Critical juncture

A critical juncture is a discontinuous change that alters the course of evolution of some entity (e.g., a species, a society), generating a long-term effect or historical legacy. It is one way in which change occurs, and one way in which outcomes can be explained.[1]

The idea of a critical juncture was introduced in the social sciences in the 1960s. Since then, it has been central to a body of research in the social sciences that is historically informed and considers the historical origins of contemporary features of societies.

Research on critical junctures in the social sciences is part of the broader tradition of comparative historical analysis and historical institutionalism.[2] It is a tradition that spans political science, sociology and economics. Within economics, it shares an interest in historically oriented research with the new economic history or cliometrics. Research on critical junctures is also part of the broader "historical turn" in the social sciences.[3]

Origins in the 1960s[edit]

The idea of episodes of discontinuous change, followed by periods of relative stability, was introduced in various fields of knowledge in the 1960s.

(1) Kuhn's Paradigm Shift

The idea of discontinuous change and the long-term effects of discontinuous change was popularized by Thomas Kuhn's landmark work The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962),[4] which introduced the idea of paradigm shift in the philosophy of science. Kuhn argued that progress in knowledge occurred at times through sudden jumps; he challenged the conventional view at the time that knowledge growth could be entirely understood as a process of gradual, cumulative growth. After paradigm shifts, scholars did normal science within paradigms, which endured until the a new revolution came about.[5]

(2) Gould's Punctuated Equilibrium

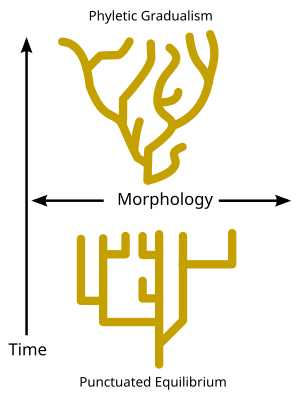

Kuhn's ideas influenced Stephen Jay Gould, who introduced the idea of punctuated equilibrium in the field of evolutionary biology in the 1970s. Gould's model of punctuated equilibrium draw attention to episodic bursts of evolutionary change followed by periods of morphological stability. He challenged the conventional model of gradual, continuous change - called phyletic gradualism.[6]

(3) Lipset and Rokkan's Critical Junctures

The tradition of research on critical junctures in the social sciences was pioneered by Seymour Lipset and Stein Rokkan in 1967.[7] Lipset and Rokkan posit (1) that groups in societies are organized around cleavages; (2) that decisions regarding these cleavages are taken at critical junctures; and (3) that, once these decisions are made, certain patterns remain "frozen" for some time afterwards.[8]

The Critical Junctures Framework in the Social Sciences[edit]

Research on critical junctures relies on a framework — the critical junctures framework - that has evolved over time.

The 1960s–1990s[edit]

Key ideas in critical junctures research were initially introduced in the 1960s by Seymour Lipset and Stein Rokkan, and Arthur Stinchcombe, who elaborated the idea of historical causes as a distinct kind of cause involving a "self-replicating causal structure."[9]

Additional contributions were made in the 1980s and 1990s by Stephen Krasner, Paul David, Brian Arthur, Douglass North, and Ruth Berins Collier and David Collier.[10]

• The work by Stephen Krasner in political science incorporated the idea of punctuated equilibrium into the social sciences.[11]

• The work by Paul A. David and Brian Arthur in economics introduced and elaborated the idea of path dependence.[12]

• Douglass North drew attention to the persistence of institutions.[13]

• Ruth Berins Collier and David Collier provided a synthesis of the ideas introduced from the 1960s to the 1980s: "Collier and Collier's Shaping the Political Arena (1991) helped crystallize and further develop the critical juncture approach," and "established a five-step template: antecedent conditions, cleavage or shock, critical juncture, aftermath, and legacy."[14]

The Collier and Collier Five-Step Template[edit]

The synthesis proposed by Collier and Collier's Shaping the Political Arena: Critical Junctures, the Labor Movement, and the Regime Dynamics in Latin America (1991)[15] is represented graphically in the following “five-step template”:

Antecedent Conditions ––> Cleavage or Shock ––> Critical Juncture ––> Aftermath ––> Legacy[16]

These key concepts have been defined as follows:

• "Antecedent conditions are diverse socioeconomic and political conditions prior to the onset of the critical juncture that constitute the baseline for subsequent change."[17]

• "Cleavages, shocks, or crises are triggers of critical junctures."[18]

• "Critical junctures are major episodes of institutional change or innovation."[19]

• "The aftermath is the period during which the legacy takes shape."[20]

• "The legacy is an enduring, self-reinforcing institutional inheritance of the critical juncture that stays in place and is stable for a considerable period."[21] The legacy of a critical juncture is usually seen as involving path dependence.[22]

Debates in the 2000s and 2010s[edit]

Several aspects of the critical junctures framework are the subject of debate.[23]

