Knowledge in Islam

| Part of a series on |

| Islam |

|---|

|

|

|

In Islam, ʿIlm (Arabic: علم, knowledge) is given great significance. Al-ʿAlīm ("The Knowing") is one of the 99 names reflecting distinct attributes of God. The Qur'an asserts that knowledge comes from God [1] and various hadith encourage the acquisition of knowledge. The Islamic prophet Muhammad is reported to have said "Seek knowledge from the cradle to the grave" and "Verily the men of knowledge are the inheritors of the prophets". Islamic scholars, theologians and jurists are often given the title alim, meaning "knowledgeble".[2]

Overview[edit]

Knowledge is a familiarity, awareness, or understanding of someone or something, such as facts (descriptive knowledge), skills (procedural knowledge), or objects (acquaintance knowledge). In general Islamic terminology, knowledge or 'Ilm is the perception of the true state of an object. On the other hand, Islam meansobedience and obedience. Islamic law and rituals cannot be known without knowledge. Therefore, the importance of knowledge in Islam is immense.

In a Muslim context, Islamic knowledge ('Ilm al-islam) is the umbrella term for the Islamic sciences (Ulum al-din), i.e. the traditional forms of religious knowledge and thought. These include kalam (Islamic theology) (علم الكلام) In Arabic, the word means "discussion" and refers to the Islamic tradition of seeking theological principles through dialectic; A scholar of kalam is referred to as a mutakallim; fiqh (Islamic jurisprudence), Uṣūl al-Fiqh (methodology/principles of Jurisprudence), ḥadīth (traditions), ʿulūm al-ḥadīth (hadith criticism) naskh or al-nāsikh waʾl-mansūkh (abrogations), Usul al-Din (theology), Asma’ al-Rijal (biographies of Hadith scholars), Sirah (Biography (of the Prophet) and Maghazi (Battles of the Prophet).[3] (Studied in institutions in the Muslim world[4]

A subset of the Islamic sciences are `Ulum ul-Qur'an, (the sciences of the Quran). These include "how, where and when the Quran was revealed", and its transformation from an oral tradition to the written form, etc.,[5] and Ilm ul-Tajwid (proper recitation), Ilm ul-Tafsir (exegesis of the Quran),[5] Qiraat (methods of recitation of the Qur’an).[6] (In this context "science" is the translation of the Arabic term for "knowledge, learning, lore," etc.,[7] rather than "science" or natural science as commonly defined in English and other languages[8]—i.e. the use of observation, testable explanations to build and organize knowledge and predictions about the natural world/universe.[9][10][11] It is not to be confused with the scientific work of Muslims such as Avicenna or Nasir al-Din al-Tusi.)

Education would begin at a young age with study of Arabic and the Quran, either at home or in a primary school, which was often attached to a mosque.[12] Some students would then proceed to training in tafsir (Quranic exegesis) and fiqh (Islamic jurisprudence), which was seen as particularly important.[12] Education focused on memorization, but also trained the more advanced students to participate as readers and writers in the tradition of commentary on the studied texts.[12] It also involved a process of socialization of aspiring scholars, who came from virtually all social backgrounds, into the ranks of the ulema.[12]

The religious sciences/Islamic studies "within Islamic civilization, ... began to take their present shape and to develop within competing schools to form a literary tradition in Middle Arabic" in Iraq in the ninth century CE, according to Oxford Islamic Studies.[13]

History[edit]

The first institute of islamic knowledge and education was at the estate of Zaid bin Arkam near a hill called Safa, where Muhammad was the teacher and the students were some of his followers.[citation needed] After Hijrah (migration) the madrasa of "Suffa" was established in Madina on the east side of the Al-Masjid an-Nabawi mosque. Ubada ibn as-Samit was appointed there by Muhammad as teacher and among the students.[citation needed] In the curriculum of the madrasa, there were teachings of The Qur'an, The Hadith, fara'iz, tajweed, genealogy, treatises of first aid, etc. There was also training in horse-riding, the art of war, handwriting and calligraphy, athletics and martial arts. The first part of madrasa-based education is estimated from the first day of "nabuwwat" to the first portion of the Umayyad Caliphate.[citation needed] At the beginning of the Caliphate period, the reliance on courts initially confined sponsorship and scholarly activities to major centres.[citation needed]

