Ashtiname of Muhammad

| Part of a series on |

| Muhammad |

|---|

|

|

Views |

|

Related |

|

|

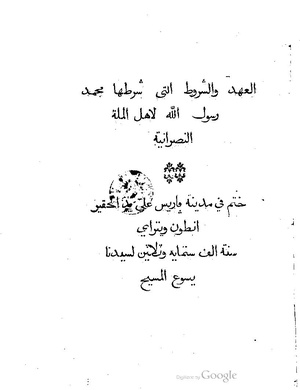

The Ashtiname of Muhammad, also known as the Covenant or Testament (Testamentum) of Muhammad, is a document which is a charter or writ written by Ali[citation needed] and ratified by Muhammad granting protection and other privileges to the followers of Jesus the Nazarene, given to the Christian monks of Saint Catherine's Monastery. It is sealed with an imprint representing Muhammad's hand.[1]

Āshtīnāmeh (IPA: [ɒʃtinɒme]) is a Persian word meaning "Book of Peace", a Persian term for a treaty and covenant.[2]

Document[edit]

English translation of the Ashtiname by Anton F. Haddad[edit]

This is a letter which was issued by Mohammed, Ibn Abdullah, the Messenger, the Prophet, the Faithful, who is sent to all the people as a trust on the part of God to all His creatures, that they may have no plea against God hereafter. Verily God is Omnipotent, the Wise. This letter is directed to the embracers of Islam, as a covenant given to the followers of Jesus the Nazarene in the East and West, the far and near, the Arabs and foreigners, the known and the unknown.

This letter contains the oath given unto them, and he who disobeys that which is therein will be considered a disbeliever and a transgressor to that whereunto he is commanded. He will be regarded as one who has corrupted the oath of God, disbelieved His Testament, rejected His Authority, despised His Religion, and made himself deserving of His Curse, whether he is a Sultan or any other believer of Islam. Whenever Christian monks, devotees and pilgrims gather together, whether in a mountain or valley, or den, or frequented place, or plain, or church, or in houses of worship, verily we are [at the] back of them and shall protect them, and their properties and their morals, by Myself, by My Friends and by My Assistants, for they are of My Subjects and under My Protection.

I shall exempt them from that which may disturb them; of the burdens which are paid by others as an oath of allegiance. They must not give anything of their income but that which pleases them—they must not be offended, or disturbed, or coerced or compelled. Their judges should not be changed or prevented from accomplishing their offices, nor the monks disturbed in exercising their religious order, or the people of seclusion be stopped from dwelling in their cells.

No one is allowed to plunder these Christians, or destroy or spoil any of their churches, or houses of worship, or take any of the things contained within these houses and bring it to the houses of Islam. And he who takes away anything therefrom, will be one who has corrupted the oath of God, and, in truth, disobeyed His Messenger.

Jizya should not be put upon their judges, monks, and those whose occupation is the worship of God; nor is any other thing to be taken from them, whether it be a fine, a tax or any unjust right. Verily I shall keep their compact, wherever they may be, in the sea or on the land, in the East or West, in the North or South, for they are under My Protection and the testament of My Safety, against all things which they abhor.

No taxes or tithes should be received from those who devote themselves to the worship of God in the mountains, or from those who cultivate the Holy Lands. No one has the right to interfere with their affairs, or bring any action against them. Verily this is for aught else and not for them; rather, in the seasons of crops, they should be given a Kadah for each Ardab of wheat (about five bushels and a half) as provision for them, and no one has the right to say to them 'this is too much', or ask them to pay any tax.

As to those who possess properties, the wealthy and merchants, the poll-tax to be taken from them must not exceed twelve drachmas a head per year (i.e. about 200 modern day US dollars).

They shall not be imposed upon by anyone to undertake a journey, or to be forced to go to wars or to carry arms; for the Muslims have to fight for them. Do no dispute or argue with them, but deal according to the verse recorded in the Quran, to wit: ‘Do not dispute or argue with the People of the Book but in that which is best’ [29:46]. Thus they will live favored and protected from everything which may offend them by the Callers to religion (Islam), wherever they may be and in any place they may dwell.

Should any Christian woman be married to a Muslim, such marriage must not take place except after her consent, and she must not be prevented from going to her church for prayer. Their churches must be honored and they must not be withheld from building churches or repairing convents.

They must not be forced to carry arms or stones; but the Muslims must protect them and defend them against others. It is positively incumbent upon every one of the follower of Islam not to contradict or disobey this oath until the Day of Resurrection and the end of the world.[3]

- For other translations of the Ashtiname, including the lists of witnesses, refer to The Covenants of the Prophet Muhammad with the Christians of the World (Angelico Press / Sophia Perennis, 2013) by Dr. John Andrew Morrow.

