Literary hope theory

Literary hope theory is a framework for the critical analysis of hope and despair as themes in literature. This approach to literary criticism concerns itself with the viability, validity, and verity of hope, or the lack thereof, on the individual, societal, and global level. For this reason, literary hope theory questions whether hope is a reasonable mindset or emotion, and whether people are entitled to experience it, given all the problems of the world, and humanity's role in creating or exacerbating them. Some perspectives view hope as a natural, healthy reaction to anxieties about the future, others view it as a product of privilege and ignorance, and still others view it as a moral imperative for the betterment of the world.

Narratives of hope and despair often fall somewhere on a spectrum of perspectives. On one end of the spectrum is optimistic perception of hope in literature, which emphasizes a reason for empowerment and courage, as well as a pride in the strength and endurance of the human spirit. This perspective is often criticized, justly or unjustly, for its promotion of naivety, delusional insistence on forgoing facts and logic, and encouragement of blind trust in a hopeful future which results in ignorant complacency. On the other hand, pessimistic interpretations regarding narratives of hope define themselves as being disillusioned with the world, negative, but knowing, and unduped. Pessimistic perceptions of literature often depict suffering as pain without deeper meaning or greater purpose, without silver lining. However, while negative interpretations of circumstances are typically seen as more realistic and factual, which is still a matter of debate, they often lead to a greater sense that the world is inherently broken, and that nothing can or will be done to fix it. This defeatism can create a parallel kind of complacency to that which false hope creates, leading to a collective unconsciousness of learned helplessness and doomer ideology. Since both these positions rely on consistent interpretations of all events in only one light, they are often biast towards a certain perspective, resulting in arguments which may constitute logical fallacies or lapses in reason. Despite this, they are useful foundations for the creation of opposing perspectives in literary hope theory, and therefore a prospective synthesis of ideas. That said, optimistic nor pessimistic perceptions of hope are factually "wrong" since evaluations of these approaches can never be fully objective, or take into account a scope of existence large enough to assess cumulatively.

While literary hope theory can be applied to virtually any text, fiction or nonfiction, it is especially prevalent in narratives depicting visions of possible futures, either in utopias (idealistically perfect societies) or dystopias (structurally corrupt societies). The ways in which authors predict or warn against future dystopias can reflect on an increasing dread related to climate change anxiety, inequality frustration, and other barriers to world progress. Utopian studies can also be considered alongside film studies in order to create an interdisciplinary analysis of the ways in which hope progresses and adapts in different mediums, such as book-to-film adaptations, and why that may be. Literary hope theory also interacts with ideologies of fate and free will, and how either framework may create a theme of hope or despair under different interpretations. Whether a narrative maintains or disintegrates the set status quo is also a topic of interest for this field of study, impacting perceptions of defeatism, control, and power for the individual and the collective. On a meta-textual level, literary hope theory turns its criticism inward, and asks: how useful are narratives of hope or despair to society? Do they breed ideologies of apathy and complacency? Do they help individuals gain knowledge, understanding, and agency, and, if so, is that enough? Can reading be sufficient activism, or are we under an ethical obligations to do more? If we must do more, can any action taken by any individual or collective ever truly be enough?

Optimistic perception in literature[edit]

Empowerment and courage[edit]

As we know, empowerment and courage are two keywords related to hope, one of the main themes in literary works. Many texts related to hope utilize the empowerment of women to give hope for women and show them that they can in fact be in power. In addition, empowerment may be related to other things and it can show us individuals that we can be in control. This sense of empowerment provides hopes for the readers who are reading texts exhibiting hope. In addition, courage shows us that people must be brave and try new things, this way, they will have hope that they can achieve anything by being courageous. Being courage requires us to try things even if they make us uncomfortable. Being able to be courage and get out of our comfort zone to achieve something gives us hope that we can achieve it. Empowering individuals and making them feel that they have some sense of control and power gives them hope for later and shows them that they can have power and strength. In order to be in power and feel hopeful that we can achieve our goals, we must be brave and have some courage. Without courage, which is the ability to do something that scares us, we won't be able to feel hopeful that we can be in power and have our voice be heard. Empowerment and courage are linked together, especially when it comes to the literary hope theory. We must be hopeful that we can get to our goal and be empowered and have control. It is not possible to get there without bravery and courage. Thus, when discussing hope in literature, we must think of empowerment of others and the courage choices they must make in order to achieve hope.[1] In order to achieve hope, we must have the courage to ask, to take action, and to speak up.[2] The mistakes that we do will turn into an empowering tool after we learn from them and after we learn what is right and what is wrong. By learning from our mistakes, we will be empowered that we will not make them again and we will achieve hope and an optimistic perception.[3] In almost all the texts that have the literary hope theme and that may analyzed using literary hope theory, we have a sense of empowerment and courage used to get there. Without courage and empowerment, we do not have hope or an optimistic perception. It is not always clear where hope comes from or what it will achieve, but when we have empowerment and courage, they give us some hope that good things still exist and that hope is still found somewhere. Therefore, empowerment also known as authorization, and courage are two significant elements when it comes to literary hope.

The concept of a utopia[edit]

To begin with, utopia is the facile synonym for the purest fancy.[4] Utopia gives us a sense of power and hope. It is an imagined place where everything is supposedly perfect, as opposed to dystopia. It simply refers to a good place.[4] Without utopia, we would be individuals without any importance or sense of superiority. When it comes to the theme of hope, the concept of utopia is discussed frequently. The idea and concept of a utopia gives us hope that we can actually achieve a world where everything is not necessarily perfect, but free of suffering and misery. The concept of a utopia automatically provides us with hope that it is not impossible to live a life free or negativity. According to Sargent, the critical dystopia generally includes a utopian enclave or hope that the dystopian conditions can be overcome in favor of a utopia. This shows us that negativity, misery, and suffering can be solved and defeated in support of a utopia.[4] Dystopia may be replaced with a utopia. It is clear that young adult dystopian literature has significantly adapted the adult dystopian genre to include hope. This joint effort to rid the world of its bad influence is one of the chief ways that hope can exist in the text. Together, reader and character will create a new utopia. Obviously, this is a strategy L'Engle uses to promote hope in the dystopian world. Hope is figured in the young adult protagonist who can defeat dystopia.[5] In a number of classic tales, the child or young adult is the utopia in the dystopian world. Therefore, the concept of utopia is heavily liked to the literary hope theory since it provides us a sense of hope that we are actually able to achieve a world free of negativity and pessimism. When we think of a world where no negativity takes place, we feel a sense of hope and superiority. We are optimistic and hopeful that we can achieve a utopia, or something similar to it.

Naivety[edit]

Sometimes, being naïve may not help us and might trick us into being hopeful for nothing. Being naïve indicates being guileless and lacking wisdom and judgement. We sometimes see some naïve hopefulness that are found in some literary works related to hope. We sometimes believe that we can fix things when the world is a total mess and that we can turn a world full of misery, torture, and suffering into a world free of problems and negativity. But, this is somehow naivety. It shows that we lack some experience and that we have a little bit too much faith in the future. This naïve hope will not get us anywhere or provide any hope for us. We cannot always act naive and expect a positive outcome in the future and have hope for no apparent reason. The reason there is something called naive hope is because we hope for things that are not possible or that are very far from occurring. In order to be hopeful without being naive, we must be hopeful about something realistic and logical.[6] Naivety often describes a neglect and ignorance of pragmatism in favor of moral idealism. If we want to achieve hope, we must remove naivety and be logical and have experience.

False hope[edit]

False hope is often seen as a negative aspect when it comes to literary hope theory, it has a negative connotation. Having false hope refers to having an expectation or outcome that will most probably not occur. Taking optimism too far can result and lead to false hope. We must have realistic expectations. It is not wrong to be optimistic as long as we are realistic too. Having false hope will lead to disappointment if the expectation is jot reached. Having false hope will lead to discontentedness and dissatisfaction for taking our optimism and expectations too far. This is why we should set realistic expectations and think logically and rationally when it comes to hope. Thus, false hope portrays expectations based on illusions rather than reality.[7] Having too much hope and being too positives usually lead to false hope. True hope is grounded in reality whereas false hope results from significant distortions of reality.[8] Therefore, giving false hope is considered as morally wrong and having false hope results in sadness and disappointed for setting very high expectations.