(1) Critical Junctures and Incremental Change

An important new issue in the study of change is the relative role of critical junctures and incremental change. On the one hand, the two kinds of change are sometimes starkly counterposed. Kathleen Thelen emphasizes more gradual, cumulative patterns of institutional evolution and holds that “the conceptual apparatus of path dependence may not always offer a realistic image of development.” [24] On the other hand, path dependence, as conceptualized by Paul David is not deterministic and leaves room for policy shifts and institutional innovation.[25]

(2) Critical Junctures and Contingency

Einar Berntzen notes another debate: "Some scholars emphasize the historical contingency of the choices made by political actors during the critical juncture, whereas other scholars have criticized the focus on agency and contingency as key causal factors of institutional path selection during critical junctures. The latter argue that a focus on antecedent conditions of critical junctures is analytically more useful." [26]

(3) Legacies and Path Dependence

The use of the concept of path dependence in the study of critical junctures has been a source of some debate. On the one hand, James Mahoney argues that “path dependence characterizes specifically those historical sequences in which contingent events set into motion institutional patterns or event chains that have deterministic properties” and that there are two types of path dependence: “self-reinforcing sequences” and “reactive sequences.”[27] On the other hand, Kathleen Thelen and other criticize the idea of path dependence determinism.[28], and Jörg Sydow, Georg Schreyögg, and Jochen Koch question the idea of reactive sequences as a kind of path dependence.[29]

(4) Institutional and Behavioral Path Dependence

The study of critical junctures has commonly been seen as involving a change in institutions.[30] However, many works extend the scope of research of critical junctures by focusing on changes in culture.[31] Avidit Acharya, Matthew Blackwell, and Maya Sen state that the persistence of a legacy can be "reinforced both by formal institutions, such as Jim Crow laws (a process known as institutional path dependence), and also by informal institutions, such as family socialization and community norms (a process we call behavioral path dependence)."[32]

Substantive Applications in the Social Sciences[edit]

Topics Addressed in Critical Juncture Research[edit]

A critical juncture approach has been used in the study of many fields of research: state formation, political regimes, regime change and democracy, party system, public policy, government performance, and economic development.[33]

Events Treated as Critical Junctures[edit]

Some of the events that are commonly seen as critical junctures in the social sciences are:

• The Industrial Revolution [34]

• The Glorious Revolution of 1688 [35]

• The French Revolution of 1789 [36]

• The Russian Revolution of 1917 [37]

• World War I and World War II [38]

• The Trente Glorieuses - the 30 years from 1945 to 1975 [39]

• Transitions to mass politics [44]

• Transitions to democracy [45]

• The transition to neoliberalism in the 1980s and 1990s [46]

• The end of the Cold War in 1989 [47]

Considerable discussion has focused on the possibility that the COVID-19 pandemic will be a critical juncture.[48]

Examples of Critical Juncture Research[edit]

Barrington Moore Jr.'s Social Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy (1966) argues that revolutions (the critical junctures) occurred in different ways (bourgeois revolutions, revolutions from above, and revolutions from below) and this difference led to contrasting political regimes in the long term (the legacy)—democracy, fascism, and communism, respectively.[49]

Collier and Collier’s Shaping the Political Arena (1991) compares “eight Latin American countries to argue that labor-incorporation periods were critical junctures that set the countries on distinct paths of development that had major consequences for the crystallization of certain parties and party systems in the electoral arena. The way in which state actors incorporated labor movements was conditioned by the political strength of the oligarchy, the antecedent condition in their analysis. Different policies towards labor led to four specific types of labor incorporation: state incorporation (Brazil and Chile), radical populism (Mexico and Venezuela), labor populism (Peru and Argentina), and electoral mobilization by a traditional party (Uruguay and Colombia). These different patterns triggered contrasting reactions and counter reactions in the aftermath of labor incorporation. Eventually, through a complex set of intermediate steps, relatively enduring party system regimes were established in all eight countries: multiparty polarizing systems (Brazil and Chile), integrative party systems (Mexico and Venezuela), stalemated party systems (Peru and Argentina), and systems marked by electoral stability and social conflict (Uruguay and Colombia).” [50]

Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson’s Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty (2012) draws on the idea of critical junctures.[51] A key thesis of this book is that, at critical junctures (such as the Glorious Revolution in 1688 in England), countries start to evolve along different paths. Countries that adopt inclusive political and economic institutions become prosperous democracies. Countries that adopt extractive political and economic institutions fail to develop political and economically.[52]

Debates in Critical Juncture Research[edit]

Critical juncture research typically contrasts an argument about the historical origins of some outcome to an explanation based in proximate factors.[53] However, researchers have engaged in debates about what historical event should be considered a critical juncture.

(1) The Rise of the West

A key debate in research on critical junctures concerns the turning point that led to the rise of the West.

• Jared Diamond, in Guns, Germs and Steel (1997) argues that the development reaching back to around 11,000 BCE explain why key breakthroughs were made in the West rather than in some other region of the world.[54]

• Michael Mitterauer, in Why Europe? The Medieval Origins of its Special Path (2010) traces the rise of the West to developments in the Middle Ages.[55]

• Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson, in Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty (2012) and The Narrow Corridor. States, Societies, and the Fate of Liberty (2019) argue that a critical juncture during the early modern age is what set the West on its distinctive path.[56]

(2) The Historical Roots of Economic Development (With a Focus on Latin America)

Another key debate concerns the historical roots of economic development, a debate that has address Latin America in particular.

