Cultural dimensions

Cultural dimensions are statistical constructs which capture the shared variance within sets of variables (typically multi-national survey data) representing cultural values, norms, beliefs and practices organized around a core dichotomy (such as emancipation versus authoritarianism, secularism versus religiosity or progressivism versus conservatism). Cultural dimensions can be created following a confirmatory approach or an exploratory approach. When employing a confirmatory methodology, researchers propose pair of opposed concepts and then measure them across a sample of different cultures. If the scale measuring a given dimension is shown to have internal validity, the cultural dimension becomes accepted as a measure of cultural differences. When employing an exploratory methodology, researchers start from a diverse set of variables measuring cultural values, norms, beliefs and practices. The matrix of variables is subjected to dimension reduction techniques such as exploratory factor analysis (EFA), principal component analysis (PCA) or multidimensional scaling (MDS) in order to uncover latent variables which account for the correlations between the observed variables.

The quantitative study of culture in a global perspective using mathematical models of cultural dimensions started in the early 1980s. Since then, various such models were proposed including those elaborated by Geert Hofstede, Ronald Inglehart, Christian Welzel, the GLOBE project team, Shalom Schwartz and Michael Minkov.

Cultural dimensions models (CDMs)[edit]

A cultural dimension model (CDM) is a theoretical framework aimed at representing the cultural variation found in the contemporary world using a number of latent variables.

Geert Hofstede's CDM[edit]

Geert Hofstede's initial model of national cultures included four dimensions.[1]

Individualism (IDV) – collectivism (COLL) differentiates cultures in which ties between people are flexible and social relationships have a voluntary basis (individualistic cultures) from cultures characterized by strong in-group ties and rigid boundaries between groups (collectivist cultures).[2]

Low power distance (low PD) – high power distance (high PD) refers to the degree of inequalities of authority, prestige and resources that people in various cultures find acceptable. In high power distance cultures, social relationships are based on strict hierarchies in which the superiors enjoy respect and obedience from their subordinates. In low power distance cultures, human relationships are based on the idea that all humans have equal dignity and should respect each other equally.[3]

Low uncertainty avoidance (low UA) – high uncertainty avoidance (high UA) distinguishes between societies in which people deal easily with ambiguity and the unknown from societies in which they favor following precise and predictable routines in order to avoid unexpected or ambiguous situations.[4]

Masculinity (MAS) – femininity (FEM) relates to the orientation of a culture toward assertiveness, competition and achievement (masculinity) respectively modesty as well as warm and nurturing interpersonal relationships (femininity).[5]

Michael Minkov's CDM[edit]

Michael Minkov proposes a four dimension model of the world's cultural variation.

Universalism (UNI) – exclusivism (EXC) distinguishes cultures in which people draw rigid boundaries between in-groups and out-groups from cultures in which they have a similar degree of moral concern for all human beings.[8][9]

Flexibility (FLX) – monumentalism (MON) differentiates societies in which adapting to circumstances and improving one's skills are considered core values from societies in which maintaining stable and persistent traits is viewed to be more important.[10][11]

Hypometropia – prudence refers to the distinction between cultures in which immediate gratification as well as living the present fully is preferred and cultures in which people use to delay gratification and prepare attentively for the long-term.[12]

Industry – indulgence is a dichotomy which relates to the difference between societies where people prioritize hard work and discipline and societies where leisure and subjective well-being are viewed as being more important.[13]

Ronald Inglehart and Wayne Baker's CDM[edit]

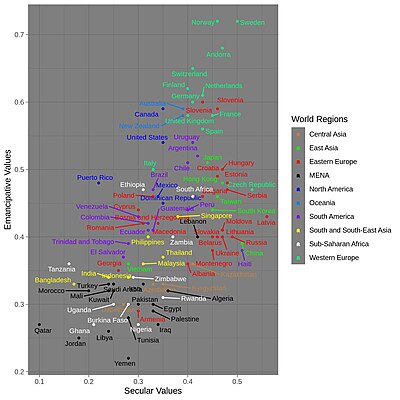

Using data from the World Values Survey, the American political scientist Ronald Inglehart extracted two dimensions of cultural variation.

Traditional versus Secular-Rational Values refers to the contrast between valuing the continuation of ancestral religious and cultural norms (the traditional pole) and valuing rational adaptation to modern conditions (the secular-rational pole).[16]

Survival versus Self-Expression Values is a continuum which differentiates cultures in which the main concern is meeting basic human needs such as (food, shelter, physical safety) and protecting the community from threats to its survival from cultures in which importance is given to a broader range of concerns, including subjective well-being and openness toward diversity of lifestyles.[17]

Shalom H. Schwartz's CDM[edit]

Chinese Culture Connection team's CDM[edit]

The Chinese Culture Connection study was organized by a team of social psychologists from the Chinese University of Hong Kong in order to measure the world's cultures using questionnaires which were inspired by the values promoted by various schools of ancient Chinese philosophy. After subjecting the data to exploratory factor analysis, they uncovered four dimensions of cultural values[18].

Integration is the cultural dimension which contrasts societies in which cohesion is achieved by internalized pro-social motivations centered on tolerance and harmony (high integration) with societies in which cohesion is achieved by external norms which are coercive and constraining toward persons living in those societies (low integration).

Confucian work dynamism refers to the contrast between cultures in which a pragmatic work ethic based on persistence, thrift and order is emphasized (high Confucian work dynamism) and cultures in which respecting traditions and protecting someone's face are seen as more important even when they are in conflict with pragmatic concerns (low Confucian work dynamism).