Pessimistic perception in literature[edit]

Suffering[edit]

Tension is one of the major elements of a narrative, acting as a catalyst for the plot, which must then ascend Freytag's Pyramid, climax, fall, and eventually resolve itself in many texts.[9] This framework has become central to the construction of many works now considered to be in the literary canon, and although Gustav Freytag argued against the necessity for full-fledged or continuous conflict,[9] so has the theme of suffering.[1] In the article "Young Adult Literature: Let It Be Hope", by Kristen Downey Randle, editor Chris Crowe refers to the idolization of suffering in literature as the "Dark is Deep" philosophy.[1] Both Randal and Crowe criticize this approach as a structure for finding insight, understanding, or meaning through literature, especially when it comes to narratives taught to young adults of high school age or younger. Stories offering no hope, stories of despair, or, "bleak" books, are argued to be books of half-truth, concealing the fact that while life does contain pain, it also contains happiness, and, with hard work and a strong moral compass, the hope of a better future and a better world. This interpretation of suffering, as a temporary conflict which eventually inspires confidence in the resilience of the human spirit, is criticized by hopeless thinkers and writers such as Philip Larkin, who believed in the meaningless and destructive nature of life, and who dealt with this knowledge by writing about the only thing life and time could not erase in his view: his failings.[10] In this way, Larkin, as well as other writers of note, such as Sylvia Plath,[11] presented their strength not through belief in eventual relief but through their endurance of pain.

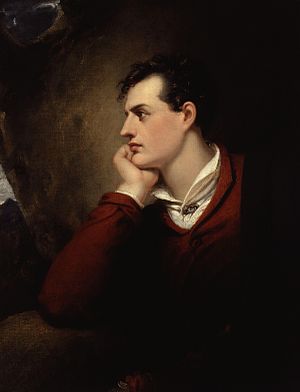

Suffering and despair are not necessarily pessimistic themes and emotions according to other critics, however. For example, an existential reading of some of Lord Byron's major works promotes the argument that one become's alert to one's own existence by experiencing despair.[12] The idea that awareness is achievable through despair and existential angst is supported by the theory that one learns best through experience, and that privilege and happiness unchecked, combined with a lack of education in topics of inequity and empathy, leads to ignorance and unproductive, false hope in humanity. For example, in celebrated Egyptian writer Naguib Mahfouz's short story "The Happy Man", the main character wakes up perfectly happy, a pleasant experience, only for him to realize with time that his happiness is interfering with his ability to care about important and pressing world issues as well as his work and social life.[13] Literature like this questions the role of happiness and suffering, and the morality of its experience in life and fiction, through a utilitarian lens. Additionally, themes of hope need not only arise from narratives that purposefully encode hopeful messaging. In literature, especially children's literature, the goal might possibly be not to inspire, but to depict the suffering of life as it truly is, and make it bearable. Books like Bridge to Terabithia by Katherine Paterson depict genuine trauma that is by all accounts meaningless and painful, but also creates hope in the sense that it teaches readers that sometimes life is unpredictable, it doesn't always have a happy ending, but it doesn't need to, and that's alright. Paterson wrote a children's story not about death, but about friendship, despite its inclusion of the suffering of loss.[14]

The role of suffering cannot fully be explored without also acknowledging its use and omission in escapist and cathartic literature. Although used interchangeably in colloquial discourse, in the context of literary hope theory, these two kinds of literature are not synonymous with each other. Escapist literature is connected to fantasy and to a psycho-emotional untethering from reality. While there are many forms of escapism in literature, it does tend to be seen as lesser-than in contrast to literature that aims to root itself in reality, analyze society, and expose the reason for despair within.[15] Cathartic literature is better defined as a means through which one can experience and face up to negative or typically unwanted emotions in a safe environment. For example, horror fiction is considered to be extremely cathartic, because it grants the reader a sort of psychological prophylaxis against fear. A reader can experience horror in fiction, and thus feel better prepared for horror in real life having already undergone an empirically harmless micro-dose of fear, anticipation, and anxiety. This form of literature has, in contrast to escapist literature, been seen as a respectable and serious one, or at least as an important component without which a literary work cannot be seen as respectable or serious.[16] For example, Carrie by Stephen King is horror novel now considered to be a classic for its themes regarding women, femininity, guilt, blame, sin, and sexuality.[17]

The connection to escape and catharsis may be one of the reasons suffering is such a divisive theme in literature. Since it has long been viewed as "deep" art by experts in the field, a counter-movement based in deconstructing literary elitism has arisen in retaliation, with the intention of defending the validity of contemporary art (as opposed to only praising classic art), respecting happy literature (as opposed to revering depressing literature), and bolstering art by marginalized groups (as opposed to only holding onto "old, dead, white men's" art). It is possible that in an effort to rectify the disparity between narratives of hope and anguish in literature, there has been an over-correction, resulting in a movement to disengage from themes of suffering and despair, or to at least to prevent the production of art revolving around these subjects. Alternatively, it is possible that most do not want the complete overhaul of depressing literature, but instead the increase in literary competency, the ability of readers to read politically and entertain multiple interpretations of a single text, both of hope and despair, instead of one or the other, radically implying the existence of hope and despair to be complementary rather than antagonistic in nature[18][19]

Realistic despair and true-to-life fiction[edit]

The trouble is that we have a bad habit, encouraged by pedants and sophisticates, of considering happiness as something rather stupid. Only pain is intellectual, only evil interesting. This is the treason of the artist: a refusal to admit the banality of evil and the terrible boredom of pain.

- "The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas", Ursula K. Le Guin

Suffering as a literary tool has sparked conversations around gratuitous violence, the necessity for the depiction of life-like misery, the self-indulgence of torture, and the reality of pain. Questions are inevitably raised: are hope and idealism signs of naivety, triviality, or bad faith, and is suffering (without hope) a sign of acquiescence, despair, or unproductive pessimism? Should fiction be depressing to be realistic? Should we entirely abandon realism and our "infatuation with fact, evidence, and the supposedly transparent realness of history or sociology"[20] in favor of embracing the transformative potential of hope?[21] Is disenchantment a sign of political awareness and sharp criticism? Is there room for wonder and imagination in the current climate of doubt in humanity, and in the world as a whole? Some critics will insist that hope is a complacent passivity, while others, such as political theorist and philosopher Professor Jane Bennett, believe that hope is a constructive, political activity.[22]

One of the best examples of this ostensible dichotomy between hope and suffering in literature is the reception of the acclaimed 2015 novel A Little Life by Hanya Yanagihara.[23] On one hand it was praised for being a realistic, unflinching, insightful exploration of human suffering in reviews such as "The Subversive Brilliance of A Little Life" by Jon Michaud in The New Yorker.[24] On the other hand, a now well-known and influential review by Daniel Mendelsohn in The New York Review inspired a new analysis of the narrative, one that is more critical of the execution of Yanagihara's dramatic tragedy. In his own words, Mendelsohn states that "in a culture where victimhood has become a claim to status, how could Yanagihara's book— with its unending parade of aesthetically gratuitous scenes of punitive and humiliating violence— not provide a kind of comfort? To such readers, the ugliness of this author's subject must bring a kind of pleasure, confirming their preexisting view of the world as a site of victimization and little else". The novel therefore holds an extremely divisive reputation, with some readings of the text yielding a cold, profitable, novelized take on torture porn,[25] while others maintain a nuanced, subversive take on personal trauma, explicitly rejecting "the identity politics that can be the source of the sort of victimization Mendelsohn outlines".[26] Other examples of possibly gratuitous or honest violence and suffering in literature include the A Song of Ice and Fire epic fantasy series by George R. R. Martin and its small screen adaptation Game of Thrones,[27][28] or the short story "A Coin" by Aleksander Hemon.[29]

Archaeologists study artifacts because they provide incite into the lives of the people in civilizations past. They are clues to how people lived and worked, as well as how they thought and what they valued. We live in a new age, and one day our own works, material and intellectual, may be studied, because, in a sense, the art and science we produce are reflections of the challenges, questions, and thoughts we are considering as a collective humanity in any given era.[30] It has been noted by Kristen Downey Randle that the social order, perhaps due to hopelessness, cynicism, post-structural nihilism, or increased immorality, no longer champions stories of choice, determination, perseverance, and triumph, instead tending to revere and respect "damaging" stories of mental illness, senseless pain, hypocrisy of family, and the inverse relationship between personal and communal salvation.[1]

