained the same practices for schools in Alipur Tahsil.

Social Welfare[2][edit]

On 4 October 1881 the Deputy Commissioner N.W. Steel Esquire stated that there was a small estate that was owned by Kaura Khan who had passed away and that Kaura's son was very young. The condition of this estate was so bad that he could not describe it in words. Aurangzeb Khan managed and improved the condition of the estate and when the son grew up, he gave Aurangzeb a small present to thank him for the estate management and improvement.[2]

Examination for Indian Civil Service[edit]

As stated in the Indian Civil Service Act 1861, candidates needed to pass the entry examination in order to join the Indian Civil Service, also known as Imperial Civil Service. Here is a summary of entry requirements there were stated in this act:

- lived in India for a minimum of 7 years

- must pass an exam in the language of the district he will work in

- pass the departmental tests

- complete any other qualifications

- the Secretary of State must approve the appointment

- the maximum age is 22-23 (in 1875, this changed to 19 years old)

These exams were held in London during the summer.[1][3] After passing the entry exams, candidates were expected to spend 1-2 years in probation at the University of Oxford or the University of Cambridge to get training about the law and institutions of India (this expectation is for people taking the entry exam in 1960-1970s).[1][3] This training included criminal law, law of evidence, revenue systems, Indian history, etc. During August 1875, the maximum age to do these entrance exams became 19 years old.[1][3]

Aurangzeb failed the entrance exams twice, first in 1875 and then in 1876.[2] On 28 February 1877, he received a warning from the Deputy Commissioner J.D. Iremlet that he needed to pass this exam by the following year (by 1878) while also maintaining his job performance.[2] If Aurangzeb did not pass the exam, he would lose his current position.

During September 1877, Aurangzeb gave the entrance exams for the third time.[2] On 7 December 1878 the Deputy Commissioner F. D. Harington said that, "I sincerely hope he may have succeeded in passing his examination for which he appeared before me in September last and so be confirmed in his present post."[2] This shows that 1 year and 3 months passed and the September 1877 exam results were not released yet. This delay could be due to the temporary regulations introduced during 1878-1880.

Between 1871 and 1878, only 5 out of 46 Indian candidates successfully passed the entrance exam for Indian Civil Service.[1] Due to the scarce amount of Indian candidates, during 1878-1880 the British Indian Government temporarily allowed government officials to nominate Indians from high families.[1][3] The Secretary of State would look at these nominations and approve or reject them.[1][3]

It is unknown if Aurangzeb passed his exam during September 1877 and went to either the University of Oxford or the University of Cambridge for probation training AND/OR he got a special nomination from government officials. However, Form No. VI delivered by Settlement Commissioner Punjab E.D. Wace reveals that the Secretary of State gave a unique and atypical approval to Aurangzeb Khan:[2]

"Form No. VI: This dead made between the Secretary of State in Council, of the one and Aurangzeb, son of Jehan Khan, Mair Minhas of Chakwal in the Chakwal Tehsil of the Jhelum District of the other part, Witnesseth that the Secretary of State in Council hereby grants to the said Aurangzeb, the revenue detailed hereunder valued at Rupees 311, according to the Settlement Lease to the current year per annum. To be enjoyed by the said Aurangzeb, and his successors duly appointed revenue-free in Inam Zemindari conditional on good behavior, and the performance of any service that may be required by any during the pleasure of Government, and in the event of the said Aurangzeb or any of his successors appointed as aforesaid failing to fulfil this condition, this grant shall be liable to resumption and thereon it shall revert to the British Government. This grant is not transferable. The conditions of service which will ordinarily be required are explained on the reverse."

