Protests against the green agenda

| Protests against the green agenda | |

|---|---|

| Part of the Green politics and the 2022 global energy crisis and the economic impact of the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine | |

| Date | 10 June 2022[1] – ongoing (2 years, 6 months, 3 weeks and 4 days) |

| Location | Worldwide |

| Goals |

|

| Methods | |

Protests against the green agenda is a series of social and political protests by various political movements from the extreme left to the extreme right that oppose the current green policy that has implemented certain measures against global warming, and which over time have become protests against the current political establishment, especially in the European Union, which is in the shadow of the Covid-19 pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine suffered the greatest political and economic damage. Protests gained particular ferocity in Western and Central Europe (especially in the Netherlands, Belgium, France and Germany), where fierce clashes between the police and demonstrators took place, and in Southern and Northern Europe, the political establishment was replaced and right-wing populist forces won, while in the UK there was a multi-month government crisis and a series of resignations of even two prime ministers.[2]

Background[edit]

Green politics and Green economics[edit]

Green politics, or ecopolitics, is a political ideology that aims to foster an ecologically sustainable society often, but not always, rooted in environmentalism, nonviolence, social justice and grassroots democracy.[3][4] It began taking shape in the western world in the 1970s; since then Green parties have developed and established themselves in many countries around the globe and have achieved some electoral success.

The political term green was used initially in relation to die Grünen (German for "the Greens"),[5][6] a green party formed in the late 1970s.[7] The term political ecology is sometimes used in academic circles, but it has come to represent an interdisciplinary field of study as the academic discipline offers wide-ranging studies integrating ecological social sciences with political economy in topics such as degradation and marginalization, environmental conflict, conservation and control and environmental identities and social movements.[8][9]

Supporters of green politics share many ideas with the conservation, environmental, feminist and peace movements. In addition to democracy and ecological issues, green politics is concerned with civil liberties, social justice, nonviolence, sometimes variants of localism and tends to support social progressivism.[10] Green party platforms are largely considered left in the political spectrum. The green ideology has connections with various other ecocentric political ideologies, including ecofeminism, eco-socialism and green anarchism, but to what extent these can be seen as forms of green politics is a matter of debate.[11] As the left-wing green political philosophy developed, there also came into separate existence opposite movements on the right-wing that include ecological components such as eco-capitalism and green conservatism.

Global Greens[edit]

The Global Greens (GG) is an international network of political parties and movements which work to implement the Global Greens Charter. It consists of various national Green political parties, partner networks, and other organizations associated with green politics.

Formed in 2001 at the First Global Greens Congress, the network has grown to include 76 full member parties and 11 observers and associate parties as of May 2022, so a total of 87 members. It is governed by a 12-member steering committee called the Global Greens Coordination, and each member party falls under the umbrella of one of four affiliated regional green federations. The day-to-day operations of the Global Greens are managed by the Secretariat, led by Global Greens Convenors Bob Hale and Gloria Polanco since 2020.

2022 global energy crisis[edit]

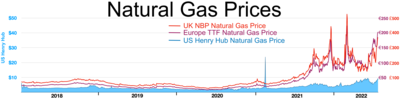

The 2022 global energy crisis began in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2021, with much of the globe facing shortages and increased prices in oil, gas and electricity markets. The crisis was caused by a variety of economic factors, labor shortages, disputes, climate change, and was later compounded by the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Gas shortages in particular have resulted in an increase in food prices and an increase in the use of coal. The response by governments worldwide to the energy crisis have so far been piecemeal and largely ineffectual.

Protests[edit]

Netherlands[edit]

June 2022[edit]

On June 10, 2022, the Dutch government's report on targets for reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in rural areas was published. This was followed by weeks of farmer protests in the Netherlands. This report was published on June 21, 2022.[2] Agricultural and farming organizations said the targets were not realistic and called for a protest in The Hague on 22 June.[13]

On 27 June, protesters blocked a number of highways with tractors and hay bales. Farmers also protested at the provincial government building of North Brabant. Again, there was also a group of farmers who protested at the residence of minister for Nature and Nitrogen Policy Christianne van der Wal.[14] The next day, hay bales were set on fire along several highways.