For those convinced with the idea of fiction as an imitation or reflection of life, and considering the tendency of contemporary intellectual circles to value narratives of suffering and despair over happiness and hope, the question is: does there exist in our collective unconsciousness a core belief in doom? If so, this could be the result of an increased global awareness regarding topics of persisting racial and other social injustice, climate change, late-stage capitalism and political corruption. In his article "We Hope", playwright Max Frisch exposes the political powers at play in interrupting the possibility of peace, including governments' need for international "enemies" as an excuse to create military authority, which can then be used to subjugate their own peoples and maintain national power. Frisch also states as a matter of fact that the prognosis for humanity is, given political, environmental, economic and technological instability, dire. These are future projections, which may not prove true, the future is unforeseeable, but the certainty remains that this negative outlook on the world and the human race is both supported by certain facts and widely believed, creating a cultural narrative of doom which embraces an acceptance of the reality, often without the belief in or the urge to attempt to change the prognosis. This comfort with inaction and acceptance of the impossibility of a utopia is the mindset Frisch, as well as many other writers and activists, advocates against, urging readers to hope and believe in the possibility of peace, a revolutionary belief.[31] Ultimately, literature, and its interpretation, attempts to grapple with the need to appear true-to-life, which is often done through the portrayal of despair, since it is perceived as realistic, but also to inspire change, and disallow readers a validation in inactivity. Whether or not a core belief of doom exists in our collective unconsciousness is disputable, but it appears that regardless, we are not convinced with hope as a reality, but rather as a sort of naive, wishful thinking.[19]

Utopic vs. dystopic futures[edit]

Science fiction, speculative fiction, dystopian fiction, and utopian fiction are all genres of literature that deal with the future, and how society, thinking, and technology will have progressed. These genres can contain any amount of hope or despair the author sees fit, but unarguably, some forms of these narratives contain more hope than others. For example, young adult dystopian fiction has significantly altered adult dystopian fiction to include hope with novels such as A Wrinkle in Time by Madeleine L'Engle and The Giver by Lois Lowry which end on uplifting notes, as opposed to novels such as George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four (1984) or Kazuo Ishiguro's Never Let Me Go, which end on despairing or melancholy notes.[19] Speculative fiction, such as The Handmaid's Tale by Margaret Atwood, also tends to leave readers with an aftertaste of despair, because as Atwood, explains, speculative fiction is based in real laws, events, technology, and historical precedent. Everything related to society, politics, and science in a speculative fiction novel could viably occur, which makes dystopian worlds such as the Republic of Gilead so much more depressing and frightening[32][33] The function of such speculative and dystopic fictions seems to be primarily, but not solely, to act as deterrent from practices and frameworks that, if continued, may lead down a dark path. Atwood describes it as a sort of "antiprediction" of the future, in the sense that if it can be described, it may be prevented, though she acknowledges that such thinking is more wishful than productive acting on its own, and cannot be entirely depended upon.[34] Regardless, this provides pessimistic perceptions on life an important role to play in literature, and a potent defense of literary suffering. If all narratives provide hope, the idea spreads that everything is survivable and all pain is meaningful or necessary, which allows for terrible atrocities to occur, both passively (banal evil) and actively (radical evil), under the assumption that people as individuals and collectives will be able to handle any mistreatment and torture they are subjected to, thus making it alright or even desirable to subject them to it. Suffering and despair promote the idea that some horrors are too great to ever be allowed to occur, they are a warning and an inspiration to do better, to make sure the horrors of the present do not continue on into the future, or grow into worse versions of themselves.

This is not to imply that utopia does not have an important role to play in narratives and ideologies. In many ways, utopia is just as much a critique of the present as dystopia is, serving as a function of its presenting a more desirable future.[35] In utopian studies, the consideration of how to improve life after facing dissatisfaction with an aspect of it is called the Utopian Impulse. The "dreaming" of a better life, social dreaming, is what is defined as utopianism by Lyman Tower Sargent, "the dreams and nightmares that concern the ways in which groups of people arrange their lives and which usually envision a radically different society than the one in which the dreamers live".[36] Consequently, the concept of a utopia is the manifestation of hope as both an acknowledgement of reality and a challenge of current social conditions, as it not only criticizes the status quo, but also, in its correct form, offers constructive alternatives.[37] It is the means through which we obtain value in failure, the magnet of the compass which guides our lives, and the instrument of our transcendence,[31] since it creates a tension of human reality that constantly tends towards radical social transformation. This ideological framework which puts utopia in high regard is, however, criticized by philosophers and political theorists who orient their thinking more towards praxis, the practical applications of ideological rhetoric. These critiques apply not only to literature, but also to architecture, politics, and a variety of other fields. The tension between practice and project is outlined in a 1998 lecture given at Columbia university by architect and theorist Stan Allen.[38]

In the context of literary hope, it is difficult, impossible even, to arrive at an empirical answer, but topics of relevance and contention regarding utopic and dystopic visions of the future include: the possibility of these futures, inspected in literature such as the short story "Cat Pictures Please" by Naomi Kritzer, the cost of a utopia, explored in works such as "The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas" by Ursula K. Le Guin, and the desirability of utopia, questioned in narratives such as "The Happy Man" by Naguib Mahfouz. Literary critics and philosophers ponder on what to do with the possibility that a utopia cannot exist, that we may only be able to improve the world, and not fix it, and that though things may get better, they may never be good enough. It is also a matter of debate whether this thought of perseverance against all odds is one of pride, a testament to the strength of the human spirit, or one of despair, a Sisyphean torture.

A point of interest regarding speculative and science fiction and its relationship to hope is the interdisciplinary connection between literary hope theory and adaptation studies. As Dr. Alexander Charles Oliver Hall notes in his doctoral dissertation, fidelity criticism in the field of book-to-film adaptation has been losing relevance in recent years, replaced by an emphasis on post-structural, intertextual criticism, with a focus on analyses of films' interpretations of the original texts and the social and thematic implications of those reading. The ability to adapt texts into films has allowed adapters to "emphasize what they see as the utopian dimensions of source texts for potentially critical purposes, which equals a utopian function of adaptation in and of itself".[39] Utopia is therefore used as a method of interpreting the source text, the film adaptation, and the difference in thematic resonance between the two, creating room for more nuance than the usual "the book was better" claim. In "From Book to Film: Simplification" by Lester Asheim, a study of twenty-four novels adapted into film by American studios from 1935 to 1945, it is concluded that although unhappy endings are sometimes retained in book-to-film adaptations, like the death of the hero, negative endings, as distinct from affirmative endings, never are. Audiences tend to prefer affirmative resolutions in the sense that the morals of the heroes, and the rightness of the film's ideals are brought to fruition through the achievements of its hopes. It is a form of wish-fulfillment[40] which, according to Asheim, leads to the happiness or unhappiness of the ending not mattering, the important factor being that "nothing be retained in the film which will disturb the audience, and challenge it to think. An unhappy ending may be retained so long as it does not call into question the certainties and assurances with which the audience sustains it".[41] This may not apply to all films, especially in contemporary, post-structural contexts, but the idea remains that it is possible people are unsatisfied with or afraid of hopeless, uncertain endings, leading film-makers and producers to alter novel endings often, choosing a particular interpretation of the denouement rather than leaving it unresolved, a challenge to the audience.