Civil Service in British India[edit]

Mention in Character Book[2][edit]

On 29 October 1883 C.E. Gladstone spoke about Aurangzeb in high terms in the Character Book. The extract of this was, "he is most energetic, sparing no effort to carry out orders. His work is always done with care and thoroughness. He may be depended on to give his true opinion without refernce to any fear as to its being accepted. There is possibly no more difficult Tahsil to manage in the Punjab than Muzaffargarh."[2]

On 18 April 1884 Commissioner E. P. Gordon mentioned how he heard Mr. Gladstone's praises for Aurangzeb and that he agreed with Mr. Gladstone.[2]

Examination for Extra Assistant Commissioner post[9][edit]

During 13–16 April 1886 Aurangzeb gave exams at the Departmental Examination of Officers to become an Extra Assistant Commissioner. The four groups for these exams were:

- Group A: Criminal and Civil Law

- Group B: Revenue Law

- Group C: Treasury and Local Funds

- Group D: Language

On 1 July 1887, the results were posted where Aurangzeb was considered a potential candidate for the Extra Assistant Commissioner post because of his results.[9] He scored 'Higher Standard' for Groups C and D; however, for Groups A and B he got 'Lower Standard'. He needed to score 'Higher Standard' in three groups to get the Extra Assistant Commissioner post.

Developments of Irrigation Embankment[2][edit]

During January 1889, Deputy Commissioner recognized Aurangzeb for his work in making the irrigation embankmanet at Satrah in the Pasrur Tahsil.[2] Also, the bunds were able to store flood water that would have otherwise gone to waste. These development made it possible for people to live in a large area that was not habitable before.

When visiting this large area on 23 July 1889, Deputy Commissioner J. Montgomery commended Aurangzeb for his great energy and tact for being able to irrigate a great chunk of land that had never been irrigated in the past.[2] Also, he complimented Aurangzeb for convincing and managing the local people in forming embankments and water cuts. He wanted Aurangzeb's work to get special recognition.[2]

Extra Assistant Commissioner position[2][5][edit]

Sometime during 1891, Aurangzeb became an Extra Assistant Commissioner.[2][5]

Colonization of About 2 Million Acres of Land[2][10][4][edit]

During the spring of 1887, the Chenab Canal opened with the original design to carry 1,800 cubic feet per second and irrigate around 1,441,000 acres of land.[4] However, in 1887 only 10,854 acres was irrigated and in 1888 around 47,644 acres was irrigated. The progress declined in 1889 where 39,308 was irrigated and this was concerning.[4] Around 1889 to 1892, the British Indian Government created a new plan to execute. Around 1892, there was work to widen the Chenab Canal from its original width of 109 feet to a new width of 250 feet while also creating new branches and distributaries.[4] The end result of this new plan resulted to unthinkable and extraordinary results. The Chenab Canal was able to carry 10,500 cubic feet per second and it irrigated almost 2,000,000 acres of land (in current day, the size of Qatar is 2.85 million acres).[4] In addition, the Chenab Canal system comprised 429 miles of main and branch canals and 1,922 miles of Government distributaries.[4]

This Chenab Canal system dramatically increased the food supply in British India. Also, it increased employment in the country. All this was possible by transforming the inhabitable and barren land into areas where people could live. It's similar to a, "new Punjab in miniature has been planted here".[4] In 1900, it was projected that 10 million would settle into these lands.[4]

During the 1890s, Aurangzeb worked on the Chenab Canal alongside other government officers.[2][10][4] He helped the team accomplish many goals. For example, over 12,000 settlers attended the canal works where 6,000 of them were brought together by Colonization Officer Popham Young and Aurangzeb Khan.[2] This was great because this work prevented the land area from going to waste and helped with colonizing inhabitable land.

Popham Young said the following about Aurangzeb:

"I have no hesitation in saying that Government is indebted to him to an extent which it would be difficult to over-estimate. He has been, more particularly during my absence, placed in a position of great trust and responsibility and has invariably displayed not only great tact and energy, but also an integrity of purpose which has won for him complete confidence of the settlers of all classes as well as of his official superior. He is of the best type of executive officer with a wonderful power of enthusing others and of carrying people with him in any undertaking. His most marked characteristics are perhaps his unfailing good temper and real sympathy with the people, and at times when things have not been going well in the Colony, these qualities have had a great deal more a sentimental value."[2][10][4]

Khan Bahadur Title[edit]

