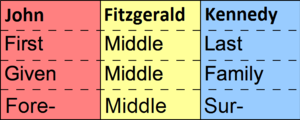

Surname

In some cultures, a surname, family name, or last name is the portion of one's personal name that indicates one's family, tribe or community.[1]

Practices vary by culture. The family name may be placed at either the start of a person's full name, as the forename, or at the end; the number of surnames given to an individual also varies. As the surname indicates genetic inheritance, all members of a family unit may have identical surnames or there may be variations; for example, a woman might marry and have a child, but later remarry and have another child by a different father, and as such both children could have different surnames. It is common to see two or more words in a surname, such as in compound surnames. Compound surnames can be composed of separate names, such as in traditional Spanish culture, they can be hyphenated together, or may contain prefixes.

Using names has been documented in even the oldest historical records. Examples of surnames are documented in the 11th century by the barons in England. English surnames began as a way of identifying a certain aspect of that individual, such as by trade, father's name, location of birth, or physical features, and were not necessarily inherited. By 1400 most English families, and those from Lowland Scotland, had adopted the use of hereditary surnames.[2]

Definition of a surname[edit]

In the Anglophonic world, a surname is commonly referred to as the last name because it is usually placed at the end of a person's full name, after any given name. In many parts of Asia and in some parts of Europe and Africa, the family name is placed before a person's given name. In most Spanish-speaking and Portuguese-speaking countries, two surnames are commonly used or, in some families, three or even more, often because of family claims to nobility.

Surnames have not always existed and are still not universal in some cultures. The tradition has arisen separately in different cultures around the world. In Europe, the concept of surnames became popular in the Roman Empire and expanded throughout the Mediterranean and Western Europe as a result. During the Middle Ages, that practice died out as Germanic, Persian and other influences took hold. During the late Middle Ages surnames gradually re-emerged, first in the form of bynames, which typically indicated an individual's occupation or area of residence, and gradually evolving into modern surnames. In China surnames have been the norm since at least the 2nd century BC.[3]

A family name is typically a part of a person's personal name and, according to law or custom, is passed or given to children from at least one of their parents' family names. The use of family names is common in most cultures around the world, but each culture has its own rules as to how the names are formed, passed, and used. However, the style of having both a family name (surname) and a given name (forename) is far from universal (see §History below). In many cultures, it is common for people to have one name or mononym, with some cultures not using family names. In most Slavic countries and in Greece, Lithuania and Latvia, for example, there are different family name forms for male and female members of the family. Issues of family name arise especially on the passing of a name to a newborn child, the adoption of a common family name on marriage, the renunciation of a family name, and the changing of a family name.

Surname laws vary around the world. Traditionally in many European countries for the past few hundred years, it was the custom or the law for a woman, upon marriage, to use her husband's surname and for any children born to bear the father's surname. If a child's paternity was not known, or if the putative father denied paternity, the newborn child would have the surname of the mother. That is still the custom or law in many countries. The surname for children of married parents is usually inherited from the father.[4] In recent years, there has been a trend towards equality of treatment in relation to family names, with women being not automatically required, expected or, in some places, even forbidden, to take the husband's surname on marriage, with the children not automatically being given the father's surname. In this article, both family name and surname mean the patrilineal surname, which is handed down from or inherited from the father, unless it is explicitly stated otherwise. Thus, the term "maternal surname" means the patrilineal surname that one's mother inherited from either or both of her parents. For a discussion of matrilineal ('mother-line') surnames, passing from mothers to daughters, see matrilineal surname.

The study of proper names (in family names, personal names, or places) is called onomastics. A one-name study is a collection of vital and other biographical data about all persons worldwide sharing a particular surname.

History[edit]

Origins[edit]

While the use of given names to identify individuals is attested in the oldest historical records, the advent of surnames is a relatively recent phenomenon.[5] Many cultures have used and continue to use additional descriptive terms in identifying individuals. These terms may indicate personal attributes, location of origin, occupation, parentage, patronage, adoption, or clan affiliation. These descriptors often developed into fixed clan identifications that in turn became family names as we know them today.

In China, according to legend, family names started with Emperor Fu Xi in 2000 BC.[6][unreliable source?][7] His administration standardised the naming system in order to facilitate census-taking, and the use of census information. Originally, Chinese surnames were derived matrilineally,[8] although by the time of the Shang dynasty (1600 to 1046 BCE) they had become patrilineal.[8][9] Chinese women do not change their names upon marriage. They can be referred to either as their full birth names or as their husband's surname plus the word for wife. In the past, women's given names were often not publicly known and women were referred in official documents by their family name plus the character "Shi" and when married by their husband's surname, their birth surname, and the character "Shi".[citation needed]

In the Middle East surnames have been and are still of great importance. An early form of tribal nisbas is attested among Amorite and Aramean tribes in the early Bronze and Iron ages as early as 1800 BC.

In ancient Iran, surnames were used, but it is likely that most of them belonged to the aristocracy, nobility and military leaders. Among the most famous historical houses were the Achaemenids, the Arsacids, and the Sasanians. These nobilities would have been recognised by their seals, coat of Arms and banners, which Shahnameh or the Book of Kings, provides a good source of information about them.

In the early Islamic period (640-900 CE) and the Arab world, the use of patronymics is well attested. The famous scholar Rhazes (c. 865–925 CE) is referred to as "al-Razi" (lit. the one from Ray) due to his origins from the city of Ray, Iran. In the Levant, surnames were in use as early as the High Middle Ages and it was common for people to derive their surname from a distant ancestor, and historically the surname would be often preceded with 'ibn' or 'son of'. Arab family names often denote either one's tribe, profession, a famous ancestor, or the place of origin; but they weren't universal. For example, Hunayn ibn Ishaq (fl. 850 CE) was known by the nisbah "al-'Ibadi", a federation of Arab Christian tribes that lived in Mesopotamia prior to the advent of Islam. Hamdan ibn al-Ash'ath (fl. 874 CE), the founder of Qarmatian Isma'ilism, was surnamed "Qarmat", an Aramaic word which probably meant "red-eyed" or "Short-legged".

In Ancient Greece, as far back as the Archaic Period clan names and patronymics ("son of") were also common, as in Aristides as Λῡσῐμᾰ́χου - son of Lysimachus. For example, Alexander the Great was known as Heracleides, as a supposed descendant of Heracles, and by the dynastic name Karanos/Caranus, which referred to the founder of the dynasty to which he belonged. These patronymics are already attested for many characters in the works of Homer. At other times formal identification commonly included the place of origin.[10] In none of these cases, though, were these names considered essential parts of the person's name, nor were they explicitly inherited in the manner that is common in many cultures today.

In the Roman Republic and later Empire, the use of different naming conventions went through multiple changes over its history. (See Roman naming conventions.) The nomen, the name of the gens inherited patrilineally, are thought to have been in use already by 650 BC.[11] The nomen was to identify group kinship, while the praenomen was used to distinguish individuals. Female praenomen were less common, as women had reduced public influence, and were commonly known by the feminine form of the nomen alone. Some women were distinguished from relatives later on by the use of major/minor. The number of commonly used praenomen was severely restricted, with some falling out of use and very few new names gaining popularity. During the republic, 99% of Romans shared one of 17 praenomen.[11] In addition eldest sons were frequently given the same praenomen as their father. The result was that there was reduced distinction between members of the same gens. Therefore from the 5th to the 2nd centuries BC the use of cognomen arose, beginning in noble patrician families. These were originally personal names, frequently physical features. For example the cognomen of Pūblius Ovidius Nāsō meaning "nose". In time cognomen were again inherited and ceased to be personal distinguishers. In the later centuries of the empire, there was a proliferation of similar agnomen for further distinction.