Awareness, apathy, and their roles in activism[edit]

One popular pessimistic social view of hope is that of awareness and activism not being enough.[42] The concept of slacktivism has come to the forefront of social media circles,[43] especially in post-coronavirus America, since the pandemic and resultant quarantining led to an increase in interest in the news and therefore in social justice, as seen by the reinforced support for the Black Lives Matter movement in 2020[44] and other social justice movements such as Stop Asian Hate, ethical consumption advocating (i.e. fast-fashion alternatives, veganism, environmentally-conscious purchasing), Free Palestine, and ACAB. Slacktivism is the idea that people can implement activism through low-effort means, typically in a performative manner, in order to maintain social character through virtue signalling. It allows people to feel as though they've performed their moral duties and social obligations without the necessary investment, commitment, or involvement required of social reformists, revolutionaries, or physical (e.g. in-person protests) and intellectual (e.g publishing papers, manifestos, political calls to action) activists. In general, the effectiveness of slacktivism, and its net positive/negative impact are still irresolute.[45][46][47]

Because of the increased interest in engaging correctly in activism, doing the necessary work, and avoiding social faux-pas, there has been a lot of recent discussion on how to be better allies to marginalized groups, how to advocate for causes well, how to self-educate and raise awareness, and, in sum, how not to be a slacktivist. There is much debate on the topic of how much work is considered enough work to be considered well-educated, a good ally, or generally "woke". In the context of literary hope, there has been a movement to read books by black authors, by LGBTQIA+ authors, and by other author's of marginalized groups, for the purposes of self-education, inclusivity, and letting the subaltern speak (better known as 'hearing black/LGBTQIA+/etc. voices'). In response to that, and specifically in reference to literature, both fiction and non-fiction, skepticism has been raised on the meta-textual level about how helpful it is to simply read and educate ourselves about the problems suffered by people in modern societies worldwide. In a video published on the YouTube Channel "Hey it's Shey" titled "BOOKS CAN'T SAVE US | Diverse Reading, Community, and Booktube", the BookTuber, Shey, discusses the benefits and limitations of reading diversely, specifically in relation to performative activism, awareness, and anti-racism.[48] As a response to these sorts of anxieties surrounding good allyship and activism, books such as Pleasure Activism: The Politics of Feeling Good by Adrienne Maree Brown focus more on changing the perception of activism as a chore, and how it may be possible to include it within our lives so that it benefits both others and ourselves, and so we don't have to resort to slacktivism or apolitical, unproductive behaviors and thought patterns.

Within literature, short stories such as Lu Xun's "A Small Incident" still ring true in many respects,[49] though its themes regarding awareness, apathy, and activism are questionable. The narrative, published in July 1920,[50] takes place in 1917, and follows the apathetic main character (gender unspecified) who, trying to get to work on a windy, winter day, hires a rickshaw ride. On their way, the rickshaw collides with an old woman who falls to the ground and claims to be hurt. The narrator does not believe her at first, asking the rickshaw man to leave her and keep moving, but the man does not listen, instead helping the woman make her way to the police station to deal with the damage. The narrator has a psychological time-and-space altering metaphysical experience, resulting in a sense of exhaustion and newfound self-reflection, having been shaken out of their sense of detachment and apathy. They question their own intentions and character, but are left with no answers. Years later, they still recall the epiphany, which causes them distress and intra-personal reflection. The story considers themes of awareness and activism particularly in its final line: "Yet this incident keeps coming back to me, often more vivid than in actual life, teaching me shame, urging me to reform, and giving me fresh courage and hope".[50] The experience inspires awareness regarding issues of social inequality and ethics, and the narrator seems to find the memory of the incident inspirational and hopeful. In a sense, this is understandable because the thought that they are now more aware brings hope of change, but, on the other hand, this courage is in many respects unearned. The acquired awareness gives the narrator a sense of accomplishment, and it is enough for them to simply think of the incident and remember the lesson learned for them to feel better about their actions and self. But if a lesson learned is not sufficient cause for hope and courage, what is? In a sense, nothing we do can ever be enough. We all make an individual impact on the world, but that impact is so microscopic, it can even be argued to be null. Knowing that one can only control oneself is both a comfort and a prison, because though we may know how to fix the world, the healing is a collective effort, and convincing others to help is a near herculean task, often fruitless; ergo, a promoter of despair.[51][52]

Nihilism, in the literary and philosophical sense of the word, has been deployed as a response to disillusionment and despair, especially in the genres of modern satire, sparking worries that a nihilistic mindset can lull groups into disengaged apathy. Writers such as Wilfred Owen, Amiri Baraka, and Robert Penn Warren, however, dealt with the loneliness, beauty, and rage of these nihilistic ideologies, demonstrating that the life of meaninglessness is a threatening of existence, but also a framework we can live and effect change by, especially considering these poets and their works are now considered influential classics.[10] "A Small Incident" sparks conversation over whether awareness is enough, hope is earned, despair is valid, and knowledge is useful. How much are we ethically required to learn and do for us to be beneficial to social and environmental causes? What must literature do to properly depict and respond to these dilemmas? What attitudes are best fit for both a productive mindset, and a balanced, realistic-but-not-depressing, hopeful-but-not-delusional, perception of the world? The only consensus in this field seems to be that representation in literature is important,[53] that activism is a good way to be proactive rather than reactive, and that constantly practicing thoughtfulness, being gracious about admitting mistakes, and taking pains to correct them, is a good way to be an open-minded, helpful, rather than hurtful, person.[54][55]

Defeat[edit]

Status quo[edit]

The status quo, literally meaning "existing state" in Latin, is the current state of affairs, especially as it relates to political, socio-economic, and even religious issues.[56] Typically, the status quo is very difficult to change, maintained, against the efforts of revolutionary forces, through social norms, ethics, laws, governments, societies, traditions, punitive measures and even logical fallacies, all of which combine to form what is known as the status quo bias, an inertia blocking social change and reformation.[57] The status quo is often depicted in a negative light, especially by culturally left groups who value progress (progressives), on the basis that the current state of the world is not optimal for environmental, political, and social justice security[58]. Generally, the left is group-oriented, aiming to overhaul the status quo completely by doing away with old systems, such as prison reformation or police enforcement, and replacing them with new systems, because it perceives these establishments as being foundationally built on injustice and inequality (institutionalized misogyny, transphobia, racism, homophobia, etc.). For the left, it is not possible to change institutions built to oppress marginalized groups into institutions directed to protect them, it is imperative to create new systems built for the benefit of all. Culturally right groups who value tradition will typically attempt to maintain the status quo as it essentially epitomizes their values, specifically and especially status quo conservatives.[59] Right-wing politics are generally individualistic rather than collectivist. They often do not acknowledge institutional injustice, and focus more on personal struggle. When unfairness is recognized, it is usually within the context that nothing can be done to change these issues. Racism will always exist, so will misogyny, and prejudice of all kinds. There will always be such obstacles to success and happiness, and it is the individual's responsibility to work hard and triumph within the foundations of the system, not the system's responsibility to reform and support individuals. This is not to say the left supports a lack of individual agency, it simply believes in affording every person the same support system, because when structural inequalities and corruption pervade the foundations of social and economic enterprises, it is not considered both naive and unjust to expect every individual to be judged similarly based on their ability to find success.

Since literature often deals with and attempts to propagate political ideas, knowledge of authors' political leanings can help in deciphering how a narrative depicts, affects, and is affected by the status quo. This is useful in contextually informed literary criticism such as biographical criticism, as opposed to more objective approaches such as formalism. Political or cultural spectrums also influence the way specific plot arches, archetypes, and narrative devices are received. For example, the femme fatale character archetype is controversial because while the woman is seen as gaining dominance over men with her beauty and cunning, from a liberal perspective, she cannot achieve autonomy, because she still works within the constraints of patriarchy and is therefore dependent on it, and on men, to derive her strength from, instead of finding strength solely through her own humanity. Since the woman only achieves individual power, often at the cost of other women's rights, reputation, and efforts, not because of but despite her background, the femme fatale is an anti-feminist character, or at least a regressive view on female empowerment. However for the right, the femme fatale is a commendable success story, a dangerous wit, making use of all her assets in her search for power. The status quo affects not just individual narrative elements, but also overall themes in literature. Every narrative must, by virtue of its existence, interact with the status quo. Whether it affirms or denies, supports or questions it, depends on a range of factors.

