Social construction of schizophrenia

Social constructionism, a branch of sociology, queries commonly held views on the nature of reality, touching on themes of normality and abnormality within the context of power and oppression in societal structures.

The concept of a social construction of schizophrenia, within a social construction of health and illness notary form, denotes that the label of schizophrenia is one that has been socially constructed through ideological systems, none of which are truly empirical especially as currently there is no definitive evidence as to the aetiology of schizophrenia.

Introduction[edit]

In 1966, Berger and Luckman coined the term social constructionism in their work The Social Construction of Reality. In summary it examines the basis of fact and truth / knowledge within culture. While some truths such as "fire is hot" are universally agreed as objective, many others considered 'fact' are the result of a common subjective experience and the subsequent validation of that.

Walker has argued that psychiatric diagnoses are nothing but linguistic abstractions. He has criticized the DSM-IV's poor reliability and postulated that terms like schizophrenia and mental illness only exist by consensus and persist by convention. Further he argues that the pathologizing language which persists in the medical model of disability is unhelpful in working towards a recovery model.[1]

Other notable practitioners and authors within the humanistic tradition that have viewed schizophrenia as a social construction include psychiatrist Thomas Szasz, Joseph Berke, R.D. Laing, Erich Fromm and Mary Barnes. Szasz viewed the diagnoses as a fabrication that is borderline abusive in terms of treatment. Szasz has protested against the taxonomic classifications of mental illness and reification of these as science, and has long argued against institutionalisation as a fundamental deprivation of liberty. In Berke's and Barnes's book two accounts of a journey through madness, Berke explores themes of psychosis as an enriching experience. Berke argues that the invalidation of schizophrenic experiences labelled 'sick or mad' is a uniquely western standpoint insofar as dream states and altered perception are not considered valid modes of interpolation of the truth within westernised culture.[2]

Laing (1964) commented "the mad things done and said by the schizophrenic will remain essentially a closed book if one does not understand their existential context".[3]

Noll (1983) has explored the links between shamanism and schizophrenia, testing the research evidence on shamanism against the DSM-III diagnostic criterion. Though he draws comparisons between the two states of mind in terms of the phenomenon experienced, he draws out important differences between shamanic and schizophrenic states, notably that many people on the schizophrenic spectrum do not voluntarily enter an altered state of consciousness whereas research into shamanism unilaterally shows that shamanic states are induced and controlled voluntarily by the shaman, who ultimately maintains a healthy world view between a base line level of consciousness and an altered state of consciousness. He concludes that differences between schizophrenic and shamanic states such as 'volition', mean that the DSM-III cannot be used to define shamanism as the same state as schizophrenia.[4] Robert Sapolsky has theorized that shamanism is practiced by schizotypal individuals rather than those with schizophrenia.[5][6][7]

Themes[edit]

Philosophy[edit]

Themes in social constructionism draw on various philosophies centred around the differences between objective reality or that which is known or absolute and subjective reality or that which is observed by the knower. In Schizophrenia: A scientific delusion, Mary Boyle explores 'schizophrenia and its assumptions as truths or knowledges which are socially produced and managed'.[8]

Linguistics[edit]

Michael Walker examines the social construction of mental illness and its implications for the recovery model. He is critical of the user becoming defined by the definer, such as if you go for behavioural therapy you come out with a perspective of rewards and punishments, etc.:

Psychology, like psychiatry, has found ways of linguistically contorting, convoluting, and confusing lived experience with essential "truths" of its own. Bill O'Hanlon, a preeminent postmodern consultant and author, uses his holiday cookie making experience to communicate what happens in the therapy room (O'Hanlon and Wiener-Davis, 1989). A client's problem that s/he brings to therapy is like cookie dough. The experience of it is vague and malleable. Once the "blob" of cookie dough is forced through the cookie press (a tube, funnel, and mold pressed against a baking pan) it becomes a Christmas tree, star, or Santa Claus. Similarly, when a client exposes his or her problem to a therapist it gets "molded" or interpreted in the language of the therapist. So a client attending a psychodynamic therapy session would leave having unresolved childhood conflicts. The same client leaving a behaviorist's office would walk away with problem behavior shaped by reward and punishment. An interaction with a Jungian therapist would result in the need to deal with the various archetypes that apply to him or her. Talking with a diagnostically (and thereby pathologically) minded clinician will leave one with the idea that they "have" "bipolar disorder", "depression", "obsessive compulsive disorder", a "mental illness" – along with all the stories that go with them ("chemical imbalances", lifelong duration, the need to "comply" with a treatment regimen, etc.). Like cookies, continued exposure to the "heat" of the theoretical lens causes these interpretations to "harden" or "reify" (to make real)." O'Hanlon concludes that if our languaging creates "the problem" then why not leverage the use of language and create a problem that is easiest to solve.[9]