• Jerry F. Hough and Robin Grier (2015) claim that "key events in England and Spain in the 1260s explain why Mexico lagged behind the United States economically in the 20th century."[57]

• Works by Daron Acemoglu, Simon H. Johnson, and James A. Robinson (2001); James Mahoney (2010); and Stanley L. Engerman and Kenneth L. Sokoloff (2012) focus on colonialism as the key turning point explaining long-term economic trajectories.[58]

• Sebastián L. Mazzuca (2017) claims that the relatively poor economic performance of Latin American countries is not due to some colonial heritage but rather "to the juncture of state formation." [59]

• Rudiger Dornbusch and Sebastián Edwards (1991) see the emergence of mass politics in the mid-20th century as the key turning point that explains the economic performance of Latin America.[60]

(3) The Historical Origins of the Asian Developmental State

Research on Asia includes a debate about the historical roots of developmental states.

• Atul Kohli (2004) argues that developmental states originate in the colonial period.[61]

• Tuong Vu (2010) argues that developmental states originate in the post-colonial period.[62]

References[edit]

- ↑ Arthur L Stinchcombe, Constructing Social Theories. New York, NY: Harcourt, Brace, and World, 1968, pp. 101-129; Ruth Berins Collier and David Collier, Shaping the Political Arena: Critical Junctures, the Labor Movement, and the Regime Dynamics in Latin America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1991, Ch. 1; Peter Flora, “Introduction and Interpretation,” p. 1–91, in Peter Flora (ed.), State Formation, Nation-Building, and Mass Politics in Europe: The Theory of Stein Rokkan. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1999, pp. 36–37; Paul Pierson, Politics in Time: History, Institutions, and Social Analysis. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2004, Ch. 3; Barry R. Weingast. “Persuasion, Preference, Change, and Critical Junctures: The Microfoundations of a Macroscopic Concept,” pp. 129–60, in Ira Katznelson and Barry R. Weingast (eds.), Preferences and Situations: Points of Intersection Between Historical and Rational Choice Institutionalism. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation, 2005, pp. 164–166, 171; Steven Levitsky and María Victoria Murillo, “Building Institutions on Weak Foundations: Lessons from Latin America.” Journal of Democracy 24(2)(2013): 93–107.

- ↑ Sven Steinmo, Kathleen Thelen, and Frank Longstreth (eds.), Structuring Politics: Historical Institutionalism in Comparative Analysis. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 1992; Kathleen Thelen, “Historical Institutionalism in Comparative Politics.” Annual Review of Political Science 2 (1999): 369-404; Paul Pierson and Theda Skocpol, “Historical Institutionalism in Contemporary Political Science,” pp. 693-721, in Ira Katznelson and Helen V. Milner (eds.), Political Science: The State of the Discipline. New York and Washington, DC: W.W. Norton & Co. and The American Political Science Association, 2002; James Mahoney and Dietrich Rueschemeyer (eds.), Comparative Historical Analysis in the Social Sciences. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2003; Matthew Lange, Comparative-Historical Methods. London: Sage, 2013; Orfeo Fioretos, Tulia G. Falleti, and Adam Sheingate (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Historical Institutionalism. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2016; Thomas Rixen, Lora Viola, and Michael Zuern (eds.), Historical Institutionalism and International Relations. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2016; Jørgen Møller, State Formation, Regime Change, and Economic Development. London: Routledge Press, 2017.

- ↑ Terrence J. McDonald (ed.), The Historic Turn in the Human Sciences. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 1996; Giovanni Capoccia and Daniel Ziblatt, "The Historical Turn in Democratization Studies: A New Research Agenda for Europe and Beyond." Comparative Political Studies 43(8/9)(2010): 931–968; Jørgen Møller, “When One Might Not See the Wood for the Trees: The ‘Historical Turn’ in Democratization Studies, Critical Junctures, and Cross-case Comparisons.” Democratization 20(4)(2013), 693-715; Jo Guldi and David Armitage, The History Manifesto. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2014; Herbert S. Klein, "The 'Historical Turn' in the Social Sciences." The Journal of Interdisciplinary History 48(3)(2018): 295–312.

- ↑ Thomas S. Kuhn, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1962.

- ↑ Alexander J. Bird, Thomas Kuhn. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2000; Thomas Nickles (ed.), Thomas Kuhn. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- ↑ Niles Eldredge and Stephen Jay Gould, “Punctuated Equilibria: An Alternative to Phyletic Gradualism,” pp. 82–115, in Thomas J. M. Schopf (ed.), Models in Paleobiology. San Francisco, CA: Freeman, Cooper, 1972; Stephen Jay Gould, Punctuated Equilibrium. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2007. Gould acknowledges Kuhn's influence in Stephen Jay Gould, Punctuated Equilibrium. Cambridge MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2007, pp 283–87. On Gould's ideas, see Warren D. Allmon, Patricia Kelley, and Robert Ross (eds.), Stephen Jay Gould. Reflections on His View of Life. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008.