Later with the gradual influence of Greek and Christian culture throughout the Empire, Christian religious names were sometimes put in front of traditional cognomens, but eventually people reverted to single names.[12] By the time of the fall of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century, family names were uncommon in the Eastern Roman Empire. In Western Europe, where Germanic culture dominated the aristocracy, family names were almost non-existent. They would not significantly reappear again in Eastern Roman society until the 10th century, apparently influenced by the familial affiliations of the Armenian military aristocracy.[12] The practice of using family names spread through the Eastern Roman Empire and gradually into Western Europe, although it was not until the modern era that family names came to be explicitly inherited as they are today.

In medieval Spain, a patronymic system was used. For example, Álvaro, the son of Rodrigo would be named Álvaro Rodríguez. His son, Juan, would not be named Juan Rodríguez, but Juan Álvarez. Over time, many of these patronymics became family names and are some of the most common names in the Spanish-speaking world. Other sources of surnames are personal appearance or habit, e.g. Delgado ("thin") and Moreno ("dark"); geographic location or ethnicity, e.g. Alemán ("German"); or occupations, e.g. Molinero ("miller"), Zapatero ("shoe-maker") and Guerrero ("warrior"), although occupational names are much more often found in a shortened form referring to the trade itself, e.g. Molina ("mill"), Guerra ("war"), or Zapata (archaic form of zapato, "shoe").

In England, the introduction of family names is generally attributed to the preparation of the Domesday Book in 1086,[13] following the Norman conquest. Evidence indicates that surnames were first adopted among the feudal nobility and gentry, and slowly spread to other parts of society. Some of the early Norman nobility who arrived in England during the Norman conquest differentiated themselves by affixing 'de' (of) before the name of their village in France. This is what is known as a territorial surname, a consequence of feudal landownership. By the 14th century, most English and most Scottish people used surnames and in Wales following unification under Henry VIII in 1536.[14]

A four-year study led by the University of the West of England, which concluded in 2016, analysed sources dating from the 11th to the 19th century to explain the origins of the surnames in the British Isles.[15] The study found that over 90% of the 45,602 surnames in the dictionary are native to Britain and Ireland, with the most common in the UK being Smith, Jones, Williams, Brown, Taylor, Davies, and Wilson.[16] The findings have been published in the Oxford English Dictionary of Family Names in Britain and Ireland, with project leader, Professor Richard Coates calling the study "more detailed and accurate" than those before.[15] He elaborated on the origins; "Some surnames have origins that are occupational – obvious examples are Smith and Baker. Other names can be linked to a place, for example, Hill or Green, which relates to a village green. Surnames that are 'patronymic' are those which originally enshrined the father's name – such as Jackson, or Jenkinson. There are also names where the origin describes the original bearer such as Brown, Short, or Thin – though Short may in fact be an ironic 'nickname' surname for a tall person."[15]

Modern era[edit]

During the modern era, many cultures around the world adopted family names, particularly for administrative reasons, especially during the age of European expansion and particularly since 1600. Notable examples include the Netherlands (1795–1811), Japan (1870s), Thailand (1920), and Turkey (1934). The structure of the Japanese name was formalized by the government as family name + given name in 1868.[17] Nonetheless, the use of surnames is not universal: Icelanders, Burmese, Javanese, and many people groups in East Africa do not use family names.

Family names sometimes change or are replaced by non-family-name surnames under political pressure to avoid persecution.[citation needed] Examples are the cases with Chinese Indonesians and Chinese Thais after migration there during the 20th century or the Jews who fled to different European countries to avoid persecution from the Nazis during World War II. Other ethnic groups have been forced to change or adapt surnames to conform with the cultural norms of the dominant culture, such as in the case of enslaved people and indigenous people of the Americas.

Family name discrimination against women[edit]

Henry VIII (ruled 1509–1547) ordered that marital births be recorded under the surname of the father.[5] In England and cultures derived from there, there has long been a tradition for a woman to change her surname upon marriage from her birth name to her husband's family name. (See Maiden and married names.)

In the Middle Ages, when a man from a lower-status family married an only daughter from a higher-status family, he would often adopt the wife's family name.[citation needed] In the 18th and 19th centuries in Britain, bequests were sometimes made contingent upon a man's changing (or hyphenating) his family name, so that the name of the testator continued.

The United States followed the naming customs and practices of English common law and traditions until recent[when?] times. The first known instance in the United States of a woman insisting on the use of her birth name was that of Lucy Stone in 1855, and there has been a general increase in the rate of women using their birth name. Beginning in the latter half of the 20th century, traditional naming practices writes one commentator, were recognized as "com[ing] into conflict with current sensitivities about children's and women's rights".[18] Those changes accelerated a shift away from the interests of the parents to a focus on the best interests of the child. The law in this area continues to evolve today mainly in the context of paternity and custody actions.[19]

Naming conventions in the US have gone through periods of flux, however, and the 1990s saw a decline in the percentage of name retention among women.[citation needed] As of 2006, more than 80% of American women adopted the husband's family name after marriage.[20]

It is rare but not unknown for an English-speaking man to take his wife's family name, whether for personal reasons or as a matter of tradition (such as among matrilineal Canadian aboriginal groups, such as the Haida and Gitxsan). Upon marriage to a woman, men in the United States can change their surnames to that of their wives, or adopt a combination of both names with the federal government, through the Social Security Administration. Men may face difficulty doing so on the state level in some states.

It is exceedingly rare but does occur in the United States, where a married couple may choose an entirely new last name by going through a legal change of name. As an alternative, both spouses may adopt a double-barrelled name. For instance, when John Smith and Mary Jones marry each other, they may become known as "John Smith-Jones" and "Mary Smith-Jones". A spouse may also opt to use their birth name as a middle name, and e.g. become known as "Mary Jones Smith".[citation needed] An additional option, although rarely practiced[citation needed], is the adoption of the last name derived from a blend of the prior names, such as "Simones", which also requires a legal name change. Some couples keep their own last names but give their children hyphenated or combined surnames.[21]

In 1979, the United Nations adopted the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women ("CEDAW"), which declared in effect that women and men, and specifically wife and husband, shall have the same rights to choose a "family name", as well as a profession and an occupation.[22]

In some places, civil rights lawsuits or constitutional amendments changed the law so that men could also easily change their married names (e.g., in British Columbia and California).[23] Québec law permits neither spouse to change surnames.[24]

In France, until 1 January 2005, children were required by law to take the surname of their father. Article 311-21 of the French Civil code now permits parents to give their children the family name of either their father, mother, or hyphenation of both – although no more than two names can be hyphenated. In cases of disagreement, both names are used in alphabetical order.[25] This brought France into line with a 1978 declaration by the Council of Europe requiring member governments to take measures to adopt equality of rights in the transmission of family names, a measure that was echoed by the United Nations in 1979.[26]

Similar measures were adopted by West Germany (1976), Sweden (1982), Denmark (1983), and Spain (1999). The European Community has been active in eliminating gender discrimination. Several cases concerning discrimination in family names have reached the courts. Burghartz v. Switzerland challenged the lack of an option for husbands to add the wife's surname to his surname, which they had chosen as the family name when this option was available for women.[27] Losonci Rose and Rose v. Switzerland challenged a prohibition on foreign men married to Swiss women keeping their surname if this option was provided in their national law, an option available to women.[28] Ünal Tekeli v. Turkey challenged prohibitions on women using their surname as the family name, an option only available to men.[29] The Court found all these laws to be in violation of the convention.[30]

From 1945 to 2021 in the Czech Republic women by a law had to use family names with the ending -ová behind the name of their father or husband (so-called přechýlení). This was seen as discriminatory by a part of the public. Since 1 January 2022, Czech women can decide for themselves whether they want to use the feminine or masculine form of their family name. [31]

Patronymic surnames[edit]

These are the oldest and most common type of surname.[32] They may be a first name such as "Wilhelm", a patronymic such as "Andersen", a matronymic such as "Beaton", or a clan name such as "O'Brien". Multiple surnames may be derived from a single given name: e.g. there are thought to be over 90 Italian surnames based on the given name "Giovanni".[32]

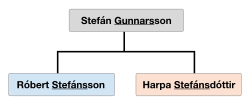

Patronymic surnames can be a parent's name without modification (Ali Mohamed is Mohamed's son), preceded by a modifying word/character (bin Abdulaziz, Mac Donald), or modified by affixes (Stefanović, Petrov, Jones, Olsen, López, Price, Dēmētrópoulos, Fitzgerald). There is a wide range of family name affixes with a patronymic function.