He is critical of a deficit-based vocabulary:

From the perspective of linguistics we see that the reified categories (e.g. mental illness, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder) are abstractions defined by clusters of what we call "symptoms". Schizophrenia is defined as the presence of audio hallucinations (or other "thought disorders") in the absence of a "mood disorder". You can even throw in other correlates like "negative symptoms", PET scans, response to medications, etc. The issue of the DSM's poor reliability and validity aside (Caplan, 1995; Sparks, Duncan, & Miller, 2005), the term "schizophrenia" is a word used to communicate the presence of these "symptoms". The various human manifestations of thought, feeling, and behavior (aka "symptoms") exist like the chair you are sitting on as you read this exists. But the next level of abstraction, the word "schizophrenia", and the next, "mental illness", only exist through consensus and only persist by convention. Even if the correlations of defining symptoms was perfect (which it is far from), in light of the linguistic paradigm we have to ask ourselves whether using a pathologizing, deficit-based vocabulary is useful in helping people improve the quality of their lives.[9]

Power and control[edit]

Post Structuralist Jürgen Habermas examines questions of identity in the concept of societal integration and discusses how change occurs when there is a legitimation crisis. It assists the understanding of the social construction of schizophrenia and other illness in also understanding forces that shape power imbalances in aetiologies. Phil Brown in Naming and Framing: The social construction of diagnosis and illness points out how professionals were very slow and unwilling to accept the diagnosis of tardive dyskinesia, despite many research indicated warnings on it, as it was caused by prescription drugs that had been plaudited to be successful in treatment of the associated condition of psychoses. Market forces in pharmacology and/or cultural embarrassment can shape the rate at which society adapts to include new frameworks such as those demonstrated in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. [10]

Conrad writes on medicalization and social control. He looks at the process of science and medicalization. Science is heralded as the new religion in terms of ideological power and Conrad describes how medicalization can be used to police morals.[11]

In "The social construction of illness, key insights and policy implications", Conrad and Barker trace the history of the construction of illness from symbolic interactionists and medical sociologists and examine how society reacts in situations to the distinctions such as the construction of gender from sex and the construction of illness from disease:

Framing anger in women as evidence of the disease PMS, to be treated with antidepressants, trivializes the impact of gender inequality on women's daily lives. And when difficulties in children's attention and behavior get defined as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), school policies increasingly encourage the use of medication and special accommodations for learning disabled students; yet these responses fail to address the social and nonmedical causes of children's classroom inattention or agitation, such as increasing class size or the termination of physical education programs (Conrad 1975).

In each case, and many others, the process by which human problems become medicalized in the first place is largely ignored in creating policy toward these issues. A social constructionist approach provides a means of understanding how such problems come to be defined in medical terms and how this translates into public policy (see Gusfield 1981). As the above examples attest, medicalized constructions can also be strongly evaluative (i.e., they suggest how people ought to behave) and result in policies that authorize social control.[12]

They conclude that in an information age, new social groupings emerging may challenge the social constructions of illness and force policy changes.

Foucault examines power systems that incur on the operation of institutions and professionals:

The first task of the doctor is ... political: the struggle against disease must begin with a war against bad government." Man will be totally and definitively cured only if he is first liberated...[13]

The UK Parliament, in a key issues statement for 2015, references a 1957 statement by the Royal Commission, but queries its impact some 60 years later:

Most people are coming to regard mental illness and disability in much the same way as physical illness and disability[14]

Anti-stigma campaigns and the growing profile of mental health issues in recent years appear to have gone some way to changing views and dispelling misconceptions about mental illness. But with nine in ten people with mental health problems still experiencing stigma and discrimination, nearly sixty years after the Royal Commission's optimistic assessment, there may still be some way to go in changing public attitudes.[15]

The self and identity[edit]

Research directions here are on the importance of experiential narrative within psychiatric dialogue. Some research is critical of modern psychiatric adoption of an 'empiricist-behavioural approach' within the DSM. Nelson, Yung, Bechdolf and McGorry examine this in context of a phenomenological approach to the understanding of ultra high risk psychiatric disorders. They criticize psychiatric research that addresses subjectivity:

When attempts have been made to address subjectivity, the psychiatric researcher is left without the requisite conceptual tools. Instead, this form of research has tended to live out Abraham Maslow's statement If the only tool you have is a hammer, you tend to treat everything as if it were a nail. That is, the subjective has been approached in operational terms...

