Alexander Hamilton and slavery

Some of this article's listed sources may not be reliable. (July 2018) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

| This article may lend undue weight to certain ideas, incidents, or controversies. (July 2018) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

The relationship between Alexander Hamilton and slavery is a matter of some historical contention. A substantial majority of Hamilton's biographers characterize him as an abolitionist, emphasizing his activities against slavery, examples of which include co-founding the New York Manumission Society, serving as its second president, and defending the rights of free blacks in the New York courts. Other writers have argued for a less-favorable point of view, emphasizing that members of Hamilton's family owned slaves, and pointing out that Hamilton was involved in transactions for the purchase, sale, and transfer of slaves on behalf of family members and legal clients.

It is generally agreed by historians that Hamilton never owned any slaves himself. A number of contrary sources rely primarily on a biography by Allan McLane Hamilton, one of Hamilton's grandsons, who cited entries in business ledgers showing the purchase of slaves and interpreted those purchases as having been for Hamilton himself rather than for a client.[1]

On the abolition of slavery[edit]

Until recently the prevailing scholarly view was that Hamilton, like the Founders generally, lacked a deep concern about slavery. John Patrick Diggins traced this animus of historians against Hamilton to Vernon L. Parrington, who, writing in the 1920s to praise Jefferson and the Enlightenment, denounced Hamilton as a reactionary and unenlightened, greedy and evil.[2] Sean Wilentz contends that the consensus has changed sharply in Hamilton's favor in recent years.[3] For example, Michael D. Chan argues that the first U. S. Treasury Secretary was committed to ending slavery,[4] Chernow calls him "a fervent abolitionist",[5]:629 David O. Stewart states he was a "lifelong opponent of slavery",[6] and Jerome Braun says he "was a leading anti-slavery advocate".[7] Historian Manning Marable says Hamilton "vigorously opposed the slave trade and slavery's expansion."[8]

On the other hand, history professor Michelle DuRoss accuses these biographers of "overstat[ing] Hamilton's stance on slavery."[9][10] Writes DuRoss,

Hamilton's position on slavery is more complex than his biographers' suggest. Hamilton was not an advocate of slavery, but when the issue of slavery came into conflict with his personal ambitions, his belief in property rights, or his belief of what would promote America's interests, Hamilton chose those goals over opposing slavery. In the instances where Hamilton supported granting freedom to blacks, his primary motive was based more on practical concerns rather than an ideological view of slavery as immoral. Hamilton's decisions show that his desire for the abolition of slavery was not his priority. One of Alexander Hamilton's main goals in life was to rise to a higher position in society. […] When Hamilton had to make a choice between his social ambitions and his desire to free slaves, he opted to follow his ambitions.[9][10]

Historian Phillip W. Magness agrees that a

striking feature of the Hamiltonian corpus is the general absence of any clear, unequivocal exposition of the "abolitionist" viewpoint so many of his biographers have attributed to him. In this respect, he stands in marked contrast to other prominent antislavery men of his era who wrote extensively on the subject. Consider John Adams, who despite compromising on the issue to retain the southern states in the nascent republic, made his moral objections to slavery clearly known. Or compare Hamilton's silence to Benjamin Franklin, a slave-owner in his younger days who converted to the abolitionist cause and became an outspoken antislavery man by the end of his life. One might even look to Thomas Jefferson, owner of a large Virginia plantation who nonetheless wrote multiple works conceding the immorality of the institution and expressing his fears of what its future entailed for the United States.; Hamilton, by contrast, seldom even referred to slavery in his writings beyond an abstract generalization and never approached the specificity of many of his contemporaries in engaging the subject.[11][12]

Black American poet and essayist Ishmael Reed accuses establishment historians of "whitewash[ing]" history,[13] of being "guilty of a cover-up" for "smudg[ing] over if not ignor[ing] altogether" the "cruel actions of the Founding Fathers," of "serv[ing] as lackeys for famous, wealthy white men".[10] This is the case, he writes, "with Alexander Hamilton whose life has been scrubbed with a kind of historical Ajax until it sparkles. His reputation has been shored up as an abolitionist and someone who was opposed to slavery. Not true." Magness sums up, "Hamilton's relationship with slavery is far from unblemished."[11]

Reference to slavery in polemics[edit]

Hamilton's polemic first against King George's ministers contains a paragraph that speaks of the evils that "slavery" to the British would bring upon the Americans. McDonald sees this as an attack on the institution of slavery. David Hackett Fischer believes the term is used in a symbolic way at that time.[14][note 1]

Hamilton and John Laurens on slaves in the Continental Army[edit]

