Theosophy and politics

Modern Theosophy and politics, according to the statements of Helena Blavatsky and Henry Olcott, are not connected between themselves in any way.[1] However, investigations of historians and religious studies scholars show that the Theosophical movement has played a significant role in consolidation of Indian nationalism.[2][3][4][5] Similar to neo-Hinduism, Theosophy had supporting promotion the nationalist ideology, and this gave Prof. Mark Bevir a reason to consider it not only as a form of "political movement", but also as an "integral part" of neo-Hinduism.[2]

Neo-Hinduism and Theosophy[edit]

Noticeable similarity between the teachings of the Theosophical Society (TS) and the movements of Ramakrishna, Sri Aurobindo, and Dayananda Sarasvati allows you to consider them, in Bevir's opinion, as variations of neo-Hinduism. He wrote that "they constitute a coherent and related set of religious ideas and movements constructed in a particular social and cultural context." In fact, these were attempts to form a "new spirituality" to decide the dilemmas associated with British colonial rule and modern scientific discoveries.[6][note 1]

After the TS founders' moving into India in 1879, educated Indians were particularly impressed that Blavatsky and Olcott began to defend their ancient religion and philosophy, contributing to the growth of people's self-consciousness against the foundations of colonial power. Ranbir Singh, the "Maharajah of Kashmir" and a "Vedanta scholar", sponsored Blavatsky and Olcott's travels in India. Sirdar Thakar Singh Sandhanwalia, "founder of the Singh Sabha," became a master ally of the Theosophists.[8][9] In 1915, Annie Besant stated that the British were the first foreigners to come to India, "with no intention of learning from her culture," but solely for the purpose of money-grubbing. They had "even conquered India" by the fraudulent ways of the tradesmen. "England," Besant said, "did not 'conquer her [India] by the sword' but by the help of her own swords, by bribery, intrigue, and most quiet diplomacy, fomenting of divisions, and playing of one party against another."[10] In her "countless speeches and lectures", Besant invariably emphasized the "wisdom and morality" of Hindu ideals, the magnificence of India's past, and encouraged Indians to restore the glory of their civilization which they lost during the period of British colonial rule.[11] Like other neo-Hinduists, the Theosophists tried to convince the Indians of the value of "their own civilization, to pride in their past, creating self-respect in the present, and self confidence in the future."[12]

Bevir noted that in India Theosophy "became an integral part of a wider movement of neo-Hinduism", which gave Indian nationalists a "legitimating ideology, a new-found confidence, and experience of organisation." He stated the Theosophists, like Dayananda Sarasvati, Swami Vivekananda, and Sri Aurobindo, "eulogised the Hindu tradition", however simultaneously calling forth to deliverance from the vestiges of the past. Theosophists and neo-Hinduists were urging nationalists to view the country as a whole, as having a common heritage and facing a set of problems requiring an all-Indian answer. They managed to make popular the belief in the "golden age" when India was free from spiritual and social problems like modern ones. They suggested that even now India continues to possess that spirituality that is not in the West and without which the West cannot do.[13]

Allan Hume as a politician[edit]

Allan Octavian Hume, a British colonial official in India[14], together with Alfred Percy Sinnett participated in a correspondence with the Theosophical mahatmas organized by Blavatsky.[15][note 2] He joined TS in 1880 and already in 1881 became the head of its section in Simla.[17] Even before the meeting with the Theosophists, Hume had the opportunity to read secret reports from many places in India (it was in 1878), which convinced him that most of the native population was unhappy with British rule and was ready to oppose the colonialists even in arms.[18] Since the opinion of the mahatmas on the situation in the country confirmed the reports of 1878, Hume concluded that they decided "to warn him of an impending catastrophe" in order that he, using his authority and connections in the British administration, help prevent this catastrophe.[19]