History[edit]

According to the monks' tradition, Muhammad frequented the monastery and had great relationships and discussions with the Sinai fathers.[4]

Several certified historical copies are displayed in the library of St Catherine, some of which are witnessed by the judges of Islam to affirm historical authenticity. The monks claim that during the Ottoman conquest of Egypt in the Ottoman–Mamluk War (1516–17), the original document was seized from the monastery by Ottoman soldiers and taken to Sultan Selim I's palace in Istanbul for safekeeping.[1][5] A copy was then made to compensate for its loss at the monastery.[1] It also seems that the charter was renewed under the new rulers, as other documents in the archive suggest.[6] Traditions about the tolerance shown towards the monastery were reported in governmental documents issued in Cairo and during the period of Ottoman rule (1517–1798), the Pasha of Egypt annually reaffirmed its protections.[1]

In 1916, Na'um Shuqayr published the Arabic text of the Ashtiname in his Tarikh Sina al-qadim or History of Ancient Sinai. The Arabic text, along with its German translation, was published for a second time in 1918 in Bernhard Moritz's Beiträge zur Geschichte des Sinai-Klosters.

The Testamentum et pactiones inter Mohammedem et Christianae fidei cultores, which was published in Arabic and Latin by Gabriel Sionita in 1630 represents a covenant concluded between Muhammad and the Christians of the World. It is not a copy of the Ashtiname.

The origins of the Ashtiname has been the subject of a number of different traditions, best known through the accounts of European travellers who visited the monastery.[1] These authors include the French knight Greffin Affagart (d. c. 1557), the French traveller Jean de Thévenot (d. 1667) and the English prelate Richard Peacocke,[1] who included an English translation of the text.

Authenticity[edit]

Since the 19th century, several aspects of the Ashtiname, notably the list of witnesses, have been questioned by some scholars.[7] There are similarities to other documents granted to other religious communities in the Near East. One example is Muhammad's alleged letter to the Christians of Najran, which first came to light in 878 in a monastery in Iraq and whose text is preserved in the Chronicle of Seert.[1]

At the beginning of the 20th century, Bernhard Moritz, in his seminal work, concluded from his analysis of the document, that: "The impossibility of finding this document to be authentic is clearly evident. The date, style and content all prove the inauthenticity."[8] Amidu Sanni points out that there are no existent codices, Islamic or otherwise, which predate the 16th century,[9] and Dr Mubasher Hussain has questioned the authenticity of the document on the basis of the fact it contains an impression of a hand which it is claimed belongs to that of Muhammad, but which, rather than showing the inside of the hand as might be expected, "surprisingly shows the outer side of the hand, which is possible only if it is taken using a camera!" Furthermore, he claims that "many language expressions used in this covenant" are dissimilar "to those of the Prophetic expressions preserved in the authentic hadith collections."[10]

The document also uses the term Sultan which would not have been used at the time of Muhammad as the first figure to use this title was the Ghaznavid ruler Mahmud (r. 998 – 1030 CE)[11][12]

The letter also contains a picture of a minaret on the right hand side of the document, however the first minarets were not used until the 9th Century.[13]

Modern influence[edit]

Some have argued that the Ashtiname is a resource for building bridges between Muslims and Christians. For example, in 2009, in the pages of The Washington Post, Muqtedar Khan[14] translated the document in full, arguing that

Those who seek to foster discord among Muslims and Christians focus on issues that divide and emphasize areas of conflict. But when resources such as Muhammad's promise to Christians is invoked and highlighted it builds bridges. It inspires Muslims to rise above communal intolerance and engenders good will in Christians who might be nursing fear of Islam or Muslims.[14]

The Ashtiname is the inspiration for The Covenants Initiative which urges all Muslims to abide by the treaties and covenants that were concluded by Muhammad with the Christian communities of his time.[15]

In 2018, the final legal judgement in the Pakistani Asia Bibi blasphemy case cited the covenant and said that one of Noreen's accusers violated the Ashtiname of Muhammad, a "covenant made by Muhammad with Christians in the seventh century but still valid today".[16] In 2019, Imran Khan, Prime Minister of Pakistan, cited the covenant in a speech delivered at the World Government Summit.[17]

See also[edit]

Other articles of the topic Islam : Nasheed, Family tree of Omar, Umar II, God in Islam, Islamic philosophy, Kaaba, Muhammad Nasiruddin al-Albani

Some use of "" in your query was not closed by a matching "".Some use of "" in your query was not closed by a matching "".

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Ratliff, "The monastery of Saint Catherine at Mount Sinai and the Christian communities of the Caliphate."

