List of superfoods

This list of superfoods includes any so-called 'superfood' claimed by marketers to have unusually high nutritional or dietary medicinal value, along with known claims and refutations regarding their efficacy. It is important to note that the term is discouraged by professional dieticians and there is no agreed scientific definition, though some attempts have been made to establish limited, relative metrics such as nutrient density.[1]

Algae[edit]

Aphanizomenon flos-aquae[edit]

Aphanizomenon flos-aquae is a blue algae that is a dense source of vitamins, minerals, and other nutrients.[medical citation needed]

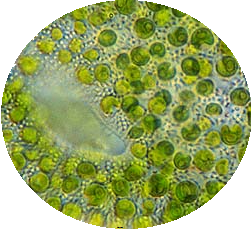

Chlorella[edit]

Chlorella is a genus of single-cell green algae, belonging to the phylum Chlorophyta. It is spherical in shape, about 2 to 10 μm in diameter, and is without flagella. Chlorella contains the green photosynthetic pigments chlorophyll-a and -b in its chloroplast. Through photosynthesis, it multiplies rapidly, requiring only carbon dioxide, water, sunlight, and a small amount of minerals to reproduce.

Chlorella has a number of purported health effects,[2] including an ability to treat cancer.[3] However, according to the American Cancer Society, "available scientific studies do not support its effectiveness for preventing or treating cancer or any other disease in humans".[3]

A 2001 study concluded that "daily dietary supplementation with chlorella may reduce high blood pressure, lower serum cholesterol levels, accelerate wound healing, and enhance immune functions" and recommended further study.[4] A 2002 study concluded that "for some subjects with mild to moderate hypertension, a daily dietary supplement of Chlorella reduced or kept stable their SiDBP".[5]

Spirulina[edit]

Dried Spirulina contains about 60% (51–71%) protein. It is a complete protein containing all essential amino acids, though with reduced amounts of methionine, cysteine and lysine when compared to the proteins of meat, eggs and milk. It is, however, superior to typical plant proteins, such as that from legumes.[6][7]

The U.S. National Library of Medicine reports that Spirulina is no better than milk or meat as a protein source, and was approximately 30 times more expensive per gram.[8]

Spirulina's lipid content is about 7% by weight,[9] and is rich in gamma-linolenic acid (GLA), and also provides alpha-linolenic acid (ALA), linoleic acid (LA), stearidonic acid (SDA), eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and arachidonic acid (AA).[7][10] Spirulina contains vitamins B1 (thiamine), B2 (riboflavin), B3 (nicotinamide), B6 (pyridoxine), B9 (folic acid), vitamin C, vitamin A and vitamin E.[7][10] It is also a source of potassium, calcium, chromium, copper, iron, magnesium, manganese, phosphorus, selenium, sodium and zinc.[7][10] Spirulina contains many pigments which may be beneficial and bioavailable, including beta-carotene, zeaxanthin, chlorophyll-a, xanthophyll, echinenone, myxoxanthophyll, canthaxanthin, diatoxanthin, 3'-hydroxyechinenone, beta-cryptoxanthin and oscillaxanthin, plus the phycobiliproteins c-phycocyanin and allophycocyanin.[11]

Although spirulina contains pseudovitamin B12, it is not bioavailable and the American Dietetic Association and Dietitians of Canada in their position paper on vegetarian diets state that spirulina cannot be counted on as a reliable source of active vitamin B12.[12] The medical literature similarly advises that spirulina is unsuitable as a source of B12.[13][14]

According to the U.S. National Institutes of Health, at present there is insufficient scientific evidence to recommend spirulina supplementation for any human condition, and more research is needed to clarify its benefits, if any.[15]

Wakame (Sea mustard)[edit]

Wakame (ワカメ) is a sea vegetable, or edible seaweed. It has a subtly sweet flavour and is most often served in soups and salads. In English, it can be called "sea mustard". It is traditionally consumed in East Asia including China, Japan, and Korea.

Drinks[edit]

Kombucha[edit]

Kombucha is a lightly effervescent fermented drink of sweetened black tea that is used as a functional food. Although kombucha is claimed to have several beneficial effects on health, these claims are not supported by scientific evidence.

In a recent study, alternative diets such as probiotics, green tea extract and Kombucha tea were fed to broiler chickens to measure the effects of growth and immunity. The chickens fed with Kombucha showed an increase in protein digestibility. The conclusion of the study stated, "adding Kombucha tea (20 % concentration) to wet wheat-based diets improved broiler performance and had a growth-promoting effect. Probiotic diets also resulted in enhanced growth and performance, but to a lesser extent."[16]

Drinking kombucha has been linked to serious side effects and deaths.[3] Reports of adverse reactions may be related to unsanitary fermentation conditions, leaching of compounds from the fermentation vessels, or "sickly" kombucha cultures that cannot acidify the brew.[17]

According to the American Cancer Society, Kombucha has been promoted as a "cure-all" for many conditions, but

| “ | Available scientific evidence does not support claims that Kombucha tea promotes good health, prevents any ailments, or ... works to treat cancer or any other disease. Serious side effects and occasional deaths have been linked with drinking Kombucha tea.[3] | ” |

Wheatgrass[edit]

Wheatgrass is a food prepared from the cotyledons of the common wheat plant, Triticum aestivum (subspecies of the family Poaceae). It is sold either as a juice or powder concentrate. Wheatgrass differs from wheat malt in that it is served freeze-dried or fresh, while wheat malt is convectively dried. Wheatgrass is allowed to grow longer than malt. Like most plants, it contains chlorophyll, amino acids, minerals, vitamins and enzymes.

Proponents of wheatgrass make many claims for its health properties, ranging from promotion of general well-being to cancer prevention. However, according to the American Cancer Society, "available scientific evidence does not support the idea that wheatgrass or the wheatgrass diet can cure or prevent disease".[18] There is some limited evidence of beneficial pharmacological effects from chlorophyll, though this does not necessarily apply to dietary chlorophyll.[19][20]

A small 2002 study showed some evidence that wheatgrass might help with the symptoms of ulcerative colitis, but without further work the significance of this work cannot be determined.[21] Another small 2002 study suggested wheatgrass might help with the side-effects of breast cancer chemotherapy.[22]

Fruits[edit]

Berries[edit]

Possibly the most studied superfood group, berries remain under scientific evaluation and are not proven to have "superfood" health benefits.[23]

Blueberries[edit]

Blueberries, a popular example of a superfood, are not especially nutritious, having high content of only three essential nutrients: vitamin C, vitamin K and manganese.[24]

In a peer-reviewed study of the nutrient density of 41 "powerhouse" fruits and vegetables by the US Center for Disease Control, it was one of six originally intended for study but that failed to qualify entirely.[1]

Strawberries[edit]

Strawberries are a popular example of a superfruit and ranks number two among the top ten fruits in antioxident capacity.