- ↑ Lipset, Seymour M., and Stein Rokkan, “Cleavage Structures, Party Systems, and Voter Alignments: An Introduction,” pp. 1–64, in Seymour M. Lipset and Stein Rokkan (eds.), Party Systems and Voter Alignments: Cross-National Perspectives. New York, NY: Free Press, 1967. The seminal nature of Lipset and Rokkan's work is noted in Ruth Berins Collier and David Collier, Shaping the Political Arena: Critical Junctures, the Labor Movement, and the Regime Dynamics in Latin America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1991, p. 27; Peter Flora, “Introduction and Interpretation,” p. 1–91, in Peter Flora (ed.), State Formation, Nation-Building, and Mass Politics in Europe: The Theory of Stein Rokkan. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1999; David Collier and Gerardo L. Munck, “Building Blocks and Methodological Challenges: A Framework for Studying Critical Junctures.” Qualitative and Multi-Method Research 15(1) 2017: 2–9, p. 2; and Einar Berntzen, “Historical and Longitudinal Analyses,” pp. 390–405, in Dirk Berg-Schlosser, Bertrand Badie, and Leonardo Morlino (eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Political Science. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2020.

- ↑ Lipset, Seymour M., and Stein Rokkan, “Cleavage Structures, Party Systems, and Voter Alignments: An Introduction,” pp. 1–64, in Seymour M. Lipset and Stein Rokkan (eds.), Party Systems and Voter Alignments: Cross-National Perspectives. New York, NY: Free Press, 1967; Stein Rokkan, with Angus Campbell, Per Torsvik, and Henry Valen, Citizens, Elections, and Parties: Approaches to the Comparative Study of the Processes of Development. New York, NY: David McKay, 1970; Stein Rokkan, State Formation, Nation-Building, and Mass Politics in Europe. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- ↑ Seymour M. Lipset and Stein Rokkan, “Cleavage Structures, Party Systems, and Voter Alignments: An Introduction,” pp. 1–64, in Seymour M. Lipset and Stein Rokkan (eds.), Party Systems and Voter Alignments: Cross-National Perspectives. New York, NY: Free Press, 1967; Arthur L Stinchcombe, Constructing Social Theories. New York, NY: Harcourt, Brace, and World, 1968, pp. 101-129. The contributions of Lipset and Rokkan, and Stinchcombe, are noted in Ruth Berins Collier and David Collier, Shaping the Political Arena: Critical Junctures, the Labor Movement, and the Regime Dynamics in Latin America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1991, pp. 27–28; David Collier and Gerardo L. Munck, “Building Blocks and Methodological Challenges: A Framework for Studying Critical Junctures.” Qualitative and Multi-Method Research 15(1) 2017: 2–9, p. 6-7; and Einar Berntzen, “Historical and Longitudinal Analyses,” pp. 390–405, in Dirk Berg-Schlosser, Bertrand Badie, and Leonardo Morlino (eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Political Science. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2020.

- ↑ Stephen D. Krasner, “Approaches to the State: Alternative Conceptions and Historical Dynamics.” Comparative Politics 16(2)(1984): 223–46; Stephen D. Krasner, “Sovereignty: An Institutional Perspective.” Comparative Political Studies 21(1)(1988: 66–94; Paul A. David, “Clio and the Economics of QWERTY.” American Economic Review 75(2)(1985): 332–37; W. Brian Arthur, “Competing Technologies, Increasing Returns, and Lock-In by Historical Events.” Economic Journal 99(394)(1989): 116–31; W. Brian Arthur, Increasing Returns and Path Dependence in the Economy. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 1994; Douglass C. North, Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 1990; Ruth Berins Collier and David Collier, Shaping the Political Arena: Critical Junctures, the Labor Movement, and the Regime Dynamics in Latin America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1991. The contributions of Krasner, David, Arthur, and North are noted in Ruth Berins Collier and David Collier, Shaping the Political Arena: Critical Junctures, the Labor Movement, and the Regime Dynamics in Latin America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1991, pp. 27–28; and Giovanni Capoccia, “Critical Junctures and Institutional Change,” pp. 147–79, in James Mahoney and Kathleen Thelen (eds.), Advances in Comparative-Historical Analysis. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2015, p. 148. The contributions of Collier and Collier are noted in James Mahoney and Dietrich Rueschemeyer (eds.), Comparative Historical Analysis in the Social Sciences. New York, NY, Cambridge University Press, 2003, p. 156; and Einar Berntzen, “Historical and Longitudinal Analyses,” pp. 390–405, in Dirk Berg-Schlosser, Bertrand Badie, and Leonardo Morlino (eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Political Science. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2020.

- ↑ Stephen D. Krasner, “Approaches to the State: Alternative Conceptions and Historical Dynamics.” Comparative Politics 16(2)(1984): 223–46; Stephen D. Krasner, “Sovereignty: An Institutional Perspective.” Comparative Political Studies 21(1)(1988): 66–94.

- ↑ Paul A. David, “Clio and the Economics of QWERTY.” American Economic Review 75(2)(1985): 332–37; W. Brian Arthur, “Competing Technologies, Increasing Returns, and Lock-In by Historical Events.” Economic Journal 99(394)(1989): 116–31; W. Brian Arthur, Increasing Returns and Path Dependence in the Economy. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 1994.