- ↑ Dehghani, Mohammad: 'Āshtīnāmeh' va 'Tovāreh', do loghat-e mahjur-e Fārsi dar kuh-e sinā Archived August 11, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. in 'Ayandeh' magazine. 1368 Hš. p. 584.

- ↑ trans. Haddad, Anton F. (1902). "The Oath of the Prophet Mohammed to the Followers of the Nazarene". New York, NY: Board of Counsel, 1902. Retrieved Sep 2, 2018.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-11-13. Retrieved 2013-09-09. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help)CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link) - ↑ Lafontaine-Dosogne, "Le Monastère du Sinaï: creuset de culture chrétiene (Xe-XIIIe siècle)", p. 105.

- ↑ Atiya, "The Monastery of St. Catherine and the Mount Sinai Expedition". p. 578.

- ↑ Ratliff, "The monastery of Saint Catherine at Mount Sinai and the Christian communities of the Caliphate", note 9. Ratliff refers to Mouton, "Les musulmans à Sainte-Catherine au Moyen Âge", p. 177.

- ↑ Moritz, Bernhard. (1918). "Beiträge zur Geschichte des Sinaiklosters im Mittelalter nach arabischen Quellen", p. 11.

- ↑ Sanni. (2015), "The Covenants of the Prophet Muḥammad with the Christians of the World", Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs, DOI: 10.1080/13602004.2015.1112122, p. 2.

- ↑ Mubasher, "John Andrew Morrow. The Covenants of the Prophet Muhammad with the Christians of the World", Islamic Studies, Vol. 57 No. 3-4 (2018), p. 313

- ↑ Esposito, John L., ed. (2003). "Sultan". The Islamic World: Past and Present. Oxford University Press. Search this book on

- ↑ Kramers, J.H.; Bosworth, C.E.; Schumann, O.; Kane, Ousmane (2012). "Sulṭān". In Bearman, P.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C.E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W.P. Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Brill. Search this book on

- ↑ Bloom, Jonathan M. (2013). The minaret. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0748637257. OCLC 856037134. Search this book on

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Khan, Muqtedar (December 30, 2009), "Muhammad's promise to Christians", The Washington Post, archived from the original on January 18, 2010, retrieved 1 December 2012 Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ "covenantsoftheprophet.com". covenantsoftheprophet.com. Retrieved 2018-02-26.

- ↑ Asif Aqeel (31 October 2018). "Pakistan Frees Asia Bibi from Blasphemy Death Sentence". Christianity Today. Retrieved 31 October 2018.

- ↑ Insaf.pk (22 December 2018). "PM Imran Khan Speech at 100 Days Performance of Punjab government" (in اردو). Retrieved 23 December 2018.

Sources[edit]

- Ratliff, Brandie. "The monastery of Saint Catherine at Mount Sinai and the Christian communities of the Caliphate." Sinaiticus. The bulletin of the Saint Catherine Foundation (2008) (archived).

- Haddad, Anton F., trans. The Oath of the Prophet Mohammed to the Followers of the Nazarene. New York: Board of Counsel, 1902; H-Bahai: Lansing, MI: 2004.

- Atiya, Aziz Suryal. "The Monastery of St. Catherine and the Mount Sinai Expedition." Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 96.5 (1952). pp. 578–86.

- Lafontaine-Dosogne, Jacqueline. "Le Monastère du Sinaï: creuset de culture chrétiene (Xe-XIIIe siècle)." In East and West in the Crusader states. Context – Contacts – Confrontations. Acta of the congress held at Hernen Castle in May 1993, ed. Krijnie Ciggaar, Adelbert Davids, Herman Teule. Vol 1. Louvain: Peeters, 1996. pp. 103–129.

Further reading[edit]

Primary sources[edit]

- Arabic Editions of the Achtiname

- Morrow, John Andrew. The Covenants of the Prophet Muhammad with the Christians of the World. Kettering, OH: Angelico Press / Sophia Perennis, 2013.

- Amarah, Muhammad. al-Islam wa al-akhar. Maktabah al-Sharq al-Dawliyyah, 2002.

- Moritz, Bernhard. Beiträge zur Geschichte des Sinai-Klosters im Mittelalter nach arabischen Quellen. Berlin, Verlag der königl. Akademie Der Wissenschaften, 1918. (archive.org)

- Shuqayr, Na‘um. Tarikh Sina al-qadim wa al-hadith was jughrafiyatuha, ma‘a khulasat tarikh Misr wa al-Sham wa al-‘Iraq wa Jazirat al-‘Arab wa ma kana baynaha min al-‘ala’iq al-tijariyyah wa al-harbiyyah wa ghayriha ‘an tariq Sina’ min awwal ‘ahd al-tarikh il al-yawm. [al-Qahirah]: n.p., 1916.