Protests resumed on 28 June. Among others, there was a demonstration at the House of Representatives, where motions were being voted on. In the evening, there were also protests at the homes of minister Van der Wal and CDA MP Derk Boswijk.[15]

On 29 June, the city of Apeldoorn implemented a state of emergency due to demonstrations and an alleged jailbreak attempt by protestors to free previously arrested activists in custody at the local police station.[16][17]

July 2022[edit]

On 1 July, the city of Harderwijk declared a state of emergency in preparation of a demonstration organized by the anti-establishment protest group Nederland in Verzet (English: Netherlands in Resistance).[18]

On 4 July, farmers began blocking roads with parked vehicles to shut down logistical chains for food distribution, including denying access to supermarkets.[19][20][21] Riot police were called into Heerenveen and deployed tear gas to break up protests.[22]

On 5 July, a canal bridge in Gaarkeuken, Groningen was blocked with around 50 tractors until 6pm, stopping 50 vessels from passing.[23] On the same day, the A37 motorway was briefly blockaded with tractors, resulting in a 2-kilometre traffic jam.[24]

In the evening of 5 July, police fired shots at a 16-year-old youngster driving a tractor after attempting to blockade a highway in Friesland; nobody was injured but the youngster was arrested.[25][26] On July 14, German farmers blocked roads on the border with the Netherlands and gathered in large numbers for protests near the town of Herenburg. On the same day, the protests spread to Poland, Italy, Spain and all the way to India.[27] On 22 July, the Dutch Department of Justice announced the start of a criminal investigation into the incident, concerning whether the actions of the officer in question constituted attempted murder.[28] Also in July, some fishermen began blockading ports in solidarity with the farmers.[29][30]

At the end of July, several farmers dumped waste on highways, especially on the A18. This caused accidents, and motorists who wanted to clean up the waste were verbally abused by the farmers and threatened with violence.[31] At least one farmer was caught in flagrante and received a community service order of 80 hours, a suspended prison sentence of one week, and a claim of more than 3,000 euros for expenses incurred by Rijkswaterstaat.[32] Another farmer was sentenced to 100 hours of community service, a suspended 60 days prison term, and a claim of damages amounting to 3,600 euros.[33]

August 2022[edit]

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (August 2022) |

September 2022[edit]

On 20 September, tens of farmers attempted to enter the city center of The Hague with their tractors to protest during Prinsjesdag, in defiance of a state of emergency declared for the duration of festivities.[34] Consequently, authorities confiscated six vehicles and arrested five protesters.[35] Both mayor Jan van Zanen and minister of Justice and Security Dilan Yeşilgöz-Zegerius emphasized that the farmers were allowed to protest, but without heavy equipment.[36]

On 23 September, ten farmers who had protested at the home of minister Van der Wal on the evening of 28 June were sentenced to community service orders of 60 to 100 hours, eight of whom also received suspended prison terms of up to a month. An eleventh protester, a minor, is to serve 80 hours of community service.[37] The Public Prosecution Service has yet to announce charges against an additional 24 suspects who were arrested since the return of protests in the summer of 2022.[38]

Belgium[edit]

On June 20, around 70,000 Belgian workers marched in Brussels demanding government action to tackle skyrocketing living costs, as one-day strikes at Brussels airport and on local transport networks across the country brought public travel to a near standstill. Demonstrators carried flags and banners reading "More respect, higher wages" and "Abolish excise taxes", while some lit torches. Some demanded the government do more, others said employers needed to improve wages and working conditions.[39]

Thousands of people gathered in the Belgian capital Brussels on September 21 for a "National Day of Action" to protest against the spikes in electricity, natural gas and food prices and draw attention to the sharp rise in the cost of living. Unions and city police said about 10,000 took part. People from all over the country rallied, marching behind banners reading "Life is too expensive, we want solutions now" and "Everything is going up except our wages" or carrying placards reading "Freeze prices, not people". City traffic and public transport were interrupted.[40]

Germany[edit]

On July 13, German farmers blocked roads on the border with the Netherlands and gathered in large numbers for protests near the town of Herenburg.[27] On July 18, German farmers blocked the western border with the Netherlands again, thus supporting the Dutch farmers.[41] A farmers' protest was held in the center of Bonn on August 15, and the level of security was increased. Several hundred farmers, accompanied by around 200 tractors, protested in front of the Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture on Rochusstrasse in Bonn. Police closed Rochusstrasse to vehicular traffic between Villemombler Straße and Provinzialstraße to facilitate the demonstration. Organizers condemned EU plans to reduce the use of pesticides in agriculture.[42]