Cape gooseberry (inca berry)[edit]

Physalis peruviana is indigenous to South America but broadly cultivated worldwide. It is closely related to the tomatillo, also a member of the genus Physalis. As a member of the plant family Solanaceae, it is more distantly related to a large number of edible plants, including tomato, eggplant, potato and other members of the nightshades.[25] They are marketed in the United States as Pichuberry™, named after Machu Picchu in order to associate the fruit with its supposed origin in Peru and address the fact that this fruit is actually not a gooseberry as the name 'Cape gooseberry' may imply.[26][27]

According to analyses by the USDA, a 100 g serving of Cape gooseberries is low in calories and contains modest levels of vitamin A, vitamin C, vitamin B1 and vitamin B3, while other nutrients are at low levels.[28]

Basic research on the cape gooseberry showed that its constituents included polyphenols and/or carotenoids.[29][30][31]

Goji berry (wolfberry)[edit]

Goji berries are small red berries, smaller than an average sultana, that are generally dried and then rehydrated to be traditionally consumed in teas, soups, sauces and alcohols of China and Japan. They are known to be exceptionally high in antioxidants, and studies have shown consumption "increases plasma zeaxanthin and antioxidant levels" which suggests a general health benefit with particular respect to reducing vision degradation due to aging.[32]

Camucamu[edit]

A small tropical fruit (Myrciaria dubia) shaped like a cherry that contains high vitamin[33] C content, flavonoids and anthocyanins.[34] A 2008 study suggested that it "may have powerful anti-oxidative and anti-inflammatory properties, compared to vitamin C tablets containing equivalent vitamin C content. These effects may be due to the existence of unknown anti-oxidant substances besides vitamin C or unknown substances modulating in vivo vitamin C kinetics in camu-camu."[35] A 2013 study on rats suggested that it may assist with controlling obesity.[34]

Coconuts[edit]

In recent years, coconut water has been marketed[36] as a natural energy or sports drink due to its high potassium and mineral content. Marketers have also promoted coconut water for having low levels of fat, carbohydrates, and calories. However, marketing claims attributing tremendous health benefits to coconut water are largely unfounded.[37]

Lúcuma[edit]

Pouteria lucuma (one of two species sometimes known as "eggfruit") is a subtropical fruit native to the Andean valleys of Peru. It has high levels of carotene, vitamin B3, and other B vitamins.[citation needed] The round or ovoid fruits are green, with a bright yellow flesh that is often fibrous.

Vegetables[edit]

Cruciferous greens[edit]

Cruciferous vegetables are vegetables of the family Brassicaceae (also called Cruciferae). These vegetables are widely cultivated, with many genera, species, and cultivars being raised for food production such as cauliflower, cabbage, watercress, bok choy, broccoli and similar green leaf vegetables. The family takes its alternate name (Cruciferae, New Latin for "cross-bearing") from the shape of their flowers, whose four petals resemble a cross.

Ten of the most common cruciferous vegetables eaten by people, known colloquially as cole crops,[38] are in a single species (B. oleracea); they are not distinguished from one another taxonomically, only by horticultural category of cultivar groups. Numerous other genera and species in the family are also edible. Cruciferous vegetables are one of the dominant food crops worldwide. They are high in vitamin C and soluble fiber and contain multiple nutrients and phytochemicals.

Greens are ranked highly for nutrient density among "powerhouse" fruits and vegetables in a peer-reviewed US Center for Disease Control study.[1]

Watercress[edit]

Watercress (Nasturtium officinale) is a rapidly growing, aquatic or semi-aquatic, perennial plant native to Europe and Asia, and one of the oldest known leaf vegetables consumed by humans. It is currently a member of the family Brassicaceae, botanically related to garden cress, mustard and radish — all noteworthy for their peppery, tangy, zesty, piquant flavor.

Watercress contains significant amounts of iron, calcium, iodine, and folic acid, in addition to vitamins A and C.[39] Because it is relatively rich in Vitamin C, watercress was suggested (among other plants) by English military surgeon John Woodall (1570–1643) as a remedy for scurvy.

It was ranked first for nutrient density out of 41 "powerhouse" fruits and vegetables in a US Center for Disease Control study.[1]

Dandelion leaves[edit]

Taraxacum /təˈræksək[invalid input: 'ʉ']m/ is a large genus of flowering plants in the family Asteraceae. They are native to Eurasia and North and South America, and two species, T. officinale and T. erythrospermum, are found as weeds worldwide.[40] Both species are edible in their entirety.[41]

Dandelion leaves contain abundant vitamins and minerals, especially vitamins A, C and K, and are good sources of calcium, potassium, iron and manganese.[42]

Historically, dandelion was prized for a variety of medicinal properties, and it contains a wide number of pharmacologically active compounds.[43] Dandelion is used as a herbal remedy in Europe, North America and China.[43] It has been used in herbal medicine to treat infections, bile and liver problems,[43] and as a diuretic.[43]

Preserves[edit]

Sauerkraut[edit]

Sauerkraut ("sour cabbage") is finely cut cabbage that has been fermented by various lactic acid bacteria, including Leuconostoc, Lactobacillus, and Pediococcus.[44][45] It has a long shelf-life and a distinctive sour flavor, both of which result from the lactic acid that forms when the bacteria ferment the sugars in the cabbage. Sauerkraut is also used as a condiment upon various foods, such as meat dishes and hot dogs.[46][47][48][49] Nutritionally, it is a source of vitamins C, B, and K;[50] the fermentation process increases the bioavailability of nutrients rendering sauerkraut even more nutritious than the original cabbage.[51] It is also low in calories and high in calcium and magnesium, and it is a very good source of dietary fiber, folate, iron, potassium, copper and manganese.[50]

The October 23, 2002 issue of the Journal of Agriculture and Food Chemistry reported that Finnish researchers found the isothiocyanates produced in sauerkraut fermentation inhibit the growth of cancer cells in test tube and animal studies.[52] A Polish study in 2010 concluded that "... induction of the key detoxifying enzymes by cabbage juices, particularly sauerkraut, may be responsible for their chemopreventive activity demonstrated by epidemiological studies and in animal models".[53][54][55][56][57][58][59][60]

Sauerkraut is high in the antioxidants lutein and zeaxanthin, both associated with preserving ocular health.[61]

Legumes[edit]

Maca[edit]

Lepidium meyenii is an herbaceous biennial plant of the crucifer family native to the high Andes of Peru around Lake Junin.[62] It is grown for its fleshy hypocotyl (a fused hypocotyl and taproot), which is used as a root vegetable, a medicinal herb, and a supposed aphrodisiac. However, there is no evidence that it benefits sexual or erectile dysfunction in older people,[63] and overall any evidence of aphrodisiac properties is limited.[64]

