The Myth of the Zodiac Killer

| File:The Myth of the Zodiac Killer.jpg | |

| Author | Thomas Henry Horan |

|---|---|

| Illustrator | |

| Cover artist | Thomas Henry Horan |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Subject | Zodiac Killer |

| Genre | True crime |

| Published | 2014 |

| Publisher | Self-published |

| Pages | 330 |

| ISBN | 979-8601798327 Search this book on |

The Myth of the Zodiac Killer: A Literary Investigation is a self-published, 2014 book by Thomas Henry Horan. It advances a novel theory and cultural analysis about the Zodiac Killer which suggests that no such serial killer actually existed. According to Horan's thesis, attacks attributed to a Zodiac Killer were unrelated homicides and assaults. The person who took credit for the attacks was, according to Horan, a hoaxer with inside access to police files, possibly a police officer or journalist. The hoaxer used his access to create a believable narrative linking actual, unsolved murders to a fictional character he created.

While some critics have lauded the hypothesis presented in the book, it is considered unpopular among the community of amateur sleuths that has grown-up around the Zodiac mystery. Its unpopularity has been attributed by some to its attack on what has become a narrative orthodoxy with respect to the unsolved killings.

Background[edit]

Subject[edit]

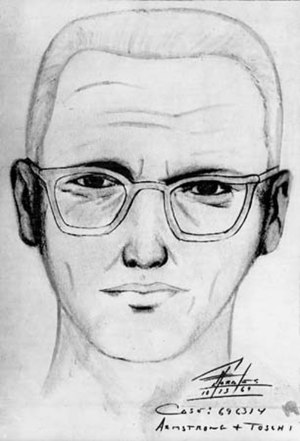

Zodiac is the self-assumed name of a person or persons who wrote several letters to San Francisco-area newspapers in the late 1960s and early 1970s – as well as to celebrity attorney Melvin Belli – in which he took credit for the murders of 37 people.[lower-alpha 1] The letter writer also threatened to bomb a school bus, to launch a wave of sniper attacks, and to assassinate journalist Paul Avery. The incident created panic in the San Francisco Bay area, and led to citywide curfews and a multi-jurisdiction manhunt for the culprit. The Zodiac killings have been described as one of the most notorious crime sprees in American history and were the subject of two bestselling books by Robert Graysmith, as well as a 2007 film directed by David Fincher; they also served as the inspiration for the 1971 thriller film Dirty Harry. As of 2020, no arrests have been made, though the case is still the subject of an open investigation by the San Francisco Police Department, and other law enforcement agencies.[2]

Writing[edit]

According to Thomas Henry Horan, a retired English composition instructor at a St. Louis community college and former private investigator, he had been interested in the Zodiac Killer from the perspective of the writing style and structure of the Zodiac letters.[3] During his study, original police case files became available.[3] Upon reviewing the files, Horan said, "I couldn't help notice that the books Robert Graysmith had written [about the Zodiac] were mostly false and, by following up the trail of falsehoods in those books, I came straight to a person who had the knowledge to write the Zodiac letters. And, he had handwriting which is a perfect match for the handwriting on the Zodiac Killer letters."[3]

In the early 2010s, Horan wrote and self-published three short books detailing his findings, which he republished in 2014 as a single, 330-page volume, The Myth of the Zodiac Killer: A Literary Investigation.[3]

The book is dedicated to "the victims and their families — who never got any justice".[4]

Contents[edit]

Horan's thesis is that the several attacks attributed to a "Zodiac Killer" were actually unrelated, or largely unrelated, criminal incidents, and that the author of the attribution letters sent to San Francisco-area newspapers had nothing to do with any of them, but was potentially a police officer.[4] In the book, Horan names the law enforcement officer he alleges is responsible for the letter writing campaign – a police forensics specialist who had once worked as a newspaper reporter and who had previously been exposed to a Melanesian supernatural belief similar to one communicated by the Zodiac writer.[4] He also theorizes that a second writer, a journalist whom he names, independently wrote several additional Zodiac letters in the 1970s, though not in coordination with the first writer.[4]

According to Horan, the Zodiac-attributed attacks had little physical evidence and no modus operandi to link them with each other. The existence of a serial killer was only established through the attribution letters mailed to newspapers, without which the crimes might have been dealt with as separate events by police. Horan contends that, once established, the "myth" of a Zodiac Killer was fueled by the zealousness of the San Francisco Chronicle – recipient of most of the Zodiac letters – which, at the time, had a reputation for sensationalism and tabloid-style journalism.[4]

Allegation of insider source of Zodiac letters[edit]