France[edit]

Yellow vest activists renewed their protests on September 3 at the Place de la Republique in Paris against further financial aid to Ukraine and poor social standards.[43] The next major protests took place on September 17 in central Paris and lasted into the evening as thousands of activists associated with the Gilets Jaunes organized an anti-government protest march on the Place du Palais Royal in Paris and called for the resignation of President Emmanuel Macron and a protest against a variety of grievances, including COVID-19 vaccine mandates, the rising cost of living, and international issues, among others.[44] The Yellow Vest Movement organized protests again in Paris, France on October 1.[45]

Protests against inflation[edit]

The first demonstrations days was marked on 16 October 2022, when tens of thousands of people marched in Paris to protest the rising cost of living, during an increasing political situation manifested by strikes at oil refineries and nuclear power plants that threaten to spread.[46] Annie Ernaux, winner of the 2022 Nobel Prize in Literature, known for as an "outspoken supporter of the left", participated the demonstrations. Jean-Luc Melenchon, the leader of hard-left party La France Insoumise (France Unbowed), was also among the participants. On Tuesday, transportation workers, as well as some high school teachers and public hospital personnel, demonstrated in dozens of locations across France. According to the French interior minister, 107,000 people participated in the protests following the calls from the leftwing parties. A number of black-clad protesters clashed with the Police and smashed the shop windows with 11 protesters being arrested in Paris. Other estimates stated that over 300,000 people participated in the protests.[47] Accordingly, thousands protested in Bordeaux, Le Havre, Lille, Marseille, Lyon, Toulouse, and Rennes, while union leaders estimated that 70,000 people marched in Paris.[47]

Students protested outside hundreds of additional schools across the nation on Tuesday morning. Protesting students voiced their support for striking refinery workers and opposition to the Macron administration's policies. "We are here against the repression and police violence that are only increasing," said a student speaking to L’Est Republicain.[48] Numerous students also demonstrated in opposition to the government's discriminatory anti-Muslim legislation and deepening gabs to national education. In French public schools, young Muslim women are strictly prohibited to cover their hair or face using any type of fabric.[48]

Italy[edit]

July[edit]

In Milan, on July 8, Italian farmers in a column of tractors also blocked city traffic, and the protests spread to most of the country in the following days.[49][50] On 14 July, despite having largely won the confidence vote, Prime Minister Draghi offered his resignation, which was rejected by President Sergio Mattarella.[51][52][53] On July 21, Italian Prime Minister Mario Draghi tendered his irrevocable resignation and returned the mandate to Italian President Sergio Mattarella, who called early parliamentary elections for September 25.

September[edit]

On September 13, Italian farmers gathered again in the city of Caserta to protest the forced slaughter of livestock and the increase in energy prices. Hundreds of tractors massively blocked Caserta in protest against the forced slaughter of 140,000 cattle and the increase in energy prices. The reason for the protests was after 400 companies went bankrupt and 8,000 jobs were lost.[54] In the 2022 Italian general election held on 25 September 2022, a center-right coalition led by the Italian Brothers Giorgio Meloni, a radical-right political party with neo-fascist roots,[55][56][57][58] won an absolute majority of seats in Italy Parliament. Meloni was appointed Prime Minister of Italy on 22 October, becoming the first woman to hold the post.[59]

United Kingdom[edit]

Spain[edit]

Farmers in Spain joined mass European protests on July 15.[60]

Poland[edit]

Polish farmers also protested on July 13 due to the allowed costs of importing fertilizers and cheap food, thereby increasing the cost of local production. Farmers took to the streets of Warsaw shouting slogans: "Enough is enough!" We will not allow them to rob us!” and "We workers cannot pay for a crisis created by politicians!"

Czech Republic[edit]

Czech Republic First! (Czech: Česká republika na 1. místě!)[61] was a mass public demonstration on 3 September 2022 in Wenceslas Square in Prague,[62] expressing dissatisfaction with the government of Petr Fiala and the government's approach to the ongoing energy crisis, inflation, and the Russian invasion of Ukraine.[63] According to police, about 70,000 people took part in the demonstration.[64] A number of politicians and activists participated in the protest or expressed their support for the protesters.[63]

Slovakia[edit]

