Dirty subsidy

A dirty subsidy is a payment or incentive by a government to a private corporation (or another level of government) that encourages waste of raw materials, natural resources, or energy, or results in pollution or other human health hazards.

Green economics often focuses on the impact of eliminating such subsidies, and implementing what is sometimes called full-cost accounting. Under full-cost accounting, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimates that, combining the costs of pollution, climate change, and pecuniary expenditures, support for fossil fuels totals about $5.3 trillion a year.[1] Green politics focuses on actually eliminating the subsidies by seeking change to agricultural policy and industrial policy, as well as tax, tariff and trade rules that favor imports from jurisdictions that offer such subsidies. The most widely implemented and discussed dirty subsidies are fossil fuel subsidies.

Effects[edit]

The immediate effect of high fossil fuel subsidies is to decrease the price consumers pay for fuel. Consequently, consumers are not incentivized to pursue energy saving behaviors, either by reducing energy usage or seeking more energy-efficient technologies. This results in increased consumption of fossil fuels as well as increases in the associated negative externalities. Notably, fossil fuel usage generates adverse health effects through air pollution as well as negative impacts on the environment through greenhouse gas emissions, which accelerate climate change.[2] In addition to encouraging greater consumption of fossil fuels, fossil fuel subsidies have the supply-side effects of discouraging investment in energy efficient products and reducing competition in the energy industry.[3]

Fossil fuel subsidies also represent an opportunity cost to the government. The price of the subsidy creates a burden on government budgets which crowds out public spending in other sectors, like education.

However, fossil fuel subsidies allow governments to provide energy inexpensively to ensure that in order to protect poor consumers. Fossil fuel subsidies may disproportionately benefit high and middle income households, who, on average, consume more energy.[4] In this case energy subsidies are likely an inefficient policy for poverty reduction. On a national level, there is concern that consumers developing countries need access to affordable energy encourage economic growth and increase standards of living. In a 2010 opinion piece published in the Washington Post, Pravin Gordhan, South Africa's former Minister of Finance, wrote: "To sustain the growth rates we need to create jobs, we have no choice but to build new generating capacity -- relying on what, for now, remains our most abundant and affordable energy source: coal."[5]

Elimination of Dirty Subsidies[edit]

Impact on Fossil Fuel Consumption and CO2 Emissions[edit]

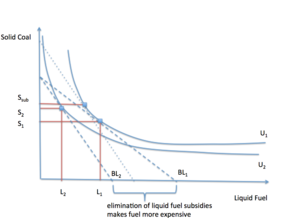

There has been significant empirical work conducted in order to anticipate the effects of phasing out dirty subsidies. Research shows that the long-run price elasticity of demand for diesel and gasoline are more than three times the short-run values, which themselves are non-negligible in countries with high energy subsidies. This indicates that fossil fuel reforms are likely to significantly reduce consumption of fossil fuels in both the short-run and the long-run, which in turn will reduce CO2 emissions.[6] However, other another study shows that long-term gains are likely to be minimal with extraction of fossil resources reduced by no more than 5% by 2100, even if subsidies are completely removed.[7] Rather than prompting a switch to clean energies, it is possible that phasing out fossil fuel subsidies could lead to a substitution effect towards solid fuels, like solid coal, which are not subsidized as heavily as oil and gas, and would become relatively cheaper with the elimination of such subsidies. Moreover, as producers substitute away from using liquid coal, more coal will become available for use in solid coal technologies, thus decreasing the cost of solid fuel.

Economic Impacts[edit]

Empirical studies show that when a country initially subsidizes its fossil fuels, and then eliminates or reduces these subsidies, it experiences higher economic gross domestic product per capita growth, employment, and labor force participation, especially among the youth. These effects are strongest in countries where fuel subsidies are high, such as those in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region.[8] Another study shows that phasing out subsidies is likely to increase consumption in developing regions that import fossil fuels, such as India, China, and Sub-Saharan Africa, but exporting regions like MENA and Russia might not see the same benefits.[7] Additionally, there are fiscal benefits associated with the increase in price.[9]

In Policy[edit]

Many developing countries, particularly in the MENA, subsidize fossil fuels substantially,[6] while the United States spent an average of $20.5 billion a year on gas, oil, and coal subsidies in 2015 and 2016.[10] However, with rising concern about greenhouse gas emissions, pollution, and climate change, governments are facing pressure to encourage clean energy alternatives by phasing out dirty subsidies At the 2009 G20 Pittsburgh Summit, committed to “rationalize and phase out over the medium term inefficient fossil fuel subsidies that encourage wasteful consumption."[4] However, the G20 countries did not commit to a timeline at the time of this declaration. In 2016, the G7 nations announced a deadline to end "inefficient fossil fuel subsidies" of coal, oil, and gas by 2025, where the word "inefficient" characterizes any subsidy that distorts energy markets.[1]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Mathiesen, Karl (2016-05-27). "G7 nations pledge to end fossil fuel subsidies by 2025". the Guardian. Retrieved 2018-03-07.

- ↑ Whitley S. and van der Burg, L. (2015). "Fossil Fuel Subsidy Reform in Sub-Saharan Africa: From Rhetoric to Reality". The New Climate Economy.

- ↑ H., Parry, Ian W. (2014). Getting Energy Prices Right. Heine, Dirk., Lis, Eliza., Li, Shanjun. Washington: International Monetary Fund. ISBN 9781484388570. OCLC 886114795. Search this book on

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 G20 (2011). "Joint report by IEA, OPEC, OECD and World Bank on fossil-fuel and other energy subsidies: An update of the G20 Pittsburgh and Toronto Commitments" (PDF). Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development.

- ↑ Gordhan, Pravin (2010-03-22). "Pravin Gordhan - Why coal is the best way to power South Africa's growth". ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2018-03-03.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Mundaca, Gabriela. "How much can CO 2 emissions be reduced if fossil fuel subsidies are removed?". Energy Economics. 64: 91–104. doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2017.03.014.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Schwanitz, Valeria Jana; Piontek, Franziska; Bertram, Christoph; Luderer, Gunnar. "Long-term climate policy implications of phasing out fossil fuel subsidies". Energy Policy. 67: 882–894. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2013.12.015.

- ↑ Mundaca, Gabriela. "Energy subsidies, public investment and endogenous growth". Energy Policy. 110: 693–709. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2017.08.049.

- ↑ Coady, David; Parry, Ian; Sears, Louis; Shang, Baoping. "How Large Are Global Fossil Fuel Subsidies?". World Development. 91: 11–27. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2016.10.004.

- ↑ Redman, Janet (2017). "Dirty Energy Dominance: Dependent on Denial" (PDF). Oil Change International. Retrieved March 2, 2018.

This article "Dirty subsidy" is from Wikipedia. The list of its authors can be seen in its historical and/or the page Edithistory:Dirty subsidy. Articles copied from Draft Namespace on Wikipedia could be seen on the Draft Namespace of Wikipedia and not main one.