First of all, Hume tried to persuade Lord Ripon, the Viceroy of India, to "reform the administration of India so as to make it more responsive to the Indian people."[15] In addition, he decided to promote the idea of a pan-Indian organization, through which the native people could express their "concerns and aspirations."[20] He believed that the future organization should be called the Indian National Union. In 1885, this idea obtained support of Poona Sarvajanik Sabha as well as the "Bombay group for an all-India political conference to be held in Poona during December 1885." By visiting Madras and Calcutta, Hume persuaded local leaders to agree with his plans to create an Indian National Union. The first session of the organization was held in Bombay in December 1885, and its members "immediately" called for renaming it into Indian National Congress (INC). Hume became its general secretary.[14][21][15]

In Bevir's opinion, Hume was able to carry out his plans, largely due to the fact that he worked with people whom he repeatedly met at the annual conventions of TS. Theosophy had a "specific impact" on Indian nationalism. Hume and some Indians who obtained Western education used it for political purposes, in particular, to provide the conditions for the formation of the nationalist movement.[22] It should also be noted that no Indian could become the founder of INC and, as Gopal Krishna Gokhale wrote,

"if the founder of the Congress had not been a great Englishman and a distinguished ex-official, such was the distrust of political agitation in those days that the authorities would have at once found some way or other to suppress the movement."[23]

Annie Besant as a politician[edit]

Besant, who replaced Olcott as president in 1907, reaffirmed the role of the Theosophical Society as "a religious and cultural" organization, but not political one.[24] However, 1913 was a "turning point" in the activities of Besant herself. At the end of this year, she gave a series of lectures under the general title "Wake Up, India."[4][25] The experience of the "nationwide political agitation" acquired by her in England included public speeches, the publication of newspapers and brochures, and participation in lawsuits. In 1914, Besant started off publication of two political newspapers, a weekly The Commonwealth, and a daily New India.[4][note 3] During the year, she published in New India articles that discussed the role that INC should play. Many of the most significant publications confirming her views belonged not only to Theosophists, such as Krishna Rao and Srinivasa Aiyar, but also to other nationalists. Thus, Besant tried to impose onto INC a "more radical political programme". She required self-government for India in the near future, and she wanted INC to put forward this demand, leading a propaganda campaign using methods known to her to work in England. In her opinion, INC should have "formulate, proclaim, and promote" the views of enlightened India on all problems of public importance. She wrote that "politics should become a permanent feature of the life of the Indian people," and not a three-day event, limited by the annual session.[28][29]

In September 1916, Besant established in Madras the All-India Home Rule League which numbered a year later 27,000 members.[30][4] The Council of the League entered: A. Besant, G. Arundale[note 4], R. Aiyar, S. Aiyar, B. P. Wadia, A. Rasul, and P. Telang, "only Ramaswami Aiyar was not a Theosophist, and even he was a sympathiser."[32] Additionally, although the number of the League members was about five times the size of the Indian section of TS, the members of TS were often leading followers in the affiliates of the League, for example, in Tanjore, Srinivasa Aiyar headed the local sections of TS and the League; in Calicut, Manjeri Ramier owned an office in both organisations; 68 out of 70 people in the Bombay City section of the League were members of TS.[33] The League called its immediate task to set up campaigning among the delegates of the upcoming session of INC in order to make the politics of Home Rule its dominant one.[32]

At the end of 1916 and beginning of 1917, the League worked "vigorously" to fulfill the task set by its leadership. In June 1917, the Madras government, concerned about the activity of the nationalists, interned Besant, Arundale, and Wadia.[34] This led to a mass protest among the Indians, Besant was elected president of INC, and in September 1917, the authorities were forced to release those arrested.[35] When Besant, Arundale, and Vadia were released, they were met in Madras, Calcutta, and Benares as heroes. In December 1917, Besant presided over the session of INC.[36][note 5] Prof. Catherine Wessinger noted that Besant was "not only the first woman to be elected president of the Indian National Congress, but she was the first president to make that position into an active year-long job." Under her leadership, INC adopted, in particular, a resolution on the inadmissibility of social discrimination of untouchables.[4] Bevir claimed as follows:

"Although the All-India Home Rule League remained independent of the Society, and although Besant generally continued to deny that the Theosophical Society was in any way political, the League relied heavily on people and networks brought together by the Society. Once again, therefore, whatever the official position of the Society, and whatever Besant might have said or intended, it quite clearly played a political role within India."[24]

Politicians and Theosophy[edit]