Patronymic surnames can be actively changing with each generation (Senai Abraham father of Zerezghi Senai father of Afwerki Zerezghi) or derived from historical patronymics but now consistent between generations (as in Sarah Jones whose father is Benjamin Jones, and all her paternal grandfathers surnamed Jones back 200 years).

Patronymics can represent a single generation (Ali Mohamed is Mohamed's son) or multiple generations (Lemlem Mengesha Abraha is Lemlem son of Mengesha son of Abraha, his son could be Tamrat Lemlem Mengesha).

See Patronymic surname for specifics on cultural differences. See family name affixes for a list of specific prefixes and suffixes with their meanings and associated languages.

Examples[edit]

- Patronal from patronage (Hickman meaning Hick's man, where Hick is a pet form of the name Richard) or strong ties of religion Kilpatrick (follower of Patrick) or Kilbride (follower of Bridget).

- Patronymics, matronymics or ancestral, often from a person's given name. e.g., from male name: Richardson, Stephenson, Jones (Welsh for Johnson), Williams, Jackson, Wilson, Thompson, Benson, Johnson, Harris, Evans, Simpson, Willis, Fox, Davies, Reynolds, Adams, Dawson, Lewis, Rogers, Murphy, Morrow, Nicholson, Robinson, Powell, Ferguson, Davis, Edwards, Hudson, Roberts, Harrison, Watson, or female names Molson (from Moll for Mary), Madison (from Maud), Emmott (from Emma), Marriott (from Mary) or from a clan name (for those of Scottish origin, e.g., MacDonald, Forbes, Henderson, Armstrong, Grant, Cameron, Stewart, Douglas, Crawford, Campbell, Hunter) with "Mac" Gaelic for son.[33]

Occupational surnames [edit]

Occupational names include Smith (for a smith), Miller (for a miller), Farmer (for tax farmers or sometimes farmers), Thatcher (for a thatcher), Shepherd (for a shepherd), Potter (for a potter), and so on, as well as non-English ones, such as the German Eisenhauer (iron hewer, later Anglicized in America as Eisenhower) or Schneider (tailor) – or, as in English, Schmidt (smith). There are also more complicated names based on occupational titles. In England it was common for servants to take a modified version of their employer's occupation or first name as their last name,[according to whom?] adding the letter s to the word, although this formation could also be a patronymic. For instance, the surname Vickers is thought to have arisen as an occupational name adopted by the servant of a vicar,[34] while Roberts could have been adopted by either the son or the servant of a man named Robert. A subset of occupational names in English are names thought to be derived from the medieval mystery plays. The participants would often play the same roles for life, passing the part down to their oldest sons. Names derived from this may include King, Lord and Virgin. The original meaning of names based on medieval occupations may no longer be obvious in modern English (so the surnames Cooper, Chandler, and Cutler come from the occupations of making barrels, candles, and cutlery, respectively).

Examples[edit]

Archer, Bailey, Bailhache, Baker, Barbieri, Brewer, Butcher, Carpenter, Carter, Chandler, Clark or Clarke, Collier, Cooper, Cook or Cooke, Dempster, Dyer, Fabbri, Farmer, Faulkner, Ferrari, Ferrero, Fisher, Fisichella, Fletcher, Fowler, Fuller, Gardener, Glover, Hayward, Hawkins, Head, Hunt or Hunter, Judge, Knight, Mason, Miller, Mower, Page, Palmer, Parker, Porter, Potter, Reeve or Reeves, Sawyer, Shoemaker, Slater, Smith, Stringer, Taylor, Thacker or Thatcher, Turner, Walker, Weaver, Woodman and Wright (or variations such as Cartwright and Wainwright).

Toponymic surnames[edit]

Location (toponymic, habitation) names derive from the inhabited location associated with the person given that name. Such locations can be any type of settlement, such as homesteads, farms, enclosures, villages, hamlets, strongholds, or cottages. One element of a habitation name may describe the type of settlement. Examples of Old English elements are frequently found in the second element of habitational names. The habitative elements in such names can differ in meaning, according to different periods, different locations, or with being used with certain other elements. For example, the Old English element tūn may have originally meant "enclosure" in one name, but can have meant "farmstead", "village", "manor", or "estate" in other names.

Location names, or habitation names, may be as generic as "Monte" (Portuguese for "mountain"), "Górski" (Polish for "hill"), or "Pitt" (variant of "pit"), but may also refer to specific locations. "Washington", for instance, is thought to mean "the homestead of the family of Wassa",[35] while "Lucci" means "resident of Lucca".[32] Although some surnames, such as "London", "Lisboa", or "Białystok" are derived from large cities, more people reflect the names of smaller communities, as in Ó Creachmhaoil, derived from a village in County Galway. This is thought to be due to the tendency in Europe during the Middle Ages for migration to chiefly be from smaller communities to the cities and the need for new arrivals to choose a defining surname.[35][36]

In Portuguese-speaking countries, it is uncommon, but not unprecedented, to find surnames derived from names of countries, such as Portugal, França, Brasil, Holanda. Surnames derived from country names are also found in English, such as "England", "Wales", "Spain".

Many Japanese surnames derive from geographical features; for example, Ishikawa (石川) means "stone river", Yamamoto (山本) means "the base of the mountain", and Inoue (井上) means "above the well".

Arabic names sometimes contain surnames that denote the city of origin. For example, in cases of Saddam Hussein al Tikriti,[37] meaning Saddam Hussein originated from Tikrit, a city in Iraq. This component of the name is called a nisbah.

Examples[edit]

- Estate names For those descended from land-owners, the name of their holdings, castle, manor or estate, e.g. Ernle, Windsor, Staunton

- Habitation (place) names e.g., Burton, Flint, Hamilton, London, Laughton, Leighton, Murray, Sutton, Tremblay

- Topographic names (geographical features) e.g., Bridge or Bridges, Brook or Brooks, Bush, Camp, Hill, Lake, Lee or Leigh, Wood, Grove, Holmes, Forest, Underwood, Hall, Field, Stone, Morley, Moore, Perry

Cognominal surnames[edit]

This is the broadest class of surnames, encompassing many types of origin. These include names based on appearance such as "Schwartzkopf", "Short", and possibly "Caesar",[32] and names based on temperament and personality such as "Daft", "Gutman", and "Maiden", which, according to a number of sources, was an English nickname meaning "effeminate".[32][35]

Examples[edit]

- Physical attributes e.g., Short, Brown, Black, Whitehead, Young, Long, White, Stark, Fair

- Temperament and personality e.g. Daft, Gutman, Maiden, Smart, Happy

Acquired and ornamental surnames[edit]