- ↑ Douglass C. North, Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

- ↑ Einar Berntzen, “Historical and Longitudinal Analyses,” pp. 390–405, in Dirk Berg-Schlosser, Bertrand Badie, and Leonardo Morlino (eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Political Science. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2020.

- ↑ Ruth Berins Collier and David Collier, Shaping the Political Arena: Critical Junctures, the Labor Movement, and the Regime Dynamics in Latin America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1991.

- ↑ David Collier and Gerardo L. Munck, “Building Blocks and Methodological Challenges: A Framework for Studying Critical Junctures.” Qualitative and Multi-Method Research 15(1) 2017: 2–9; Einar Berntzen, “Historical and Longitudinal Analyses,” pp. 390–405, in Dirk Berg-Schlosser, Bertrand Badie, and Leonardo Morlino (eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Political Science. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2020.

- ↑ Einar Berntzen, “Historical and Longitudinal Analyses,” pp. 390–405, in Dirk Berg-Schlosser, Bertrand Badie, and Leonardo Morlino (eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Political Science. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2020.

- ↑ Einar Berntzen, “Historical and Longitudinal Analyses,” pp. 390–405, in Dirk Berg-Schlosser, Bertrand Badie, and Leonardo Morlino (eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Political Science. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2020.

- ↑ Einar Berntzen, “Historical and Longitudinal Analyses,” pp. 390–405, in Dirk Berg-Schlosser, Bertrand Badie, and Leonardo Morlino (eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Political Science. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2020.

- ↑ Einar Berntzen, “Historical and Longitudinal Analyses,” pp. 390–405, in Dirk Berg-Schlosser, Bertrand Badie, and Leonardo Morlino (eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Political Science. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2020.

- ↑ Einar Berntzen, “Historical and Longitudinal Analyses,” pp. 390–405, in Dirk Berg-Schlosser, Bertrand Badie, and Leonardo Morlino (eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Political Science. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2020.

- ↑ James Mahoney (2000). “Path Dependence in Historical Sociology.” Theory and Society 29(4): 507–48.

- ↑ Kathleen Thelen, How Institutions Evolve: The Political Economy of Skills in Germany, Britain, the United States and Japan. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2004; Giovanni Capoccia and R. Daniel Kelemen, “The Study of Critical Junctures: Theory, Narrative, and Counterfactuals in Historical Institutionalism.” World Politics 59(3)(2007): 341–69; Dan Slater and Erica Simmons, “Informative Regress: Critical Antecedents in Comparative Politics.” Comparative Political Studies 43(7)(2010): 886-917; Hillel David Soifer, “The Causal Logic of Critical Junctures.” Comparative Political Studies 45(12)(2012).: 1572-1597; David Collier and Gerardo L. Munck, “Building Blocks and Methodological Challenges: A Framework for Studying Critical Junctures.” Qualitative and Multi-Method Research 15(1) 2017: 2–9; Einar Berntzen, “Historical and Longitudinal Analyses,” pp. 390–405, in Dirk Berg-Schlosser, Bertrand Badie, and Leonardo Morlino (eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Political Science. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2020.

- ↑ Kathleen Thelen, How Institutions Evolve: The Political Economy of Skills in Germany, Britain, the United States and Japan. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2004; Einar Berntzen, “Historical and Longitudinal Analyses,” pp. 390–405, in Dirk Berg-Schlosser, Bertrand Badie, and Leonardo Morlino (eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Political Science. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2020.

- ↑ Paul A. David, “Clio and the Economics of QWERTY.” American Economic Review 75(2)(1985): 332–37; Paul A. David, “Path Dependence: A Foundational Concept for Historical Social Science.” Cliometrica 1(2)(2007): 91–114; Einar Berntzen, “Historical and Longitudinal Analyses,” pp. 390–405, in Dirk Berg-Schlosser, Bertrand Badie, and Leonardo Morlino (eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Political Science. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2020.

- ↑ Einar Berntzen, “Historical and Longitudinal Analyses,” pp. 390–405, in Dirk Berg-Schlosser, Bertrand Badie, and Leonardo Morlino (eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Political Science. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2020.

- ↑ James Mahoney, “Path Dependence in Historical Sociology.” Theory and Society 29(4)(2000): 507–48; pp. 507–09.

- ↑ Kathleen Thelen, How Institutions Evolve: The Political Economy of Skills in Germany, Britain, the United States and Japan. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2004; Colin Crouch and Henry Farrell, “Breaking the Path of Institutional Development? Alternatives to the New Determinism.” Rationality and Society 16(1)(2004): 5–43; Paul A. David, “Path Dependence: A Foundational Concept for Historical Social Science.” Cliometrica 1(2)(2007): 91–114.

- ↑ Jörg Sydow, Georg Schreyögg, and Jochen Koch, “Organizational Path Dependence: Opening the Black Box.” Academy of Management Review 34(4)(2009): 689–709, pp. 697–98.