Gandhi[edit]

In Prof. Kocku von Stuckrad's opinion, the "most prominent example" of the impact of Theosophy on Indian society is demonstrated by a biography of Mahatma Gandhi,[37] who became informed on TS in 1889 during his learning in London.[38][39] In his autobiography he wrote that, "like many other intellectuals", he realized for the first time the importance of his own culture after meeting the Theosophists. On their recommendation, he read The Key to Theosophy by Blavatsky. He wrote, "This book stimulated in me the desire to read books on Hinduism, and disabused me of the notion fostered by the missionaries that Hinduism was rife with superstition."[40]

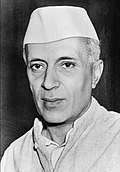

Nehru[edit]

Jawaharlal Nehru (1889–1964) was the first Prime Minister of India (from 1947 to 1964). When he was 11 years old, the Irish Theosophist Ferdinand Brooks became his home teacher, who was recommended by Annie Besant to his father. According to Nehru, Brooks taught him for three years and has extremely influenced him: for some time, Theosophy had a strongest impact on him. When he was only thirteen years old he, having received the permission of his father, joined TS. He wrote that "Mrs. Besant herself performed the ceremony of initiation." [41][42] According to Prof. Wessinger, Nehru, like many young Indians, received his first political experience as member of the All-India Home Rule League, founded by Besant.[4]

Radhakrishnan[edit]

Von Stuckrad stated that the Theosophical concept of "ancient wisdom" of humanity, based on the "Oriental spirituality", had been supporting the strengthening of anti-colonial attitudes in India. He wrote, "The wave of sympathy which embraced the Theosophists in India and Ceylon had strong political implications."[43] He cited in Cranston's book the words of Dr. Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, the philosopher and the second President of India (from 1962 to 1967), who said:

"When, with all kinds of political failures and economic breakdowns we (Indians) were suspecting the values and vitality of our culture, when everything round about us and secular education happened to discredit the value of Indian culture, the Theosophical Movement rendered great service by vindicating those values and ideas. The influence of the Theosophical Movement on general Indian society is incalculable."[44]

Deakin[edit]

Alfred Deakin (1856–1919) was an Australian politician, the Prime Minister of Australia in 1903–1904, 1905–1908, and 1909–1910. He interested in spiritualism and in works by Emanuel Swedenborg. He was during short time (1895–1896) a member of the Theosophical Society.[45][46] Nevertheless, continuing to be interested in Theosophy, attended the lectures of Olcott and Besant during their Australian tours.[47]

Lansbury[edit]

George Lansbury (1859–1940) was a British politician, the leader of the Labour Party from 1931 to 1935. By joining the Theosophical Society in 1914, he was supporting all initiatives of its president. He was the head of the British branch of the All-India Home Rule League, founded by Annie Besant.[48][49]

Accusers of the Theosophists[edit]

According to Richard Hodgson, an author of the well-known "Hodgson Report", Blavatsky's "function in India was to foster as widely as possible among the natives a disaffection towards British rule." In his article in The Age (1885), he noted that her influence has spread far beyond of the Theosophical Society. And further: "When she returned to India at the end of last [1884] year an address of sympathy was presented to her by a large body of native students of Madras, of whom only two or three were Theosophists."[50][51][note 6]

Peter Washington stated that not only Annie Besant, but other Theosophists failed to draw the border between Hinduism and Indian nationalism. The preaching of the greatness of the local religion, which was conducted by Besant, was perceived by her listeners as a call for an anti-colonial revolution, and she did not seek to refute this. He noted that the British government was not happy that an Englishwoman, a fighter for the rights of local people, invaded the electrified atmosphere of Indian politics. The anxiety of the colonial authorities was fully justified. Having familiarized themselves with Annie Besant's political credo, nationalist newspapers admired her talent as an agitator and, being flattered by her sympathy for Hinduism, called for her to stand at the head of the campaign against British rule, praising her as their savior.[53]

See also[edit]

- Buddhism and Theosophy

- Hinduism and Theosophy

- From the Caves and Jungles of Hindostan

- "What Are The Theosophists?"