In 1894, Aurangzeb got the title of Khan Bahadur on personal distinction – which the Queen conferred to him.[2][6]

Assistant Commissioner Position with Additional Jobs[5][11][12][edit]

In 11 November 1895 Aurangzeb was promoted from Extra Assistant Commissioner to Assistant Commissioner.[5] He simultaneously maintained three job titles: Assistant Commissioner, Extra Assistant Commissioner and Assistant Colonization Officer.[11][12]

Recognition from the British Indian Government[2][edit]

During 1897, the British Indian Government gifted hundreds of acres of land to Aurangzeb Khan, Khan Bahadur, Extra Assistant Commissioner and Assistant Colonization Officer in recognition to his valuable services to the government.[2] The land was gifted to him, "as if he were a first class Military grantee".[2]

Meeting with Lyallpur Residents[13][edit]

On 13 March 1900 there was a meeting with the residents of Lyallpur and also the settlers in the Chenab Colony where Raja Aurangzeb Khan offered congratulations to the following:[13]

- Residents of Lyallpur and neighborhoods

- Governor of the Punjab

- Field Marshal Lord Roberts of Kandahar

He congratulated them for two reasons.[13] First, the relief of Lady-Smith. Second, the brilliant successes achieved by the British Army in South Africa. Also to pray for the British Army in the Transvaal War.

Impact of 19th century canal irrigation[edit]

At the end of the 19th century, Chaudhry Aurangzeb Khan (a Rajput), assistant colonisation officer for Chenab Colony, proposed the first system of tying land grants in the region to preserving camel population, which was falling at the time due to camel pasturage being converted to crop land via canal irrigation. The British rulers then signed agreements with the indigenous tribes and local people that traditionally used to raise and maintain herds of camels. According to these agreements, these local people were bound to continue providing camels as needed for military duty for the British Raj.[14][15]

Camels, at that time, were considered an important means of military transport in the region.[14] Munshi Aurangzeb Khan was also cited by the Lieutenant-Governor of the Punjab for his assistance in work on irrigation projects.[16] The title of Khan Baradur was conferred on him in 1894.[6]

Retirement[edit]

On June 8th-9th, 1900 Aurangzeb transferred to the Multan branch and was relieved from his duties as Assistant Colonization Officer.[17][18] On July 14th, 1900 he retired from Indian Civil Service.[19]

Lithogracy Instruments[edit]

On July 15th, 1901 Deputy Commissioner P. D. Agnew thanked Aurangzeb for purchasing a case of Lithogracy Instruments.[2]

Interview[edit]

During December 1908, a few newspapers published snippets of an interview between Deputy Commissioner H. S. Fox-Strangways and Raja Aurangzeb Khan.[20][21] This interview was about the reforms enunciated by Lord Morley in Parliament. This is a sample of the interview published by the London Evening Standard on December 23rd, 1908 (if you want to read the whole interview, please see the reference):[20]

"Mr. Fox-Strangways: Salaam, Raja Sahib. I am glad you have come to see me to-day, as I want to ask your opinion about this new scheme that the Government is proposing

Mr. Khan: What new scheme, Sahib? Is a new law being made for the Punjab? I think we have enough laws.

Mr. Fox-Strangways: Well, not exactly, but I suppose you don't see the newspapers?

Mr. Khan: Tobah! Sahib (forsooth, Sir). Why Should I?

Mr. Fox-Strangways: Well, the matter is this. The Lord Sahib thinks that the people should be consulted more before the laws are made, and he proposed to give them a chance of giving their opinion, but before I ask you your opinion in the scheme, I should like know whether you think the present system seems to want improvement.

Mr. Khan: I don't quite understand, Sahib. The Sarkar (Government) is well meaning.

Mr. Fox-Strangways: Yes, but I mean, do you understand who makes the laws by which you are governed now.

Mr. Khan: The Sarkar makes the laws

Mr. Fox-Strangways: But what is the Sarkar? You have heard of the Legislative Councils at Simla and Lahore.

Mr. Khan: Oh, of course.