During the 6th and 7th centuries, the Academy of Gundishapur, originally the intellectual center of the Sassanid Empire and subsequently a Muslim centre of learning, offered training in medicine, philosophy, theology and science. The faculty were versed not only in the Zoroastrian and Persian traditions, but in Greek and Indian learning as well.

The University of al-Qarawiyyin located in Fes, Morocco is the oldest existing, continually operating and the first degree awarding educational institution in the world according to UNESCO and Guinness World Records[14] and is sometimes referred to as the oldest university.[15]

The House of Wisdom in Baghdad was a library, translation and educational centre from the 9th to 13th centuries. Works on astrology, mathematics, agriculture, medicine, and philosophy were translated. Drawing on Persian, Indian and Greek texts—including those of Pythagoras, Plato, Aristotle, Hippocrates, Euclid, Plotinus, Galen, Sushruta, Charaka, Aryabhata and Brahmagupta—the scholars accumulated a great collection of knowledge in the world, and built on it through their own discoveries. The House was an unrivalled centre for the study of humanities and for sciences, including mathematics, astronomy, medicine, chemistry, zoology and geography. Baghdad was known as the world's richest city and centre for intellectual development of the time, and had a population of over a million, the largest in its time.[16]

In the early history of the Islamic period, teaching was generally carried out in mosques rather than in separate specialized institutions. Although some major early mosques like the Great Mosque of Damascus or the Mosque of Amr ibn al-As in Cairo had separate rooms which were devoted to teaching, this distinction between "mosque" and "madrasa" was not very present.[17] [18][19] According to tradition, the al-Qarawiyyin mosque was founded by Fāṭimah al-Fihrī, the daughter of a wealthy merchant named Muḥammad al-Fihrī. This was later followed by the Fatimid establishment of al-Azhar Mosque in 969–970 in Cairo, initially as a center to promote Isma'ili teachings, which later became a Sunni institution under Ayyubid rule (today's Al-Azhar University).[20][21][22][23]

The traditional islamic institutions likely came up in Khurasan during the 10th century AD, and spread to other parts of the Islamic world from the late 11th century onwards.[24] The most famous early madrasas are the Sunni Niẓāmiyya, founded by the Seljuk vizir Nizam al-Mulk (1018–1092) in Iran and Iraq in the 11th century. The Mustansiriya, established by the Abbasid caliph Al-Mustansir in Baghdad in 1234 AD, was the first to be founded by a caliph, and also the first known to host teachers of all four major madhhab known at that time. From the time of the Persian Ilkhanate (1260–1335 AD) and the Timurid dynasty (1370–1507 AD) onwards, madrasas often became part of an architectural complex which also included a mosque, a Sufi ṭarīqa, and other buildings of socio-cultural function, like baths or a hospital.[24]

Importance[edit]

The importance of knowledge in Islam is so important that God has initiated the revelation of the Holy Quran by word Iqra (read).[25][26][27][28][29][30][31]

- "Read! in the name of your Lord who created

- Man from a clinging substance.

- Read: Your Lord is most Generous,–

- He who taught by the pen–

- Taught man that which he knew not."[Quran 96:1–5] (First five ayahs of Al-Alaq)

Therefore, the practice of knowledge is essential for the development of humanity and the development of a perfect human being through the acquisition of knowledge through reading. The wise and the ignorant can never be equal.

"God raises those who believed among you, and those who have learned knowledge have relented." [Surat Al-Mujadila, verse 11][32]

Islam has made the acquisition of knowledge obligatory on all Muslims. Muhammad said:

Seeking knowledge is an obligation for every Muslim [Ibn Majah][citation needed]

Elsewhere, Muhammad called the acquisition of knowledge a good act of worship.