'Mad Studies' is an emerging field of study wherein the user movement seeks to reclaim words such as mad and loony and redefine how psychiatry envisages the concept of madness, refuting where user experiences have been co-opted into psychiatric definitions. Mad Studies provides a construct whereby people with 'negative' mental health seek to be identified as part of the neuro-diversity of the human race.

We write at a time when activist concepts such as recovery, inclusion, access and hope have been co-opted, appropriated and politically neutralised by policy-makers, service-providers and government (Costa 2009; McWade 2014; Morgan 2013). User-led services and organisations continue to be most severely affected by spending cuts (Morris 2011), whilst anti-stigma campaigns endorsed by the Royal College of Psychiatrists continue to be pumped with millions of pounds to sell a sanitised version of 'mental health' to the masses (Armstrong 2014). Personalisation has been implemented through a free market ideology that has seen the dispossession and even some deaths of disabled people. It is 'time to talk', and not in the way the establishment wants us to, with individualised and neatly packaged tales of recovery. Instead, let us build upon the rich histories of activism and bring our shared experiences of oppression and marginalisation together[17]

A simple way of looking at it is a slogan adopted by self-advocates 'nothing about us, without us', encouraging educators to co-teach with people who have lived experience of mental illness or distress. A key concept in this ontology is the idea of sanism – a seventh structural oppression to go alongside those associated with race, gender, disability, age, class, and species. It is also defined as Mentalism (discrimination) :

From where we stand, saneism is a devastating form of oppression, often leading to negative stereotyping, discrimination, or arguments that Mad individuals are not fit for professional practice or, indeed, for life (Poole et al., 2012). According to Kalinowski and Risser (2005), saneism also allows for a binary that separates people into a power-up group and a power-down group. The power-up group is assumed to be normal, healthy and capable. The power-down group is assumed to be sick, disabled, unreliable, and, possibly violent. This factional splitting ensures a lower standard of service for the power-down group and allows the power-up group to judge, reframe and belittle the power-down group in pathological terms.[18]

Movement to reconstruct schizophrenia[edit]

Alternative Perception is one of several names suggested by the schizophrenic user movement to replace the term schizophrenia which is on a spectrum of psychotic disorders[19] and is considered to be outmoded by many consumers of services. Several academic authorities, notably Professor Marius Romme founder and principal theorist for the Hearing Voices Movement provide a rationale for the abandonment of this label. A symposium of some of the leading notions in this field from consumers of services and academics concluded:

We are calling for the label of schizophrenia to be abolished as a concept because it is unscientific, stigmatising, and does not address the root causes of serious mental distress. The CASL campaign is driven by two central factors. The concept of schizophrenia is unscientific and has outlived any usefulness it may once have claimed. The label schizophrenia is extremely damaging to those to whom it is applied.[20]

Some scholars of psychology have expressed a need for schizophrenia to be socially reconstructed, including Anne Cooke and Peter Kinderman, who coauthored a paper on the subject.[21]

Historical construction of schizophrenia[edit]

The terms schizophrenia and autism originated from the works of Eugen Bleuler (1857–1939) as different aspects of the same diagnostic condition. Bleuler was a contemporary of Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung. Prior to Bleuler's interventions schizophrenia was referred to as dementia praecox (early insanity) and perceived as a single disorder. Schizophrenia is sometimes also referred to as hebephrenia, stemming in etymology from the Greek god Hebe who was associated with adolescence and as it was thought the onset of schizophrenia came at adolescence. It is generally acknowledged that schizophrenia can have early onset and late onset.