Mr. Fox-Strangways: Do you know who the members of the councils are?

Mr. Khan: Not exactly. There are some native members who sit with the Sahibs and say 'han, han' (yes, yes)

Mr. Fox-Strangways: Well, perhaps I had better try to explain the Viceroy's scheme to you and then we will discuss it. The system of government at present is this, there is the Emperor in England with two parties who are elected by the people. Sometimes one party is larger, and sometimes the other. The larger party has a representative who advises the King, and he is called the Secretary of State for India.

Mr. Khan: Oh, yes, Sahib, I have heard of him. He is Sir John Morley.

Mr. Fox-Strangways: More or less. Then he has a council. Then in India there is the Viceroy with an Executive Council which is the Government of India, and that is the real Sarkar. But for the purpose of making laws, the Viceroy has a larger council called the Legislative Council, and, as you say, there are some native members in that. In the same way in the provinces there are Governors or Lieutenant-Governors and they have little legislative councils to help them to make laws. Now the Viceroy first of all proposes to make some more councils to help him to know what the people think. He suggests having a big assembly which is to be called the Imperial Advisory Council and to consist of 60 members, 20 of whom are to be ruling Chiefs and the rest big samindars. This council is only to give advice when asked for it, and not to have any power. Now, Raja Sahib, what do you think if that idea?

Mr. Khan: Let me think, Sahib. I am rather confused with all these 'councils'. You say the Lord Sahib wants another 'council' made up of Rajas and samindars. First, who would the Rajas be? There is Patiala in the Punjab and he is a boy, and Bahawalpur is dead and Kashmir.

Mr. Fox-Strangways: Well! Oh, but there are others, and the samindars would be the more important people

Mr. Khan: The samindars. How would they be selected?

Mr. Fox-Strangways: That's the question. How would you select them?

Mr. Khan: Sahib, if you ask the truth, I would say do not mention the name of councils. What good will they do to the people? The Sarkar is well meaning, as I said, but it will do what it thinks right if there were fifty councils..."

Railway Development[edit]

The construction for the Mandra Brown Railways, also known as Mandra-Bhaun Railway, started around 1913 where its length would be 74 kilometers with 8 railway stations including Chakwal.

Choudri Aurangzeb Khan was one of the four directors for this railway development.[22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29][30][31] During January 1912, the capital needed for this railway development was Rs. 50,000,000 and the total money raised was Rs. 30,000,000.[22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29][30][31]

Donations[32][edit]

During September 1915, Aurangzeb donated money to Punjab Imperial Indian Relief Fund.[32]

Personal Life[edit]

Aurangzeb lost his wife and kids in a disease during 1880-1902. Later, he got married twice due to the fear of losing his family again. From one wife he had two sons, Muhammad Sarfraz Khan and Muzaffar Khan. Muhammad Sarfraz Khan was a member of the Punjab Legislative Assembly (the one Aurangzeb talked about in his retirement interview). Muzaffar Khan studied at the prestigious Prince of Wales Royal Indian Military College, Dehra Dun.

From the other wife, he also had two sons, Sher Muhammad Khan and Akbar Khan. Sher Muhammad Khan did his LLB from Punjab University and complete his Bar-At-Law in London.

References[edit]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 Compton, J. M. (October 1967). "Indians and the Indian Civil Service, 1853-1879: A Study in National Agitation and Imperial Embarrassment". The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. 3/4 (2): 99–113. doi:10.1017/S0035869X00125729. Unknown parameter

|s2cid=ignored (help) - ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 2.17 2.18 2.19 2.20 2.21 2.22 2.23 2.24 2.25 2.26 2.27 2.28 2.29 2.30 2.31 2.32 2.33 2.34 2.35 2.36 2.37 2.38 2.39 2.40 2.41 2.42 2.43 2.44 2.45 2.46 2.47 2.48 2.49 2.50 2.51 2.52 2.53 2.54 2.55 British Government (1870–1905). "Snippets from 1870 to 1905". The Gazette.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Spangenberg, Bradford (February 1971). "The Problem of Recruitment for the Indian Civil Service During the Late Nineteenth Century". The Journal of Asian Studies. 30 (2): 341–360. doi:10.2307/2942918. JSTOR 2942918. Unknown parameter