- "What Is Theosophy?"

Notes[edit]

- ↑ In Vladimir Trefilov's opinion, integral yoga of Sri Aurobindo, like Blavatsky's Theosophy, is a type of the non-denominational syncretic religious philosophy.[7]

- ↑ At least ten letters from the mahatmas were addressed personally to Hume.[16]

- ↑ Besant's "editorial partner was B. P. Wadia, who did much to support the newspaper financially."[26] Bahman Pestonji Wadia (1881–1958) was an Indian Theosophist and politician, founder of the first Indian trade union.[27]

- ↑ George Sidney Arundale (1878–1945) was the third president of the Theosophical Society Adyar (from 1934 to 1945).[31]

- ↑ This session "drew a record attendance of 4,967 delegates and about 5,000 visitors including about 400 women."[4]

- ↑ Washington wrote that Blavatsky was meeted in December 1884 by native population in Madras with open arms.[52]

References[edit]

- ↑ Blavatsky 1879, p. 7; Olcott 1883, p. 14; Garrity 2014, p. 14.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Bevir 2000.

- ↑ Bevir 2003.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 Wessinger.

- ↑ Garrity 2014.

- ↑ Bevir 2000, p. 163; Bevir 2003, p. 106.

- ↑ Трефилов 2005.

- ↑ Goodrick-Clarke 2004, p. 12.

- ↑ Britannica1.

- ↑ Besant 1915, pp. lv–lvi; Bevir 2000, p. 168.

- ↑ Mortimer 1983, pp. 61–2; Garrity 2014, p. 18.

- ↑ Besant 1917, p. 27; Garrity 2014, p. 15.

- ↑ Bevir 2000, pp. 166, 169.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Britannica2.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Bevir 2000, p. 172.

- ↑ Barker 1924.

- ↑ Bevir 2003, p. 103; Garrity 2014, p. 13.

- ↑ Wedderburn 1913, p. 78; Johnson 1994, p. 234; Bevir 2000, p. 172.

- ↑ Bevir 2000, p. 172; Garrity 2014, p. 16.

- ↑ Hanes III 1993, p. 69; Garrity 2014, p. 17.

- ↑ Harris3.

- ↑ Bevir 2000, p. 173; Bevir 2003, p. 107.

- ↑ Wedderburn 1913, p. 64; Bevir 2000, p. 173.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Bevir 2000, p. 159.

- ↑ Bishop 1997, p. 145.

- ↑ Wessinger 1988, p. 79.

- ↑ Tenbroeck.

- ↑ Besant.

- ↑ Bevir 1991, p. 342; Bevir 2000, p. 173.

- ↑ Wessinger 1988, p. 80; Bevir 1991, p. 353.

- ↑ Roe 1979.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Bevir 2000, p. 174.

- ↑ Dwarkadas 1966, p. 35; Bevir 2000, p. 174.

- ↑ Wessinger 1988, p. 82.

- ↑ Bevir 2000, p. 174; Garrity 2014, p. 18.

- ↑ Hanes III 1993, p. 69; Garrity 2014, p. 18.

- ↑ Stuckrad 2005, p. 127.

- ↑ Fischer 1951, p. 44.

- ↑ Brooks.

- ↑ Gandhi 1983, p. 60.

- ↑ Nehru 1941.

- ↑ Harris; Swarup.

- ↑ Stuckrad 2005, p. 126.

- ↑ Cranston 1993, p. 192; Stuckrad 2005, pp. 126–7.

- ↑ Harris2.

- ↑ Norris 1981.

- ↑ Harris; Oliveira.

- ↑ Lansbury 1928, p. 6; Postgate 1951, p. 58.

- ↑ Harris4.

- ↑ Hodgson.

- ↑ Hodgson 1885, p. 314.

- ↑ Washington 1995, p. 85.

- ↑ Washington 1995, Ch. 6.

Sources[edit]

- "Hinduism: the modern period". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc. 2019. Retrieved 2019-04-15.

- "Allan Octavian Hume: British colonial official". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc. 2019. Retrieved 2019-04-15.

- Besant A. (17 October 1914). "On the Congress' political role". New India. Madras: A. Besant. p. 5. OCLC 987253609.