"He first advanced the term schizophrenia in 1908 in a paper based on a study of 647 Burghölzli patients. He then expanded on his paper of 1908 in Dementia Praecox oder Gruppe der Schizophrenie… Bleuler is credited with the introduction of two concepts fundamental to the analysis of schizophrenia: autism, denoting the loss of contact with reality, frequently through indulgence in bizarre fantasy; and ambivalence, denoting the coexistence of mutually exclusive contradictions within the psyche."[22]

Schizophrenia in America is a medical diagnostic category, which in the 1970s was primarily termed differentiated and undifferentiated schizophrenia; international leaders such as R.D. Laing in Europe offered professional expertise in serving this population group. In the context of community mental health services, the broad term mental health also referred to individuals who may have this diagnosis, which may or may not be considered to be valid or relevant. The word schizophrenia is often associated with a "major mental breakdown" in common parlance which may result in the need for psychotherapy, mental health counseling, person-centered therapy,[23] or community support services.[24][25]

Charities committed to changing public perception[edit]

Charities that disagree with the notion of the schizophrenia label in the U.K. include Mind (charity) and Rethink. Mind state on their website "Because of differences of opinion about schizophrenia, it's not easy to identify what might cause it." Mind have previously published an explanatory leaflet, prefaced by Michael Palin that gives a definition of schizophrenia as people "who think outside the normal range of human experience".[26] The National Alliance on Mental Illness says:

"By changing the name, consumers with the symptoms of what actually may be a spectrum of disorders would have a more accurate and descriptive name attached to their diagnosis. Ideally, they would also experience less stigma, as they left behind a name with Greek origins that roughly translates to "shattered mind" and which is often used in popular culture to mean "multiple personality disorder" or "split personality."[27]

Science of schizophrenia and comorbid conditions[edit]

Whilst the definitive cause(s) of schizophrenia remain unknown, research has indicated strong links between genetic make-up, social predisposing factors or stressors and environmental conditions in relation to the development and onset of schizophrenia and other conditions. International geneticists are working towards identifying a gene for Schizophrenia, combined efforts are at the SzGene database. In the course of this research geneticists have identified specific genes or copy number variants or alleles that may explain the comorbidity of various conditions.

Genetic links between comorbid conditions[edit]

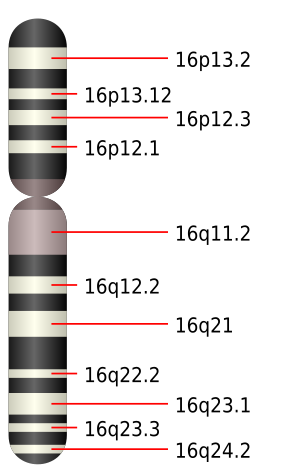

Links between autism and schizophrenia have been studied. From clinical observation, both conditions cause a disruption in normative social functioning which may be mild or severe depending on the individual's position within the spectrum. Social cognition is under-developed in autism and highly developed in psychoses. Four genetic loci are diametrically opposed in terms of diagnoses of autism and schizophrenia, with corresponding deletions for one condition or duplications for the other. Researchers examining chromosome 16 (16p11.2) identified a heredity area on the short arm of human chromosome 16 (16p11.2) which contains microduplication and microdeletion of genome variation. Microduplication of hereditary factors in this heredity area increased the individual's risk of schizophrenia more than 8–14-fold and of autism over 20-fold. A corresponding microdeletion instead of microduplication in the area affected the risk of autism only, but not of schizophrenia.[28][29][30][31] A recent study of de novo mutations - new mutations in people with both autism and schizophrenia spectrum conditions - concluded that schizophrenia and autism are due to "errors" during early organogenesis.[32][33]

The National Institute of Mental Health reported on 8 December 2009 that in spring 2010, major databases on autism research would be joined up to facilitate further research.[34]

Genetic allelles[edit]

Other genetic analysis examines the role of alleles. One study ascribes links between schizophrenia and bipolar disorder by studying a total group of 6909 Europeans, both diagnosed and undiagnosed.[35] Another study suggests that genetic markers may be very dissimilar among different lineages of DNA in people of different cultures, making an international commonality in genetics as a precipitating factor in schizophrenia difficult to identify.[36]

Social factors[edit]

A study published in The Guardian, reported on 9 December 2009, ascribes the onset of the condition to social factors. The authors of the study, which compared 500 patients with mental health problems with other ethnic groups and a control group of 350 people, claim there is an epidemic of schizophrenia amongst the Afro-Caribbean community. They refute the argument that racism may contribute to more diagnoses from psychiatrists of schizophrenia amongst members of the Afro Caribbean community and ascribe more value to deprivation and social isolation as triggering factors in those with a propensity towards schizotype personalities.[37]

Chemical and environmental factors[edit]

Various studies have indicated chemical precipitating factors in the development of autism or schizophrenia and also suggested that environmental factors such as toxins in the air may have precipitated a rise in the number of children born with autism. Ploeger discovered that pre-natal prescribed softenon in the 1960s and '70s led to an increase of children born with autism by 4% as opposed to a usual figure of 0.1%. Sodium valproate, a drug used as an anti-epileptic and as a mood stabilizer, increased the chance of children being born with autism sevenfold. The active component of cannabis (THC) is thought by some to increase the chances of onset of schizophrenia by 2.6 times in its skunk preparation.[38][39][40][41][42] There is no publicly available research on commonalities between these chemicals that may trigger the on/off switches in neuro-receptors linked to genes responsible for conditions on the autistic or schizophrenic spectrum.