Typology[edit]

There are many branches of knowledge in Islam. In Islam, two types of knowledge is existed- Religious knowledge ( 'Ilm al-din) and worldly knowledge ( 'Ilm al-dunya).

Religious knowledge usually refers to the knowledge of Islam. Such as- knowledge of Quran, Hadith, Fiqh, Tafsir etc. And worldly knowledge means only the knowledge associated with worldly progress. Such as- knowledge of mathematics, science, geography, literature, physics, chemistry etc. Sharia has divided knowledge into another two parts Acceptable knowledge and excluded knowledge. Acceptable knowledge is that knowledge comes to the welfare of man in this world and in the hereafter. For example: moral knowledge, medical science, engineering, physics, chemistry and all beneficial knowledge. And the excluded knowledge is that knowledge does not come to any good of man but by which evil isachieved in this world and in the hereafter. Such as gaining knowledge about immoral knowledge, theft, robbery, injustice, oppression, militancy and terrorism.

Purpose[edit]

According to Islam, every Muslim must have a basic knowledge of Islam. However, a group from every community or country must be a scholar of Islam, otherwise all must givean explanation to God in the Hereafter. God says in Quran,

"If it were not approved by each group of them, they would agree on figs and vow their people if they returned to them." [Surat

Islam claims that the purpose of Islam is to do good to the people. As Muhammad said,

"Religion (Islam) is to do good." [Muslim][citation needed]

Sources[edit]

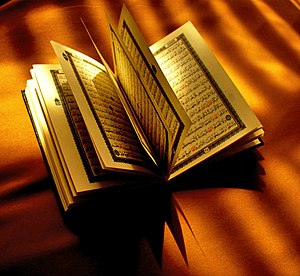

Qur’an[edit]

The Qur'an is the first and most important source of Islamic law and also the Islamic knowledge. Believed to be the direct word of God as revealed to Muhammad through angel Gabriel in Mecca and Medina, the scripture specifies the moral, philosophical, social, political and economic basis on which a society should be constructed. The verses revealed in Mecca deal with philosophical and theological issues, whereas those revealed in Medina are concerned with socio-economic laws. The Qur'an was written and preserved during the life of Muhammad, and compiled soon after his death.[34]

The verses of the Qur'an are categorized into three fields: "science of speculative theology", "ethical principles" and "rules of human conduct". The third category is directly concerned with Islamic legal matters which contains about five hundred verses or one thirteenth of it. The task of interpreting the Qur'an has led to various opinions and judgments. The interpretations of the verses by Muhammad's companions for Sunnis and Imams for Shias are considered the most authentic, since they knew why, where and on what occasion each verse was revealed.[35][34]

Sunnah[edit]

The Sunnah is the next important source, and is commonly defined as "the traditions and customs of Muhammad" or "the words, actions and silent assertions of him". It includes the everyday sayings and utterances of Muhammad, his acts, his tacit consent, and acknowledgments of statements and activities. According to Shi'ite jurists, the sunnah also includes the words, deeds and acknowledgments of the twelve Imams and Fatimah, Muhammad's daughter, who are believed to be infallible.[35][36]

Justification for using the Sunnah as a source of law can be found in the Qur'an. The Qur'an commands Muslims to follow Muhammad.[37] During his lifetime, Muhammad made it clear that his traditions (along with the Qur'an) should be followed after his death.[38] The overwhelming majority of Muslims consider the sunnah to be essential supplements to and clarifications of the Qur'an. In Islamic jurisprudence, the Qur'an contains many rules for the behavior expected of Muslims but there are no specific Qur'anic rules on many religious and practical matters. Muslims believe that they can look at the way of life, or sunnah, of Muhammad and his companions to discover what to imitate and what to avoid.

