Lahore Front

This article's tone or style may not reflect the encyclopedic tone used on Wikipedia. (November 2020) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

| Battle of Lahore | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Indo-Pakistani War of 1965 | |||||||||

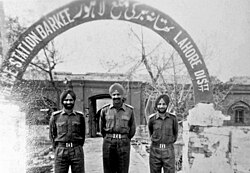

Lt. Col. Hari Singh of the Indian 18th Cavalry posing outside a captured Pakistani police station (Barkee) with fellow soldiers in Lahore District. | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

(Commander, XI Corps) |

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

100,000+ 1 armoured division |

50,000 2 armoured divisions | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | ||||||||

The Battle of Lahore (Urdu: جنگِ لاہور; Jang-e-Lāhaur, Hindi: लाहौर की लड़ाई; Lāhaur kī laḍ.āī), also referred to as the Lahore Front, constitutes a series of battles fought in and around the Pakistani city of Lahore during the Indo-Pakistani War of 1965.[Note 1] The battle ended in a victory for India, as it was able to thrust through and hold key choke points in Pakistan while having gained around 360 to 500 square kilometres of territory. Indian forces halted their assault on Lahore once they had captured the village of Burki on its outskirts.[9][10][11][12] The rationale for this was that a ceasefire−negotiated by the United States and the Soviet Union−was to be signed soon, and had India captured Lahore, It would have most likely been returned to the process of ceasefire negotiations.[10][11][12]

Prelude[edit]

After losing hope in the likelihood of a plebiscite being conducted in Kashmir, the Pakistan Army sent infiltrators into the Indian-administered state of Jammu and Kashmir through a covert operation, dubbed Operation Gibraltar, with the aim of stirring unrest among the Kashmiri locals against Indian rule and instigating a rebellion.[13][14] The operation failed due to a variety of contributing factors,[15] and the infiltrators' presence was soon disclosed to the Indian military. India responded by deploying more troops in the Kashmir Valley and the Indian Army subsequently began its assault against the infiltrators operating in the region. Pakistan launched a major offensive named Operation Grand Slam on 1 September 1965 in Indian-administered Jammu and Kashmir,[16] in an effort to relieve pressure on the infiltrators who had been surrounded and were holding out against Indian forces after the failure of Operation Gibraltar. Operation Grand Slam also aimed to assault and capture the Akhnoor bridge, which would not only cut off Indian supply lines, but also allow the Pakistani military to threaten Jammu, an important logistical point for Indian forces.[13][17] The operation saw Pakistani forces go on the offensive and aggressively push into and take strategically vital points in Kashmir. In order to relieve the mounting pressure on the Kashmir front, India's counterattack saw its forces crossing the international border and invading the Pakistani province of Punjab, with the intention of diverting Pakistan's military units in Kashmir, where Indian troops were at a severe disadvantage.[13]

The battle[edit]

On the night of 5–6 September 1965, Indian XI Corps began its operations by advancing towards Lahore along three axes – Amritsar-Lahore, Khalra-Burki- Lahore and Khem Karan-Kasur roads, overwhelming the small Pakistani force.[18] Pakistan's 10 and 11 Divisions, which were deployed in the sector, began a series of rather confused delaying actions, and by the end of the first day the Indian infantry, backed by heavy armoured troops, were within striking distance of Lahore city. Some advance Indian units managed to capture Ichhogil canal on 6 September, but soon withdrew, since support and reinforcements were not expected to reach any time soon.[5]

Pakistani soon launched a three-pronged counterattack to counter Indian assault on 8 September[19] backed by its newly created 1 and 6 Armoured division to break through the front line formed by Indian 4 Grenadiers, 9 Jammu and Kashmir rifles, 1 & 9 Gurkha rifles and Rajput Rifles.[20]

On 8th, Pakistan began a counterattack south of Lahore from Kasur towards Khem Karan, an Indian town 5 km from the International Border. This was followed by another major armoured on 9 and 10 September to recapture lost ground despite heavy toll on Pakistani armour.[20] The Pakistani counterattack led to the capture of the village Khem Karan.[21] However, a massive Indian counterattack repulsed the Pakistani forces from this sector of Indian territory. Continued heavy attrition specially on Pakistani armour however meant Pakistan could not continue the counterattack from 10 onwards.[20]