Firstly, is the status quo positive or negative, and according to whom? Not all existing states must be harmful or irrational, some are utilitarian, or even arguably moral.[60] Additionally, some narratives will defend the status quo subversively (i.e showing a world in which the status quo continues unchanged, and all the pain suffered because of it, as a way to inspire change). The short story "The Lottery" by Shirley Jackson is an example of this subversive defense, as the story depicts a village set in its tradition of murdering a random villager every year, and the horror of its outcomes.[61]

Second, how does hope function within the status quo? It is a matter of perspective whether hope is an ingrained part of or challenge to a given society, an element dependent on the attitudes, values, and beliefs of the social order. In communities that tend toward "doomer" ideologies, like the one our society is reportedly reaching towards[62][63] and ones found in online spaces such as 4chan (where the term originated[64]), hope is a radical act of defiance. This is because the internet's doomerism is just another term for Sloterdijk's modern cynicism, which postulates that attempts at change, progress, and reformation are foredoomed, though we have to act as though they aren't. Modern cynicism is a disillusionment with society and politics so complete that the uselessness of preventative or rectifying action is understood.[65] Contrariwise, for communities that champion the "bloomer" mindset, that is, idealism, hope is inherently present. If the doomer philosophy is built upon the expectation of societal collapse, the bloomer philosophy is built on an optimistic projection of the future. Hence, idealist or bloomer communities will see hope as part of their function. The myth of Pandora's box is a great example of doomer and bloomer interpretations of narratives. The basic skeleton of the story as it is commonly known is that the Greek gods, upset with man, created the first human woman, Pandora, and sent her to marry someone. The gods then gifted the couple a container, sometimes a pithos, a box, or a jar, and told them not to open it. Pandora, however, because of the deceitful or curious nature bequeathed to her by the gods,[66] opened the box, thus unleashing sin and suffering into the world.[67] At the bottom of the box however, there remained hope, which fluttered out last.[68][69][70] A positive, hopeful, or bloomer reading of the text, and the most popular interpretation of it, suggests that despite all the pain and evil in the world, humans still have hope, and with it, strength.[71][72] A negative, despairing, or doomer reading of the text instead posits that the presence of hope in the box of sins and sorrows is not a gift but a further torture.[73] Hope is proposed as yet another instrument of pain; it prevents the human from reaching the acceptance of sin and sub-optimal circumstances. More importantly, it prevents people from reaching the relief of cynicism and the absolution from guilt for accepting the status quo. Without hope, the human condition would at least be understood and accepted, tolerable. With it, we are constantly tantalized with the thought of a better world which we could achieve if we could only do this, or change that, the same way Sisyphus feels that if he could only get his boulder one inch closer, it would finally be shoved onto a level plane and his task in Tartarus (hell) would finally be completed. The hope that if he only attempts it one more time, he will finally complete his task and be set free is what causes Sisyphus to engage in his own torture, when he could simply choose to stop.[74] Alternatively, hope may be seen as the water which Tantalus stands in, or the fruit that hangs overhead, a looming solution to the torture of starvation and thirst, within reach, but receding every time contact is initiated.[75]

The status quo is an aspect of literary hope that requires special attention, because the way in which it is reacted to in literature, whether through submission or heterodoxy, is a meaningful reflection on society's attitudes towards accepted standards and beliefs, as well as, of course, hope.

Fatalism, free will, and learned helplessness[edit]

Fatalism is a philosophy of the mind, conception of static and dynamic time theory, or faith in religious destiny which posits that every event that has or will ever happen, needed or needs to happen, as all of time is predestined to occur in a particular manner and sequence.[76] For example, a fatalist reading of Sophocles' Oedipus Rex results in an interpretation in which Oedipus kills his father and marries his mother, not because of the sequence of causal events that led to this conclusion, but because it was predestined to occur, no matter what had happened or who tried to stop it.[77]

The relation of fatalism to hope is that it is either a reaction to hopelessness, or a cause of it. Fatalism has been a sort of consolation to man throughout the centuries, including civilizations like Ancient Greece: as humans have realized the futility of their efforts, they have attempted to find cause for hope by interpreting events with the idea that all that has happened, is happening, and will happen is not within their control, they are relieved from the burden of that responsibility, since all experiences are inevitable and inescapable. Instead, events occur as preordained by the universe, God, karma or some force that binds the course of human existence to a set destiny, with a plan. In this interpretation of collective and personal histories, no pain is suffered in vain, every set-back, every thwarted hope is necessary, in service to this greater, beautiful destiny, which will make all endured suffering worthwhile.[78] Conversely, fatalism can be seen as a sort of prison in many respects, which robs individuals of their agency and power, leaving them mere puppets to greater forces. This more negative interpretation is distinguished from the first only in that it is received as an unwelcome truth, by minds that want the ability to effect change, rather than a generous relief.

Since fatalism is generally seen to deny free will to human beings, the reaction to it, regardless of whether it is happily or unhappily accepted, is similar to the behavioral attitude of defeatism and modern cynicism, which encourages acceptance and resignation, rather than resistance. This mental state and behavior can be a form of philosophical learned helplessness, since after an individual has been exposed to enough experiences in which they feel fate has controlled life more than they have (an aversive stimulus), they learn they are helpless to change or control their condition, and surrender power instead to other forces.[79] For this reason, there is often a disconnect in reason with pure fatalists, such as Nietzsche, who attack concepts of freedom or free will, but insist on the ability of humans to "make themselves". That is, to cultivate their talent, explore their identity, and distinguishing themselves as individuals.[80] The concept of resignation here is particularly of interest, because, as Sukumari Bhattachargi explains in "Fatalism - Its Roots and Effects", fatalistic attitudes, even more than defeatist ones, allow for extremely sinister events to occur which could easily have been preventable, such as the poor growth of crops, necessary for a farmer to sustain his livelihood being reacted to with: "This year the harvest was bound to fail, manure or no manure", when fertilizer could very well have helped, or the death of a child because of smallpox, to which the mother responds: "since the boy was 'fated' to die of smallpox no vaccination would have prevented his death", when smallpox is an eradicated disease, the vaccine of which could almost definitely have prevented his death (the reasoning behind a lack of vaccination here is not vaccine skepticism or anti-vaccination beliefs, it is more abstract).[81] The attitude of piety and resignation, not just in the face of greater systematic mechanisms over which no single person has complete control, but in the face of actionable issues, the results of which are directly contingent on the action or lack thereof of an agent, can thus be extremely harmful. The harm can be done both externally (i.e, physical, or to other people), internally (depression, anxiety, and other mental health problems), or a combination of the two, including social problems such as engaging in emotionally abusive relationships, child abuse, neglect, or alienation.[82][83] One reason "depressing" or fatalistic narratives may be controversial is for their ability to convince readers of their own helplessness, a dangerous power.

While fatalism used to be taken extremely seriously centuries ago, in recent years, it has been the subject of particular scorn and contempt, being regarded as foolish or absurd by many, such as Daniel Dennett, a philosopher, writer, and cognitive scientist who developed the "multiple drafts" theory of consciousness.[84] Nevertheless, fatalism has proved to have staying power as an effective literary device, which produces a sinister, fearful, and possibly magical effect in literature still.[85] A large part of the reason Shakespeare's play, Macbeth, is so highly celebrated is because of its themes of fate and free will. Was Macbeth fated to kill the king, or did the witches trick him? Was the prophesy a self-fulfilling one, or would it have been preventable, had it not been told to Macbeth? It is a classic archetypal narrative, the tragedy of a man coming up against a greater power, which defeats him, and the resulting fall from grace.[86] Paradise Lost by John Milton is concerned with a lot of the same questions and concerns regarding fate. Not all fatalistic texts reflect dark or dire, themes, though. The Alchemist by Paulo Coelho is a novel that deals in spirituality and mysticism, and which has a very clear message that every individual has a "personal legend", or destiny, that they must search for and work towards, and that this is essentially the meaning of life.[citation needed] In it, the main character a shepherd named Santiago, is confronted by a greater being whose job it is to propose tasks to humans in order to coax them towards their destiny. Santiago accepts and, after many set-backs and transcendent experiences, he finds his reward, buried treasure in the spot where he first began his quest, and true love along the way.[87] The moral of the story has resonated with many, as it is a sweet and succinct tale of the journey and the destination, the trouble life puts us through for the reward to feel as good as it does after an arduous and harrowing pilgrimage.[88] It is a novel of hope, not despite but because of its reliance on fate, and the idea that "when you want something, the whole universe conspires in order for you to achieve it".[89]

Complacency[edit]