Raw cocoa[edit]

In general chocolate and cocoa, made from the species Theobroma cacao, are considered to be a rich source of antioxidants such as procyanidins and flavanoids, which may impart anti aging properties.[65][66] Chocolate and cocoa also contain a high level of flavonoids, specifically epicatechin, which may have beneficial cardiovascular effects on health.[67][68][69]

The stimulant activity of cocoa comes from the compound theobromine which is less diuretic as compared to theophylline found in tea.[65] Prolonged intake of flavanol-rich cocoa has been linked to cardiovascular health benefits,[67][68][70] though it should be noted that this refers to raw cocoa and to a lesser extent, dark chocolate, since flavonoids degrade during cooking and alkalizing processes.[71] Studies have found short term benefits in LDL cholesterol levels from dark chocolate consumption.[citation needed] The addition of whole milk to milk chocolate reduces the overall cocoa content per ounce while increasing saturated fat levels.[citation needed] Although one study[72] has concluded that milk impairs the absorption of polyphenolic flavonoids, e.g. epicatechin, a followup[73] failed to find the effect.

Hollenberg and colleagues of Harvard Medical School studied the effects of cocoa and flavanols on Panama's Kuna people, who are heavy consumers of cocoa. The researchers found that the Kuna Indians living on the islands had significantly lower rates of heart disease and cancer compared to those on the mainland who do not drink cocoa as on the islands. It is believed that the improved blood flow after consumption of flavanol-rich cocoa may help to achieve health benefits in hearts and other organs. In particular, the benefits may extend to the brain and have important implications for learning and memory.[74][75][76]

Foods rich in cocoa are alleged to reduce blood pressure, for example according to an analysis of previously published research in the April 9, 2007 issue of Archives of Internal Medicine,[67] one of the JAMA/Archives journals.[77] In one study, raw cocoa had positive effects on blood pressure and markers of heart health,[78] while other research indicated less certainty about the possible effects of cocoa on cardiovascular disease.[79]

A 15-year study of elderly men[80] published in the Archives of Internal Medicine in 2006 found a 50 percent reduction in cardiovascular mortality and a 47 percent reduction in all-cause mortality for the men regularly consuming the most cocoa, compared to those consuming the least cocoa from all sources.

Sacha inchi (inca/sacha/mountain peanut)[edit]

Plukenetia volubilis is a perennial plant with somewhat hairy leaves, in the Euphorbiaceae. It is endemic to the Amazon Rainforest in Peru, where it has been cultivated by indigenous people for centuries. In tropical locations it is often a vine requiring support and producing seeds nearly year-round.

The fruits are capsules of 3 to 5 cm in diameter with 4 to 7 points, are green and ripen blackish brown. On ripening the fruits contain a soft black wet pulp that is messy and inedible, so are normally left to dry on the plant before harvest. By two years of age, often up to a hundred dried fruits can be harvested at a time, giving 400 to 500 seeds a few times a year. Fruit capsules usually consist of four to five lobes, but some may have up to seven.

Raw seeds are inedible, but roasting after shelling makes them very palatable. The seeds have high protein (27%) and oil (35–60%) content, and the oil is rich in the essential fatty acids omega-3 linolenic acid (≈45–53% of total fat content) and omega-6 linoleic acid (≈34–39% of fat content), as well as non-essential omega-9 (≈6–10% of fat content).[81] They are also rich in iodine,[citation needed] vitamin A,[citation needed] and vitamin E.

Fatty fish[edit]

Mackerel, salmon and sardines[citation needed]

Mushrooms[edit]

Chaga mushrooms [82]

Oyster mushrooms

Cordyceps

Maitake mushrooms [83]

Certain wild mushrooms[citation needed]

Seeds[edit]

Chia seeds[edit]

Salvia hispanica is a species of flowering plant in the mint family, Lamiaceae, native to central and southern Mexico and Guatemala.[84] The 16th-century Codex Mendoza provides evidence that it was cultivated by the Aztec in pre-Columbian times; economic historians have suggested it was as important as maize as a food crop.[85] It is still used in Paraguay, Bolivia, Argentina, Mexico and Guatemala, sometimes with the seeds ground or with whole seeds used for nutritious drinks and as a food source.[86][87]

Chia is grown commercially for its seed, a food that is rich in omega-3 fatty acids, since the seeds yield 25–30% extractable oil, including α-linolenic acid (ALA). Of total fat, the composition of the oil can be 55% ω-3, 18% ω-6, 6% ω-9, and 10% saturated fat.[88]

According to the USDA, a one ounce (28 gram) serving of chia seeds contains 9 grams of fat, 5 milligrams of sodium, 11 grams of dietary fiber, 4 grams of protein, 18% of the recommended daily intake of calcium, 27% phosphorus and 30% manganese.[88] These nutrient values are similar to other edible seeds, such as flax or sesame.[89][90]

In 2009, the European Union approved chia seeds as a novel food, allowing up to 5% of a bread product's total matter.[91]

Chia seeds may be added to other foods as a topping or put into smoothies, breakfast cereals, energy bars, yogurt, made into a gelatin-like substance, or consumed raw.[92][93]

Although preliminary research indicates potential for health benefits from consuming chia seeds, this work remains sparse and inconclusive.[94]

One pilot study found that 10 weeks ingestion of 25 grams per day of milled chia seeds, compared to intact seeds, produced higher blood levels of alpha-linolenic acid and eicosapentaenoic acid, an omega-3 long-chain fatty acid considered good for the heart, while having no effect on inflammation or disease risk factors.[95][96]

Flax seeds[edit]

Flax seeds contain high levels of dietary fiber as well as lignans, an abundance of micronutrients and omega-3 fatty acids. Studies have shown that flax seeds may lower cholesterol levels, although with differing results in terms of gender. One study found results were better for women[97] whereas a later study found benefits only for men.[98] Initial studies suggest that flax seeds taken in the diet may benefit individuals with certain types of breast[99][100] and prostate cancers.[101] A study done at Duke University suggests that flaxseed may stunt the growth of prostate tumors,[101] although a meta-analysis found the evidence on this point to be inconclusive.[102] Flax may also lessen the severity of diabetes by stabilizing blood-sugar levels.[103] There is some support for the use of flax seed as a laxative due to its dietary fiber content[104] though excessive consumption without liquid can result in intestinal blockage.[105]

Linum usitatissimum seeds have been used in the traditional Austrian medicine internally (directly soaked or as tea) and externally (as compresses or oil extracts) for treatment of disorders of the respiratory tract, eyes, infections, cold, flu, fever, rheumatism and gout.[106]

One of the main components of flax is lignan, which has plant estrogen as well as antioxidants (flax contains 75-800 times more lignans than other plant foods contain).[107]