Several thousand demonstrators took to the streets of Slovakia's two largest cities on September 1 to protest government and pandemic restrictions on Wednesday, the day the country celebrated Constitution Day. The protests were organized by opposition parties and extremists, who jointly called for early parliamentary elections. About 6,000 people participated in the anti-government protest organized by the opposition party Smer in the center of Košice. At the same time, a separate protest of the far-right Republican Party was organized in a nearby street. Former Prime Minister Robert Fico also addressed the crowd, referring to some measures against the COVID-19 epidemic. Former president Ivan Gašparovič was also on stage. Fico also criticized President Zuzana Čaputová for refusing to call a referendum on early elections. Instead, Čaputova turned to the constitutional court, which decided that the referendum would not be in accordance with the constitution. The protests in Bratislava, called by the extremist LSNS party, were more violent. Demonstrators blocked traffic in several streets in the center of the capital and clashed with the police, who were forced to use water cannons and tear gas against them. Three people were detained by the police, while three others were injured.[65] Several thousand people gathered in the Slovak capital on September 20 to protest against the government over the spike in energy prices and demand early elections. The protest was organized by former populist Prime Minister Robert Fico left-wing opposition Smer-Social Democracy party and included supporters of other groups, including the far right. Most speakers attacked the European Union's sanctions against Russia and praised Hungary's handling of the energy crisis.[66]

See also[edit]

- Green politics

- Dutch farmers' protests

- 2022 Europe inflation protests

- Regional effects of the 2021–2022 global energy crisis

- 2021–2022 global energy crisis

- 2022 food crises

References[edit]

- ↑ "Netherlands: 2022 Dutch Farmer Protests Against New Nitrogen GHG Emissions Reductions Policies". Foreign Agricultural Service. 10 June 2022. Archived from the original on 25 September 2022. Retrieved 3 November 2022. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Netherlands: 2022 Dutch Farmer Protests Against New Nitrogen GHG Emissions Reductions Policies". USDA Foreign Agricultural Service.

- ↑ Wall 2010. p. 12-13.

- ↑ Peter Reed; David Rothenberg (1993). Wisdom in the Open Air: The Norwegian Roots of Deep Ecology. University of Minnesota Press. p. 84. ISBN 978-0-8166-2182-8. Search this book on

- ↑ Derek Wall (2010). The No-nonsense Guide to Green Politics. New Internationalist. p. 12. ISBN 978-1-906523-39-8. Search this book on

- ↑ Jon Burchell (2002). The Evolution of Green Politics: Development and Change Within European Green Parties. Earthscan. p. 52. ISBN 978-1-85383-751-7. Search this book on

- ↑ Playing by the Rules: The Impact of Electoral Systems on Emerging Green Parties. 2007. p. 79. ISBN 978-0-549-13249-3. Search this book on

- ↑ Robbins, Paul (2012). Political Ecology: A Critical Introduction. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 9780470657324. Search this book on

- ↑ Peet, Richard; Watts, Michael (2004). Liberation Ecologies: Environment, Development, Social Movements. Routledge. p. 6. ISBN 9780415312363. Search this book on

- ↑ Dustin Mulvaney (2011). Green Politics, An A-to-Z Guide. SAGE publications. p. 394. ISBN 9781412996792. Search this book on

- ↑ Wall 2010. p. 47-66.

- ↑ Heyden, Wies van der (1 August 2022). "Weghalen of laten hangen? Zo denken mensen over de omgekeerde Nederlandse vlag" (in Nederlands). EenVandaag. Retrieved 14 August 2022.

- ↑ "Dutch gov't sets targets to cut nitrogen pollution, farmers to protest". Reuters. June 10, 2022 – via www.reuters.com.

- ↑ "Boeren steken brandstapels aan op A1 en A50 • Kort protest bij woning stikstofminister". Nederlandse Omroep Stichting (in Nederlands). 27 June 2022. Retrieved 14 August 2022.

- ↑ "CDA'er blijft thuis na protest boeren, Kamerleden krijgen veiligheidsinstructies". Nederlandse Omroep Stichting (in Nederlands). 29 June 2022. Retrieved 14 August 2022.

- ↑ "Police prevent farmers' jail break attempt in Apeldoorn". NL Times. Archived from the original on 2022-07-08. Retrieved 2022-07-06. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ "Apeldoorn vaardigt noodverordening uit - Gemeente Apeldoorn". www.apeldoorn.nl (in Dutch). Archived from the original on 2022-07-08. Retrieved 2022-07-06. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help)CS1 maint: Unrecognized language (link) - ↑ "Demonstratie vanavond gaat door". Gemeente Harderwijk. 1 July 2022. Archived from the original on 1 July 2022.