Ornamental surnames are made up of names, not specific to any attribute (place, parentage, occupation, caste) of the first person to acquire the name, and stem from the middle class's desire for their own hereditary names like the nobles. They were generally acquired later in history and generally when those without surnames needed them. In 1526, King Frederik I of Denmark-Norway ordered that noble families must take up fixed surnames, and many of them took as their name some element of their coat of arms; for example, the Rosenkrantz (“rose wreath”) family took their surname from a wreath of roses comprising the torse of their arms,[38] and the Gyldenstierne (“golden star”) family took theirs from a 7-pointed gold star on their shield.[39] Subsequently, many middle-class Scandinavian families desired names similar to those of the nobles and adopted “ornamental” surnames as well. Most other naming traditions refer to them as "acquired". They might be given to people newly immigrated, conquered, or converted, as well as those with unknown parentage, formerly enslaved, or from parentage without a surname tradition.[40][41]

Ornamental surnames are more common in communities that adopted (or were forced to adopt) surnames in the 18th and 19th centuries.[36]

They occur commonly in Scandinavia, among Sinti and Roma and Jews in Germany and Austria.[32] Examples include "Steinbach" ("derived from a place called Steinbach"), "Rosenberg" ("rose mountain"), and "Winterstein" (derived from a place called Winterstein). Forced adoption in the 19th century is the source of German, Polish and even Italian ornamental surnames for Latvians such as "Rozentāls (Rosental)" ("rose valley"), "Eizenbaums (Eisenbaum") ("steel wood"), "Freibergs (Freiberg)" ("free mountain").

In some cases, such as Chinese Indonesians and Chinese Thais, certain ethnic groups are subject to political pressure to change their surnames, in which case surnames can lose their family-name meaning. For instance, Indonesian business tycoon Liem Swie Liong (林绍良) "indonesianised" his name to Sudono Salim. In this case, "Liem" (林) was rendered by "Salim", a name of Arabic origin, while "Sudono", a Javanese name with the honorific prefix "su-" (of Sanskrit origin), was supposed to be a rendering of "Swie Liong".

During the era of the Trans-Atlantic slave trade many Africans lost their native names and were forced by their owners to take the owners' surnames and any given name the "owner" or slave master desired. In the Americas, the family names of many African-Americans have their origins in slavery (i.e. slave name).[citation needed] Many freed slaves either created family names themselves or adopted the name of their former master.[citation needed]

In regions with a strong religious influence, newly acquired names were often given by the religious leaders as part of naming ceremonies. The religion dictated the type of surname but these are traditionally surnames associated with the religion. Islamic names often follow the Arabic patronymic naming conventions but include names like Mohamed or ibn Abihi, "son of his father". Catholic names may have been influenced by the Saint on whose feast day the person was christened, for instance Toussaint and De Los Santos may have been christened on All Saints' Day.

As Native Peoples of the Americas were assimilated by the conquering countries, they were often converted to the dominant religion, being christened with associated names (ie. de la Cruz). Others maintained a historical name, title, or byname of an ancestor translated into the new language (ie. RunningWolf). Yet others were simply given "appropriate sounding" invented names (as Markishtum for members of the Makah tribe).

Another category of acquired names is foundlings names. Historically, children born to unwed parents or extremely poor parents would be abandoned in a public place or anonymously placed in a foundling wheel. Such abandoned children might be claimed and named by religious figures, the community leaders, or adoptive parents. Some such children were given surnames that reflected their condition, like (Italian) Esposito, Innocenti, Della Casagrande, Trovato, Abbandonata, or (Dutch) Vondeling, Verlaeten, Bijstand. Other children were named for the street/place they were found (Union, Liquorpond (street), di Palermo, Baan, Bijdam, van den Eyngel (shop name), van der Stoep, von Trapp), the date they were found (Monday, Septembre, Spring, di Gennaio), or festival/feast day they found or christened (Easter, SanJosé). Some foundlings were given the name of whoever found them.[42][43][44]

Gender-specific versions of surname[edit]

In some cultures and languages, especially the Baltic languages (Latvian and Lithuanian), and most of the Slavic languages (such as Bulgarian, Russian, Slovak, Czech, etc.) and some other nations – Greece and Iceland – surnames change form depending on the gender of the bearer.

Some Slavic cultures originally distinguished the surnames of married and unmarried women by different suffixes, but this distinction is no longer widely observed. In Slavic languages, substantivized adjective surnames have commonly symmetrical adjective variants for males and females (Podwiński/Podwińska in Polish, Nový/Nová in Czech or Slovak, etc.). In the case of nominative and quasi-nominative surnames, the female variant is derived from the male variant by a possessive suffix (Novák/Nováková, Hromada/Hromadová). In Czech and Slovak, the pure possessive would be Novákova, Hromadova, but the surname evolved to a more adjectivized form Nováková, Hromadová, to suppress the historical possessivity. Some rare types of surnames are universal and gender-neutral: examples in Czech are Janů, Martinů, Fojtů, Kovářů. These are the archaic form of the possessive, related to the plural name of the family. Such rare surnames are also often used for transgender persons during transition because most common surnames are gender-specific. Some Czech dialects (Southwest-Bohemian) use the form "Novákojc" as informal for both genders. In the culture of the Sorbs (a.k.a. Wends or Lusatians), Sorbian used different female forms for unmarried daughters (Jordanojc, Nowcyc, Kubašec, Markulic), and for wives (Nowakowa, Budarka, Nowcyna, Markulina). In Polish, typical surnames for unmarried women ended -ówna, -anka, or -ianka, while the surnames of married women used the possessive suffixes -ina or -owa. The informal dialectal female form in Polish and Czech dialects was also -ka (Pawlaczka, Kubeška). With the exception of the -ski/-ska suffix, most feminine forms of surnames are seldom observed in Polish. In Czech, a trend to use male surnames for women is popular among cosmopolitans or celebrities, but is often criticized from patriotic views and can be seen as ridiculous and as degradation and disruption of Czech grammar. Adaptation of surnames of foreign women by the suffix "-ová" is currently a hot linguistic and political question in Czechia; it is massively advocated as well as criticized and opposed.

Generally, inflected languages use names and surnames as living words, not as static identifiers. Thus, the pair or the family can be named by a plural form which can differ from the singular male and female form. For instance, when the male form is Novák and the female form Nováková, the family name is Novákovi in Czech and Novákovci in Slovak. When the male form is Hrubý and the female form is Hrubá, the plural family name is Hrubí (or "rodina Hrubých").

In Greece, if a man called Papadopoulos has a daughter, she will likely be named Papadopoulou (if the couple has decided their offspring will take his surname), the genitive form, as if the daughter is "of" a man named Papadopoulos.

In Lithuania, if the husband is named Vilkas, his wife will be named Vilkienė and his unmarried daughter will be named Vilkaitė. Male surnames have suffixes -as, -is, -ius, or -us, unmarried girl surnames aitė, -ytė, -iūtė or -utė, wife surnames -ienė. These suffixes are also used for foreign names, exclusively for grammar; the surname of the present Archbishop of Canterbury, for example, becomes Velbis in Lithuanian, while his wife is Velbienė, and his unmarried daughter, Velbaitė.

Latvian, like Lithuanian, use strictly feminized surnames for women, even in the case of foreign names. The function of the suffix is purely grammar. Male surnames ending -e or -a need not be modified for women. An exception is 1) the female surnames which correspond to nouns in the sixth declension with the ending "-s" – "Iron", ("iron"), "rock", 2) as well as surnames of both genders, which are written in the same nominative case because corresponds to nouns in the third declension ending in "-us" "Grigus", "Markus"; 3) surnames based on an adjective have indefinite suffixes typical of adjectives "-s, -a" ("Stalts", "Stalta") or the specified endings "-ais, -ā" ("Čaklais", "Čaklā") ("diligent").

In Iceland, surnames have a gender-specific suffix (-dóttir = daughter, -son = son).