Complacency is a subtle vice that has accrued many, often contradicting, definitions, including ideas of contentment, smugness, self-satisfaction, and ignorance towards issues of danger or inadequacy. The general concept of it is perhaps best defined by Professor Jason Kawall in the American Philosophical Quarterly article "On Complacency" as being "constituted by (i) an epistemically culpable overestimate of one's accomplishments or status that produces (ii) an excessive self-satisfaction that produces (iii) an insufficiently strong desire or felt need to maintain (or improve to) an appropriate level of accomplishment, that in turn produces (iv) a problematic lack of appropriate action or effort".[90] In the political sense of the word, complacency is often related to apolitical ideologies, with accelerationists and revolutionaries adopting a philosophy of anticentrisim that transcends even their own political beliefs, under the basis that radicalization and polarization will do more to shake the status quo than moderate views which can only reinforce it.[91][92][93] In the context of literary hope theory, complacency borrows these definitions, but also stresses passive complicity towards issues affecting the presence of hope in the future as its main concern, because hope is connected to the implementation of new ideologies.[94] Such issues include those of climate change and social justice, since their progression today, and the projections of how they will change, affect our collective perception of the future. Therefore, complacency in terms of literary hope theory, is an act of upholding current environmental, social, economic, and political issues as expressed through the lack of an attempt to take action against them.[95]

In an earlier section, the role of apathy in activism and complacency was discussed, but apathy is not the only antecedent to complacency. Ignorance, which usually comes from a place of privilege or internalized marginalization, can be one factor in promoting complacency.[90] If a person is not aware there is a problem, they cannot knowingly do anything to help solve it. One psychological component in creating inaction is dread. When a substantial, negative prospect is brought to attention, a person might feel intimidated by the sheer complexity of the issue. It then follows that the problem grows in the mind of that person, leading to a psychological paralysis.[96] This phenomenon is also related to procrastination and why it is so difficult to overcome, as opposed to the common belief that it stems solely and invariably from a place of laziness.[97] The fear of failure, or that the person will not be up to the task, is a problem related to low self-esteem, social problems, depression, and anxiety.[98] It can also be that the person has learned so much about an issue that they now understand the mechanisms keeping it from being solved, and feel overwhelmed and powerless to effect change, modern cynicism or defeatism. There is plenty of reason for anger and despair, and some people become so consumed with their dissatisfaction with the present state of the world that it does not occur to them to engage in creating solutions to those problems, or indeed that solutions are even possible.[96] Yet another reason for complacency is that taking action is difficult and requires mindfulness, time, and in some cases, sacrifice. A person might be convinced with arguments advocating for veganism, but not be willing to give up meat, fish, or milk.[99] A person might know that consuming fast fashion products is unethical because of the way certain brands exploit their workers and because of their effect on water pollution and waste production, but be unwilling to give up the access to relatively cheap and trendy clothes. A person might believe in climate change, and care about the environment, but not be willing to stop using plastic bottles and bags, or quit smoking. Furthermore, people may be willing and knowledgeable, but unable to take action. For example, in societies experiencing late-stage capitalism, with a shrinking middle class, many people are not able to afford environment-friendly, vegan alternatives to basic necessities such as food and clothes. Producing environmentally friendly clothes is expensive, which makes the clothes themselves pricier, and so fast-fashion becomes the only viable choice for affordability.[100] Other forms of sustainable living, such as sustainable homes, also have questionable affordability.[101] In underdeveloped and developing countries, such alternatives may not even be available.[102] Despite the difficulties of understanding and fighting for the resolution of global issues, many environmental, political, and cognitive scientists stress that the world is not yet beyond saving, and that we should not fall prey to the unproductive complacency of despair, but rather recognize the role of suffering in bringing about change, and do our part at least, trusting that others will do the same.[103]

An important distinction to make, especially as it relates to hope, is individual vs. group complacency. Beyond our individual responsibilities, there are still structures above us that may be complacent, too, such as large corporations, governments, and institutions, which arguably absolve individuals from personal responsibility.[104] If complacency is more individualistic, there may be hope for change through the popularization of certain beliefs and behaviors, whereas institutionalized complacency is much harder to change, considering corruption, bureaucracy, and other barriers to progress. For example, if one or a few police officers are corrupt and/or complacent in perpetuating unequal treatment of African Americans in America, they can be possibly worked with and educated. Alternatively, if this is not a viable option, they could simply be asked to leave the police force. But if the complacency is inherent within and promoted by the organization, a police officer may not be considered at fault for the institutionalized bigotry and inequality it shows towards people of color in the course of police brutality, which is the ideology behind the ACAB movement. It is not that every individual "cop" is corrupt, racist, or evil, but rather that the organization they work for is, making them vessels through which institutional complacency is played out[105].

From an ethical standpoint, moral complacency, not to be confused with moral relativity, is the implication that each culture has the right to determine its own obligations, that its social practices are self-justifying, and that its ethics are beyond questioning.[106] Moral complacency is similar to a host of logical fallacies which may aid in understanding the concept better, including appeal to tradition, bandwagon fallacy, argument from adverse consequences, appeal to improper or biast authority, non sequitur, red herring, slippery slope, false dichotomy, and loaded question fallacy. This is because moral complacency tends to attribute moral truth to individual cultures, under the misunderstanding that it is related to moral relativity. However, its sweeping rejection of criticism makes it liable to ignoring any form of corruption, injustice, or abuse of power, under the guise of respect for tradition, culture, and history. It implies that the ethical thing to do is to follow the dictations of the culture you belong to, because if you don't you will create discord and offend those who love and care about you. These logical fallacies are built to gaslight individual thinkers and coerce conformity, despite the fact that critiquing one's own culture can also be an act of love and care towards it, much the way parents and guardians critique children in order to see them do better. Even so, cultures that are inherently more conformist may spread the idea that self-critique is anti-patriotic and/or anti-nationalistic, a sign of internalized colonization (for post-colonial states). They may imply that criticism is equal to becoming a race-traitor, even, and propagate the mindset that there must be a choice made between loving your culture blindly or abandoning it entirely.[107][108] Moral complacency may be more controversial than other forms of complacency since it is more related to culture and tradition, and therefore to the left-right political divide.

Complacency in literature is almost as common as interactions with the status quo, since the two are intrinsically related. The short story "The Falling Girl" by Dino Buzzati follows the main character Marta as she drop from the top of a skyscraper to the ground, aging in years as she nears the bottom. This form of suicide is extremely common for this building, as people, mostly girls, go to it to jump off, and after Marta jumps, many other women soon join her. The tenants of the building, and everyone nearby who knows of this occurrence, are not concerned with why this happens or how to stop it. The landlord simply charges more for the rent of apartments near the top of the building because they provide a good view of the girls falling while they are still young and beautiful. The tenants in apartments near the bottom of the building can't afford the higher prices above, and so they settle with at least being able to hear the thud of the girls as they hit the floor.[109] The worldbuilding of "The Falling Girl" is, from a literary hope perspective, under the theory of complacency, an amplified, absurdist take on the complacency of people in contemporary society. Everyone in the story is so desensitized to this violence and suffering, it is at best good entertainment, and at worst, dissatisfying entertainment. No one is capable of seeing the women falling to their deaths as anything besides that. No one takes initiative to get to the bottom of the suicides, and no one feels a responsibility or a duty of care. In fact, since it is a part of their community's culture to delight in the fall of girls (an allegory for the suffering or even death of marginalized, outsider groups) it may even be taboo to question it, because of enforced moral complacency. In which case, some people may feel genuine concern for the girls, and may want to help them, such as the young man who reached out to Marta has she fell, but are too self-serving or scared to deal with the social consequences of that, selfish or paralyzed complacency. Regardless, there is an acute sense that the people who live in the skyscraper are both complacent and complicit in the deaths of the falling girls.

The human spirit[edit]

Endurance[edit]

To begin with, endurance refers to the ability to endure an unpleasant or difficult process or situation without giving away. When discussing the themes of hope and despair in literary works, it is important to mention how us human beings are considered strong and we can endure so much. Human beings have been through a lot of suffering and misery and have survived and are still fighting. This shows us how much us humans can tolerate and endure. Thus, we can find some kind of hope in every narrative since it shows us the endurance of the human spirit. When reading texts related to hope and despair, it is clearly portrayed how much humans go through every single day and all the things they have to tolerate. They come back stronger and it is clearly portrayed how their spirit can handle and endure a lot of things. This is how we know there is some kind of hope in the narrative. The unifying factor that brings us all together is the endurance of the human spirit and our perseverance.[110] Therefore, the endurance of the human spirit shows us that us humans can endure and tolerate so much. In addition, it is a significant topic to mention when talking about hope and despair.