- ↑ "Police fire on Dutch farmers protesting environmental rules". POLITICO. 2022-07-06. Archived from the original on 2022-07-06. Retrieved 2022-07-06. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ Bennicke, Helen (2022-07-04). "Crisis rages on in the Netherlands as farmers block food warehouses over emission rules". Express.co.uk. Retrieved 2022-07-06.

- ↑ "Dutch farmers and fishermen block roads to protest emissions cuts". euronews. 2022-07-05. Retrieved 2022-07-06.

- ↑ "ME bekogeld door boeren in Heerenveen: traangas ingezet". Telegraaf (in Nederlands). 2022-07-04. Archived from the original on 2022-07-05. Retrieved 2022-07-06. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ "Farmers' blockades 'will cost supermarkets tens of millions'". DutchNews.nl. 2022-07-06. Archived from the original on 2022-07-08. Retrieved 2022-07-06. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ "Politie schiet gericht op trekker op oprit A32 Heerenveen, niemand gewond". nos.nl (in Dutch). 5 July 2022. Archived from the original on 2022-07-08. Retrieved 2022-07-06. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help)CS1 maint: Unrecognized language (link) - ↑ "Dutch police shoot at tractor during night of farm protests". The Washington Post. July 6, 2022. Archived from the original on July 7, 2022. Retrieved July 6, 2022. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ "'Politie schoot op 16-jarige trekkerbestuurder', boeren eisen bij bureau vrijlating". NOS (in Nederlands). July 6, 2022. Retrieved July 30, 2022. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ 27.0 27.1 "Farmer protests spread across the globe". The Scottish Farmer. 2022-07-14. Archived from the original on 2022-07-14. Retrieved 2022-10-24. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ "'OM opent strafrechtelijk onderzoek naar agent die op 16-jarige Jouke schoot'". NRC (in Nederlands). 22 July 2022. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ↑ "Dutch fishermen protest with port blockade - FiskerForum". FiskerForum.dk. 2022-07-04. Archived from the original on 2022-07-04. Retrieved 2022-07-06. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ Karremann, Jaime. "Vissers blokkeerden marinehaven Den Helder enkele uren". Marineschepen.nl (in Dutch). Archived from the original on 2022-07-04. Retrieved 2022-07-06. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help)CS1 maint: Unrecognized language (link) - ↑ "Ongelukken door acties van boeren op de weg". Jeugdjournaal (in Nederlands). 28 July 2022. Retrieved 14 August 2022.

- ↑ "Boer die afval op A18 dumpte krijgt 80 uur taakstraf". ThePostOnline (in Nederlands). 11 August 2022. Retrieved 14 August 2022.

- ↑ "Boer krijgt zestig dagen celstraf voor organiseren van blokkade op A18". NU.nl (in Nederlands). 18 August 2022. Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- ↑ "Boerenprotest op Prinsjesdag: 40 trekkers op weg naar Den Haag ondanks noodbevel". RTL Nieuws (in Nederlands). 20 September 2022. Retrieved 20 September 2022.

- ↑ "Vijf mensen opgepakt op Prinsjesdag, zes tractoren meegenomen". Leidsch Dagblad (in Nederlands). 20 September 2022. Retrieved 20 September 2022.

- ↑ "Boeren negeren noodbevel Den Haag, trekkers in beslag genomen". Nederlandse Omroep Stichting (in Nederlands). 20 September 2022. Retrieved 20 September 2022.

- ↑ Piekartz, Hessel von; Gruijter, Wies de (23 September 2022). "Tot 100 uur taakstraf voor demonstrerende boeren die minister Van der Wal thuis intimideerden". de Volkskrant (in Nederlands). Retrieved 23 September 2022.

- ↑ "Werkstraffen tot 100 uur voor protest bij huis minister Van der Wal". Nederlandse Omroep Stichting (in Nederlands). 23 September 2022. Retrieved 23 September 2022.

- ↑ "Brussels at near-standstill as cost-of-living march draws 70,000". Reuters. June 20, 2022 – via www.reuters.com.

- ↑ "Thousands rally in Belgium to protest high energy prices". AP NEWS. September 21, 2022.

- ↑ "Why farmers' protests that kicked off in The Netherlands are spreading across Europe". Firstpost. July 18, 2022.