Key to Horan's contention that the author of the Zodiac letters was not the same person responsible for Zodiac-attributed murders is his observation that the Zodiac letters contained erroneous information about crime scenes that had been recorded in police reports but which was later proved wrong.[4] For instance, in the first series of Zodiac letters, the letter writer claims to have shot the Blue Rock Springs survivor in the knee, an observation recorded in the report of the responding officer.[4] However, according to Horan, the responding officer erred in his initial report as the survivor had not actually sustained a bullet wound to the knee.[4] Horan says this, and similar inconsistencies, demonstrates that the Zodiac letter writer had access to police files but had never actually been present at the crime scenes.[4]

Horan also notes that the Zodiac writer, on several occasions, attempted to take credit for attacks which were later solved or attributed to others.[4] He also notes writing similarities common between some of the police reports and the Zodiac letters.[4]

Deconstruction of linkages between Zodiac-attributed attacks[edit]

Horan deconstructs the linkages between the four attacks generally agreed by law enforcement to have been perpetrated by a Zodiac Killer.[lower-alpha 2] He contends that these attacks, if not for the Zodiac letters, would have nothing else to link them to each other as no fingerprints or conventional physical evidence was recovered at the crime scenes and no pattern between attacks was observed.[4][lower-alpha 3]

Lake Herman Road attack[edit]

The first Zodiac-attributed attack was the murder of David Faraday and Betty Lou Jensen on Lake Herman Road, an attack which the letter writer did not credit himself with for more than a year, until after the Blue Rock Springs attack.[2]

According to Horan, the Lake Herman Road killings occurred in the midst of a string of drug-related murders in the area.[4] Prior to the Blue Rock Springs attack, Horan reports, Solano County Sheriff's Office detective Terry Cunningham had received information from an informant that two members of a local gang, later jailed on unrelated charges, confessed to the killings of Faraday and Jensen, however, the investigating officer didn't find the confession credible.[4][lower-alpha 4]

Blue Rock Springs attack[edit]

Horan challenges the testimony given by the Blue Rock Springs survivor that he had been on a social outing with the other victim, Darlene Ferrin, when they were approached by a man unknown to him who – without warning – shot them both.[4]

According to Horan, the site of the Blue Rock Springs attack has been described as a "lover's lane" by media, however, based on his interviews with retired police officers who worked in the area was better known among them as a location of criminal activity where illegal drugs were bought and sold as part of what was, at the time, a growing meth industry violently controlled by the Hells Angels.[4] Horan notes that the survivor had a criminal record and, at the time of the attack, was wearing three sweaters despite the temperature outside being above eighty degrees, indicating he was "dressed for burglary".[4][lower-alpha 5] According to Horan, wearing layered clothing is a tactic used by burglars to allow them to quickly change their appearance.[4][lower-alpha 6] Horan posits, therefore, that the survivor may have been involved in a questionable transaction of some type that resulted in him being targeted by a criminal, and not as part of a serial killing.[4] He goes on to deconstruct the attribution telephone call received by emergency dispatchers after the attack, presenting an argument as to why it may have been misrepresented and misreported.[4]

Lake Berryesea attack[edit]

Lake Berryesea is the only known occasion at which the Zodiac costume – consisting of a black, "ceremonial-type" hood with gun sight symbol – was observed.[4] It is also the only attack at which the "Zodiac Killer" left an attribution note at the crime scene itself, scrawling it into the side of victim Brian Hartnell's Volkswagen auto.[4]

Horan suggests this attack could be explained by a copycat who had been inspired by the lurid stories he had read about the preceding murders in the San Francisco Chronicle, but was not himself the letter writer or the perpetrator of the other attacks.[4][lower-alpha 7] Horan notes that the attribution note left at the scene was not signed "Zodiac".[4] While the letter writer had previously identified himself with this name, published media reports at the time referred to him as the "Code Killer" and "Zodiac Killer" had yet to enter the lexicon.[4]

Presidio Heights attack[edit]

In disconnecting the Presidio Heights attack – the murder of taxi driver Paul Stine – from previous attacks, Horan notes that the description given of the attacker by witnesses differed from the description provided of the perpetrator of the earlier murders.[4] In the case of the Presidio Heights attack, the perpetrator was gaunt; at Blue Rock Springs and Lake Berryesea he was stocky.[4] This was also the only Zodiac-attributed killing to involve a single victim, instead of a male/female couple, and the only one which occurred in the City and County of San Francisco.[4]

Horan notes that all the details of the Stine attack led police to believe it was nothing more than a routine cab robbery gone wrong, and it was only connected to a Zodiac Killer after the San Francisco Chronicle received an attribution letter a week after the fact.[4] In the attribution letter sent after the Presidio Heights attack, the Zodiac writer included a torn piece of Stine's bloodied shirt, the only time a "souvenir" was included by Zodiac in his letters.[4] According to Horan, police reports of the crime scene do not mention Stine's shirt as having been ripped, which he says suggests that strips from it were torn off only after it was taken into evidence, presumably by someone with access to the SFPD's evidence room.[4]