Solidarity[edit]

In a large number of literary texts, we can relate to characters that are in pain and suffering. These characters in pain may be seen as symbols of solidarity with people who are actually suffering in real life. In a way or another, it is like giving those characters in pain a voice. This way, they will have hope that their voices can be heard and that they are not inferior. Those characters usually suffering from injustice and marginalization so giving them a voice will provide some kind of hope for them since they represent solidarity. Therefore, the characters suffering and people who are suffering in real life will form a unity.

Personal and societal growth[edit]

As us humans work on getting better and make our societies more developed, we plant some kind of hope in ourselves that there is always place for improvement and that we can always grow more. Progress and advancement is a process and we shall always work on ameliorating our individual selves in addition to our societies so we can live in a developing/developed world. Having hope that we can grow personally and on a global level is very important. If we do not have hope that we can achieve this goal, then we won't be able to get there. Thus, personal and societal growth are two important aspects when it comes to the human spirit when discussing the literary hope theory.

See also[edit]

- Defeatism

- Disappointment

- Optimism

- Optimism Bias

- Fatalism

- Free Will

- Pessimism

- Delusion

- Naivety

- Suffering

- Awareness

- Activism

- Slacktivism

- Status Quo

- Learned Helplessness

- Revolutionary Defeatism

- Incorrigibility

- Solidarity

- Capitalism

- Marxism

- Oppression

- Apocalypse

- Ecological Grief

- Accelerating Change

- Social Development

- Social Change

- Social Justice

- Social Order

- Social Regress

- Sociocultural evolution

- Technological progress

- Techno-Progressivism

- Happiness Economics

References[edit]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Randle, Kristen Downey (2001). "Young Adult Literature: Let It Be Hope". The English Journal. 90 (4): 125–130. doi:10.2307/821933. ISSN 0013-8274. JSTOR 821933.

- ↑ Griesinger, Emily (June 2002). "Harry Potter and the "Deeper Magic": Narrating Hope in Children's Literature". Christianity & Literature. 51 (3): 455–480. doi:10.1177/014833310205100308. ISSN 0148-3331.

- ↑ "MEX-M-MRS-1-2-3-NEV-0001". MEX-M-MRS-1-2-3-NEV-0001. doi:10.5270/esa-fg9m086. Retrieved 2022-04-25.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Tyson, Herb (2014-06-25), "The X Files: Understanding and Using Word's New File Format", Microsoft Word 2010 Bible, Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., pp. 91–99, doi:10.1002/9781118983966.ch5, ISBN 978-1-118-98396-6, retrieved 2022-04-25

- ↑ Park, Jonggyu; Eom, Young Ik (August 2019). "URS: User-Based Resource Scheduling for Multi-User Surface Computing Systems". IEEE Transactions on Consumer Electronics. 65 (3): 426–433. doi:10.1109/tce.2019.2924480. ISSN 0098-3063. Unknown parameter

|s2cid=ignored (help) - ↑ "Hope and naivety". swopaplot. 2007-01-14. Retrieved 2022-04-25.

- ↑ Snyder, C.R.; Rand, Kevin L.; King, Elisa A.; Feldman, David B.; Woodward, Julia T. (September 2002). ""False" hope". Journal of Clinical Psychology. 58 (9): 1003–1022. doi:10.1002/jclp.10096. ISSN 0021-9762. PMID 12209861.

- ↑ "Validate User". academic.oup.com. Retrieved 2022-04-25.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Freytag, Gustav; MacEwan, Elias J. (1900). Freytag's Technique of the drama : an exposition of dramatic composition and art. An authorized translation from the 6th German ed. by Elias J. MacEwan. Robarts - University of Toronto. Chicago : Scott, Foresman. Search this book on

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Jackson, Patrick Earl (2007). This side of despair : forms of hopelessness in modern poetry. UMI Dissertation Services. OCLC 807725182. Search this book on

- ↑ Bentley, Paul (2000). "'Hitler's Familiar Spirits': Negative Dialectics in Sylvia Plath's 'Daddy' and Ted Hughes's 'Hawk Roosting'". Critical Survey. 12 (3): 27–38. doi:10.3167/cs120303. ISSN 0011-1570. JSTOR 41557061.

- ↑ Pauly, Jason (2010). Designing Byron's Dasein : the anticipation of existentialist despair in Lord Byron's poetry. Library and Archives Canada = Bibliothèque et Archives Canada. ISBN 978-0-494-53683-4. OCLC 729988196. Search this book on

- ↑ al-Gabalawi, Saad (1977). Modern Egyptian short stories. York Press. OCLC 432649458. Search this book on

- ↑ Paterson, Katherine (1982). "The Aim of the Writer Who Writes for Children". Theory into Practice. 21 (4): 325–331. doi:10.1080/00405848209543026. ISSN 0040-5841. JSTOR 1476360.

- ↑ Heilman, Robert B. (1975). "Escape and Escapism Varieties of Literary Experience". The Sewanee Review. 83 (3): 439–458. ISSN 0037-3052. JSTOR 27542986.

- ↑ Golden, Leon (1962). "Catharsis". Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association. 93: 51–60. doi:10.2307/283751. JSTOR 283751.

- ↑ Beahm, George W. (1998). Stephen King from A to Z. Internet Archive. Andrews McMeel Pub. ISBN 978-0-8362-6914-7. Search this book on

- ↑ Kokkola, Lydia (2013-09-01). "Learning to read politically: narratives of hope and narratives of despair in Push by Sapphire". Cambridge Journal of Education. 43 (3): 391–405. doi:10.1080/0305764X.2013.792784. ISSN 0305-764X. Unknown parameter

|s2cid=ignored (help) - ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Reber, Lauren Lewis. Negotiating hope and honesty : a rhetorical criticism of young adult dystopian literature. OCLC 64392166. Search this book on

- ↑ Castiglia, Christopher (2017-09-26). Practices of Hope. NYU Press. doi:10.18574/nyu/9781479818273.001.0001. ISBN 978-1-4798-1827-3. Search this book on

- ↑ Blas Pedreal, Marlenee (2013-01-01). "Hope as a Potential Transformative Power". The Vermont Connection. 34 (1).

- ↑ Bennett, Jane (2001). The enchantment of modern life : attachments, crossings, and ethics. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-08812-8. OCLC 45618350. Search this book on

- ↑ "Debate erupts as Hanya Yanagihara's editor takes on critic over bad review of A Little Life". The Guardian. 2015-12-02. Retrieved 2022-04-17.

- ↑ "The Subversive Brilliance of "A Little Life"". The New Yorker. 2015-04-28. Retrieved 2022-04-16.

- ↑ Bloom, Ester (2015-11-19). "The Unprecedented Success Of, And Backlash To, A Little Life". The Billfold. Retrieved 2022-04-16.

- ↑ "Opinion | 'A Little Life,' 'Room,' 'Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt' and the culture of trauma". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2022-04-16.

- ↑ Conway, Jack (2010-01-01). "Unbowed and Unbroken". Radical History Review. 2010 (106): 163–171. doi:10.1215/01636545-2009-025. ISSN 0163-6545.

- ↑ Lystad, Reidar P.; Brown, Benjamin T. (2018). ""Death is certain, the time is not": mortality and survival in Game of Thrones". Injury Epidemiology. 5 (1): 44. doi:10.1186/s40621-018-0174-7. ISSN 2197-1714. PMC 6286904. PMID 30535868.

- ↑ Haske, Joseph Daniel (2016). "Honest Violence in Aleksandar Hemon's "A Coin"". Pleiades: Literature in Context. 36 (1): 165–167. doi:10.1353/plc.2016.0053. ISSN 2470-1971. Unknown parameter

|s2cid=ignored (help) - ↑ Hesseltine, William B. (1982). "The Challenge of the Artifact". The Wisconsin Magazine of History. 66 (2): 122–127. ISSN 0043-6534. JSTOR 4635715.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Frisch, Max; Riggan, William (1986). "We Hope". World Literature Today. 60 (4): 536–540. doi:10.2307/40142725. ISSN 0196-3570. JSTOR 40142725.

- ↑ "Margaret Atwood, the Prophet of Dystopia". The New Yorker. 2017-04-10. Retrieved 2022-04-18.

- ↑ "Margaret Atwood on Science Fiction, Dystopias, and Intestinal Parasites". Wired. 2013-09-21. ISSN 1059-1028. Retrieved 2022-04-18.