- ———— (1915). How India Wrought For Freedom. Adyar: Theosophical Publishing House. Search this book on

- ———— (1917). The case for India: The presidential address. Search this book on

- Bevir, M. (July 1991). "The Formation of the All-India Home Rule League". The Indian Journal of Political Science. Indian Political Science Association. 52 (3): 341–56. JSTOR 41855566.

- ———— (2000). "Theosophy as a Political Movement". In Copley, Antony. Gurus and Their Followers. Oxford University Press. pp. 159–79. ISBN 9780195649581. Retrieved 2 May 2019. Search this book on

- ———— (2003). "Theosophy and the Origins of the Indian National Congress". International Journal of Hindu Studies. Berkeley: University of California, Berkeley. 7 (1/3): 99–115. doi:10.1007/s11407-003-0005-4. Retrieved 2 May 2019.

- Bishop, D. H. (1997). "Annie Besant and the Theosophical Society". Thinkers of the Indian Renaissance (2nd ed.). New Delhi: New Age International. pp. 143–69. ISBN 9788122411225. Retrieved 2 May 2019. Search this book on

- Brooks R. W. (15 December 2011). "Gandhi, Mohandas Karamchand". Theosopedia. Manila: Theosophical Publishing House. Retrieved 2019-04-15.

- Dwarkadas, Kanji (1966). India's Fight for Freedom, 1913-1937: An Eyewitness Story. Popular Prakashan. Retrieved 2 May 2019. Search this book on

- Fischer, L. (1951). Mahatma Gandhi – His Life & Times (PDF). London: Jonathan Cape. Retrieved 2 May 2019. Search this book on

- Gandhi, M. (1983). Autobiography: The Story of My Experiments with Truth. Social Sciences Series. Translated by Desai, M. H. (Reprint ed.). Courier Corporation. ISBN 9780486245935. Retrieved 2 May 2019. Search this book on

- Garrity, C. (2014). Storm, Mary, ed. "Alternative Histories: Observing Theosophical 'Truths' in Hindu Nationalism". Independent Study Project Collection. Retrieved 2 May 2019.

- Goodrick-Clarke, N. (2004). Helena Blavatsky. Western esoteric masters series. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books. ISBN 978-1-55643-457-0. Retrieved 2 May 2019. Search this book on

- Hanes III, W. T. (1993). "On the Origins of the Indian National Congress". Journal of World History. University of Hawai'i Press. 4 (1): 69–98. JSTOR 20078547.

- Hodgson, R. (1885-09-12). "The Theosophical Society. Russian Intrigue or Religious Evolution?". The Age. Melbourne. Retrieved 2019-04-15.

- Hodgson, R.; et al. (1885). "Report of the committee appointed to investigate phenomena connected with the Theosophical Society" (PDF). Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research. London: Society for Psychical Research. 3: 201–400. ISSN 0081-1475.

- Johnson, K. P. (1994). "Who inspired Hume?". The Masters Revealed. SUNY series in Western esoteric traditions. Albany: State University of New York Press. pp. 234–41. ISBN 9780791420638. Retrieved 2 May 2019. Search this book on

- Lansbury, G. (1928). My Life. Constable and Company Limited. Retrieved 2 May 2019. Search this book on

- Mortimer, Joanne S. (January 1983). "Annie Besant and India 1913–1917". Journal of Contemporary History. London: Sage Publications. 18 (1): 61–78. doi:10.1177/002200948301800104. JSTOR 260481.

- Nehru, J. (1941). "Theosophy". Toward Freedom: The Autobiography of Jawaharlal Nehru. The John Day Company. pp. 26–30. Search this book on

- Norris, R. (1981). "Deakin, Alfred (1856–1919)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. 8. Retrieved 2019-05-02.

- Postgate, R. (1951). The Life of George Lansbury. Longmans, Green. Retrieved 2 May 2019. Search this book on

- Roe, J. (1979). "Arundale, George Sydney (1878–1945)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. 7. Retrieved 2019-05-02.