During the Revolutionary War, Hamilton took the lead in proposals to grant freedom to slaves if they joined the Continental Army and to compensate their masters for their loss. In 1779, South Carolina desperately needed soldiers to fight in the Continental Army, and Hamilton, like his friend John Laurens of South Carolina, saw this as the only practical solution to the army's problems.[9][12] That year, Hamilton and Laurens worked to propose that such a unit be formed under Laurens's command.[9] Hamilton proposed to the Continental Congress that it create up to four battalions of slaves for combat duty, and free them. Hamilton wrote to John Jay, then president of the Continental Congress, arguing that they had to offer black soldiers freedom as it would prove the only means by which to keep them loyal.[9][11][12] Congress recommended that South Carolina (and Georgia) acquire up to three thousand slaves for service, if they saw fit. Although the South Carolina governor and Congressional delegation had supported the plan in Philadelphia, they did not implement it.[15] [note 2]

Hamilton believed that the natural faculties of blacks were probably as good as those of free whites, and he warned that the British would arm the slaves if the patriots did not, in which case the slaveholders would lose their property in slaves without any benefit.[9] In his 21st-century biography, Chernow cites this incident as evidence that Hamilton and Laurens saw the Revolution and the struggle against slavery as inseparable.[5]:121 [16] Hamilton attacked his political opponents as demanding freedom for themselves and refusing to allow it to blacks.[17] Historian DuRoss, however, says that this completely ignores Hamilton's actual motivation for supporting Laurens's plan. As DuRoss puts it, "Hamilton was motivated by practical terms more so than any ideology that espoused the equality of the races. That is not to say that Hamilton viewed the races as innately unequal, but that it did not dictate Hamilton's positions on policy. Hamilton, like Laurens, wanted to allow blacks into the army because they thought it was the only practical solution to the army's problems."[9]

Membership in the New York Manumission Society[edit]

In January 1785, Hamilton attended the second meeting of the New York Manumission Society (NYMS). John Jay was president and Hamilton was the first secretary and later became president.[18] Nevertheless, his attendance at meetings was sporadic at best,[9] and since the Society's records lack substantial information about Hamilton, DuRoss believes this suggests Hamilton did not play a dominant role in the society.[9][12] "Moreover," DuRoss writes, "the records of the Manumissions Society, along with Hamilton's papers, lack any real discussion from Hamilton regarding his thoughts on the society or what the society should strive to achieve."[9] The society was not abolitionist in the strict sense of the term, but was, rather, a "moderate and gradualist organization" at best.[11] In comparing it to the anti-slavery society in Pennsylvania which explicitly pushed for the abolition of slavery, DuRoss notes that "the anti-slavery society Hamilton belonged to advocated the manumission of slaves [emphasis added]. The Society said that people should free their slaves, not that they should have to free their slaves" [emphasis in original].[9] Despite being a manumission society, members were not even required to manumit their own slaves.[9][12]

Chernow notes how the membership soon included many of Hamilton's friends and associates, and DuRoss notes how his membership gave him the opportunity to "further interact with the top of New York society," thereby aiding him in his social ambition, in further "climb[ing] the social latter."[9][12] Hamilton was a member of the committee of the society that petitioned the legislature to end the slave trade, and that succeeded in passing legislation banning the export of slaves from New York.[5]:216 Hamilton himself, however, never proposed any legislation to curtail slavery,[19] and "his record from the 1790s until his death in 1804 includes little to no action against" it.[13] Further, New York Evening Post, which Hamilton founded, contained advertisements for the renting out of slaves, leading DuRoss to comment that if Hamilton was opposed to slavery, "it is reasonable to assume he could have prevented the printing of advertisements in his newspaper two years after the law was passed."[9]

In the same period he was a member of the manumission society, Hamilton felt bound by the rule of law of the time and his law practice facilitated the return of a fugitive slave to Henry Laurens of South Carolina.[20] He opposed the compromise at the 1787 Constitutional Convention by which the federal government could not abolish the slave trade for 20 years, and was disappointed when he lost that argument.[5]:239 But, according to Stewart, he also persuaded abolitionist New Yorkers to refrain from petitioning the Convention to support abolition,[6] and he likewise supported the three-fifths clause that served to increase the representative power of the South's slaveholding aristocracy as he believed "that the more property one has, the more his vote should count."[6][9][12] Further, Hamilton and James Wilson advocated having this clause apply to representation in both houses of Congress, not merely the House of Representatives.[6]

On the Treaty of Paris (1783)[edit]

Hamilton initially supported forced emigration, and consequentially reënslavement, for American slaves freed by the British in the Revolutionary War,[9][21] but he soon backed away from this position as he did not wish to risk reigniting war with Great Britain.[9] His only concern in this matter was "the cause of national honor, safety and advantage."[22][23]

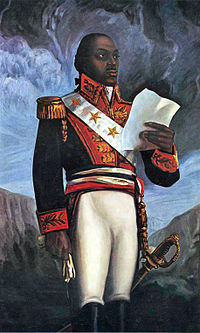

On the Haitian Revolution[edit]