Finnish used gender-specific suffixes up to 1929 when the Marriage Act forced women to use the husband's form of the surname. In 1985, this clause was removed from the act.

Other[edit]

The meanings of some names are unknown or unclear. The most common European name in this category may be the English (Irish derivative) name Ryan, which means 'little king' in Irish.[35][34] Also, Celtic origin of the name Arthur, meaning 'bear'. Other surnames may have arisen from more than one source: the name De Luca, for instance, likely arose either in or near Lucania or in the family of someone named Lucas or Lucius;[32] in some instances, however, the name may have arisen from Lucca, with the spelling and pronunciation changing over time and with emigration.[32] The same name may appear in different cultures by coincidence or romanization; the surname Lee is used in English culture, but is also a romanization of the Chinese surname Li.[34] Surname origins have been the subject of much folk etymology.

In French Canada until the 19th century, several families adopted surnames that followed the family name in order to distinguish the various branches of a large family. Such a surname was preceded by the word dit ("so-called," lit. "said") and was known as a nom-dit ("said-name"). (Compare with some Roman naming conventions.) While this tradition is no longer in use, in many cases the nom-dit has come to replace the original family name. Thus the Bourbeau family has split into Bourbeau dit Verville, Bourbeau dit Lacourse, and Bourbeau dit Beauchesne. In many cases, Verville, Lacourse, or Beauchesne has become the new family name. Likewise, the Rivard family has split into the Rivard dit Lavigne, Rivard dit Loranger and Rivard dit Lanoie. The origin of the nom-dit can vary. Often it denoted a geographical trait of the area where that branch of the family lived: Verville lived towards the city, Beauchesne lived near an oak tree, Larivière near a river, etc. Some of the oldest noms-dits are derived from the war name of a settler who served in the army or militia: Tranchemontagne ("mountain slasher"), Jolicœur ("braveheart"). Others denote a personal trait: Lacourse might have been a fast runner, Legrand was probably tall, etc. Similar in German it is with genannt – "Vietinghoff genannt Scheel".

Order of names[edit]

In many cultures (particularly in European and European-influenced cultures in the Americas, Oceania, etc., as well as West Asia/North Africa, South Asia, and most Sub-Saharan African cultures), the surname or family name ("last name") is placed after the personal, forename (in Europe) or given name ("first name"). In other cultures the surname is placed first, followed by the given name or names. The latter is often called the Eastern naming order because Europeans are most familiar with the examples from the East Asian cultural sphere, specifically, Greater China, Korea (the Republic of Korea and the Democratic People's Republic of Korea), Japan, and Vietnam. This is also the case in Cambodia. The Telugu people of south India also place surname before personal name. There are some parts of Europe, in particular Hungary, Bavaria in Germany, and the Samis in Europe, that in some instances also follow the Eastern order.[citation needed]

Since family names are normally written last in European societies, the terms last name or surname are commonly used for the family name, while in Japan (with vertical writing) the family name may be referred to as "upper name" (ue-no-namae (上の名前)).

When people from areas using Eastern naming order write their personal name in the Latin alphabet, it is common to reverse the order of the given and family names for the convenience of Westerners, so that they know which name is the family name for official/formal purposes. Reversing the order of names for the same reason is also customary for the Baltic Finnic peoples and the Hungarians, but other Uralic peoples traditionally did not have surnames, perhaps because of the clan structure of their societies. The Samis, depending on the circumstances of their names, either saw no change or did see a transformation of their name. For example: Sire in some cases became Siri,[45] and Hætta Jáhkoš Ásslat became Aslak Jacobsen Hætta – as was the norm. Recently, integration into the EU and increased communications with foreigners prompted many Samis to reverse the order of their full name to given name followed by surname, to avoid their given name being mistaken for and used as a surname.[citation needed]

Indian surnames may often denote village, profession, and/or caste and are invariably mentioned along with the personal/first names. However, hereditary last names are not universal. In Telugu-speaking families in south India, surname is placed before personal / first name and in most cases it is only shown as an initial (for example 'S.' for Suryapeth).[46]

In English and other languages like Spanish—although the usual order of names is "first middle last"—for the purpose of cataloging in libraries and in citing the names of authors in scholarly papers, the order is changed to "last, first middle," with the last and first names separated by a comma, and items are alphabetized by the last name.[47][48] In France, Italy, Spain, Belgium and Latin America, administrative usage is to put the surname before the first on official documents.[citation needed]

Compound surnames[edit]

While in many countries surnames are usually one word, in others a surname may contain two words or more, as described below.

English compound surnames[edit]

Compound surnames in English and several other European cultures feature two (or occasionally more) words, often joined by a hyphen or hyphens. However, it is not unusual for compound surnames to be composed of separate words not linked by a hyphen, for example Iain Duncan Smith, a former leader of the British Conservative Party, whose surname is "Duncan Smith".

Surname affixes[edit]

Many surnames include prefixes that may or may not be separated by a space or punctuation from the main part of the surname. These are usually not considered true compound names, rather single surnames are made up of more than one word. These prefixes often give hints about the type or origin of the surname (patronymic, toponymic, notable lineage) and include words that mean from [a place or lineage], and son of/daughter of/child of.

The common Celtic prefixes "Ó" or "Ua" (descendant of) and "Mac" or "Mag" (son of) can be spelled with the prefix as a separate word, yielding "Ó Briain" or "Mac Millan" as well as the anglicized "O'Brien" and "MacMillan" or "Macmillan". Other Irish prefixes include Ní, Nic (daughter of the son of), Mhic, and Uí (wife of the son of).

A surname with the prefix "Fitz" can be spelled with the prefix as a separate word, as in "Fitz William", as well as "FitzWilliam" or "Fitzwilliam" (like, for example, Robert FitzRoy). Note that "Fitz" comes from French (fils) thus making these surnames a form of patronymic.

See other articles: Irish surname additives, Spanish nominal conjunctions, Von, Van, List of family name affixes, Patronymic surname, and Toponymic surname

Chinese compound surnames[edit]

Some Chinese surnames use more than one character.

Spanish-speaking world[edit]

In Spain and in most Spanish-speaking countries, the custom is for people to have two surnames, with the first surname coming from the father and the second from the mother; the opposite order is now legally allowed in Spain but still unusual. In informal situations typically only the first one is used, although both are needed for legal purposes. A child's first surname will usually be their father's first surname, while the child's second surname will usually be their mother's first surname. For example, if José García Torres and María Acosta Gómez had a child named Pablo, then his full name would be Pablo García Acosta. One family member's relationship to another can often be identified by the various combinations and permutations of surnames.

| José García Torres | María Acosta Gómez | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pablo García Acosta | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

In some instances, when an individual's first surname is very common, such as for example in José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero, the second surname tends to gain preeminence over the first one in informal use. Rodriguez Zapatero, therefore is more often called just Zapatero and almost never Rodriguez only; in other cases, such as in writer Mario Vargas Llosa, a person becomes usually called by both surnames. This changes from person to person and stems merely from habit.

In Spain, feminist activism pushed for a law approved in 1999 that allows an adult to change the order of his/her family names,[49] and parents can also change the order of their children's family names if they (and the child, if over 12) agree, although this order must be the same for all their children.[50][51]

In Spain, especially Catalonia, the paternal and maternal surnames are often combined using the conjunction y ("and" in Spanish) or i ("and" in Catalan), see for example the economist Xavier Sala-i-Martin or painter Salvador Dalí i Domènech.