Hemp seeds[edit]

Hemp seeds have been used for millennia in China, where they are known as 麻子 (pinyin: mazi) and reference was first made to their gathering prior to winter "in the ninth month"[108] in the Classic of Poetry (which is dated to the 11th to 7th centuries BC). They can be eaten raw, ground into a meal, sprouted, made into hemp milk (akin to soy milk), prepared as tea,[109] and used in baking. Approximately 44% of the weight of hempseed is edible oils, containing about 80% essential fatty acids (EFAs); e.g., linoleic acid, omega-6 (LA, 55%), alpha-linolenic acid, omega-3 (ALA, 22%), in addition to gamma-linolenic acid, omega-6 (GLA, 1–4%) and stearidonic acid, omega-3 (SDA, 0–2%). Proteins (including edestin) are the other major component (33%). Hempseed's amino acid profile is "complete" when compared to more common sources of proteins such as meat, milk, eggs and soy.[110] Hemp protein contains all nutritionally significant amino acids, including the 9 essential ones[111] adult bodies cannot produce. Proteins are considered complete when they contain all the essential amino acids in sufficient quantities and ratios to meet the body's needs. The proportions of linoleic acid and alpha-linolenic acid in one tablespoon (15 ml) per day of hemp oil easily provides human daily requirements for EFAs.[citation needed]

Whole grains[edit]

Amaranth[edit]

Amaranthus is a cosmopolitan genus of annual or short-lived perennial plants. Some amaranth species are cultivated as leaf vegetables, cereals, and ornamental plants. Most of the species from Amaranthus are summer annual weeds and are commonly referred to as pigweed.[112]

Amaranth seeds contain lysine, an essential amino acid, limited in other grains or plant sources.[113][unreliable source?] Most fruits and vegetables do not contain a complete set of amino acids, and thus different sources of protein must be used. Amaranth too is limited in some essential amino acids, such as leucine and threonine.[114][115] Amaranth seeds are therefore a promising complement to common grains such as wheat germ, oats, and corn because these common grains are abundant sources of essential amino acids found to be limited in amaranth.[116][117]

Amaranth may be a promising source of protein to those who are gluten sensitive, because unlike the protein found in grains such as wheat and rye, its protein does not contain gluten.[118] According to a 2007 report, amaranth compares well in nutrient content with gluten-free vegetarian options such as buckwheat, corn, millet, wild rice, oats and quinoa.[119][120]

Several studies have shown that like oats, amaranth seed or oil may be of benefit for those with hypertension and cardiovascular disease; regular consumption reduces blood pressure and cholesterol levels, while improving antioxidant status and some immune parameters.[121][122][123] While the active ingredient in oats appears to be water-soluble fiber, amaranth appears to lower cholesterol via its content of plant stanols and squalene.

Amaranth remains an active area of scientific research for both human nutritional needs and foraging applications. Over 100 scientific studies suggest a somewhat conflicting picture on possible anti-nutritional and toxic factors in amaranth, more so in some particular strains of amaranth. Lehmann, in a review article, identifies some of these reported anti-nutritional factors in amaranth to be phenolics, saponins, tannins, phytic acid, oxalates, protease inhibitors, nitrates, polyphenols and phytohemagglutinins.[124] Of these, oxalates and nitrates are of more concern when amaranth grain is used in foraging applications. Some studies suggest thermal processing of amaranth, particularly in moist environment, prior to its preparation in food and human consumption may be a promising way to reduce the adverse effects of amaranth's anti-nutritional and toxic factors.

Quinoa[edit]

Quinoa is a species of goosefoot (Chenopodium), is a grain crop grown primarily for its edible seeds. It is a pseudocereal rather than a true cereal, as it is not a member of the true grass family. As a chenopod, quinoa is closely related to species such as beetroots, spinach and tumbleweeds. It is high in protein, lacks gluten, and is tolerant of dry soil.

Protein content is very high for a cereal/pseudo-cereal (14% by mass), but not as high as most beans and legumes. The protein content per 100 calories is higher than brown rice, potatoes, barley and millet, but is less than wild rice and oats.[125] Nutritional evaluations indicate that quinoa is a source of complete protein.[126][127][128] Other sources claim its protein is not complete but relatively high in essential amino acids.[129] The grain is a good source of dietary fiber and phosphorus and is high in magnesium and iron. It is a source of calcium, and thus is useful for vegans and those who are lactose intolerant.[130] It is gluten-free and considered easy to digest. Because of these characteristics, it is being considered a possible crop in NASA's Controlled Ecological Life Support System for long-duration human occupied space flights.[131]

The grain may be germinated in its raw form to boost its nutritional value, provided that the grains are rinsed thoroughly to remove any saponin.[132] It has a notably short germination period: only 2–4 hours in a glass of clean water is enough to make it sprout and release gases, as opposed to 12 hours with wheat.[133] This process, besides its nutritional enhancements, softens the seeds, making them suitable to be added to salads and other cold foods.

Other pseudo grains derived from seeds are similar in complete protein levels; buckwheat is 18% protein compared to 14% for Quinoa; Amaranth, a related species to Quinoa, ranges from 12 to 17.5%

Leaves[edit]

Moringa oleifera (drumstick/horseradish/ben oil/benzoil tree)[edit]

The leaves, eaten in Cambodia, the Philippines, South India, Sri Lanka and Africa, are the most nutritious part of the plant, being a significant source of B vitamins, vitamin C, provitamin A as beta-carotene, vitamin K, manganese and protein, among other essential nutrients.[134][135] When compared with common foods particularly high in certain nutrients by weight, cooked moringa leaves are considerable sources of these same nutrients.

Some of the calcium in moringa leaves is bound as crystals of calcium oxalate[136] though at levels 25-45 times less than that found in spinach, which is a negligible amount.

The leaves are cooked and used like spinach. In addition to being used fresh as a substitute for spinach, its leaves are commonly dried and crushed into a powder used in soups and sauces. As with most foods, heating moringa above 60 °C destroys some of the nutritional value.

Other parts of the plant are also edible, including immature seed pods ("drumsticks"), mature seeds, oil pressed from the mature seeds, and the roots.

See also[edit]

Other articles of the topic Food : Kreplach, Honey, Starbucks Corporation

Some use of "" in your query was not closed by a matching "".Some use of "" in your query was not closed by a matching "".

References[edit]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 di Noia, Jennifer (2014-06-05). "Defining Powerhouse Fruits and Vegetables: A Nutrient Density Approach". Preventing Chronic Disease. National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (USA). 11. doi:10.5888/pcd11.130390. ISSN 1545-1151. Retrieved 2014-06-11.