Horton has argued from this that he would be comfortable with a multiracial society, and that this distinguished him from his contemporaries.[24] In international affairs, Hamilton reluctantly accepted Toussaint L'Ouverture's black government in Haiti after the slave revolt that overthrew French control, as he had supported aid to the slaveowners in 1791—both measures hurt France.[25] Hamilton's reaction, observes DuRoss, "was not the reaction of an abolitionist wishing to see blacks free. Instead of sympathizing with the black slaves on the island, Hamilton sympathized with their owners."[23] Although he regarded the slave revolt a "misfortune",[23][26] a "calamitous event" that he "[r]egrett[ed] most sincerely",[23][27] and although he wanted the United States to refrain from making formal treaties with, or being committed to, the independence of Saint-Domingue (which he often referred to as "Saint Domingo"),[23][28] Hamilton did want to ensure continued trade with Saint-Domingue as well as protection of US property, and thus wrote to Timothy Pickering that he thought it sufficient to merely verbally inform Toussaint the States' intention to continue commercial intercourse.[23][28]

Hamilton as slave owner[edit]

| This section may present fringe theories, without giving appropriate weight to the mainstream view, and explaining the responses to the fringe theories. (January 2018) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

Evidence suggests that Hamilton was himself a slave owner.[10][12][13][19][29][1][30][31][32][33][34][35][36][37] Hamilton's grandson, historian Allan McLane Hamilton, agreed with this assessment. As the younger Hamilton wrote in 1910, "It has been stated that Hamilton never owned a negro slave, but this is untrue. We find that in his books there are entries showing that he purchased them for himself and for others."[10][11][1]

In 1784 Hamilton sold a slave named Peggy for £90 to a New York physician named Malachi Treat, whose office was at 18 Little Queen Street.[11][30][36]

According to Hamilton's own expense book, he bought "2 negro servants" for himself from N. Low for $250 in 1796.[38][9][11][1][36] Hamilton's grandson cited this as proof of Hamilton's slave ownership.[1]

Hamilton as slave trader and beneficiary of slavery[edit]

Despite this evidence, not all of Hamilton's biographers feel comfortable declaring definitively that Hamilton owned slaves. Chernow, for example, only goes so far as to say the evidence "suggest[s] that he and Eliza may have owned one or two household slaves".[5]:210[10] Nevertheless, everyone agrees that Hamilton was a beneficiary of slave labour.[11] Chernow notes that his mother owned five adult and four child slaves, and that she "assigned a little boy named Ajax as a house slave to Alexander and another to James."[5][12] Reed reports that these slaves were left to the two Hamilton boys in their mother's will.[13] In 1780, Hamilton married into a wealthy, aristocratic, slaveholding family.[9][10][12] DuRoss points out that those "opposed to slavery might have trouble marrying into a slaveholding family, but it did not appear to bother Hamilton."[9] She claims that Hamilton married Schuyler for status, not love.[9] As a member of this family, Hamilton served as a slave trader,[10][19] a participant in the bartering of slaves,[10][12] who "acted as a financial agent for the sale, lease, or acquisition of slaves for his immediate family."[11] (In addition to conducting transactions on behalf of his in-laws for slave transfer and purchase, he also did this as part of his assignment in the Continental Army.[9]) This activity suggests that any opposition he had to the institution was not absolute,[9] and Magness points out that it shows "a recurring pattern in which Hamilton directly used slaves, conducted slave transactions for his family, and generally benefited from slavery from roughly the date of his marriage in 1780 until the end of his life in 1804."[11] While Chernow suggests that Hamilton may have negotiated these sales reluctantly, Reed questions how Chernow could know this.[10]

In 1784, Hamilton wrote to John Chaloner, a Philadelphia merchant, on behalf of his sister-in-law, Angelica Schuyler Church explaining that she wanted her slave, Ben, returned.[9][11][39]

Since Angelica and her husband, John Barker Church, spent most of their time in Europe, Hamilton also handled the latter's finances.[9] Hamilton deducted $225 from Church's account on 29 May 1797 for the purchase of "a Negro Woman and Child."[9][11][36][40]

Not long after, Hamilton purchased another "Negro Woman" for $90, again, from Church's account.[11][36][40]

In addition to the above examples, there is another example in Hamilton's ledgers that is somewhat more ambiguous, which McDonald chooses to interpret as referring to a paid employee.[5]:239[41]

A main ambition of Hamilton in life was social climbing,[9][36] and since his relationship with the Schuyler family (as well as Washington) made this possible, DuRoss concludes that it was "more important to Hamilton to cultivate these relationships than to make a stand against slavery."[9][36] Although DuRoss believes Hamilton was himself a slave owner, she adds, "It is possible that Hamilton did not own slaves but, even so, his involvement in slave transactions suggests a more ambiguous picture of Hamilton than the 'unwavering abolitionist.'"[9] Similarly, Magness writes, "Hamilton routinely subordinated his antislavery inclinations to other family and political concerns, and he did not ever approach even a modest level of engagement on the issue in his otherwise voluminous published works. To place him nominally in the column of a slave-beneficiary who had qualms with the institution is probably accurate, but to call Alexander Hamilton an abolitionist – let alone the leading abolitionist of his generation – is a historical absurdity."[11]