In Spain, a woman does not generally change her legal surname when she marries. In some Spanish-speaking countries in Latin America, a woman may, on her marriage, drop her mother's surname and add her husband's surname to her father's surname using the preposition de ("of"), del ("of the", when the following word is masculine) or de la ("of the", when the following word is feminine). For example, if "Clara Reyes Alba" were to marry "Alberto Gómez Rodríguez", the wife could use "Clara Reyes de Gómez" as her name (or "Clara Reyes Gómez", or, rarely, "Clara Gómez Reyes". She can be addressed as Sra. de Gómez corresponding to "Mrs Gómez"). Feminist activists have criticized this custom[when?] as they consider it sexist.[52][53] In some countries, this form may be mainly social and not an official name change, i.e. her name would still legally be her birth name. This custom, begun in medieval times, is decaying and only has legal validity[citation needed] in Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Guatemala, Nicaragua, Honduras, Peru, Panama, and to a certain extent in Mexico (where it is optional but becoming obsolete), but is frowned upon by people in Spain, Cuba, and elsewhere. In Peru and the Dominican Republic, women normally conserve all family names after getting married. For example, if Rosa María Pérez Martínez marries Juan Martín De la Cruz Gómez, she will be called Rosa María Pérez Martínez de De la Cruz, and if the husband dies, she will be called Rosa María Pérez Martínez Vda. de De la Cruz (Vda. being the abbreviation for viuda, "widow" in Spanish). The law in Peru changed some years ago, and all married women can keep their maiden last name if they wish with no alteration.

Historically, sometimes a father transmitted his combined family names, thus creating a new one e.g., the paternal surname of the son of Javier (given name) Reyes (paternal family name) de la Barrera (maternal surname) may have become the new paternal surname Reyes de la Barrera. For example, Uruguayan politician Guido Manini Rios has inherited a compound surname constructed from the patrilineal and matrilineal surnames of a recent ancestor. De is also the nobiliary particle used with Spanish surnames. This can not be chosen by the person, as it is part of the surname, for example, "Puente" and "Del Puente" are not the same surname.

Sometimes, for single mothers or when the father would or could not recognize the child, the mother's surname has been used twice: for example, "Ana Reyes Reyes". In Spain, however, children with just one parent receive both surnames of that parent, although the order may also be changed. In 1973 in Chile, the law was changed to avoid stigmatizing illegitimate children with the maternal surname repeated.

Some Hispanic people, after leaving their country, drop their maternal surname, even if not formally, so as to better fit into the non-Hispanic society they live or work in. Similarly, foreigners with just one surname may be asked to provide a second surname on official documents in Spanish-speaking countries. When none (such as the mother's maiden name) is provided, the last name may simply be repeated.

A new trend in the United States for Hispanics is to hyphenate their father's and mother's last names. This is done because American-born English-speakers are not aware of the Hispanic custom of using two last names and thus mistake the first last name of the individual for a middle name. In doing so they would, for example, mistakenly refer to Esteban Álvarez Cobos as Esteban A. Cobos. Such confusion can be particularly troublesome in official matters. To avoid such mistakes, Esteban Álvarez Cobos, would become Esteban Álvarez-Cobos, to clarify that both are last names.

In some churches, such as the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, where the family structure is emphasized, as well as a legal marriage, the wife is referred to as "hermana" [sister] plus the surname of her husband. And most records of the church follow that structure as well.

Informal traditional names[edit]

In many places, such as villages in Catalonia, Galicia, and Asturias and in Cuba, people are often informally known by the name of their dwelling or collective family nickname rather than by their surnames. For example, Remei Pujol i Serra who lives at Ca l'Elvira would be referred to as "Remei de Ca l'Elvira"; and Adela Barreira López who is part of the "Provisores" family would be known as "Adela dos Provisores".

Also in many places, such as Cantabria, the family's nickname is used instead of the surname: if one family is known as "Ñecos" because of an ancestor who was known as "Ñecu", they would be "José el de Ñecu" or "Ana la de Ñecu" (collective: the Ñeco's). Some common nicknames are "Rubiu" (blonde or ginger hair), "Roju" (reddish, as referred to ginger hair), "Chiqui" (small), "Jinchu" (big), and a bunch of names about certain characteristics, family relationship or geographical origin (pasiegu, masoniegu, sobanu, llebaniegu, tresmeranu, pejinu, naveru, merachu, tresneru, troule, mallavia, marotias, llamoso, lipa, ñecu, tarugu, trapajeru, lichón, andarível).

Compound surnames[edit]

Beyond the seemingly "compound" surname system in the Spanish-speaking world, there are also true compound surnames. These true compound surnames are passed on and inherited as compounds. For instance, former Chairman of the Supreme Military Junta of Ecuador, General Luis Telmo Paz y Miño Estrella, has Luis as his first given name, Telmo as his middle name, the true compound surname Paz y Miño as his first (i.e. paternal) surname, and Estrella as his second (i.e. maternal) surname. Luis Telmo Paz y Miño Estrella is also known more casually as Luis Paz y Miño, Telmo Paz y Miño, or Luis Telmo Paz y Miño. He would never be regarded as Luis Estrella, Telmo Estrella, or Luis Telmo Estrella, nor as Luis Paz, Telmo Paz, or Luis Telmo Paz. This is because "Paz" alone is not his surname (although other people use the "Paz" surname on its own).[4] In this case, Paz y Miño is in fact the paternal surname, being a true compound surname. His children, therefore, would inherit the compound surname "Paz y Miño" as their paternal surname, while Estrella would be lost, since the mother's paternal surname becomes the children's second surname (as their own maternal surname). "Paz" alone would not be passed on, nor would "Miño" alone.

To avoid ambiguity, one might often informally see these true compound surnames hyphenated, for instance, as Paz-y-Miño. This is true especially in the English-speaking world, but also sometimes even in the Hispanic world, since many Hispanics are unfamiliar with this and other compound surnames, "Paz y Miño" might be inadvertently mistaken as "Paz" for the paternal surname and "Miño" for the maternal surname. Although Miño did start off as the maternal surname in this compound surname, it was many generations ago, around five centuries, that it became compounded, and henceforth inherited and passed on as a compound.

Other surnames which started off as compounds of two or more surnames, but which merged into one single word, also exist. An example would be the surname Pazmiño, whose members are related to the Paz y Miño, as both descend from the "Paz Miño" family of five centuries ago.

Álava, Spain is known for its incidence of true compound surnames, characterized for having the first portion of the surname as a patronymic, normally a Spanish patronymic or more unusually a Basque patronymic, followed by the preposition "de", with the second part of the surname being a placename from Álava.

Portuguese-speaking countries[edit]

In the case of Portuguese naming customs, the main surname (the one used in alpha sorting, indexing, abbreviations, and greetings), appears last.

Each person usually has two family names: though the law specifies no order, the first one is usually the maternal family name, whereas the last one is commonly the paternal family name. In Portugal, a person's full name has a minimum legal length of two names (one given name and one family name from either parent) and a maximum of six names (two first names and four surnames – he or she may have up to four surnames in any order desired picked up from the total of his/her parents and grandparents' surnames). The use of any surname outside this lot, or of more than six names, is legally possible, but it requires dealing with bureaucracy. Parents or the person him/herself must explain the claims they have to bear that surname (a family nickname, a rare surname lost in past generations, or any other reason one may find suitable). In Brazil, there is no limit of surnames used.

In general, the traditions followed in countries like Brazil, Portugal and Angola are somewhat different from the ones in Spain. In the Spanish tradition, usually, the father's surname comes first, followed by the mother's surname, whereas in Portuguese-speaking countries the father's name is the last, mother's coming first. A woman may adopt her husband's surname(s), but nevertheless, she usually keeps her birth name or at least the last one. Since 1977 in Portugal and 2012 in Brazil, a husband can also adopt his wife's surname. When this happens, usually both spouses change their name after marriage.