Hadith[edit]

Much of the sunnah is recorded in the Hadith. Initially, Muhammad had instructed his followers not to write down his acts, so they may not confuse it with the Qur'an. However, he did ask his followers to disseminate his sayings orally. As long as he was alive, any doubtful record could be confirmed as true or false by simply asking him. His death, however, gave rise to confusion over Muhammad's conduct. Thus the Hadith were established.[36] Due to problems of authenticity, the science of Hadith (Arabic: 'Ulum al-hadith) is established. It is a method of textual criticism developed by early Muslim scholars in determining the veracity of reports attributed to Muhammad. This is achieved by analyzing the text of the report, the scale of the report's transmission, the routes through which the report was transmitted, and the individual narrators involved in its transmission. On the basis of these criteria, various Hadith classifications developed.[39]

To establish the authenticity of a particular Hadith or report, it had to be checked by following the chain of transmission (isnad). Thus the reporters had to cite their reference, and their reference's reference all the way back to Muhammad. All the references in the chain had to have a reputation for honesty and possessing a good retentive memory.[36] Thus biographical analysis ('ilm al-rijāl, lit. "science of people"), which contains details about the transmitter are scrutinized. This includes analyzing their date and place of birth; familial connections; teachers and students; religiosity; moral behaviour; literary output; their travels; as well as their date of death. Based upon these criteria, the reliability (thiqāt) of the transmitter is assessed. Also determined is whether the individual was actually able to transmit the report, which is deduced from their contemporaneity and geographical proximity with the other transmitters in the chain.[40] Examples of biographical dictionaries include Ibn Hajar al-Asqalani's "Tahdhīb al-Tahdhīb" or al-Dhahabi's "Tadhkirat al-huffāz."[41]

Using this criterion, Hadith are classified into three categories:[36]

- Undubitable (mutawatir), which are very widely known, and backed up by numerous references.

- Widespread (mashhur), which are widely known, but backed up with few original references.

- Isolated or Single (wahid), which are backed up by too few and often discontinuous references.

Place of knowledge[edit]

The traditional islamic place of higher education and knowledge was the madrassah. Madrasas were merely (sacred) places of learning. They provided boarding and salaries to a limited number of teachers, and boarding for a number of students out of the revenue from religious endowments (waqf), allocated to a specific institution by the donor. In later times, the deeds of endowment were issued in elaborate Islamic calligraphy, as is the case for Ottoman endowment books (vakıf-name).[42] The donor could also specify the subjects to be taught, the qualification of the teachers, or which madhhab the teaching should follow.[24] However, the donor was free to specify in detail the curriculum, as was shown by Ahmed and Filipovic (2004) for the Ottoman imperial madrasas founded by Suleiman the Magnificent.[43]

As Berkey (1992) has described in detail for the education in medieval Cairo, unlike medieval Western universities, in general madrasas had no distinct curriculum, and did not issue diplomas.[44] The educational activities of the madrasas focused on the law, but also included what Zaman (2010) called "Sharia sciences" (al-ʿulūm al-naqliyya) as well as the rational sciences like philosophy, astronomy, mathematics or medicine. The inclusion of these sciences sometimes reflect the personal interests of their donors, but also indicate that scholars often studied various different sciences.[24]

Maktab[edit]

Maktab (Arabic: مكتب) is used primarily in Dari Persian in Afghanistan as an equivalent term to school, including both primary and secondary schools. Kuttab in Afghanistan refers to only elementary schools.

The famous Persian Islamic philosopher and teacher, Ibn Sina (known as Avicenna in the West) used the word maktab in the same sense. In the 11th century, in one of his books, he wrote a chapter dealing with the maktab entitled "The Role of the Teacher in the Training and Upbringing of Children", as a guide to teachers working at maktab schools. He wrote that children can learn better if taught in classes instead of individual tuition from private tutors, and he gave a number of reasons for why this is the case, citing the value of competition and emulation among pupils as well as the usefulness of group discussions and debates. Ibn Sina described the curriculum of a maktab school in some detail, describing the curricula for two stages of education in a maktab school.[45] Ibn Sina (Avicenna) wrote that children should be sent to a maktab school from the age of 6 and be taught primary education until they reach the age of 14.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ↑ [Quran 2:239]