Summing up Hamilton's complicated involvement with the question of slavery, Professor DuRoss concludes,

Hamilton would have been one of the exceptions to his generation if he had pushed for the abolition of racial slavery. He had supported America's break from Britain, but remained uneasy about riots and revolutions. He favored stability, which was essential for the growth of America. While he maintained ideas about the natural equality of blacks and whites, his actions did not coincide with his ideas. He supported the property rights of slaveholders, which he did to benefit himself or America economically. When he went against individual property rights, it was to secure the reputation of his country or to avoid war, which Hamilton viewed as a hindrance to trade. Besides his beliefs on the right to property and his desire for American prosperity, Hamilton maintained social ambitions. Hamilton chose secure relationships to benefit his station rather than taking a strong stance against slavery. If Hamilton had not secured these relationships, it is doubtful whether he could have accomplished as much as he did. While not a plantation owner, nor an abolitionist, Hamilton attempted to stay on good terms with people who were either one or the other. His goal was to help create a prosperous and powerful America.[23]

See also[edit]

- Alexander Hamilton

- History of slavery in New York

- Slavery in the United States

- Thomas Jefferson and slavery

- George Washington and slavery

References[edit]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Hamilton, Allan McLane (1910). "Friends and Enemies". The Intimate Life of Alexander Hamilton: Based Chiefly Upon Original Family Letters and Other Documents, Many of Which Have Never Been Published. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 268]. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

It has been stated that Hamilton never owned a negro slave, but this is untrue. We find that in his books there are entries showing that he purchased them for himself and for others.

Search this book on

- ↑ Diggins, John Patrick (2007). "The Contemporary Critique of the Enlightenment". In Neil Jumonville; Kevin Mattson. Liberalism for a New Century. p. 35. Search this book on

- ↑ Wilentz, Sean (2010). "Book Reviews". Journal of American History. 97 (2): 476.

- ↑ Chan, Michael D. (2004). "Alexander Hamilton on Slavery". The Review of Politics. 66 (2): 207–31. doi:10.2307/1408953. JSTOR 1408953.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 Chernow, Ron (2004). Alexander Hamilton. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-1-59420-009-0. Search this book on

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Stewart, David O. (2007). "Wilson's bargain: May 31–June 10". The Summer of 1787: The Men Who Invented the Constitution. New York, N. Y.: Simon & Schuster Paperbacks (published 2008). pp. 73, 79–80. ISBN 978-0-7432-8693-0. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

In mid-August, the New Yorkers resolved to petition the Convention for abolition, only to reverse themselves the following day upon "being informed that it was probable that the Convention would not take up the business." That second meeting was attended by Alexander Hamilton, Convention delegate and lifelong opponent of slavery, who presumably advised against pursuing the petition.

Search this book on

- ↑ Braun, Jerome (2011). "Plutocracy and the Labor Movement". To Break Our Chains: Social Cohesiveness and Modern Democracy. Danvers, MA: Koninklijke Brill NV. pp. 330. ISBN 978-90-04-19027-6.

Alexander Hamilton[…]was a leading anti-slavery advocate

Search this book on

- ↑ Marable, Manning (2006). "Living Black History: Black Consciousness, Place, and America's Master Narrative". Living Black History: How Reimagining the African-American Past Can Remake America's Racial Future. Basic Books (published 2011). p. 9. ISBN 978-0-465-04395-8. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

At the same time, there were early prominent alumni of Columbia, such as Alexander Hamilton, who vigorously opposed the slave trade and slavery's expansion.

Search this book on

- ↑ 9.00 9.01 9.02 9.03 9.04 9.05 9.06 9.07 9.08 9.09 9.10 9.11 9.12 9.13 9.14 9.15 9.16 9.17 9.18 9.19 9.20 9.21 9.22 9.23 9.24 9.25 9.26 9.27 9.28 DuRoss, Michelle (2011). "Somewhere in Between: Alexander Hamilton and Slavery". The Early America Review: A Journal of People, Issues, and Events in 18th Century America. Varsity Tutors. 9 (4): 1. Archived from the original on 11 October 2011. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