The custom of a woman changing her name upon marriage is recent. It spread in the late 19th century in the upper classes, under French influence, and in the 20th century, particularly during the 1930s and 1940, it became socially almost obligatory. Nowadays, fewer women adopt, even officially, their husbands' names, and among those who do so officially, it is quite common not to use it either in their professional or informal life.[citation needed]

The children usually bear only the last surnames of the parents (i.e., the paternal surname of each of their parents). For example, Carlos da Silva Gonçalves and Ana Luísa de Albuquerque Pereira (Gonçalves) (in case she adopted her husband's name after marriage) would have a child named Lucas Pereira Gonçalves. However, the child may have any other combination of the parents' surnames, according to euphony, social significance, or other reasons. For example, is not uncommon for the firstborn male to be given the father's full name followed by "Júnior" or "Filho" (son), and the next generation's firstborn male to be given the grandfather's name followed by "Neto" (grandson). Hence Carlos da Silva Gonçalves might choose to name his first born son Carlos da Silva Gonçalves Júnior, who in turn might name his first born son Carlos da Silva Gonçalves Neto, in which case none of the mother's family names are passed on.

| Carlos da Silva Gonçalves | Ana Luísa de Albuquerque Pereira | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lucas Pereira Gonçalves | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

In ancient times a patronymic was commonly used – surnames like Gonçalves ("son of Gonçalo"), Fernandes ("son of Fernando"), Nunes ("son of Nuno"), Soares ("son of Soeiro"), Sanches ("son of Sancho"), Henriques ("son of Henrique"), Rodrigues ("son of Rodrigo") which along with many others are still in regular use as very prevalent family names.

In Medieval times, Portuguese nobility started to use one of their estates' names or the name of the town or village they ruled as their surname, just after their patronymic. Soeiro Mendes da Maia bore a name "Soeiro", a patronymic "Mendes" ("son of Hermenegildo – shortened to Mendo") and the name of the town he ruled "Maia". He was often referred to in 12th-century documents as "Soeiro Mendes, senhor da Maia", Soeiro Mendes, lord of Maia. Noblewomen also bore patronymics and surnames in the same manner and never bore their husband's surnames. First-born males bore their father's surname, other children bore either both or only one of them at their will.

Only during the Early Modern Age, lower-class males started to use at least one surname; married lower-class women usually took up their spouse's surname, since they rarely ever used one beforehand. After the 1755 Lisbon earthquake, Portuguese authorities realized the benefits of enforcing the use and registry of surnames. Henceforth, they became mandatory, although the rules for their use were very liberal.

Until the end of the 19th century, it was common for women, especially those from a very poor background, not to have a surname and so to be known only by their first names. A woman would then adopt her husband's full surname after marriage. With the advent of republicanism in Brazil and Portugal, along with the institution of civil registries, all children now have surnames. During the mid-20th century, under French influence and among upper classes, women started to take up their husbands' surname(s). From the 1960s onwards, this usage spread to the common people, again under French influence, this time, however, due to the forceful legal adoption of their husbands' surname which was imposed onto Portuguese immigrant women in France.

From the 1974 Carnation Revolution onwards the adoption of their husbands' surname(s) receded again, and today both the adoption and non-adoption occur, with non-adoption being chosen in the majority of cases in recent years (60%).[54] Also, it is legally possible for the husband to adopt his wife's surname(s), but this practice is rare.

Culture and prevalence[edit]

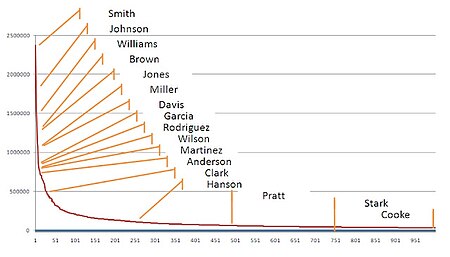

In the United States, 1,712 surnames cover 50% of the population, and about 1% of the population has the surname Smith,[55] which is also the most frequent English name and an occupational name ("metal worker"), a contraction, for instance, of blacksmith or other metalsmiths. Several American surnames are a result of corruption or phonetic misappropriations of European surnames, perhaps as a result of the registration process at the immigration entry points. Spellings and pronunciations of names remained fluid in the United States until the Social Security System enforced standardization.

Approximately 70% of Canadians have surnames that are of English, Irish, French, or Scottish derivation.

According to some estimates, 85% of China's population shares just 100 surnames. The names Wang (王), Zhang (张), and Li (李) are the most frequent.[56]

See also[edit]

- Genealogy

- Generation name

- Given name

- Legal name

- List of family name affixes

- Lists of most common surnames

- Maiden and married names

- Matriname

- Name blending

- Name change

- Names ending with -ington

- Naming law

- Nobiliary particle

- One-name study

- Patronymic surname

- Personal name

- Skin name

- Surname extinction

- Surname law

- Surname map

- Surnames by country

- T–V distinction

- Tussenvoegsel

References[edit]

- ↑ "surname". OxfordDictionaries.com. Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- ↑ "BBC - Family History - What's in a Name? Your Link to the Past". www.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 21 September 2020.

- ↑ Koon, Wee Kek (18 November 2016). "The complex origins of Chinese names demystified". Post Magazine.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Kelly, 99 W Va L Rev at 10; see id. at 10 n 25 (The custom of taking the father's surname assumes that the child is born to parents in a "state-sanctioned marriage". The custom is different for children born to unmarried parents.). Cited in Doherty v. Wizner, Oregon Court of Appeals (2005)

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Doll, Cynthia Blevins (1992). "Harmonizing Filial and Parental Rights in Names: Progress, Pitfalls, and Constitutional Problems". Howard Law Journal. 35. Howard University School of Law. p. 227. ISSN 0018-6813. Note: content available by subscription only. The first page of content is available via Google Scholar.

- ↑ Seng, Serena (15 September 2008). "The Origin of Chinese Surnames". In Powell, Kimberly. About Genealogy. The New York Times Company. Search this book on

- ↑ Danesi, Marcel (2007). The Quest for Meaning. University of Toronto Press. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-8020-9514-5. Retrieved 21 September 2008. Search this book on

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 linguistics.berkeley.edu (2004). http://www.linguistics.berkeley.edu/~rosemary/55-2004-names.pdf, "Naming practices". A PDF file with a section on "Chinese naming practices (Mak et al., 2003)". Archived at WebCite https://www.webcitation.org/5xd5YvhE3?url=http://www.linguistics.berkeley.edu/%7Erosemary/55-2004-names.pdf on 1Apr11.

- ↑ Zhimin, An (1988). "Archaeological Research on Neolithic China". Current Anthropology. 29 (5): 753–759 [755, 758]. doi:10.1086/203698. JSTOR 2743616. Unknown parameter

|s2cid=ignored (help) (The first few sentences are accessible online via JSTOR at https://www.jstor.org/stable/2743616, i.e., p.753.) - ↑ Gill, N.S. (25 January 2008). "Ancient Names – Greek and Roman Names". In Gill, N.S. About Ancient / Classical History. The New York Times Company. Search this book on

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Benet Salway, "What's in a Name? A Survey of Roman Onomastic Practice from c. 700 B.C. to A.D. 700", in Journal of Roman Studies, vol. 84, pp. 124–145 (1994).

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Chavez, Berret (9 November 2006). "Personal Names of the Aristocracy in the Roman Empire During the Later Byzantine Era". Official Web Page of the Laurel Sovereign of Arms for the Society for Creative Anachronism. Society for Creative Anachronism. Retrieved 21 September 2008.

- ↑ https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/familyhistory/get_started/surnames_01.shtml#:~:text=Over%20time%20many%20names%20became,and%20to%20get%20passed%20on.