- ↑ "Alim". Lexico. Oxford. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- ↑ Beg, Muhammad Abdul Jabbar (30 August 2010). "The Origins of Islamic Science. 2.3. Unity of Knowledge: Religious, Rational and Experimental". Muslimheritage. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

- ↑ such as "Faculty of Islamic Sciences". Ankara Yildirim Beyazit University. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Ayatullah Jafar Subhani (2005). "Foreword". Introduction to the Science of Tafsir of the Quran. Lulu Press, Inc. ISBN 9781312537460. Retrieved 28 November 2019. Search this book on

- ↑ Salahi, Adil (16 July 2001). "Scholar Of Renown: Ibn Mujahid". Arab News. Retrieved 26 March 2021.

- ↑ https://giftsofknowledge.files.wordpress.com/2016/01/hans-wehr-searchable-pdf.pdf Searcheable PDF of the Hans Wehr Dictionary

- ↑ Huff, Toby (2007). Islam and Science. Armonk, Ny: M.E. Sharpe, Inc. pp. 26–36. ISBN 978-0-7656-8064-8. Search this book on

- ↑ Wilson, E.O. (1999). "The natural sciences". Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge (Reprint ed.). New York, New York: Vintage. pp. 49–71. ISBN 978-0-679-76867-8. Search this book on

- ↑ "... modern science is a discovery as well as an invention. It was a discovery that nature generally acts regularly enough to be described by laws and even by mathematics; and required invention to devise the techniques, abstractions, apparatus, and organization for exhibiting the regularities and securing their law-like descriptions."— p.vii Heilbron, J.L. (editor-in-chief) (2003). "Preface". The Oxford Companion to the History of Modern Science. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. vii–X. ISBN 978-0-19-511229-0. Search this book on

- ↑ "science". Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. Merriam-Webster, Inc. Retrieved October 16, 2011.

3 a: knowledge or a system of knowledge covering general truths or the operation of general laws especially as obtained and tested through scientific method b: such knowledge or such a system of knowledge concerned with the physical world and its phenomena.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 Jonathan Berkey (2004). "Education". In Richard C. Martin. Encyclopedia of Islam and the Muslim World. MacMillan Reference USA.

- ↑ "Islamic Studies". Oxford Islamic Studies. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

- ↑ "Oldest higher-learning institution, oldest university".

- ↑ Verger, Jacques: "Patterns", in: Ridder-Symoens, Hilde de (ed.): A History of the University in Europe. Vol. I: Universities in the Middle Ages, Cambridge University Press, 2003, ISBN 978-0-521-54113-8 Search this book on

., pp. 35–76 (35)

., pp. 35–76 (35)

- ↑ George Modelski, World Cities: –3000 to 2000, Washington DC: FAROS 2000, 2003. ISBN 978-0-9676230-1-6 Search this book on

.. See also Evolutionary World Politics Homepage. Archived 28 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine

.. See also Evolutionary World Politics Homepage. Archived 28 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Pedersen, J.; Makdisi, G.; Rahman, Munibur; Hillenbrand, R. (2012). "Madrasa". Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Brill. Search this book on

- ↑ Makdisi, George: "Madrasa and University in the Middle Ages", Studia Islamica, No. 32 (1970), pp. 255–264

- ↑ Verger, Jacques: "Patterns", in: Ridder-Symoens, Hilde de (ed.): A History of the University in Europe. Vol. I: Universities in the Middle Ages, Cambridge University Press, 2003, ISBN 978-0-521-54113-8 Search this book on

., pp. 35–76 (35):

., pp. 35–76 (35): No one today would dispute the fact that universities, in the sense in which the term is now generally understood, were a creation of the Middle Ages, appearing for the first time between the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. It is no doubt true that other civilizations, prior to, or wholly alien to, the medieval West, such as the Roman Empire, Byzantium, Islam, or China, were familiar with forms of higher education which a number of historians, for the sake of convenience, have sometimes described as universities.Yet a closer look makes it plain that the institutional reality was altogether different and, no matter what has been said on the subject, there is no real link such as would justify us in associating them with medieval universities in the West. Until there is definite proof to the contrary, these latter must be regarded as the sole source of the model which gradually spread through the whole of Europe and then to the whole world. We are therefore concerned with what is indisputably an original institution, which can only be defined in terms of a historical analysis of its emergence and its mode of operation in concrete circumstances.