Alexander Hamilton's biographers praise Hamilton for being an abolitionist, but they have overstated Hamilton's stance on slavery. […] [W]hen the issue of slavery came into conflict with his personal ambitions, his belief in property rights, or his belief of what would promote America's interests, Hamilton chose those goals over opposing slavery. In the instances where Hamilton supported granting freedom to blacks, his primary motive was based more on practical concerns rather than an ideological view of slavery as immoral. […] When Hamilton had to make a choice between his social ambitions and his desire to free slaves, he opted to follow his ambitions. […] Hamilton never mentioned anything in his correspondence about the horrors of plantation slavery in the West Indies. […] If Hamilton hated the slave system in the West Indies, it might have been because he was not a part of it. […] Someone opposed to slavery might have trouble marrying into a slaveholding family, but it did not appear to bother Hamilton. […] Hamilton conducted transactions for the purchase and transfer of slaves[…] Hamilton deducted $225 from Church's account for the purchase of "a Negro Woman and Child." […]it was more important to Hamilton to cultivate these relationships than to make a stand against slavery. […] Hamilton supported giving slaves their freedom if they joined the Continental Army because he believed it was in the best interest of America, not because he wanted to free slaves. […] Hamilton has been accused of owning slaves, by scholars and his grandson, which suggests that any beliefs he has on the quality and natural rights ofs blacks did not always translate into action. […] Hamilton was motivated by practical terms more so than any ideology that espoused the equality of the races. […] [Richard Brookhiser] does not show any direct involvement of Hamilton in the quest for New York anti-slavery laws. The Society's records lack substantial information about Hamilton suggesting that he did not play a dominant role in the society. […] [Hamiton's] attendance at meetings was sporadic. Moreover, the records of the Manumissions Society, along with Hamilton's papers, lack any real discussion from Hamilton regarding his thoughts on the society or what the society should strive to achieve. […] Although the anti-slavery society in Pennsylvania explicitly pushed for the abolition of slavery, the anti-slavery society Hamilton belonged to advocated the manumission of slaves. The Society said that people should free their slaves, not that they should have to free their slaves. […] The New York Evening Post, founded by Hamilton, contained advertisements for goods produced by slaves.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 10.6 10.7 10.8 10.9 Reed, Ishmael (21 August 2015). ""Hamilton: the Musical:Black Actors Dress Up like Slave Traders…and It's Not Halloween". counterpunch.org. Petrolia, CA: CounterPunch. Archived from the original on 26 August 2015. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

Establishment historians write best sellers in which some of the cruel actions of the Founding Fathers are smudged over if not ignored altogether. They're guilty of a cover-up. This is the case with Alexander Hamilton whose life has been scrubbed with a kind of historical Ajax until it sparkles. His reputation has been shored up as an abolitionist and someone who was opposed to slavery. Not true. […] Even Ron Chernow, author of Alexander Hamilton, upon which the musical Hamilton is based, admits (kinda), reluctantly, that Hamilton and his wife may, [his italics], have owned two household slaves and may have negotiated the sale of slaves on behalf of his in-laws, the Schuylers. Chernow says that Hamilton may have negotiated these sales "reluctantly?" How does he know this? […] Like other founding fathers, Hamilton found slavery an "evil," yet was a slave trader. […] Historians, who serve as lackeys for famous, wealthy white men[…] So what's the difference between Ariel Castro who kept three women against their will and Alexander Hamilton and other founding fathers? His groupies argue that despite his flaws—they don't include the slavet—rading parts–he was smart. Well so was Ariel Castro. He was able to evade detection by even members of his family. For years. Moreover did he work these women from sun up to sun down without paying them? Maybe Broadway will do a musical about his life. […] Maybe that's why the establishment critics leave out the slave parts. The idea that Black Lives Matter is an improvement over their slavery status, where blacks were treated as objects to be bought and sold, worked, beaten, killed and fucked. […] Now I have seen everything. Can you imagine Jewish actors in Berlin’s theaters taking roles of Goering? Goebbels? Eichmann? Hitler? […] When I brought up the subject of Hamilton's slaveholding in a Times' comment section, a white man accused me of political correctness. […] The very clever salesman for this project is Lin-Manuel Miranda. He compares Hamilton, a man who engaged in cruel practices against those who had been kidnapped from their ancestral homes, with that of a slave, Tupac Shakur. He is making profits for his investors with glib appeals such as this one.

- ↑ 11.00 11.01 11.02 11.03 11.04 11.05 11.06 11.07 11.08 11.09 11.10 11.11 11.12 11.13 Magness, Phillip W. (23 June 2015). "Alexander Hamilton's exaggerated abolitionism". PhilMagness.com. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 13 October 2016.. Also available as Magness, Phillip W. (27 June 2015). "Alexander Hamilton's exaggerated abolitionism". History News Network. Washington. Archived from the original on 4 April 2016. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