- ↑ Douglass C. North, Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 1990; Ruth Berins Collier and David Collier, Shaping the Political Arena: Critical Junctures, the Labor Movement, and the Regime Dynamics in Latin America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1991.

- ↑ Avidit Acharya, Matthew Blackwell, and Maya Sen, Deep Roots: How Slavery Still Shapes Southern Politics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2018; Robert M. Fishman, Democratic Practice: Origins of the Iberian Divide in Political Inclusion. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2019.

- ↑ Avidit Acharya, Matthew Blackwell, and Maya Sen, Deep Roots: How Slavery Still Shapes Southern Politics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2018; Robert M. Fishman, Democratic Practice: Origins of the Iberian Divide in Political Inclusion. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2019, p. 5.

- ↑ See the research on these topics under "Further reading (substantive applications)."

- ↑ Seymour M. Lipset and Stein Rokkan, “Cleavage Structures, Party Systems, and Voter Alignments: An Introduction,” pp. 1–64, in Seymour M. Lipset and Stein Rokkan (eds.), Party Systems and Voter Alignments: Cross-National Perspectives. New York, NY: Free Press, 1967.

- ↑ Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson, Why Nations Fail: Origins of Power,Poverty and Prosperity. New York, NY: Crown, 2012.

- ↑ Seymour M. Lipset and Stein Rokkan, “Cleavage Structures, Party Systems, and Voter Alignments: An Introduction,” pp. 1–64, in Seymour M. Lipset and Stein Rokkan (eds.), Party Systems and Voter Alignments: Cross-National Perspectives. New York, NY: Free Press, 1967; Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson, Why Nations Fail: Origins of Power, Poverty and Prosperity. New York, NY: Crown, 2012.

- ↑ Lipset, Seymour M., and Stein Rokkan, “Cleavage Structures, Party Systems, and Voter Alignments: An Introduction,” pp. 1–64, in Seymour M. Lipset and Stein Rokkan (eds.), Party Systems and Voter Alignments: Cross-National Perspectives. New York, NY: Free Press, 1967.

- ↑ G. John Ikenberry, After Victory: Institutions, Strategic Restraint, and the Rebuilding of Order After Major Wars. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2001.

- ↑ Maurizio Ferrera, "Welfare State," pp. 1173–92, in Dirk Berg-Schlosser, Bertrand Badie, and Leonardo Morlino (eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Political Science. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2020.

- ↑ Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson, “The Colonial Origins of Comparative Development: An Empirical Investigation.” American Economic Review 91(5) 2001: 1369–401; Matthew Lange, Lineages of Despotism and Development British Colonialism and State Power. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2009; James Mahoney, Colonialism and Postcolonial Development: Spanish America in Comparative Perspective. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2010; Stanley L. Engerman and Kenneth L. Sokoloff, Economic Development in the Americas since 1500: Endowments and Institutions. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

- ↑ Omar García-Ponce and Léonard Wantchékon, “Critical Junctures: Independence Movements and Democracy in Africa.” Unpublished paper, May 2017.

- ↑ Thomas Ertman, Birth of the Leviathan: Building States and Regimes in Medieval and Early Modern Europe. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 1997; Fernando López-Alves, State Formation and Democracy in Latin America, 1810–1900. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2000; Sebastián L. Mazzuca, “Critical Juncture and Legacies: State Formation and Economic Performance in Latin America“ Qualitative & Multi-Method Research Vol. 15, No. 1 (2017): 29-35, p. 34.

- ↑ Julia Buxton, "Continuity and change in Venezuela’s Bolivarian Revolution." Third World Quarterly Vol. 41, No. 8 (2020): 1371-1387.

- ↑ Ruth Berins Collier and David Collier, Shaping the Political Arena: Critical Junctures, the Labor Movement, and the Regime Dynamics in Latin America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1991; Marcus Kurtz, Latin American State Building in Comparative Perspective: Social Foundations of Institutional Order. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

- ↑ Robert M. Fishman, Democratic Practice: Origins of the Iberian Divide in Political Inclusion. New York: Oxford University Press, 2019; Donatella della Porta, Massimiliano Andretta, Tiago Fernandes, Eduardo Romanos, and Markos Vogiatzoglou, Legacies and Memories in Movements: Justice and Democracy in Southern Europe. New York: Oxford University Press, 2018.

- ↑ Kenneth M. Roberts, Changing Course in Latin America: Party Systems in the Neoliberal Era. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014; Donatella della Porta, Joseba Fernandez, Hara Kouki and Lorenzo Mosca, Movement Parties Against Austerity. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2017.

- ↑ G. John Ikenberry, After Victory: Institutions, Strategic Restraint, and the Rebuilding of Order After Major Wars. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2001.

- ↑ Claire Dupont, Sebastian Oberthür, and Ingmar von Homeyer, "The Covid-19 Crisis: A Critical Juncture for EU Climate Policy Development? Journal of European Integration Vol. 42, No. 8 (2020) 1095-1110; Duncan Green, "COVID-19 as a Critical Juncture and the Implications for Advocacy," Global Policy April 2020; John Twigg, "COVID-19 as a ‘Critical Juncture’: A Scoping Review." Global Policy December 2020; Special Issue of International Organization, 74(S1)(2020); Donatella della Porta, “Progressive Social Movements, Democracy and the Pandemic,” in Gerard Delanty (ed.), Pandemics, Politics, and Society: Critical Perspectives on the Covid-19 Crisis. Berlin: de Gruyter, 2021.