- ↑ Creswell, K.A.C. (1952). The Muslim Architecture of Egypt I, Ikhshids and Fatimids, A.D. 939–1171. Clarendon Press. p. 36. Search this book on

- ↑ Brett, Michael (2017). The Fatimid Empire. Edinburgh University Press. p. 104. Search this book on

- ↑ Behrens-Abouseif, Doris (1989). Islamic Architecture in Cairo: an Introduction. E.J. Brill. pp. 58–62. Search this book on

- ↑ Jonathan Berkey, The Transmission of Knowledge in Medieval Cairo (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1992), passim

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 Zaman, Muhammad Qasim (2010). Cook, Michael, ed. Transmitters of authority and ideas across cultural boundaries, eleventh to eighteenth century. In: The new Cambridge history of Islam (3rd ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 600–603. ISBN 978-0-521-51536-8. Search this book on

- ↑ Muhammad Mustafa Al-A'zami (2003), The History of The Qur'anic Text: From Revelation to Compilation: A Comparative Study with the Old and New Testaments, pp. 25, 47–8. UK Islamic Academy. ISBN 978-1872531656 Search this book on

..

..

- ↑ Brown (2003), pp. 72–3.

- ↑ Sell (1913), p. 29.

- ↑ Bukhari volume 1, book 1, number 3

- ↑ Sahih al-Bukhari 3392; In-book reference: Book 60, Hadith 66l USC-MSA web (English) reference: Vol. 4, Book 55, Hadith 605.

- ↑ Sahih Muslim 160 a; In-book reference: Book 1, Hadith 310; USC-MSA web (English) reference: Book 1, Hadith 301.

- ↑ Ibn Ishaq, Sirat Rasul Allah, p. 106.

- ↑ [Quran 11:58]

- ↑ [Quran 9:122]

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Nomani and Rahnema (1994), pp. 3–4

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedJurisprudence - ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 36.3 Nomani and Rahnema (1994), pp. 4–7

- ↑ Quran 59:7

- ↑ Qadri (1986), p. 191

- ↑ "Hadith", Encyclopedia of Islam.

- ↑ Berg (2000) p. 8

- ↑ See:

- Robinson (2003) pp. 69–70;

- Lucas (2004) p. 15

- ↑ J. M. Rogers (1995). Religious endowments. In: Empire of the Sultans. Ottoman art from the collection of Nasser D. Khalili. London: Azimuth Editions/The Noor Foundation. pp. 82–91. ISBN 978-2-8306-0120-6. Search this book on

- ↑ Ahmed, Shabab; Filipovich, Nenad (2004). "The sultan's syllabus: A curriculum for the Ottoman imperial medreses prescribed in a ferman of Qanuni I Süleyman, dated 973 (1565)". Studia Islamica. 98 (9): 183–218.

- ↑ Jonathan Berkey (1992). The transmission of knowledge in medieval Cairo: A social history of Islamic education. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. pp. 44–94. ISBN 978-0-691-63552-1. JSTOR j.ctt7zvxj4. Search this book on

- ↑ M. S. Asimov, Clifford Edmund Bosworth (1999), The Age of Achievement: Vol 4, Motilal Banarsidass, pp. 33–4, ISBN 81-208-1596-3

This article "Knowledge in Islam" is from Wikipedia. The list of its authors can be seen in its historical and/or the page Edithistory:Knowledge in Islam. Articles copied from Draft Namespace on Wikipedia could be seen on the Draft Namespace of Wikipedia and not main one.