There's a major problem with this narrative though: the evidence of Hamilton's "abolitionism" is vastly overstated, if it even exists at all. […] Hamilton’s relationship with slavery is far from unblemished. […] It is one of many such examples in Hamilton’s papers in which he acted as a financial agent for the sale, lease, or acquisition of slaves for his immediate family. […] While such actions are not atypical for wealthy persons in the late 18th century, they show a recurring pattern in which Hamilton directly used slaves, conducted slave transactions for his family, and generally benefited from slavery from roughly the date of his marriage in 1780 until the end of his life in 1804 […] Keep in mind that Hamilton was a prolific newspaper editorialist, penning hundreds of typically pseudonymous tracts on all manner of political issues of his day. A striking feature of the Hamiltonian corpus is the general absence of any clear, unequivocal exposition of the "abolitionist" viewpoint so many of his biographers have attributed to him. In this respect, he stands in marked contrast to other prominent antislavery men of his era who wrote extensively on the subject. Consider John Adams, who despite compromising on the issue to retain the southern states in the nascent republic, made his moral objections to slavery clearly known. Or compare Hamilton's silence to Benjamin Franklin, a slave-owner in his younger days who converted to the abolitionist cause and became an outspoken antislavery man by the end of his life. One might even look to Thomas Jefferson, owner of a large Virginia plantation who nonetheless wrote multiple works conceding the immorality of the institution and expressing his fears of what its future entailed for the United States. Hamilton, by contrast, seldom even referred to slavery in his writings beyond an abstract generalization and never approached the specificity of many of his contemporaries in engaging the subject. […] Hamilton routinely subordinated his antislavery inclinations to other family and political concerns, and he did not ever approach even a modest level of engagement on the issue in his otherwise voluminous published works. To place him nominally in the column of a slave-beneficiary who had qualms with the institution is probably accurate, but to call Alexander Hamilton an abolitionist – let alone the leading abolitionist of his generation – is a historical absurdity.

- ↑ 12.00 12.01 12.02 12.03 12.04 12.05 12.06 12.07 12.08 12.09 12.10 "On Hamilton and Slavery". Bring On A Rumpus. 15 May 2016. Archived from the original on 15 October 2016. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

First, let's get one thing straight: Hamilton was NOT an abolitionist. I don't care how you look at it, he simply was not. He made deals involving slaves, he married one of the largest slave holding families in New York, and he was obsessed with raising his station in society, which meant, you guessed it, owning/renting slaves.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 Reed, Ishmael (15 April 2016). "Hamilton and the Negro Whisperers: Miranda's Consumer Fraud". counterpunch.org. Petrolia, CA: CounterPunch. Archived from the original on 24 April 2016. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

Hamilton actually owned slaves. […] Hamilton's mother also owned slaves and in her will, left the slaves to Hamilton and his brother. […] Ms. Gordon-Reed further commented that while Hamilton publicly criticized Jefferson's views on the biological inferiority of blacks, his record from the 1790s until his death in 1804 includes little to no action against slavery. […] This latest attempt to whitewash a founding father for money, is preceded by a farce called, "Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson" which lionizes Andrew Jackson, the Eichmann of American extermination policy. […] It's also a disappointment that Miranda persuaded the treasury to keep Hamilton on the ten-dollar bill, a man who held slaves, instead of replacing him with Harriet Tubman, who freed slaves.

- ↑ David Brion Davis, Inhuman Bondage, p. 156;

- ↑ Mitchell, pp. I:175–77, I:550 n. 92, citing the Journals of the Continental Congress, March 29, 1779; Wallace, p. 455.

- ↑ Hamilton to Jay, March 14, 1779; McManus, pp. 154–57.

- ↑ McDonald, p. 34; Flexner, pp. 257–58.

- ↑ McManus, p. 168.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Snell, Colin (1 February 2013). "Hamilton: The Founding Father of Big Government". The College Conservative. N. J. Archived from the original on 14 October 2016. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

While he did own slaves, lets us not forget, though we often do, that Hamilton was also a slave owner. Alexander Hamilton participated in the slave trade in New York City, purchasing them and retaining some that were given as gifts from his in-laws. The New York Aristocrat kept them around for house work, and never proposed any legislation for the curtailment of the practice.

- ↑ Littlefield, p. 126, citing Syrett, pp. 3:605–8.

- ↑ Hamilton, Alexander (26 May 1783). Syrett, Harold C., ed. The Papers of Alexander Hamilton. 3. New York: Columbia University Press (published 1962). p. 365. Search this book on

. Made available online as "Continental Congress Motion of Protest against British Practice of Carrying off American Negroes, [26 May 1783]". archives.gov. Founders Online. Washington, D. C.: National Archives and Records Administration. 26 May 1783. Archived from the original on 12 August 2016. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

. Made available online as "Continental Congress Motion of Protest against British Practice of Carrying off American Negroes, [26 May 1783]". archives.gov. Founders Online. Washington, D. C.: National Archives and Records Administration. 26 May 1783. Archived from the original on 12 August 2016. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- ↑ Hamilton, Alexander (1 June 1783). Syrett, Harold C., ed. The Papers of Alexander Hamilton. 3. New York: Columbia University Press (published 1962). pp. 367–372. Search this book on

. Made available online as "From Alexander Hamilton to George Clinton, 1 June 1783". archives.gov. Founders Online. Washington, D. C.: National Archives and Records Administration. 1 June 1783. Archived from the original on 14 October 2016. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

. Made available online as "From Alexander Hamilton to George Clinton, 1 June 1783". archives.gov. Founders Online. Washington, D. C.: National Archives and Records Administration. 1 June 1783. Archived from the original on 14 October 2016. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 23.4 23.5 23.6 DuRoss, Michelle (2011). "Somewhere in Between: Alexander Hamilton and Slavery [Continued from page 1]". The Early America Review: A Journal of People, Issues, and Events in 18th Century America. Varsity Tutors. 9 (4): 1. Archived from the original on 25 November 2011. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