- ↑ Super User. "Sun Chlorella, Going Green from the Inside Out". lasentinel.net.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 "Chlorella". American Cancer Society. 29 April 2011. Retrieved 13 September 2013. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "acs" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 11347287, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=11347287instead. - ↑ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 12495586, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=12495586instead. - ↑ Ciferri O (December 1983). "Spirulina, the edible microorganism". Microbiol. Rev. 47 (4): 551–78. PMC 283708. PMID 6420655.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Babadzhanov A.S.; et al. (2004). "Chemical Composition of Spirulina Platensis Cultivated in Uzbekistan". Chemistry of Natural Compounds. 40 (3): 276–279. doi:10.1023/b:conc.0000039141.98247.e8.

- ↑ "Blue-green algae". MedlinePlus. U.S. National Library of Medicine. November 18, 2010. Retrieved April 15, 2011.

- ↑ Kachroo, Deepa; Jolly, Shaneen M. Singh; Ramamurthy, Viraraghavan (2006). "Modulation of unsaturated fatty acids content in algae Spirulina platensis and Chlorella minutissima in response to herbicide SAN 9785". Electronic Journal of Biotechnology. 9 (4): 0. doi:10.2225/vol9-issue4-fulltext-5.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Tokusoglu O., Unal M.K.; Uunal (2003). "Biomass Nutrient Profiles of Three Microalgae: Spirulina platensis, Chlorella vulgaris, and Isochrisis galbana". Journal of Food Science. 68 (4): 2003. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2621.2003.tb09615.x.

- ↑ Vonshak, A. (ed.). Spirulina platensis (Arthrospira): Physiology, Cell-biology and Biotechnology. London: Taylor & Francis, 1997.

- ↑ Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics and Dietitians of Canada: Vegetarian diets

- ↑ Watanabe F (2007). "Vitamin B12 sources and bioavailability". Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood). 232 (10): 1266–74. doi:10.3181/0703-MR-67. PMID 17959839.

Most of the edible blue-green algae (cyanobacteria) used for human supplements predominantly contain pseudovitamin B(12), which is inactive in humans. The edible cyanobacteria are not suitable for use as vitamin B(12) sources, especially in vegans.

- ↑ Watanabe F, Katsura H, Takenaka S, Fujita T, Abe K, Tamura Y, Nakatsuka T, Nakano Y; Katsura; Takenaka; Fujita; Abe; Tamura; Nakatsuka; Nakano (1999). "Pseudovitamin B(12) is the predominant cobamide of an algal health food, spirulina tablets". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 47 (11): 4736–41. doi:10.1021/jf990541b. PMID 10552882.

The results presented here strongly suggest that spirulina tablet algal health food is not suitable for use as a B12 source, especially in vegetarians.

CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ "Blue-green algae". MedlinePlus. National Institutes of Health. July 6, 2011. Retrieved October 4, 2011.

- ↑ Afsharmanesh, M., and B. Sadaghi. "Effects of Dietary Alternatives (probiotic, Green Tea Powder, and Kombucha Tea) as Antimicrobial Growth Promoters on Growth, Ileal Nutrient Digestibility, Blood Parameters, and Immune Response of Broiler Chickens." Comparative Clinical Pathology (2013): n. pag. Springer Journals. Web. 13 Apr. 2014.

- ↑ Phan, TG; Estell, J; Duggin, G; Beer, I; Smith, D; Ferson, MJ (1998). "Lead poisoning from drinking Kombucha tea brewed in a ceramic pot". The Medical journal of Australia. 169 (11–12): 644–6. PMID 9887919.

- ↑ "Wheatgrass". American Cancer Society. November 2008. Retrieved August 2013. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - ↑ de Vogel, Johan; Denise S. M. L. Jonker-Termont, Martijn B. Katan,and Roelof van der Meer (August 2005). "Natural Chlorophyll but Not Chlorophyllin Prevents Heme-Induced Cytotoxic and Hyperproliferative Effects in Rat Colon". J. Nutr. The American Society for Nutritional Sciences. 135 (8): 1995–2000. PMID 16046728.CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link)

- ↑ Ferruzzia, Mario G.; Blakesleeb, Joshua (January 2007). "Digestion, absorption, and cancer preventative activity of dietary chlorophyll derivatives". Nutrition Research. 27 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1016/j.nutres.2006.12.003.

- ↑ "Wheat grass | Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center". Mskcc.org. Retrieved 2013-04-19.

- ↑ "What is wheatgrass?". WebMD. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ↑ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 18211023, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=18211023instead. - ↑ "In-depth nutrient profile for blueberries". World's Healthiest Foods. 2014. Retrieved 3 April 2014.

- ↑ Morton JF (1987). "Cape gooseberry, Physalis peruviana L. in Fruits of Warm Climates". Purdue University, Center for New Crops & Plant Products.

- ↑ Galarza, Daniella. "This Goose(berry) is Cooked: Let's Talk About the Pichuberry". Los Angeles Magazine. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- ↑ Borowitz, Adam. "Pichuberries (June 21, 2012)". Article. Tucson Weekly. Retrieved 6 May 2014.(A package purchased in May 2014 was labelled "Product of Colombia")

- ↑ "Groundcherries, (cape-gooseberries or poha), raw, 100 g, USDA Nutrient Database, version SR-21". http://nutritiondata.com. Conde Nast. 2014. Retrieved 7 May 2014. External link in

|website=(help) - ↑ Wu, SJ; Tsai JY; Chang SP; Lin DL; Wang SS; Huang SN; Ng LT (2006). "Supercritical carbon dioxide extract exhibits enhanced antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities of Physalis peruviana". J Ethnopharmacol. 108 (3): 407–13. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2006.05.027. PMID 16820275. Retrieved 2009-01-01.

- ↑ Franco, LA; Matiz GE; Calle J; Pinzón R; Ospina LF (2007). "Antiinflammatory activity of extracts and fractions obtained from Physalis peruviana L. calyces". Biomedica. 27 (1): 110–5. PMID 17546228.

- ↑ Pardo, JM; Fontanilla MR; Ospina LF; Espinosa L. (2008). "Determining the pharmacological activity of Physalis peruviana fruit juice on rabbit eyes and fibroblast primary cultures". Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 7 (7): 3074–9. doi:10.1167/iovs.07-0633. PMID 18579763.

- ↑ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 21169874, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=21169874instead. - ↑ Elissa McCallum (28 July 2014). "Superfood superstars: There's no slowing the quest for the optimum diet. We've fallen for kale, but what's next for superfoods?". Sydney Morning Herald.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 23460435, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=23460435instead. - ↑ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 18922386, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=18922386instead. - ↑ David Segal (26 July 2014). "For Coconut Waters, a Street Fight for Shelf Space". New York Times.

Like kale salads and Robin Thicke, coconut water seems to have jumped from invisible to unavoidable without a pause in the realm of the vaguely familiar.