Criticism of genetics[edit]

Critique in terms of current genetic research is that there are many candidates for copy number variants that may predispose a likelihood of developing schizophrenia but current research is flawed by both the sample sizes available for analysis by condition population and by an incomplete understanding of 'double whammies' where one allele affects another. [43] This has also been referred to as genetic 'dark matter' with the notion that many rare mutations have not yet been discovered.

Evolution[edit]

Links between autism and schizophrenia have been studied (as above). The implications are both conditions are part of the same spectrum. From clinical observation, both conditions cause a disruption in normative social functioning which may be mild or severe depending on the individual's position within the spectrum. Simon Fraser University researcher Crespi has examined how social cognition is under developed in autism and highly developed in Psychoses and outlines how the relationship between autism and schizophrenic spectrum is not one that has been explored in detail in the latter part of the 20th century. His research hypothesises that the genetic marker for both conditions may lie in the same location. His team have identified four loci that are diametrically opposed in terms of diagnoses of autism and schizophrenia with corresponding deletions for one condition or duplications for the other:

Crespi says the work supports the hypothesis that risks of autism and schizophrenia "have evolved in conjunction with the evolution and elaboration of the human social brain".

Professor Tim Crow, from the University Department of Psychiatry at Oxford University, has long argued that schizophrenia as a condition came about as a result of natural selection. He has argued that schizophrenia is a by-product of the development of language, resulting from an evolutionary change approximately 150,000 years ago, that persisted due to sexual selection. However, conversely to study in polygenes or multiple allele combinations, he maintains that the answer lies in:

the evolutionary history of the Protocadherin11XY gene pair that characterizes the hominin lineage including the 'sapiens' event that represents the transition to modern Homo sapiens.

The use of the RH semantic system may constitute a selective evolutionary advantage allowing the genes predisposing to schizophrenia to proliferate despite the obvious disadvantages of this devastating disease.[45]

Immunology and schizophrenia[edit]

A strand of research into schizophrenia is to investigate the links between viruses that attack the immune system such as herpes and the onset of schizophrenia. Researchers in this field are hopeful that this connection may provide a cure for schizophrenia within the next 20 years.

On the basis of the findings, perspectives for future research are outlined aiming at a precise and consequent strategy to elucidate a potential involvement of immune mechanisms in the etiopathogenesis of schizophrenia.[46]

Muller proposes that the vulnerability-stress model of analysis of schizophrenia should become the vulnerability-stress-inflammation model:

The vulnerability-stress-inflammation model is important as stress may increase proinflammatory cytokines and even contribute to a lasting proinflammatory state. The immune system itself is considered an important further piece in the puzzle, as in autoimmune disorders in general, which are always linked to three factors: genes, the environment and the immune system. Alterations of dopaminergic, serotonergic, noradrenergic and glutamatergic neurotransmission have been shown with low-level neuroinflammation and may directly be involved in the generation of schizophrenic symptoms[47]

Research shows that viral infections of the immune system can dramatically increase the frequency of the onset of schizophrenia.

a large scale Danish nationwide study on 39,076 persons with a diagnosis of schizophrenia spectrum disorders showed that the history of hospitalisation with infection increased the risk of schizophrenia by 60%[48]

Global moves to change the construction of schizophrenia[edit]

Netherlands[edit]

In the Netherlands alternative proposals for the name schizophrenia include dysfunctional perception syndrome[49] and Salience Syndrome :

The concept of 'salience' has the potential to make the public recognize psychosis as relating to an aspect of human mentation and experience that is universal. It is proposed to introduce, analogous to the functional-descriptive term 'Metabolic syndrome', the diagnosis of 'Salience syndrome' to replace all current diagnostic categories of psychotic disorders. Within Salience syndrome, three subcategories may be identified, based on scientific evidence of relatively valid and specific contrasts, named Salience syndrome with affective expression, Salience syndrome with developmental expression and Salience syndrome not otherwise specified.[50]

From a social model of disability perspective, this interlinks:

The human mind has the ability to turn its attention to something that is salient, something that jumps out at you. We then focus on it. In some people this function is disturbed, and everything gets an enormous significance. They think, for example, that a television programme is about them, or that people who are just walking along the street are out to harm them. Research shows that this can happen to everybody under the influence of drugs, also to healthy people. The word syndrome indicates that it is about a cluster of symptoms. And not about a clearly defined illness.[51]

Japan[edit]

In Japan:

In order to contribute to reduce the stigma related to schizophrenia and to improve clinical practice in the management of the disorder, the Japanese Society of Psychiatry and Neurology changed in 2002 the old term for the disorder, Seishin Bunretsu Byo ("mind-split-disease"), into the new term of Togo Shitcho Sho ("integration disorder")...Eighty-six percent of psychiatrists in the Miyagi prefecture found the new term more suitable to inform patients of the diagnosis as well as to explain the modern concept of the disorder."[52]

The Japanese society of psychiatry and neurology report:

This change is making psychoeducation much easier and is being useful to reduce misunderstandings about the illness and to decrease the stigma related to schizophrenia. The new term has been officially accepted by the Japanese medicine and media and is being adopted in the legislation in 2005.[53]

South Korea[edit]

In South Korea, schizophrenia has been renamed to 'Attunement Disorder':

a new term, "Johyeonbyung (attunement disorder)", was coined in South Korea. This term literally refers to tuning a string instrument, and metaphorically it describes schizophrenia as a disorder caused by mistuning of the brain's neural network.[54]

See also[edit]

Other articles of the topic Society : Social Activist, Gamer

Some use of "" in your query was not closed by a matching "".Some use of "" in your query was not closed by a matching "".

References[edit]

- ↑ Walker MT (2006). "The Social Construction of Mental Illness and its Implications for the Recovery Model". International Journal of Psychosocial Rehabilitation. 10 (1): 71–87.

- ↑ Mary Barnes; Joseph H. Berke (17 March 2002). Mary Barnes: two accounts of a journey through madness. Other Press, LLC. ISBN 978-1-59051-016-2. Retrieved 23 October 2010. Search this book on

- ↑ Roberts GA (2000). "Narrative and severe mental illness:what place do stories have in an evidence-based world?". Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 6 (6): 432–441. doi:10.1192/apt.6.6.432.

- ↑ Noll, Richard (1983). "Shamanism and Schizophrenia.A State-Specific approach to the 'Schizophrenia Metaphor of shamanic states'". American Ethnologist. 10 (3): 443–459. doi:10.1525/ae.1983.10.3.02a00030. JSTOR 644263.

- ↑ Sapolsky, Robert M. (1998). "Circling the Blanket for God". The Trouble with Testosterone: and Other Essays on the Biology of the Human Predicament. New York: A Touchstone Book, Simon & Schuster. pp. 247–249. ISBN 978-0-684-83409-2. Search this book on

- ↑ Sapolsky, Robert (April 2003). "Belief and Biology". Freedom from Religion Foundation. Retrieved August 20, 2023.

- ↑ "Dr. Robert Sapolsky's lecture about Biological Underpinnings of Religiosity".

- ↑ Boyle, M., 2002, "Schizophrenia: A Scientific Delusion"

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Walker, Michael (2006). "The social construction of mental illness and its implications for the recovery model" (PDF). Internanational Journal of Psychosocial Rehabilitation. 10 (1): 71–87. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 February 2015. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ Brown, Phil (1995). "Naming and Framing: The Social construction of Diagnosis and Illness" (PDF). Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 35 (extra issue): 34–52. doi:10.2307/2626956. JSTOR 2626956. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 July 2011. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ Conrad, Peter (1992). "Medicalization and social control" (PDF). Annual Review of Sociology. 18: 209–232. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.18.1.209.

- ↑ Conrad, P.; Kristen, K.. (2010). "The social construction of illness, key insights and policy implications". Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 51 (1): S67–S69. doi:10.1177/0022146510383495. PMID 20943584. Unknown parameter

|s2cid=ignored (help) - ↑ Foucault, M. (1973), The Birth of the Clinic: An Archaeology of Medical Perception (PDF), Tavistock publications limited, retrieved 14 November 2015

- ↑ Report of the Royal Commission on the law relating to mental illness and mental deficiency (Report). UK. 1957.

- ↑ UK Parliament (2015). Tackling social stigma on mental health: Key issues for the 2015 Parliament (Report).