Hamilton was more comfortable advocating the prevention of re-enslavement rather than abolition of slavery because it did not involve the issue of property rights. Still, regardless of Hamilton's ideals about freedom and slavery, his main objective was securing American power. Hamilton stressed that his position resulted from his concern for "national honor, safety and advantage." […] Hamilton's primary motive for relinquishing his former claim on the British returning former slaves to their owners had more to do with the benefits it would bring to New York than with his concern for freeing slaves. Hamilton wanted to do what was in the interest of the United States; that he had to sacrifice the return of blacks or compensation for slaveholders was a by-product, not his priority. To be sure, his priority was not to uphold slavery either. Hamilton was trying to accommodate the southern slaveholders, but he was also trying to secure what he thought was the best deal for America. […] Hamilton did not give up on the return of or compensation for Negroes carried away by the British because he wanted blacks to be free, he did so because he did not think the issue was important enough to risk war with Britain. […] Hamilton's reaction was not the reaction of an abolitionist wishing to see blacks free. Instead of sympathizing with the black slaves on the island, Hamilton sympathized with their owners. […] Hamilton worried that an uprising like the one in Saint Dominique would occur in the U.S. if the strength of the government was compromised. […] Hamilton would have been one of the exceptions to his generation if he had pushed for the abolition of racial slavery. He had supported America's break from Britain, but remained uneasy about riots and revolutions. […] While he maintained ideas about the natural equality of blacks and whites, his actions did not coincide with his ideas. He supported the property rights of slaveholders, which he did to benefit himself or America economically. When he went against individual property rights, it was to secure the reputation of his country or to avoid war, which Hamilton viewed as a hindrance to trade. Besides his beliefs on the right to property and his desire for American prosperity, Hamilton maintained social ambitions. Hamilton chose secure relationships to benefit his station rather than taking a strong stance against slavery.

- ↑ Horton, p. 22.

- ↑ Horton; Kennedy, pp. 97–8; Littlefield; Wills, pp. 35, 40.

- ↑ Hamilton, Alexander (19 November 1792). Syrett, Harold C., ed. The Papers of Alexander Hamilton. 13. New York: Columbia University Press (published 1967). pp. 169–173. Search this book on

. Made available online as "From Alexander Hamilton to George Washington, 19 November 1792". archives.gov. Founders Online. Washington, D. C.: National Archives and Records Administration. 19 November 1792. Archived from the original on 14 October 2016. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

. Made available online as "From Alexander Hamilton to George Washington, 19 November 1792". archives.gov. Founders Online. Washington, D. C.: National Archives and Records Administration. 19 November 1792. Archived from the original on 14 October 2016. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- ↑ Hamilton, Alexander (21 September 1791). Syrett, Harold C., ed. The Papers of Alexander Hamilton. 9. New York: Columbia University Press (published 1965). p. 220. Search this book on

. Made available online as "From Alexander Hamilton to Jean Baptiste de Ternant, 21 September 1791". archives.gov. Founders Online. Washington, D. C.: National Archives and Records Administration. 21 September 1791. Archived from the original on 14 October 2016. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

. Made available online as "From Alexander Hamilton to Jean Baptiste de Ternant, 21 September 1791". archives.gov. Founders Online. Washington, D. C.: National Archives and Records Administration. 21 September 1791. Archived from the original on 14 October 2016. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Hamilton, Alexander (9 February 1799). Syrett, Harold C., ed. The Papers of Alexander Hamilton. 22. New York: Columbia University Press (published 1975). p. 475. Search this book on

. Made available online as "From Alexander Hamilton to Timothy Pickering, 9 February 1799". archives.gov. Founders Online. Washington, D. C.: National Archives and Records Administration. 9 February 1799. Archived from the original on 14 October 2016. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

. Made available online as "From Alexander Hamilton to Timothy Pickering, 9 February 1799". archives.gov. Founders Online. Washington, D. C.: National Archives and Records Administration. 9 February 1799. Archived from the original on 14 October 2016. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- ↑ DiLorenzo, Thomas (14 July 2008). "Hamiltonian Hagiography". LewRockwell.com. Lew Rockwell. Archived from the original on 10 October 2013. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

Hamilton was a slave owner; he never advocated the abolition of slavery per se; he once purchased six slaves at a slave auction (for his brother-in-law, says biographer Ron Chernow); and he once returned runaway slaves to their owner.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Hamilton, Alexander (1784). Syrett, Harold C., ed. The Papers of Alexander Hamilton. 3. New York: Columbia University Press (published 1962). pp. 6–67. Search this book on

. Made available online as "Cash Book, [1 March 1782–1791]". archives.gov. Founders Online. Washington, D. C.: National Archives and Records Administration. 5 October 2016. Archived from the original on 7 September 2015. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