- ↑ "Do Coconut Water Benefits Include Lowering Cholesterol?". CLevels. Retrieved 14 January 2012.

- ↑ Gibson AC. "Colewart and the cole crops". University of California Los Angeles.

- ↑ "Watercress Nutritional Analysis". Southern Europe Fruits And Vegetables. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ↑ Luc Brouillet. "Taraxacum F. H. Wiggers, Prim. Fl. Holsat. 56. 1780". Flora of North America.

- ↑ "Wild About Dandelions". Mother Earth News.

- ↑ "Dandelion greens, raw". Nutritiondata.com. Retrieved 2011-03-07.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 43.2 43.3 Katrin Schütz, Reinhold Carle & Andreas Schieber; Carle; Schieber (2006). "Taraxacum—a review on its phytochemical and pharmacological profile". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 107 (3): 313–323. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2006.07.021. PMID 16950583.

- ↑ Farnworth, Edward R. (2003). Handbook of Fermented Functional Foods. CRC. ISBN 0-8493-1372-4. Search this book on

- ↑ "Fermented Fruits and Vegetables - A Global SO Perspective". United Nations FAO. 1998. Retrieved 2007-06-10.

- ↑ Allergy Cuisine: Step by Step - Sylvia Ross. p. 94.

- ↑ Dr. Mercola's Total Health Program: The Proven Plan to Prevent Disease and ... - Joseph Mercola, Brian Vaszily, Kendra Pearsall, Nancy Lee Bentley. p. 227.

- ↑ The German Cookbook: A Complete Guide to Mastering Authentic German Cooking - Mimi Sheraton. p. 435.

- ↑ Encyclopedia of Jewish Food - Gil Marks. p. 1052.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 Nutrition Facts and Analysis for Sauerkraut, canned, solids and liquids

- ↑ Lipski, Elizabeth (2013). "6". Digestion Connection: The Simple, Natural Plan to COmbat Diabetes, Heart Disease, Osteoporosis, Arthritis, Acid Reflux--And More!. Rodale. p. 63. ISBN 978-1609619459. Search this book on

- ↑ EurekAlert (2002). "Sauerkraut contains anticancer compound".

- ↑ "Modulation of rat hepatic and kidney phase II enzy... [Br J Nutr. 2011] - PubMed - NCBI". Ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. 2013-03-25. Retrieved 2013-04-19.

- ↑ Moret, Sabrina; Smela, Dana; Populin, Tiziana; Conte, Lanfranco S.; et al. (2005). "A survey on free biogenic amine content of fresh and preserved vegetables". Food Chemistry. Elsevier. 89 (3): 355–361. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2004.02.050.

- ↑ Pu, C.; Xia, C; Xie, C; Li, K; et al. (November 2001). "Research on the dynamic variation and elimination of nitrite content in sauerkraut during pickling". Wei Sheng Yan Jiu. 30 (6): 352–4. PMID 12561618.

- ↑ Wantke, F.; Götz, M; Jarisch, R; et al. (December 1993). "Histamine-free diet: treatment of choice for histamine-induced food intolerance and supporting treatment for chronic headaches". Clinical & Experimental Allergy. Blackwell Publishing. 23 (12): 982–5. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2222.1993.tb00287.x. PMID 10779289.

- ↑ Ward, Mary H.; Pan, WH; Cheng, YJ; Li, FH; Brinton, LA; Chen, CJ; Hsu, MM; Chen, IH; et al. (June 2000). "Dietary exposure to nitrite and nitrosamines and risk of nasopharyngeal carcinoma in Taiwan". International Journal of Cancer. John Wiley & Sons. 86 (5): 603–9. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(20000601)86:5<603::AID-IJC1>3.0.CO;2-H. PMID 10797279.

- ↑ Chang, Ellen T.; Hans-Olov Adami (October 2006). "The Enigmatic Epidemiology of Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma". Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention. 15 (10): 1765–77. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0353. PMID 17035381.

- ↑ Hung, Hsin-chia; Huang, MC; Lee, JM; Wu, DC; Hsu, HK; Wu, MT; et al. (June 2004). "Association between diet and esophageal cancer in Taiwan". Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 19 (6): 632–7. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1746.2004.03346.x. PMID 15151616.

- ↑ Siddiqi, Maqsood; R. Preussmann (1989). "Esophageal cancer in Kashmir — an assessment". Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology. Springer. 115 (2): 111–7. doi:10.1007/BF00397910. PMID 2715165. Retrieved 8 November 2007.

- ↑ Ten Reasons to Eat Fresh Unpasteurized Sauerkraut | Vitality Magazine | Toronto Canada alternative health, natural medicine and green living

- ↑ "List of Foods High in Probiotics". Best Probiotics 2014.

- ↑ Ernst E, Posadzki P, Lee MS (September 2011). "Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) for sexual dysfunction and erectile dysfunction in older men and women: an overview of systematic reviews". Maturitas. 70 (1): 37–41. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2011.06.011. PMID 21782365.CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link)

- ↑ Shin BC, Lee MS, Yang EJ, Lim HS, Ernst E (2010). "Maca (L. meyenii) for improving sexual function: a systematic review". BMC Complement Altern Med. 10: 44. doi:10.1186/1472-6882-10-44. PMC 2928177. PMID 20691074.CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link)

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 "Pharmacognosy and Health Benefits of Cocoa seeds (Chocolate)". pharmaxchange.info.

- ↑ Gressner, Olav A (October 2012). "Chocolate Shake and Blueberry Pie...... or why Your Liver Would Love it". Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology Research. 1 (9): 171–195.

- ↑ 67.0 67.1 67.2 Taubert D, Roesen R, Schömig E (April 2007). "Effect of cocoa and tea intake on blood pressure: a meta-analysis". Arch. Intern. Med. 167 (7): 626–34. doi:10.1001/archinte.167.7.626. PMID 17420419.CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link)

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 Schroeter H, Heiss C, Balzer J; et al. (January 2006). "(-)-Epicatechin mediates beneficial effects of flavanol-rich cocoa on vascular function in humans". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103 (4): 1024–9. doi:10.1073/pnas.0510168103. PMC 1327732. PMID 16418281.CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link)

- ↑ Cocoa: The Next Health Drink?

- ↑ 1743-7075-3-2.fm

- ↑ "Cocoa nutrient for 'lethal ills'". BBC News. 2007-03-11. Retrieved 2010-04-30.