- ↑ Nelson, B.; Yung, A. R.; Bechdolf, A.; McGorry, P. D. (2007-04-09). "The Phenomenological Critique and Self-disturbance: Implications for Ultra-High Risk ("Prodrome") Research". Schizophrenia Bulletin. Oxford University Press (OUP). 34 (2): 381–392. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbm094. ISSN 0586-7614. PMC 2632406. PMID 17702990.

- ↑ Mcwade; Milton; Beresford (2015). "Mad studies and neurodiversity: a dialogue" (PDF). Disability & Society. 30 (2): 71–87. doi:10.1080/09687599.2014.1000512. Unknown parameter

|s2cid=ignored (help) - ↑ LeFrançois, B.; Menzies, R. (2013), "Breaking open the bone", Mad Matters: A Critical Reader in Canadian Mad Studies, Canadian Scholars press, pp. 96–97, ISBN 9781551305349

- ↑ Ahmed, Iqbal; Fujii, Daryl (2007). The spectrum of psychotic disorders: neurobiology, etiology, and pathogenesis. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-85056-8. Search this book on

[page needed]

[page needed]

- ↑ "caslcampaign.com". Retrieved 11 September 2016.

- ↑ Cooke, Anne. "Alternatives to the Disease Model Approach to Schizophrenia". Journals.Sagepub.com. Journal of Humanistic Psychology. doi:10.1177/0022167817745621. Retrieved 9 February 2021. Unknown parameter

|s2cid=ignored (help) - ↑ "Eugen Bleuler, Swiss psychiatrist". Britannica. Retrieved 11 September 2016.

- ↑ B. T., Brodley (2011). "The nondirective attitude in client-centered therapy". In Moon, K.A.; Witty, M.; Grant, B.; Rice, B. Practicing Client-Centered Therapy. Ross-on-Rye, Herefordshire, UK: PCCS. Search this book on

Originally published as Brodley, B. T. (1997). "The nondirective attitude in client-centered therapy". The Person-Centered Journal. 4 (1): 18–30.

Originally published as Brodley, B. T. (1997). "The nondirective attitude in client-centered therapy". The Person-Centered Journal. 4 (1): 18–30.

- ↑ Dougherty, S. (2002). "Supported education in a clubhouse setting". In Mowbray, C.; Brown, K.S.; Furlong-Norman, K.; Soydan, A.S. Supported Education and Psychiatric Rehabilitation: Models and Methods. Linthicium, MD: International Association of Psychosocial Rehabilitation Services. pp. 139–146. Search this book on

- ↑ Carling, P.J. (1995). "Ch. 8: Creating employment opportunities". Return to Community: Building Support Systems for People with Psychiatric Disabilities. New York, NY: The Guilford Press. pp. 227–248. Search this book on

- ↑ "Schizophrenia". Mind. Retrieved 11 September 2016.

- ↑ Berg, Stacie Z. (2006). "Changing the 'S' Word: Is There a Better Name?". NAMI: The National Alliance on Mental Illness. Archived from the original on 17 November 2006. Retrieved 11 September 2016. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ Crespi, B.; Badcock, C. (2008). "Psychosis and autism as diametrical disorders of the social brain" (PDF). Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 31 (3): 241–261, discussion 261–320. doi:10.1017/S0140525X08004214. PMID 18578904.

- ↑ "Research backs theory on autism, schizophrenia". physorg.com. Retrieved 9 December 2009.

- ↑ McCarthy SE, Makarov V, Kirov G, et al. (November 2009). "Microduplications of 16p11.2 are associated with schizophrenia". Nature Genetics. 41 (11): 1223–7. doi:10.1038/ng.474. PMC 2951180. PMID 19855392.

- ↑ Kumar RA, KaraMohamed S, Sudi J, et al. (February 2008). "Recurrent 16p11.2 microdeletions in autism". Human Molecular Genetics. 17 (4): 628–38. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddm376. PMID 18156158.