- ↑ Atwood, Margaret (2017-03-10). "Margaret Atwood on What 'The Handmaid's Tale' Means in the Age of Trump". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2022-04-18.

- ↑ Bloch, Ernst (1996). Utopian function of art and literature : selected essays. M.I.T. Press. ISBN 0-262-52139-3. OCLC 264683164. Search this book on

- ↑ Tower Sargent, Lyman (1994). "The Three Faces of Utopianism Revisited". Utopian Studies. 5 (1): 1–37. ISSN 1045-991X. JSTOR 20719246.

- ↑ Zournazi, Mary (2003). Hope : new philosophies for change. Lawrence and Wishart. ISBN 0-85315-955-6. OCLC 796072223. Search this book on

- ↑ Allen, Stan (1999). "Practice vs Project". PRAXIS: Journal of Writing + Building. 1: 112–125. ISSN 1526-2065. JSTOR 24328803.

- ↑ Hall, Alexander Charles Oliver. Reel hope : literature and the utopian function of adaptation. OCLC 863623582. Search this book on

- ↑ Bennett, James R.; Lindell, Richard L. (1979). "The Endings of Filmed Adaptations of Literature 1946-1977". Studies in Popular Culture. 2 (1): 59–76. ISSN 0888-5753. JSTOR 23412998.

- ↑ Asheim, Lester (1951-04-01). "From Book to Film: Simplification". Hollywood Quarterly. 5 (3): 289–304. doi:10.2307/1209664. ISSN 1549-0076. JSTOR 1209664.

- ↑ Gregory, Anthony (2020). "2020: The American Revolution that Wasn't". Istituto Affari Internazionali (IAI).

- ↑ Waugh, B; Hashemi, O; Rahman, SA; Abdipanah, M; Cook, DM (2014). "Twitter Deception and Influence: Issues of Identity, Slacktivism, and Puppetry". Journal of Information Warfare. 13 (1): 58–71. ISSN 1445-3312. JSTOR 26487011.

- ↑ Quarcoo, Ashley; Husaković, Medina. "Racial Reckoning in the United States: Expanding and Innovating on the Global Transitional Justice Experience". Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Retrieved 2022-04-18.

- ↑ Kristofferson, Kirk; White, Katherine; Peloza, John (2014-04-01). "The Nature of Slacktivism: How the Social Observability of an Initial Act of Token Support Affects Subsequent Prosocial Action". Journal of Consumer Research. 40 (6): 1149–1166. doi:10.1086/674137. ISSN 0093-5301.

- ↑ Chiweshe, Manase Kudzai (2017). "Social Networks as Anti-revolutionary Forces: Facebook and Political Apathy among Youth in Urban Harare, Zimbabwe". Africa Development / Afrique et Développement. 42 (2): 129–147. ISSN 0850-3907. JSTOR 90018194.

- ↑ Zeitzoff, Thomas (2017). "How Social Media Is Changing Conflict". The Journal of Conflict Resolution. 61 (9): 1970–1991. doi:10.1177/0022002717721392. ISSN 0022-0027. JSTOR 26363973. Unknown parameter

|s2cid=ignored (help) - ↑ BOOKS CAN'T SAVE US | Diverse Reading, Community, and Booktube, retrieved 2022-04-18

- ↑ Ramzy, Austin (2011-10-20). ""A Small Incident": Echoes of China's Tragic Yue Yue Case from Almost a Century Ago". Time. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved 2022-04-18.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 "An Incident". www.marxists.org. Retrieved 2022-04-18.

- ↑ Hannan, Michael T.; Freeman, John (1984). "Structural Inertia and Organizational Change". American Sociological Review. 49 (2): 149. doi:10.2307/2095567. JSTOR 2095567.

- ↑ Elder, Glen H. (1994). "Time, Human Agency, and Social Change: Perspectives on the Life Course". Social Psychology Quarterly. 57 (1): 4–15. doi:10.2307/2786971. ISSN 0190-2725. JSTOR 2786971.

- ↑ Banducci, Susan A.; Donovan, Todd; Karp, Jeffrey A. (2004). "Minority Representation, Empowerment, and Participation". The Journal of Politics. 66 (2): 534–556. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2508.2004.00163.x. ISSN 0022-3816. Unknown parameter

|s2cid=ignored (help) - ↑ Perez, Craig Santos (2019). "Guam and Literary Activism". World Literature Today. 93 (4): 68–70. doi:10.7588/worllitetoda.93.4.0068. ISSN 0196-3570. JSTOR 10.7588/worllitetoda.93.4.0068. Unknown parameter

|s2cid=ignored (help) - ↑ Gray, Herman (2016). "Precarious Diversity". In Curtin, Michael; Sanson, Kevin. Precarious Diversity: Representation and Demography. Precarious Creativity. Global Media, Local Labor. University of California Press. pp. 241–253. JSTOR 10.1525/j.ctt1ffjn40.22. Retrieved 2022-04-18. Search this book on

- ↑ "Definition of STATUS QUO". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 2022-04-19.

- ↑ Samuelson, William; Zeckhauser, Richard (1988). "Status Quo Bias in Decision Making". Journal of Risk and Uncertainty. 1 (1): 7–59. doi:10.1007/BF00055564. ISSN 0895-5646. JSTOR 41760530. Unknown parameter

|s2cid=ignored (help) - ↑ Uraizee, Joya F. (2006). "Subverting the Status Quo in Sénégal: Djibril Diôp Mambety's "Hyenas" and the Politics of Liberation". Literature/Film Quarterly. 34 (4): 313–322. ISSN 0090-4260. JSTOR 43797307.

- ↑ Stenner, Karen (2009). "Three Kinds of "Conservatism"". Psychological Inquiry. 20 (2/3): 142–159. doi:10.1080/10478400903028615. ISSN 1047-840X. JSTOR 40646411. Unknown parameter

|s2cid=ignored (help) - ↑ Nebel, Jacob M. (2015-01-01). "Status Quo Bias, Rationality, and Conservatism about Value". Ethics. 125 (2): 449–476. doi:10.1086/678482. ISSN 0014-1704. Unknown parameter

|s2cid=ignored (help) - ↑ ""The Lottery," by Shirley Jackson". The New Yorker. 1948-06-19. Retrieved 2022-04-19.

- ↑ Franzen, Jonathan (3 February 2021). What if we stopped pretending?. ISBN 978-0-00-846965-8. OCLC 1237198136. Search this book on

- ↑ Knibbs, Kate. "The Hottest New Literary Genre Is 'Doomer Lit'". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Retrieved 2022-04-19.

- ↑ Tiffany, Kaitlyn (2020-02-03). "The Misogynistic Joke That Became a Goth-Meme Fairy Tale". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2022-04-19.

- ↑ "• Peter Sloterdijk, A Critique of Cynical Reason, trans. Michael Eldred (London: Verso, 1988), 598 pp., £19.95 (paperback)", Textual Practice, Routledge, pp. 144–156, 2005-10-26, doi:10.4324/9780203990384-10, ISBN 978-0-203-99038-4, retrieved 2022-04-19

- ↑ Wolkow, B. M. (2007). "The Mind of a Bitch: Pandora's Motive and Intent in the Erga". Hermes. 135 (3): 247–262. ISSN 0018-0777. JSTOR 40379125.

- ↑ Glenn, Justin (1977). "Pandora and Eve: Sex as the Root of All Evil". The Classical World. 71 (3): 179–185. ISSN 0009-8418. JSTOR 4348824.

- ↑ Harrison, Jane E. (1900). "Pandora's Box". The Journal of Hellenic Studies. 20: 99–114. doi:10.2307/623745. ISSN 0075-4269. JSTOR 623745. Unknown parameter

|s2cid=ignored (help) - ↑ The Poems of Hesiod. University of California Press. 2017-08-01. doi:10.1525/9780520966222. ISBN 978-0-520-96622-2. Search this book on

- ↑ Hesiod (1989). Theogony. ISBN 0-19-251038-X. OCLC 1079433785. Search this book on

- ↑ Calder, William M.; Hesiod; West, M. L. (1967). "Hesiod, Theogony. With Prolegomena and Commentary". The Classical World. 60 (9): 376. doi:10.2307/4346286. ISSN 0009-8418. JSTOR 4346286.