- ↑ Barrington Moore, Jr., Social Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy. Lord and Peasant in the Making of the Modern World. Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 1966; Theda Skocpol, "A Critical Review of Barrington Moore's Social Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy [Book Review]." Politics and Society 4(1)(1973): 1-34, p. 10.

- ↑ Ruth Berins Collier and David Collier, Shaping the Political Arena: Critical Junctures, the Labor Movement, and the Regime Dynamics in Latin America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1991; Einar Berntzen, “Historical and Longitudinal Analyses,” pp. 390–405, in Dirk Berg-Schlosser, Bertrand Badie, and Leonardo Morlino (eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Political Science. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2020.

- ↑ Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson, Why Nations Fail: Origins of Power, Poverty and Prosperity. New York, NY: Crown, 2012; Jared Diamond, "What Makes Countries Rich or Poor?" [Book review of Why Nations Fail] The New York Review of Books, June 7, 2012.

- ↑ Jonathan Yoe, “Review: State Institutions and Economic Prosperity.” Monthly Labor Review (February 2019): 1-4.

- ↑ Arthur L Stinchcombe, Constructing Social Theories. New York, NY: Harcourt, Brace, and World, 1968, pp. 101–106.

- ↑ Jared Diamond, Guns, Germs and Steel. The Fate of Human Societies. New York, NY: Norton, 1997.

- ↑ Michael Mitterauer, Why Europe? The Medieval Origins of its Special Path. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2010.

- ↑ Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson, Why Nations Fail: Origins of Power, Poverty and Prosperity. New York, NY: Crown, 2012; Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson, The Narrow Corridor. States, Societies, and the Fate of Liberty. New York, NY: Penguin, 2019).

- ↑ Jerry F. Hough and Robin Grier, The Long Process of Development: Building Markets and States in Pre-Industrial England, Spain and their Colonies. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

- ↑ Daron Acemoglu, Simon H. Johnson, and James A. Robinson, “The Colonial Origins of Comparative Development: An Empirical Investigation“ The American Economic Review Vol. 91, No. 5 (2001): 1369-1401, pp. 1369–70; Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson, Why Nations Fail: Origins of Power, Poverty and Prosperity. New York, NY: Crown, 2012; James Mahoney, Colonialism and Postcolonial Development: Spanish America in Comparative Perspective. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2010; Stanley L. Engerman and Kenneth L. Sokoloff, Economic Development in the Americas since 1500: Endowments and Institutions. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

- ↑ Sebastián L. Mazzuca, “Critical Juncture and Legacies: State Formation and Economic Performance in Latin America“ Qualitative & Multi-Method Research Vol. 15, No. 1 (2017): 29-35, p. 34.

- ↑ Rudiger Dornbusch and Sebastián Edwards (eds.), The Macroeconomics of Populism in Latin America. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1991.

- ↑ Atul Kohli, State-Directed Development: Political Power and Industrialization in the Global Periphery. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- ↑ Tuong Vu, Paths to Development in Asia: South Korea, Vietnam, China, and. Indonesia. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

Further reading (on the framework)[edit]

- Arthur, W. Brian (1989). “Competing Technologies, Increasing Returns, and Lock-In by Historical Events.” Economic Journal 99(394): 116–31. [1]

- Berntzen, Einar (2020). “Historical and Longitudinal Analyses,” pp. 390–405, in Dirk Berg-Schlosser, Bertrand Badie, and Leonardo Morlino (eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Political Science. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Capoccia, Giovanni, and R. Daniel Kelemen (2007). “The Study of Critical Junctures: Theory, Narrative, and Counterfactuals in Historical Institutionalism.” World Politics 59(3): 341–69. [2]

- Collier, David, and Gerardo L. Munck (2017). “Building Blocks and Methodological Challenges: A Framework for Studying Critical Junctures.” Qualitative and Multi-Method Research 15(1): 2–9. [3]

- Collier, David, and Gerardo L. Munck (eds.). (2017). “Symposium on Critical Junctures and Historical Legacies.” Qualitative and Multi-Method Research 15(1): 2–47. [4]

- Collier, Ruth Berins, and David Collier (1991). Shaping the Political Arena: Critical Junctures, the Labor Movement, and the Regime Dynamics in Latin America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, Ch. 1: "Framework: Critical Junctures and Historical Legacies." [5]

- David, Paul A. (1985). “Clio and the Economics of QWERTY.” American Economic Review 75(2): 332–37. [6]

- Gerschewski, Johannes. (2021). “Explanations of Institutional Change. Reflecting on a ‘Missing Diagonal’.” American Political Science Review 115(1): 218–33.