- ↑ Mauro Serafini, Rossana Bugianesi, Giuseppe Maiani, Silvia Valtuena, Somone De Santis, Ala Crozier: "Plasma antioxidants from chocolate", Nature 424(2003)1013. Downloaded from http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/131/01/Crozier,A_2003.pdf

- ↑ J.B. Keogh, J. McInerney, and P.M. Clifton: "The Effect of Milk Protein on the Bioavailability of Cocoa Polyphenols", Journal of Food Science 72(3)S230-S233, 2007. Downloaded from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1750-3841.2007.00314.x/abstract

- ↑ Flavanols in cocoa may offer benefits to the brain

- ↑ Bayard V, Chamorro F, Motta J, Hollenberg NK (2007). "Does flavanol intake influence mortality from nitric oxide-dependent processes? Ischemic heart disease, stroke, diabetes mellitus, and cancer in Panama". Int J Med Sci. 4 (1): 53–8. doi:10.7150/ijms.4.53. PMC 1796954. PMID 17299579.CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link)

- ↑ Messerli FH. "Chocolate Consumption, Cognitive Function, and Nobel Laureates". N Engl J Med. 367: 1562–1564. doi:10.1056/NEJMon1211064.

- ↑ "Cocoa, But Not Tea, May Lower Blood Pressure". ScienceDaily.

- ↑ Taubert, D; Berkels, R; Roesen, R; Klaus, W (2003). "Chocolate and blood pressure in elderly individuals with isolated systolic hypertension". JAMA: the Journal of the American Medical Association. 290 (8): 1029–30. doi:10.1001/jama.290.8.1029. PMID 12941673.

- ↑ Galleano, M; Oteiza, PI; Fraga, CG (2009). "Cocoa, chocolate, and cardiovascular disease". Journal of cardiovascular pharmacology. 54 (6): 483–90. doi:10.1097/FJC.0b013e3181b76787. PMC 2797556. PMID 19701098.

- ↑ Buijsse B, Feskens EJ, Kok FJ, Kromhout D (February 2006). "Cocoa intake, blood pressure, and cardiovascular mortality: the Zutphen Elderly Study". Arch. Intern. Med. 166 (4): 411–7. doi:10.1001/archinte.166.4.411. PMID 16505260.CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link)

- ↑ Guillén, María D.; Ainhoa Ruiz; Nerea Cabo; Rosana Chirinos; Gloria Pascual (August 2003). "Characterization of sacha inchi (Plukenetia volubilis L.) oil by FTIR spectroscopy and 1H NMR. Comparison with linseed oil". Journal of the American Oil Chemists' Society. 80 (8): 755–762. doi:10.1007/s11746-003-0768-z.

- ↑ "Chaga Mushrooms – The Ultimate Superfood and Tonic – Health Benefits of Chaga". Feng Shui London UK • The Capital Feng Shui Consultant.

- ↑ "SuperShrooms Mushrooms The Superfood - Simply Manna". Simply Manna.

- ↑ "Salvia hispanica L." Germplasm Resources Information Network. United States Department of Agriculture. 2000-04-19. Retrieved 21 March 2012.

- ↑ Cahill, Joseph P. (2003). "Ethnobotany of Chia, Salvia hispanica L. (Lamiaceae)". Economic Botany. 57 (4): 604–618. doi:10.1663/0013-0001(2003)057[0604:EOCSHL]2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ Kintzios, Spiridon E. (2000). Sage: The Genus Salvia. CRC Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-90-5823-005-8. Search this book on

- ↑ Stephanie Strom (November 23, 2012). "30 Years After Chia Pets, Seeds Hit Food Aisles". New York Times. Retrieved 26 November 2012.

Whole and ground chia seeds are being added to fruit drinks, snack foods and cereals and sold on their own to be baked into cookies and sprinkled on yogurt. ...

- ↑ 88.0 88.1 USDA SR-21 Nutrient Data (2010). "Nutrition facts for dried chia seeds, one ounce". Conde Nast, Nutrition Data.

- ↑ USDA SR-21 Nutrient Data (2010). "Nutrition Facts and Analysis for Seeds, flaxseed". Conde Nast, Nutrition Data. Retrieved 29 November 2010.

- ↑ USDA SR-21 Nutrient Data (2010). "Nutrition Facts and Analysis for Seeds, sesame seed kernels, dried (decorticated)". Conde Nast, Nutrition Data. Retrieved 29 November 2010.

- ↑ The European Union, "Commission Decision of 13 October 2009 authorising the placing on the market of Chia seed(Salvia hispanica) as a novel food ingredient under Regulation (EC) No 268/97 of the European Parliament and of the Council" (L294/14) 2009/827/EC pp. 14-15 (November 11, 2009)

- ↑ "Chewing Chia Packs A Super Punch". NPR. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ↑ Albergotti, Reed. "The NFL's Top Secret Seed". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 19 October 2012.

- ↑ Ulbricht C; et al. (2009). "Chia (Salvia hispanica): a systematic review by the natural standard research collaboration". Rev Recent Clin Trials. 4 (3): 168–74. doi:10.2174/157488709789957709. PMID 20028328.

- ↑ Stephanie Strom (November 23, 2012). "30 Years After Chia Pets, Seeds Hit Food Aisles". New York Times. Retrieved 26 November 2012.

significantly more alpha-linolenic acid in omega-3 reached the bloodstream and was converted into eicosapentaenoic acid, a long-chain fatty acid considered good for the heart ...

- ↑ Nieman DC, Gillitt N, Jin F, Henson DA, Kennerly K, Shanely RA, Ore B, Su M, Schwartz S (2012). "Chia seed supplementation and disease risk factors in overweight women: a metabolomics investigation". J Altern Complement Med. 18 (7): 700–8. doi:10.1089/acm.2011.0443. PMID 22830971. Retrieved 14 May 2014.CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link)

- ↑ "Meta-analysis of the effects of flaxseed interventions on blood lipids," Pan A, Yu D, Demark-Wahnefried W, Franco OH, Lin X, Am J Clin Nutr. 2009 Aug; 90(2): 288–97.

- ↑ "Iowa State NWRC study finds flaxseed lowers high cholesterol in men". iastate.edu.

- ↑ Chen J, Wang L, Thompson LU (2006). "Flaxseed and its components reduce metastasis after surgical excision of solid human breast tumor in nude mice". Cancer Lett. 234 (2): 168–75. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2005.03.056. PMID 15913884.CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link)

- ↑ Thompson LU, Chen JM, Li T, Strasser-Weippl K, Goss PE (2005). "Dietary flaxseed alters tumor biological markers in postmenopausal breast cancer". Clin. Cancer Res. 11 (10): 3828–35. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2326. PMID 15897583.CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link)

- ↑ 101.0 101.1 "Flaxseed Stunts The Growth Of Prostate Tumors". ScienceDaily. 2007-06-04. Retrieved 2007-11-23.

- ↑ Am J Clin Nutr (March 25, 2009). doi:10.3945/ajcn.2009.26736Ev1

- ↑ Dahl, WJ; Lockert, EA; Cammer, AL; Whiting, SJ (December 2005). "Effects of Flax Fiber on Laxation and Glycemic Response in Healthy Volunteers". Journal of Medicinal Food. 8 (4): 508–511. doi:10.1089/jmf.2005.8.508. PMID 16379563. Retrieved 2007-05-14.