- ↑ https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/familyhistory/get_started/surnames_01.shtml#:~:text=Over%20time%20many%20names%20became,and%20to%20get%20passed%20on.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 "Most common surnames in Britain and Ireland revealed". BBC. 17 November 2016.

- ↑ Hanks, Patrick; Coates, Richard; McClure, Peter (17 November 2016). The Oxford Dictionary of Family Names in Britain and Ireland. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780199677764.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-967776-4. Search this book on

- ↑ Nagata, Mary Louise. "Names and Name Changing in Early Modern Kyoto, Japan." International Review of Social History 07/2002; 47(02):243 – 259. P. 246.

- ↑ Richard H. Thornton, The Controversy Over Children's Surnames: Familial Autonomy, Equal Protection, and the Child's Best Interests, 1979 Utah L Rev 303.

- ↑ Joanna Grossman, Whose Surname Should a Child Have, FindLaw's Writ column (12 August 2003), (last visited 7 December 2006).

- ↑ "American Women, Changing Their Names", National Public Radio. Retrieved 10 April 2013.

- ↑ Daniella Miletic (20 July 2012) Most women say 'I do' to husband's name. The Age.

- ↑ UN Convention, 1979. "Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women". Archived at WebCite on 1 April 2011.

- ↑ Risling, Greg (12 January 2007). "Man files lawsuit to take wife's name". The Boston Globe (Boston.com). Los Angeles. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 27 January 2007. Retrieved 22 September 2008.

Because of Buday's case, a California state lawmaker has introduced a bill to put a space on the marriage license for either spouse to change names.

Unknown parameter|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ Québec newlywed furious she can't take her husband's name Archived 2 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine, by Marianne White, CanWest News Service, 8 August 2007 . Retrieved 3 November 2013.

- ↑ "Civil Code".

- ↑ "Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women". Hrweb.org. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ↑ Burghartz v. Switzerland, no. 16213/90, 22 February 1994.

- ↑ Losonci Rose and Rose v. Switzerland, no. 664/06, 9 November 2010.

- ↑ Ünal Tekeli v Turkey, no. 29865/96, 16 November 2004.

- ↑ "European Gender Equality Law Review – No. 1/2012" (PDF). Ec.europa.eu. p. 17. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ↑ "Novela zákona o matrikách, jménech a příijmeni". Retrieved 3 April 2022.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 32.3 32.4 32.5 32.6 32.7 Hanks, Patrick and Hodges, Flavia. A Dictionary of Surnames. Oxford University Press, 1989. ISBN 0-19-211592-8 Search this book on

..

..

- ↑ Katherine M. Spadaro, Katie Graham (2001) Colloquial Scottish Gaelic: the complete course for beginners p.16. Routledge, 2001

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 Reaney, P.H., and Wilson, R.M. A Dictionary of English Surnames. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997. Rev. 3rd ed. ISBN 0-19-860092-5 Search this book on

..

..

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 35.3 Cottle, Basil. Penguin Dictionary of Surnames. Baltimore, MD: Penguin Books, 1967. No ISBN.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Bowman, William Dodgson. The Story of Surnames. London, George Routledge & Sons, Ltd., 1932. No ISBN.

- ↑ "Saddam Hussein's top aides hanged". BBC News. 15 January 2007. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ↑ Hiort-Lorensen, H.R., and Thiset, A. (1910) Danmarks Adels Aarbog, 27th ed. Copenhagen: Vilh. Trydes Boghandel, p. 371.

- ↑ von Irgens-Bergh, G.O.A., and Bobe, L. (1926) Danmarks Adels Aarbog, 43rd ed. Copenhagen: Vilh. Trydes Boghandel, p. 3.

- ↑ "Ornamental Name". Nordic Names. Retrieved 27 July 2021.

- ↑ "The History of Last Names". Retrieved 27 July 2021.

- ↑ "Finding Foundlings: Searching for Abandoned Children in Italy". Legacy Tree Genealogists. 14 September 2017. Retrieved 27 July 2021.

- ↑ "England Regional, Ethnic, Foundling Surnames (National Institute)". FamilySearch Research Wiki. 4 September 2014. Retrieved 27 July 2021.

- ↑ "Deciphering Dutch Foundling Surnames". Dutch Ancestry Coach. Retrieved 27 July 2021.

- ↑ "Guttorm". Snl.no. 29 May 2017. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ↑ Brown, Charles Philip (1857). A Grammar of the Telugu Language. printed at the Christian Knowledge Society's Press. p. 209. Search this book on

- ↑ "Filing Rules" Archived 21 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine on the American Library Association website

- ↑ "MLA Works Cited Page: Basic Format" on the Purdue Online Writing Lab website, Purdue University

- ↑ Govan, Fiona (1 June 2017). "Spain overhauls tradition of 'sexist' double-barrelled surnames". The Local.

- ↑ Art. 55 Ley de Registro Civil – Civil Register Law (article in Spanish)

- ↑ Juan Carlos, R. (11 February 2000). "Real Decreto 193/2000, de 11 de febrero, de modificación de determinados artículos del Reglamento del Registro Civil en materia relativa al nombre y apellidos y orden de los mismos". Base de Datos de Legislación (in español). Noticias Juridicas. Retrieved 22 September 2008. Note: Google auto-translation of title into English: Royal Decree 193/2000, of 11 February, to amend certain articles of the Civil Registration Regulations in the field on the name and order.

- ↑ "Proper married name?". Spanish Dict. 9 January 2012.

- ↑ Frank, Francine; Anshen, Frank (1985). Language and the Sexes. SUNY Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-87395-882-0. Search this book on

- ↑ "Identidade, submissão ou amor? O que significa adoptar o apelido do marido". Lifestyle.publico.pt. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ↑ Genealogy Archived 12 October 2010 at the Library of Congress Web Archives, U.S. Census Bureau, Population Division (1995).

- ↑ LaFraniere S. Name Not on Our List? Change It, China Says. New York Times. 20 April 2009.

Further reading[edit]

- Blark. Gregory, et al. The Son Also Rises: Surnames and the History of Social Mobility (Princeton University Press; 2014) 384 pages; uses statistical data on family names over generations to estimate social mobility in diverse societies and historical periods.

- Bowman, William Dodgson. The Story of Surnames (London, George Routledge & Sons, Ltd., 1932)

- Cottle, Basil. Penguin Dictionary of Surnames (1967)

- Hanks, Patrick and Hodges, Flavia. A Dictionary of Surnames (Oxford University Press, 1989)

- Hanks, Patrick, Richard Coates and Peter McClure, eds. The Oxford Dictionary of Family Names in Britain and Ireland (Oxford University Press, 2016), which has a lengthy introduction with much comparative material.

- Reaney, P.H., and Wilson, R.M. A Dictionary of English Surnames (3rd ed. Oxford University Press, 1997)

External links[edit]

| Look up surname or Appendix:Names in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Comprehensive surname information and resource site

- Dictionnaire des noms de famille de France et d'ailleurs, French surname dictionary

- Family Facts Archive, Ancestry.com, including UK & US census distribution, immigration, and surname origins (Dictionary of American Family Names, Oxford University Press)

- Guild of One-Name Studies

- History of Jewish family Names

- Information on surname history and origins

- Italian Surnames, free searchable online database of Italian surnames.

- Most used names in India, world's 2nd most populated country

- Short explanation of Polish surname endings and their origin

- Summers, Neil (4 November 2006). "Welsh surnames and their meaning". Amlwch history databases. Retrieved 19 September 2008.

- Wilkinson, Hugh E. (December 2010). "Some Common English Surnames: Especially Those Derived from Personal Names" (PDF). Aoyama Keiei Ronshu. 45 (3). Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 January 2013. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help)