- ↑ Awadalla, P.; Gauthier, J.; Myers, R. A.; Casals, F.; Hamdan, F. F.; Griffing, A. R.; Côté, M.; Henrion, E.; Spiegelman, D.; Tarabeux, J.; Piton, A. L.; Yang, Y.; Boyko, A.; Bustamante, C.; Xiong, L.; Rapoport, J. L.; Addington, A. M.; Delisi, J. L. E.; Krebs, M. O.; Joober, R.; Millet, B.; Fombonne, É.; Mottron, L.; Zilversmit, M.; Keebler, J.; Daoud, H.; Marineau, C.; Roy-Gagnon, M. H. L. N.; Dubé, M. P.; Eyre-Walker, A. (2010). "Direct Measure of the De Novo Mutation Rate in Autism and Schizophrenia Cohorts" (PDF). The American Journal of Human Genetics. 87 (3): 316–24. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.07.019. PMC 2933353. PMID 20797689. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 July 2011. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ Ploeger Thesis Summation

- ↑ Major Databases Link Up to Advance Autism Research, retrieved 12 December 2009

- ↑ Purcell SM, Wray NR, Stone JL, et al. (2009). "Common polygenic variation contributes to risk of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder". Nature. 460 (7256): 748–52. Bibcode:2009Natur.460..748P. doi:10.1038/nature08185. PMC 3912837. PMID 19571811.

- ↑ McClellan JM, Susser E, King MC (2007). "Schizophrenia: a common disease caused by multiple rare alleles". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 190 (3): 194–9. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.106.025585. PMID 17329737.

- ↑ Lewin, Matthew (8 December 2009). "Schizophrenia 'epidemic' among African Caribbeans spurs prevention policy change". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 September 2016.

- ↑ "Epilepsy drug may increase risk of autism in children". Retrieved 11 September 2016.

- ↑ "Autism and schizophrenia share common origin". Retrieved 11 September 2016.

- ↑ "Study shows California's autism increase not due to better counting, diagnosis". Retrieved 11 September 2016.

- ↑ Boseley, Sarah (30 November 2009). "Skunk users face greater risk of psychosis, researchers warn". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 September 2016.

- ↑ Nutt, David (2 November 2009). "David Nutt: my views on drugs classification". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 September 2016.

- ↑ "CNV 'Double Whammies' May Account for Variable Neuropsychiatric Phenotypes". schizophreniaforum.org. Archived from the original on 29 November 2010. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ "Clues to the origin of language?". Archived from the original on 25 September 2008. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ Leonhard, Dirk; Brugger, Peter (October 1998). "Creative, Paranormal, and Delusional Thought: A Consequence...: Cognitive and Behavioral Neurology". Cognitive and Behavioral Neurology. 11 (4): 177. Retrieved 11 September 2016.

- ↑ Rothermund, M.; Volker, A.; Bayer, T. (2001). "Review of Immunological and Immunopathological Findings in Schizophrenia". Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 15 (4): 319–339. doi:10.1006/brbi.2001.0648. PMID 11782102. Unknown parameter

|s2cid=ignored (help) - ↑ Muller, N. (2014). "Immunology of Schizophrenia" (PDF). Neuroimmunomodulation. 21 (2–3): 109–116. doi:10.1159/000356538. PMID 24557043. Unknown parameter

|s2cid=ignored (help) - ↑ Norbert Muller; Aye-Mu Myint; Markus J. Schwarz (2011). "Immunology and psychiatry: from basic research to therapeutic interventions". Current Topics in Neurotoxicity. 8: 194–9.

- ↑ "Schizophrenia Now Called "Dysfunctional Perception Syndrome"". 9 October 2009. Retrieved 11 September 2016.

- ↑ van Os, J (2009). "'Salience syndrome' replaces 'schizophrenia' in DSM-V and ICD-11: psychiatry's evidence-based entry into the 21st century?". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 120 (5): 363–72. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01456.x. PMID 19807717.

- ↑ Mol, S. (2009). "'Dysfunctional Perception Syndrome': The new name for schizophrenia?" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 August 2010. Retrieved 21 October 2010. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ Sato M (2006). "Renaming schizophrenia: a Japanese perspective". World Psychiatry. 5 (1): 53–55. PMC 1472254. PMID 16757998.

- ↑ SATO M (2005). "The Yokohama Declaration: an update". World Psychiatry. 4 (1): 60–61. PMC 1414727.

- ↑ Lee, Y.S.; et al. (2014). "Johyeonbyung (attunement disorder): Renaming mind splitting disorder as a way to reduce stigma of patients with schizophrenia in Korea". Asian Journal of Psychiatry. 8: 118–120. doi:10.1016/j.ajp.2014.01.008. PMID 24655643.

External links[edit]

This article "Social construction of schizophrenia" is from Wikipedia. The list of its authors can be seen in its historical and/or the page Edithistory:Social construction of schizophrenia. Articles copied from Draft Namespace on Wikipedia could be seen on the Draft Namespace of Wikipedia and not main one.