- ↑ Mayo Clinic (2006-05-01). "Drugs and Supplements: Flaxseed and flaxseed oil (Linum usitatissimum)". Retrieved 2007-07-02.

- ↑ "Flaxseed and Flaxseed Oil". National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. Retrieved 2008-01-03.

- ↑ Vogl S, Picker P, Mihaly-Bison J, Fakhrudin N, Atanasov AG, Heiss EH, Wawrosch C, Reznicek G, Dirsch VM, Saukel J, Kopp B. "Ethnopharmacological in vitro studies on Austria's folk medicine - An unexplored lore in vitro anti-inflammatory activities of 71 Austrian traditional herbal drugs." J Ethnopharmacol. 2013 June 13. doi:pii: S0378-8741(13)00410-8. 10.1016/j.jep.2013.06.007. [Epub ahead of print] PubMed PMID 23770053. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23770053

- ↑ "Flaxseed Health Benefits, Food Sources, Recipes, and Tips for Using It". webmd.com.

- ↑ Classic of Poetry. Search this book on

- ↑ "America's First Hemp Drink - Chronic Ice - Making a Splash in the Natural Beverage Market". San Francisco Chronicle. Los Angeles. Vocus. 8 June 2011. Retrieved 19 June 2011.

Chronic Ice, the nation's first drink containing hemp, is making a splash in the healthy beverage market.

[dead link] - ↑ Callaway, J. C. (2004-01-01). "Hempseed as a nutritional resource: An overview" (PDF). Euphytica. Kluwer Academic Publishers. 140 (1–2): 65–72. doi:10.1007/s10681-004-4811-6. Retrieved 2013-03-13.

- ↑ "Characterization, amino acid composition and in vitro digestibility of hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) proteins". Sciencedirect.com. 2008-03-01. Retrieved 2013-11-09.

- ↑ Bensch et al. (2003). Interference of redroot pigweed (Amaranthus retroflexus), Palmer amaranth (A. palmeri), and common waterhemp (A. rudis) in soybean. Weed Science 51: 37-43.

- ↑ Reference Library | WholeHealthMD

- ↑ Ricardo Bressani, Luiz G. Elias and Arnoldo Garcia-Soto (1989). "Limiting amino acids in raw and processed amaranth grain protein from biological tests". Plant foods for human nutrition. Kluwer Academic Publishers. 39 (3): 223–234. doi:10.1007/BF01091933.

- ↑ Kaufmann Weber; et al. (1998). "Advances in New Crops". Purdue University.

- ↑ "Chemical Composition of the Above-ground Biomass of Amaranthus cruentus and A. hypochondriacus" (PDF). ACTA VET. BRNO. 75: 133–138. 2006. doi:10.2754/avb200675010133.

- ↑ "Amaranth - Alternative Field Crops Manual". University of Wisconsin & University of Minneasota. Retrieved September 2011. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - ↑ 10 Reasons to Use Amaranth in Your Gluten-Free Recipes, by Teri Gruss, URL accessed Oct 2009.

- ↑ "The gluten-free vegetarian" (PDF). Practical Gastroenterology: 94–106. May 2007.

- ↑ Gallagher, E.; T. R. Gormley; E. K. Arendt. "Recent advances in the formulation of gluten-free cereal-based products". Trends in Food Science & Technology. 15 (3–4): 143–152. doi:10.1016/j.tifs.2003.09.012. Retrieved 2011-06-26.

- ↑ Czerwiński J, Bartnikowska E, Leontowicz H; et al. (Oct 2004). "Oat (Avena sativa L.) and amaranth (Amaranthus hypochondriacus) meals positively affect plasma lipid profile in rats fed cholesterol-containing diets". J. Nutr. Biochem. 15 (10): 622–9. doi:10.1016/j.jnutbio.2004.06.002. PMID 15542354.CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link)

- ↑ Gonor KV, Pogozheva AV, Derbeneva SA, Mal'tsev GIu, Trushina EN, Mustafina OK (2006). "[The influence of a diet with including amaranth oil on antioxidant and immune status in patients with ischemic heart disease and hyperlipoproteidemia]". Vopr Pitan (in Russian). 75 (6): 30–3. PMID 17313043.CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: Unrecognized language (link)

- ↑ Martirosyan DM, Miroshnichenko LA, Kulakova SN, Pogojeva AV, Zoloedov VI (2007). "Amaranth oil application for coronary heart disease and hypertension". Lipids Health Dis. 6: 1. doi:10.1186/1476-511X-6-1. PMC 1779269. PMID 17207282.CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link)

- ↑ "Legacy - The Official Newsletter of Amaranth Institute; see pages 6-9" (PDF). Amaranth Institute. 1992.

- ↑ "Wild Rice: The Protein-Rich Grain that Almost Nobody Knows About! - Yahoo! Voices - voices.yahoo.com". Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- ↑ "Mother Grain Quinoa A Complete Protein". Oardc.osu.edu. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- ↑ "Nutrition Facts and Analysis of Quinoa, Cooked".

- ↑ "Quinoa". Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- ↑ "Nutritional quality of the protein in quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa, Willd) seeds". ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved Jan 1992. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - ↑ Ray, C. Claiborne (29 December 1998). "Calcium and Quinoa". The New York Times. Retrieved 9 June 2012.

- ↑ Greg Schlick and David L. Bubenheim (November 1993). "Quinoa: An Emerging "New" Crop with Potential for CELSS" (PDF). NASA Technical Paper 3422. NASA.

- ↑ Andrea Cespedes (11 January 2011). "Can You Eat Quinoa Raw or Uncooked?". livestrong.com. Retrieved 16 December 2013.

- ↑ "Anthocyanins Total Polyphenols and Antioxidant Activity in Amaranth and Quinoa Seeds and Sprouts During Their Growth" (PDF). researchgate.net. 12 January 2009. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- ↑ "Horseradish-tree, leafy tips, cooked, boiled, drained, without salt". Nutritiondata.com. Condé Nast. 2012. Retrieved 6 May 2013.

- ↑ K.V. Peter (2008). Underutilized and Underexploited Horticultural Crops:, Volume 4. New India Publishing. p. 112. ISBN 81-89422-90-1. Search this book on

- ↑ Olson, M. E.; Carlquist, S. (2001). "Stem and root anatomical correlations with life form diversity, ecology, and systematics in Moringa (Moringaceae)". Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society. 135 (4): 315–348. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8339.2001.tb00786.x.

This article "List of superfoods" is from Wikipedia. The list of its authors can be seen in its historical. Articles copied from Draft Namespace on Wikipedia could be seen on the Draft Namespace of Wikipedia and not main one.