Human-heartedness is a cultural dimensions which differentiates between societies in which human relationships are based on compassion and empathy (high human-heartedness) from societies in which a harsher and more legalistic approach is adopted (low human-heartedness).

Moral discipline is a continuum ordering cultures according to the degree of importance given to improving one's moral character by having few desires and being moderate (high moral discipline) versus the degree of importance given to adapting to circumstances and preserving oneself even if this means compromising one's moral character.

See also[edit]

Research fields related to the study of cultural dimensions:

- Cross-cultural studies

- Cross-cultural psychology

- Cross-cultural communication

- Cross-cultural leadership

Major contributors to the creation of various cultural dimensions models:

- Christian Welzel

- Geert Hofstede

- Michael Minkov

- Ronald Inglehart

- Shalom H. Schwartz

References[edit]

- ↑ Minkov, Michael; Hofstede, Geert (2011-02-08). "The evolution of Hofstede's doctrine". Cross Cultural Management: An International Journal. 18 (1): 10–20. doi:10.1108/13527601111104269. ISSN 1352-7606.

- ↑ Hofstede, Geert; Hofstede, Jan; Minkov, Michael (2010). "I, We, and They". Cultures and Organizations: Software of The Mind. pp. 89–133 [90–91]. Search this book on

- ↑ Hofstede, Geert; Hofstede, Jan; Minkov, Michael (2010). "Chapter 3. More Equal than Others". Cultures and Organizations: Software of The Mind. pp. 53–86 [54]. Search this book on

- ↑ Geert, Hofstede; Hofstede, Jan; Minkov, Michael (2010). "Chapter 6. What is Different Is Dangerous". Cultures and Organizations: Software of The Mind. pp. 187–233 [188–190]. Search this book on

- ↑ Hofstede, Geert; Hofstede, Jan; Minkov, Michael (2010). "Chapter 5. He, She, and (S)he". Cultures and Organizations: Software of The Mind. pp. 135–184 [136–138]. Search this book on

- ↑ Minkov, Michae l; Dutt, Pinaki; Schachner, Michael; Morales, Oswaldo; Sanchez, Carlos; Jandosova, Janar; Khassenbekov, Yerlan; Mudd, Ben (2017-08-07). "A revision of Hofstede's individualism-collectivism dimension". Cross Cultural & Strategic Management. 24 (3): 386–404. doi:10.1108/ccsm-11-2016-0197. ISSN 2059-5794.

- ↑ Minkov, Michael; Bond, Michael H.; Dutt, Pinaki; Schachner, Michael; Morales, Oswaldo; Sanchez, Carlos; Jandosova, Janar; Khassenbekov, Yerlan; Mudd, Ben (2017-08-29). "A Reconsideration of Hofstede's Fifth Dimension: New Flexibility Versus Monumentalism Data From 54 Countries". Cross-Cultural Research. 52 (3): 309–333. doi:10.1177/1069397117727488. ISSN 1069-3971.

- ↑ Minkov, Michael (2011). "Chapter 6. Exclusionism versus Universalism". Cultural differences in a globalizing world. Emerald Group Publishing. pp. 179–224. Search this book on

- ↑ Minkov, Michae l; Dutt, Pinaki; Schachner, Michael; Morales, Oswaldo; Sanchez, Carlos; Jandosova, Janar; Khassenbekov, Yerlan; Mudd, Ben (2017-08-07). "A revision of Hofstede's individualism-collectivism dimension". Cross Cultural & Strategic Management. 24 (3): 386–404. doi:10.1108/ccsm-11-2016-0197. ISSN 2059-5794.

- ↑ Minkov, Michael (2011). "Chapter 4. Monumentalism versus Flexumility". Cultural differences in a globalizing world. Emerald Group Publishing. pp. 93–135. Search this book on

- ↑ Minkov, Michael; Bond, Michael H.; Dutt, Pinaki; Schachner, Michael; Morales, Oswaldo; Sanchez, Carlos; Jandosova, Janar; Khassenbekov, Yerlan; Mudd, Ben (2017-08-29). "A Reconsideration of Hofstede's Fifth Dimension: New Flexibility Versus Monumentalism Data From 54 Countries". Cross-Cultural Research. 52 (3): 309–333. doi:10.1177/1069397117727488. ISSN 1069-3971.

- ↑ Minkov, Michael (2011). "Chapter 5. Hypometropia versus Prudence". Cultural differences in a globalizing world. Emerald Group Publishing. pp. 137–177. Search this book on

- ↑ Minkov, Michael (2011). "Chapter 3. Industry versus Indulgence". Cultural differences in a globalizing world. Emerald Group Publishing. pp. 51–82. Search this book on

- ↑ Welzel, Christian (2013). "Chapter 2. Mapping Differences". Freedom Rising. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-54091-9. Search this book on

- ↑ "WVS Database". www.worldvaluessurvey.org. Retrieved 2020-07-07.

- ↑ Inglehart, Ronald; Baker, Wayne (2000). "Modernization, cultural change, and the persistence of traditional values". American sociological review: 19–51 [23–24].

- ↑ Inglehart, Ronald; Baker, Wayne (2000). "Modernization, cultural change, and the persistence of traditional values". American sociological review: 19–51 [25–28].

- ↑ Chinese Culture Connection (1987). "Chinese values and the search for culture-free dimensions of culture". Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology: 143–164 [149–151].

This article "Cultural dimensions" is from Wikipedia. The list of its authors can be seen in its historical and/or the page Edithistory:Cultural dimensions. Articles copied from Draft Namespace on Wikipedia could be seen on the Draft Namespace of Wikipedia and not main one.