- Krasner, Stephen D. (1984). “Approaches to the State: Alternative Conceptions and Historical Dynamics.” Comparative Politics 16(2): 223–46. [7]

- Krasner, Stephen D. (1988). “Sovereignty: An Institutional Perspective.” Comparative Political Studies 21(1): 66–94. [8]

- Mahoney, James (2000). “Path Dependence in Historical Sociology.” Theory and Society 29(4): 507–48. [9]

- Pierson, Paul. (2000). “Increasing Returns, Path Dependence, and the Study of Politics.” American Political Science Review 94(2): 251–67. [10]

- Slater, Dan, and Erica Simmons (2010). “Informative Regress: Critical Antecedents in Comparative Politics.” Comparative Political Studies 43(7): 886-917. [11]

- Soifer, Hillel David (2012). “The Causal Logic of Critical Junctures.” Comparative Political Studies 45(12): 1572-1597. [12]

Further reading (substantive applications)[edit]

- Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson, Why Nations Fail: Origins of Power, Poverty and Prosperity (2012).

- Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson, The Narrow Corridor. States, Societies, and the Fate of Liberty (2019).

- Avidit Acharya, Matthew Blackwell, and Maya Sen, Deep Roots: How Slavery Still Shapes Southern Politics (2018).

- Stefano Bartolini, The Political Mobilization of the European Left, 1860–1980: The Class Cleavage (2000).

- Stefano Bartolini, Restructuring Europe. Centre Formation, System Building, and Political Structuring between the Nation State and the European Union (2007).

- Kent Calder and Min Ye, The Making of Northeast Asia (2010).

- Daniele Caramani, The Europeanization of Politics: The Formation of a European Electorate and Party System in Historical Perspective (2015).

- Donatella della Porta et al., Discursive Turns and Critical Junctures: Debating Citizenship after the Charlie Hebdo Attacks (2020).

- Vivek Chibber, Locked in Place: State-building and Late Industrialization in India (2003).

- Stanley L. Engerman and Kenneth L. Sokoloff, Economic Development in the Americas since 1500: Endowments and Institutions (2012).

- Thomas Ertman, Birth of the Leviathan: Building States and Regimes in Medieval and Early Modern Europe (1997).

- Robert M. Fishman, Democratic Practice: Origins of the Iberian Divide in Political Inclusion (2019).

- Andrew C. Gould, Origins of Liberal Dominance: State, Church, and Party in Nineteenth-Century Europe (1999).

- Anna M. Grzymała-Busse, Redeeming the Communist Past: The Regeneration of Communist Parties in East Central Europe (2002).

- G. John Ikenberry, After Victory: Institutions, Strategic Restraint, and the Rebuilding of Order After Major Wars. (2001).

- Lauri Karvonen and Stein Kuhnle (eds.), Party Systems and Voter Alignments Revisited (2000).

- Marcus Kurtz, Latin American State Building in Comparative Perspective: Social Foundations of Institutional Order (2013).

- Matthew Lange, Lineages of Despotism and Development. British Colonialism and State Power (2009).

- Evan S. Lieberman, Race and Regionalism in the Politics of Taxation in Brazil and South Africa (2003).

- Seymour M. Lipset and Stein Rokkan (eds.), Party Systems and Voter Alignments: Cross-National Perspectives (1967).

- Fernando López-Alves, State Formation and Democracy in Latin America, 1810–1900 (2000).

- Gregory M. Luebbert, Liberalism, Fascism, or Social Democracy: Social Classes and the Political Origins of Regimes in Interwar Europe (1991).

- James Mahoney, The Legacies of Liberalism: Path Dependence and Political Regimes in Central America (2001).

- Jørgen Møller, “Medieval Origins of the Rule of Law: The Gregorian Reforms as Critical Juncture?” Hague Journal on the Rule of Law 9(2)(2017): 265–82.

- Barrington Moore, Jr., Social Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy. Lord and Peasant in the Making of the Modern World (1966).

- Robert D. Putnam, with Robert Leonardi and Raffaella Nanetti, Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy (1993).

- Rachel Beatty Riedl, Authoritarian Origins of Democratic Party Systems in Africa (2014).

- Stein Rokkan with Angus Campbell, Per Torsvik, and Henry Valen, Citizens, Elections, and Parties: Approaches to the Comparative Study of the Processes of Development (1970).

- Kenneth M. Roberts, Changing Course in Latin America: Party Systems in the Neoliberal Era (2014).

- Timothy R. Scully, Rethinking the Center: Party Politics in Nineteenth- and Twentieth-Century Chile (1992).

- Eduardo Silva and Federico M. Rossi (eds.), Reshaping the Political Arena in Latin America (2018).

- Maya Tudor, The Promise of Power: The Origins of Democracy in India and Autocracy in Pakistan (2013).

- Deborah Yashar, Demanding Democracy: Reform and Reaction in Costa Rica and Guatemala, 1870s-1950s (1997).

External Links[edit]

- The Critical Juncture Project, coordinated by David Collier and Gerardo L. Munck [13]

Script error: No such module "AfC submission catcheck".

This article "Critical juncture" is from Wikipedia. The list of its authors can be seen in its historical and/or the page Edithistory:Critical juncture. Articles copied from Draft Namespace on Wikipedia could be seen on the Draft Namespace of Wikipedia and not main one.