. Made available online as "Cash Book, [1 March 1782–1791]". archives.gov. Founders Online. Washington, D. C.: National Archives and Records Administration. 5 October 2016. Archived from the original on 7 September 2015. Retrieved 13 October 2016. To a negro wench Peggy sold him

- ↑ Nau, Henry R. (2002). "National Identity: Consequences for Foreign Policy". At Home Abroad: Identity and Power in American Foreign Policy. Ithaca, N. Y.: Cornell University Press. p. 62. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

Jefferson and other founders—George Washington, James Madison, and Alexander Hamilton—owned slaves

Search this book on

- ↑ Matthewson, Tim (2003). "Introduction". A Proslavery Foreign Policy: Haitian–American Relations during the Early Republic. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers. p. 25. ISBN 0-275-98002-2. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

Though Hamilton was a slaveholder, he was a member of the New York Manumission Society

Search this book on

- ↑ Clark, Alan J. (2005). "Introduction". Cipher/Code of Dishonor: Aaron Burr, an American Enigma. Bloomington, IN: Author House. p. xxxii. ISBN 1-4208-4639-6. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

Alexander Hamilton also owned slaves at his death in 1804

Search this book on

- ↑ Sora, Steven (2003). "Master Masons and Their Slaves". Secret Societies of America's Elite: From the Knights Templar to Skull and Bones. Rochester, VT: Destiny Books. p. 216. ISBN 978-1-59477-867-4. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

Like Jefferson, Hamilton owned slaves and called for their freedom; unlike Jefferson, who targeted New York as a city of money-grubbers, Hamilton's lifetime ambition was to found a bank.

Search this book on

- ↑ Stanley, Jack (7 August 2012). "Was Aaron Burr really as bad as we say he was? He was not in any way as corrupt as Hamilton or Jefferson". History in the Raw. Archived from the original on 31 January 2015. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

One has to remember also for a while Hamilton had slaves.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 36.3 36.4 36.5 36.6 silveredbow (2 May 2016). "Did Alexander Hamilton own slaves?". reddit AskHistorians. Archived from the original on 14 October 2016. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

So, did he own slaves? Yes. Was he actually against slavery? Most likely, but he didn't let it get in the way of his domestic comfort or social climbing.

- ↑ Although Jefferson and Hamilton are frequently contrasted, this would place both men in the same camp, viz., slaveholders who nonetheless held reservations about the institution.

- ↑ "1796. Cash to N. Low 2 negro servants purchased by him for me, $250."

- ↑ Hamilton, Alexander (1784). Syrett, Harold C., ed. The Papers of Alexander Hamilton. 3. New York: Columbia University Press (published 1962). pp. 584–585. Search this book on

. Made available online as "From Alexander Hamilton to John Chaloner, [11 November 1784]". archives.gov. Founders Online. Washington, D. C.: National Archives and Records Administration. 11 November 1784. Archived from the original on 14 October 2016. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

. Made available online as "From Alexander Hamilton to John Chaloner, [11 November 1784]". archives.gov. Founders Online. Washington, D. C.: National Archives and Records Administration. 11 November 1784. Archived from the original on 14 October 2016. Retrieved 13 October 2016. Mrs. Renselaaer has requested me to write to you concerning a negro, Ben, formerly belonging to Mrs. Carter who was sold for a term of years to Major Jackson. Mrs. Church has written to her sister that she is very desirous of having him back again; and you are requested if Major Jackson will part with him to purchase his remaining time for Mrs. Church and to send him on to me.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Hamilton, Alexander (1797). Syrett, Harold C., ed. The Papers of Alexander Hamilton. 21. New York: Columbia University Press (published 1974). pp. 109–112. Search this book on

. Made available online as "Account with John Barker Church, [15 June 1797]". archives.gov. Founders Online. Washington, D. C.: National Archives and Records Administration. 29 May 1797. Archived from the original on 14 October 2016. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

. Made available online as "Account with John Barker Church, [15 June 1797]". archives.gov. Founders Online. Washington, D. C.: National Archives and Records Administration. 29 May 1797. Archived from the original on 14 October 2016. Retrieved 13 October 2016. John B. Church Dr. to Cash paid for negro woman & child 225 […] To ditto paid price of Negro Woman 90

- ↑ Specifically, the excerpt that McDonald interprets as referring to the hiring of an employee is, "I expect by Col Hay's return to receive a sufficient sum to pay the value of the woman Mrs. H had of Mrs. Clinton."

Notes[edit]

Further reading[edit]

- James Oliver Horton, "Alexander Hamilton: slavery and race in a revolutionary generation." New-York Journal of American History 65.3 (2004): 16-24. online

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Alexander Hamilton. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Slavery in the United States. |

📰 Article(s) of the same category(ies)[edit]

This article "Alexander Hamilton and slavery" is from Wikipedia. The list of its authors can be seen in its historical and/or the page Edithistory:Alexander Hamilton and slavery. Articles copied from Draft Namespace on Wikipedia could be seen on the Draft Namespace of Wikipedia and not main one.