- English, French, and German Translations of the Achtiname

- Thévenot, Jean de. Relation d’un voyage fait au Levant. Paris, L. Billaine, 1665.

- Pococke, Richard. 'Chapter XIV: The Patent of Mahomet, which he granted to the Monks of Mount Sinai; and to Christians in General.' Description of the East. Vol. 1. London, 1743. pp. 268–70.

- Arundale, Francis. Illustrations of Jerusalem and Mount Sinai. London: Henry Colburn, 1837.28–29

- Davenport, John. An Apology for Mohammed and the Koran. London: J. Davy and Sons, 1869. 147–151.

- Naufal, Naufal Effendi. [Translation from Turkish into Arabic completed prior to 1902].

- Moritz, Bernhard. Beiträge zur Geschichte des Sinai-Klosters im Mittelalter nach arabischen Quellen. Berlin, Verlag der königl. Akademie Der Wissenschaften, 1918. (archive.org)

- Affagart, Greffin. Relation de Terre Sainte, ed. J. Chavanon. Paris: V. Lecoffre, 1902. (archive.org)

- Haddad, Anton F., trans. The Oath of the Prophet Mohammed to the Followers of the Nazarene. New York: Board of Counsel, 1902; H-Bahai: Lansing, MI: 2004.

- Skrobucha, Heinz. Sinai. London: Oxford University Press, 1966.58.

- Hobbs, Joseph J. Mount Sinai. Austin: University of Austin Press, 1995. 158–61.

- Morrow, John Andrew. The Covenants of the Prophet Muhammad with the Christians of the World. Tacoma, WA: Angelico Press / Sophia Perennis, 2013.

Secondary sources[edit]

- Atiya, Aziz Suryal (1955). The Arabic Manuscripts of Mount Sinai: A Handlist of the Arabic Manuscripts and Scrolls Microfilmed at the Library of the Monastery of St. Catherine, Mount Sinai. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press. Search this book on

- Atiya, Aziz Suryal. "The Monastery of St. Catherine and the Mount Sinai Expedition." Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 96.5 (1952). pp. 578–86.

- Hobbs, J. (1995). Mount Sinai. Austin: University of Texas Press. pp. 158–61. Search this book on

- Lafontaine-Dosogne, Jacqueline. "Le Monastère du Sinaï: creuset de culture chrétiene (Xe-XIIIe siècle)." In East and West in the Crusader states. Context – Contacts – Confrontations. Acta of the congress held at Hernen Castle in May 1993, ed. Krijnie Ciggaar, Adelbert Davids, Herman Teule. Vol 1. Louvain: Peeters, 1996. pp. 103–129.

- Manaphis, K.A., ed. (1990). Sinai: Treasures of the Monastery of Saint Catherine. Athens. pp. 14, 360–1, 374. Search this book on

- Moritz, B. (1918). "Beitrage zur Geschichte des Sinai-Klosters im Mittelalter nach arabischen Quellen". Abhandlungen der Berliner Akademie.

- Moritz (1928). Abhandlungen der Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. 4: 6–8.CS1 maint: Untitled periodical (link)

- Mouton, Jean-Michel (1998). "Les musulmans à Sainte-Catherine au Moyen Âge". Le Sinai durant l'antiquité et le moyen âge. 4000 ans d'histoire pour un desert. Paris: Editions Errance. pp. 177–82.

- Pelekanidis, S. M.; Christou, P. C.; Tsioumis, Ch.; Kadas, S. N. (1974–1975). The Treasures of Mount Athos [Series A]: Illuminated manuscripts. Athens. Search this book on

A copy in the Simonopetra monastery, p. 546.

A copy in the Simonopetra monastery, p. 546. - Ratliff, Brandie. "The monastery of Saint Catherine at Mount Sinai and the Christian communities of the Caliphate." Sinaiticus. The bulletin of the Saint Catherine Foundation (2008) (archived).

- Sotiriou, G. and M. (1956–58). Icones du Mont Sinaï. 2 vols (plates and texts). Collection de L'Institut francais d'Athènes 100 and 102. Athens. pp. 227–8. Search this book on

- Vryonis, S. (1981). "The History of the Greek Patriarchate of Jerusalem as Reflected in Codex Patriarchus No. 428, 1517–1805". Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies. 7: 29–53. doi:10.1179/030701381806931532.

External links[edit]

- A complete and accurate translation of the charter can be read here [1]

- An English translation of part of the charter can be read here or here.

- Downloadable PDF of the 1630 Arabic and Latin edition at Google Books.

- English translation at Islamic Voice. Archived 2005-11-24 at the Wayback Machine

- Ashtiname of Muhammad (Persian)

- Ashtiname of Muhammad (Urdu)