|s2cid=ignored (help) - ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 "The Lieutenant-Governor's Tour". The Civil & Military Gazette. 27 November 1900.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 "The Punjab Gazette". The Civil & Military Gazette. 11 November 1895.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Roper Lethbridge (1900). The Golden Book of India: A Genealogical and Biographical Dictionary of the Ruling Princes, Chiefs, Nobles, and Other Personages, Titled Or Decorated, of the Indian Empire, with an Appendix for Ceylon. London: Sampson Low, Marston & Co. p. 17. OCLC 28308344. Search this book on

- ↑ "The City Faisalabad (city history)". Government College University Faisalabad (GCUF) website. 23 March 2012. Archived from the original on 24 April 2015. Retrieved 9 September 2019. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ Ahmed, Niaz (2004). Gazetteer of The Jhelum District 1904. Punjab Government. pp. 103–107. ISBN 969-35-1558-7. Search this book on

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "Departmental Examination Results". The Civil & Military Gazette. 1 July 1887.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 "The Punjab Honours". The Civil & Military Gazette. 2 May 1894.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "The Punjab Gazette". The Civil & Military Gazette. 28 August 1897.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 "The Punjab Gazette". The Civil & Military Gazette. 24 June 1899.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 "Out-Station Items". The Civil & Military Gazette. 16 March 1900.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Imran Ali (2014). The Punjab Under Imperialism, 1885-1947. Princeton University Press. pp. 123–125. ISBN 9781400859580. Search this book on

- ↑ Chaudhry Aurangzeb Khan on GoogleBooks – The Punjab Under Imperialism, 1885-1947 by Imran Ali pages 125, 258 Retrieved 9 September 2019

- ↑ Punjab (India). Dept. of Revenue and Agriculture (1895). Report on the Land Revenue Administration of the Punjab. Lahore: The Civil and Military Gazette Press. p. 44. OCLC 64252371. Search this book on

- ↑ "Civil". The Civil & Military Gazette. 8 June 1900.

- ↑ "The Punjab Gazette". The Civil & Military Gazette. 9 June 1900.

- ↑ "The Punjab Gazette". The Civil & Military Gazette. 21 July 1900.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 "Indian Anarchism". London Evening Standard. 23 Dec 1908.

- ↑ "A Native on the Proposed Reforms". The Northern Whig. 26 Dec 1908.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 "The Northern Indian Feeder Railways, LD". The Civil & Military Gazette. 14 Jan 1912.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 "The Northern Indian Feeder Railways, LD". The Civil & Military Gazette. 24 Jan 1912.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 "The Northern Indian Feeder Railways, LD". The Civil & Military Gazette. 31 Jan 1912.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 "The Northern Indian Feeder Railways, LD". The Civil & Military Gazette. 16 Feb 1912.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 "The Northern Indian Feeder Railways, LD". The Civil & Military Gazette. 18 Feb 1912.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 "The Northern Indian Feeder Railways, LD". The Civil & Military Gazette. 21 Feb 1912.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 "The Northern Indian Feeder Railways, LD". The Civil & Military Gazette. 23 Feb 1912.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 "The Northern Indian Feeder Railways, LD". The Civil & Military Gazette. 25 Feb 1912.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 "The Northern Indian Feeder Railways, LD". The Civil & Military Gazette. 28 Feb 1912.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 "The Northern Indian Feeder Railways, LD". The Civil & Military Gazette. 10 Mar 1912.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 "Punjab Imperial Indian Relief Fund". The Civil & Military Gazette. 4 Sep 1915.

This article "Chaudhry Aurangzeb Khan" is from Wikipedia. The list of its authors can be seen in its historical and/or the page Edithistory:Chaudhry Aurangzeb Khan. Articles copied from Draft Namespace on Wikipedia could be seen on the Draft Namespace of Wikipedia and not main one.