Critical reception[edit]

In MEL Magazine, Bill Black wrote that Horan's book was "utterly compelling," but noted that Zodiac enthusiasts likened Horan to a "creationist, a flat-earther, a circus barker".[10]

Writing for ABC, Israel Viana described the theories advanced in Horan's book as among "the most unpopular" within the community of Zodiac enthusiasts, an observation repeated by El Confidencial's Héctor Barnés.[11][12] According to Barnés, the incredulity with which Horan's work has been met by the community of Zodiac enthusiasts and amateur investigators is due to the fact that, if true, it would effectively end a hobby shared by thousands of internet sleuths and weekend detectives.[12]

Horan has appeared on three episodes of the Generation Why podcast, which reviewed the several books republished as The Myth of the Zodiac Killer: A Literary Investigation as "interesting reads".[3] Mike Ferguson of the Criminology podcast described the book's thesis as "not a really legitimate theory".[13]

See also[edit]

- Henry Lee Lucas – Texas fabulist aided by police in falsely confessing to more than 100 unsolved murders

Notes[edit]

- ↑ Police have only linked seven murders and attempted murders to Zodiac.[1]

- ↑ The 1966 murder of Cheri Jo Bates in Riverside, California, though linked by some sources to Zodiac, has been discredited by investigators with the Riverside Police Department.[5]

- ↑ Most attacks by serial killers target a specific demographic (e.g. women, children, etc.) and use a specific weapon type (e.g. gunshot, knife, etc.).[6] Zodiac-attributed killings, had – according to CourtTV – "no modus operandi, no pattern in the victims".[7]

- ↑ In the 1990s, retired Vallejo police detective John Lynch – who was among the original investigators of the attack – said he felt Faraday had been targeted as he had learned of a major drug deal and that a serial killer was not responsible for the murders.[8]

- ↑ The survivor has explained his decision to wear multiple layers of clothing as part of an attempt to look larger than he was, explaining he was self-conscious about his thin frame.[2]

- ↑ The use of a "burglar's outfit" has been observed by police in other crimes; for instance, in a 2016 burglary in Palo Alto, California, police allege a suspect discarded outer layers of clothing resulting in the false belief that there were multiple perpetrators to the crime.[9]

- ↑ The phenomenon of Zodiac-inspired copycats has been recorded in at least two other cases: Heriberto Seda and Shinichiro Azuma.

References[edit]

- ↑ "Zodiac Killer: Code-breakers solve San Francisco killer's cipher". BBC News. December 12, 2020. Retrieved December 19, 2020.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 "Zodiac Killer". biography.com. Biography. Retrieved December 19, 2020.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 "The Zodiac Killer Hoax of 1986 – 125". Generation Why. Wondery. June 9, 2015. Retrieved December 18, 2020.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 4.14 4.15 4.16 4.17 4.18 4.19 4.20 4.21 4.22 4.23 4.24 4.25 4.26 4.27 4.28 4.29 4.30 Horan, Thomas Henry (2014). The Myth of the Zodiac Killer: A Literary Investigation. Search this book on

- ↑ Butterfield, Michael. "The Zodiac Killer: A Timeline". history.com. History Channel. Retrieved December 17, 2020.

- ↑ Bonn, Scott (June 29, 2015). "Serial Killers: Modus Operandi, Signature, Staging & Posing". Psychology Today. Retrieved December 17, 2020.

- ↑ "Famous cold cases: Police nemeses, tabloid fodder". CNN. CourtTV. December 10, 2007. Retrieved December 17, 2020.

- ↑ "Zodiac Killer". zodiackiller.com. Retrieved December 21, 2020.

- ↑ Lee, Jacqueline (December 18, 2020). "Camera shows Palo Alto residential burglar biking away with loot". San Jose Mercury News. Retrieved October 4, 2016.

- ↑ Black, Bill (2018). "This Eccentric Academic Thinks the Zodiac Killer is a Hoax". MEL Magazine. Retrieved December 19, 2020.

- ↑ Viana, Israel (September 3, 2020). "El Asesino del Zodiaco: ¿se ha descubierto por fin la identidad del mayor psicópata de la historia?". ABC (in español). Retrieved December 19, 2020.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Barnés, Héctor (December 20, 2018). "El mayor asesino en serie de la historia no existió nunca: una teoría que lo explica todo". El Confidencial (in español). Retrieved December 18, 2020.

- ↑ Ferguson, Michael (2018). The Case of the Zodiac Killer. Denver: WildBlue Press. p. 113. ISBN 978-1-947290-52-5. Search this book on

This article "The Myth of the Zodiac Killer" is from Wikipedia. The list of its authors can be seen in its historical and/or the page Edithistory:The Myth of the Zodiac Killer. Articles copied from Draft Namespace on Wikipedia could be seen on the Draft Namespace of Wikipedia and not main one.