- Stuckrad, K. (2005). Western Esotericism: A Brief History of Secret Knowledge. Translated by Goodrick-Clarke, N. London: Equinox Publishing. ISBN 9781845530334. Retrieved 2 May 2019. Search this book on

- Washington, P. (1995). Madame Blavatsky's baboon: a history of the mystics, mediums, and misfits who brought spiritualism to America. Schocken Books. ISBN 9780805241259. Retrieved 2 May 2019. Search this book on

- Wedderburn, W. (1913). Allan Octavian Hume: Father of the Indian National Congress, 1829–1912. London: Fisher Unwin. Search this book on

- Wessinger, C. L. (1988). Annie Besant and Progressive Messianism (1847-1933). Studies in women and religion. E. Mellen Press. ISBN 9780889465237. Retrieved 2 May 2019. Search this book on

- ———— (10 March 2012). "Besant, Annie". Theosopedia. Manila: Theosophical Publishing House. Retrieved 2019-04-15.

- Трефилов, В. А. (2005). "Глава XVII. Надконфессиональная синкретическая религиозная философия" [Chapter XVII. Non-denominational syncretic religious philosophy]. In Яблоков, И. Н. Основы религиоведения [Fundamentals of the Religious Studies]. Классический университетский учебник (in Russian) (4th ed.). Москва: Высшая школа. pp. 364–81. ISBN 978-5060042542.CS1 maint: Unrecognized language (link) Search this book on

- Theosophical publications

- Kuthumi; et al. (1924). Barker, A. T., ed. The Mahatma Letters to A. P. Sinnett from the Mahatmas M. & K. H. New York: Frederick A. Stokes Company Publishers. Retrieved 2 May 2019. Search this book on

- Blavatsky, H. P. (October 1879). "What Are The Theosophists?" (PDF). The Theosophist. Bombay: Theosophical Society. 1 (1): 5–7. Retrieved 2 May 2019.

- Cranston, S. L. (1993). HPB: the extraordinary life and influence of Helena Blavatsky, founder of the modern Theosophical movement. G.P. Putnam's Sons. ISBN 9780874776881. Retrieved 2 May 2019. Search this book on

- Harris P. S. (7 December 2011). "Deakin, Alfred". Theosopedia. Manila: Theosophical Publishing House. Retrieved 2019-04-15.

- Harris P. S. (12 March 2012). "Hume, Allan Octavian". Theosopedia. Manila: Theosophical Publishing House. Retrieved 2019-04-15.

- Harris P. S. (15 March 2012). "Lansbury, George". Theosopedia. Manila: Theosophical Publishing House. Retrieved 2019-04-15.

- Harris, P. S.; Oliveira, L. (23 November 2012). "Australia, Theosophy in". Theosopedia. Manila: Theosophical Publishing House. Retrieved 2019-04-15.

- Harris, P. S.; Swarup, B. N. (2 April 2012). "Nehru, Jawaharlal". Theosopedia. Manila: Theosophical Publishing House. Retrieved 2019-04-15.

- Olcott, H. S. (July 1883). "Politics and Theosophy" (PDF). The Theosophist. Adyar: Theosophical Society. 4 (46): 14. Retrieved 2 May 2019.

- Tenbroeck D. (14 March 2012). "Wadia, Bahmanji Pestonji". Theosopedia. Manila: Theosophical Publishing House. Retrieved 2019-04-15.

Further reading[edit]

- Harris P. S. (12 March 2012). "Das, Bhagavan". Theosopedia. Manila: Theosophical Publishing House. Retrieved 2019-04-15.

- Jinarajadasa, C. (September 1923). "The Divine Wisdom and Politics" (PDF). The Theosophist. Adyar: Theosophical Society. 44: 643–8. Retrieved 2 May 2019.

- Tenbroeck D. "B. P. Wadia – A Life of Service to Mankind". katinkahesselink.net. Katinka Hesselink. Retrieved 2019-04-15.

External links[edit]

This article "Theosophy and politics" is from Wikipedia. The list of its authors can be seen in its historical and/or the page Edithistory:Theosophy and politics. Articles copied from Draft Namespace on Wikipedia could be seen on the Draft Namespace of Wikipedia and not main one.