- ↑ "Germany: Farmers' protest ongoing in central Bonn Aug. 15". Germany: Farmers' protest ongoing in central Bonn Aug. 15 | Crisis24.

- ↑ "France: Activists to protest in Place de la Republique, Paris, Sept. 3". France: Activists to protest in Place de la Republique, Paris, Sept. 3 | Crisis24.

- ↑ "France: Further disruptions likely through the evening of Sept. 17 amid protest at Place du Palais Royal in Paris". France: Further disruptions likely through the evening of Sept. 17 amid protest at Place du Palais Royal in Paris | Crisis24.

- ↑ "France: Yellow Vests movement to stage protests in Paris, Oct. 1". France: Yellow Vests movement to stage protests in Paris, Oct. 1 | Crisis24.

- ↑ Méheut, Constant (2022-10-16). "Tens of Thousands March in Paris to Protest Rising Living Costs". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2022-10-19.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 "French police assault workers marching against inflation and in support of refinery strike". World Socialist Web Site. Retrieved 2022-10-26.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 "French high school students stage mass walkout in solidarity with striking refinery workers". World Socialist Web Site. Retrieved 2022-10-20.

- ↑ Manning, Joshua (July 8, 2022). "WATCH: Farmers in Poland and Italy join Netherlands in mass European protests".

- ↑ Marsi, Federica. "Farmers watch crops wither amid Italy's worst drought in 70 years". www.aljazeera.com.

- ↑ Harlan, Chico; Pitrelli, Stefano (14 July 2022). "Italy in crisis as president rejects premier Draghi's offer to resign". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 14 July 2022. Retrieved 15 July 2022. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ "Mattarella respinge dimissioni Draghi e manda premier a Camere – Ultima Ora" (in italiano). ANSA. 14 July 2022. Archived from the original on 14 July 2022. Retrieved 15 July 2022. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ "Four scenarios: What happens next in Italy's government crisis?". The Local Italy. 17 July 2022. Archived from the original on 18 July 2022. Retrieved 21 July 2022. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ Manning, Joshua (September 14, 2022). "WATCH: Italian farmers protest forced slaughter of cattle and energy price increase".

- ↑ "Italy's Mattarella dissolves parliament, election set for 25 September". Euronews. 21 July 2022. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- ↑ Donà, Alessia (31 August 2022). "The Rise of the Radical Right in Italy: The Case of Fratelli d'Italia". Journal of Modern Italian Studies. Taylor & Francis. 27 (5): 775–794. doi:10.1080/1354571X.2022.2113216. hdl:11572/352744. Unknown parameter

|s2cid=ignored (help) - ↑ Gautheret, Jérôme (25 September 2022). "The unstoppable rise of Giorgia Meloni, the new figurehead of the Italian radical right". Le Monde. Retrieved 28 September 2022.

- ↑ Winfield, Nicole (26 September 2022). "How a party of neo-fascist roots won big in Italy". AP News. Associated Press. Retrieved 30 September 2022.

- ↑ Amante, Angelo; Balmer, Crispian (22 October 2022). "Right-wing Meloni sworn in as Italy's first woman prime minister". Reuters. Retrieved 25 October 2022.

- ↑ Manning, Joshua (July 15, 2022). "WATCH: Farmers in Spain join Italy, Poland, and Netherlands in mass European protests".

- ↑ "Organizátoři". Česko na prvním místě.

- ↑ "Přehled oznámených veřejných shromáždění". Portál hlavního města Prahy. Retrieved 29 August 2022.

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 "Česká republika na 1. místě - mír a prosperitu, ne válku a bídu". Česko na prvním místě. Retrieved 29 August 2022.

- ↑ "Na tříhodinový protest proti vládě přišlo v Praze asi 70.000 lidí". České noviny. 3 September 2022.

- ↑ Koreň, Marián (September 2, 2021). "Anti-government protests take place in Slovakia's two largest cities". www.euractiv.com.

- ↑ [usnews.com/news/world/articles/2022-09-20/thousands-protest-slovak-government-demand-early-election Thousands Protest Slovak Government, Demand Early Election]

This article "Protests against the green agenda" is from Wikipedia. The list of its authors can be seen in its historical and/or the page Edithistory:Protests against the green agenda. Articles copied from Draft Namespace on Wikipedia could be seen on the Draft Namespace of Wikipedia and not main one.