Along the Amritsar-Lahore and Khalra-Burki-Lahore axis in middle Indian infantry won decisive battle at Burki.[19] Pakistani counterattack which started on 8th Pakistani artillery pounding Indian advance on 8,9 and 10 September.[3] Indian units continued their advance, and by 22 September, had reached the Ichhogil canal protecting the city of Lahore.[1] Pakistani counterattacks were effectively tackled at Burki with little armour support on 10th punishing Pakistani armour.[19] Indian advance then moved on to capture Dograi, a town in the immediate vicinity of Lahore.[5] After reaching the outskirts of Lahore Indian Army ensured that Lahore came under constant Indian tank fire to prepare for the main assault on Lahore city before ceasefire was announced.[6]

In the north India won another decisive battle at Phillora supported by its 1 Armoured Division on 11th destroying the Pakistani counterattack.[5] Indians continued to advance towards Chawinda in the north from Phillora and reached Chawinda by 17 September.[22] However, they were halted at Chawinda till ceasefire on 22 September. This was a result of the exceptional defences backed by artillery were created by Pakistani Brigadier A.A.K. Niazi who had started preparing the defences soon after fall of Phillora. The Indian attack in the north only lost momentum at the Battle of Chawinda, after more than 500 km2 of Pakistani territory had been captured.[7] The Pakistanis were helped by the fact that the network of canals and streams in the sector made for natural defensive barriers. In addition, the prepared defence, comprising minefields, dugouts and more elaborate pillboxes, proved problematic for the Indians.[1]

Aftermath[edit]

Even after the capture of Dograi on 20–21 September, no attempt was made to capture Lahore and the main assault on Lahore was not launched because a ceasefire was to be signed in the following couple of days and it was known that the city would have been given back to Pakistan even if it was captured.[23] By choosing to attack Lahore, the Indians had managed to relieve pressure from Chumb and Akhnoor in Kashmir, forcing the Pakistan Army to defend further south.[1]

At the end of hostilities on 23 September India retained between 140 square miles and 360 square kilometres of Pakistani territory in the Lahore front including major villages of Bedian, Barki, Padri, Dograi, Bhasin and Ichhogil Uttar along the eastern bank of the Ichhogil canal. Pakistan only gained a small tract of land around Khem Karan of 50 square kilometres.[24][25]

Gallantry and awards[edit]

The Fighting Fifth Battalion of Indian Army which played an important part in capturing Burki was later conferred with "Battle Honour of Burki" and "Theatre of Honour, Punjab".[26]

The Pakistani commander, Major Raja Aziz Bhatti, was later awarded the Nishan-e-Haider, the highest military decoration given by Pakistan for the Battle of Burki, posthumously. Each year, he is honoured in Pakistan on 6 September, which is also known as Defence Day.[27]

Notes[edit]

- ↑ Also known as the Second Kashmir War.

References[edit]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Praagh, David (2003). The greater game: India's race with destiny and China. McGill-Queen's Press – MQUP, 2003. p. 294. ISBN 978-0-7735-2639-6. Search this book on

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Hagerty, Devin (2005). South Asia in world politics. Rowman & Littlefield, 2005. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-7425-2587-0. Search this book on

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Gupta, Hari Ram. India-Pakistan war, 1965, Volume 1. Hariyana Prakashan, 1967. Search this book on

- ↑ Dandavate, Madhu (2005). Dialogue with Life. Allied Publishers Pvt Ltd. ISBN 978-81-7764856-0. Search this book on

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Wilson, Peter (2003). Wars, proxy-wars and terrorism: post independent India. Mittal Publications, 2003. ISBN 978-81-7099-890-7. Search this book on

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 The new encyclopaedia Britannica. Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2002. ISBN 978-0-85229-787-2. Search this book on

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Musharraf, In the Line of Fire, page 45.

- ↑ "File:Lt.Col SarfaraZ Khan.jpg", Wikipedia, 2011-12-04, retrieved 2020-11-04 External link in

|title=(help) - ↑ Melville de Mellow (28, November 1965). "Battle of Burki was another outstanding infantry operation". Sainik Samachar.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Hagerty, Devin. South Asia in world politics. Rowman & Littlefield, 2005. ISBN 0-7425-2587-2 Search this book on

..

..

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 William M. Carpenter, David G. Wiencek. Asian security handbook: terrorism and the new security environment. M.E. Sharpe, 2005. ISBN 0-7656-1553-3 Search this book on

..

..

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 John Keay. India: A History. Grove Press, 2001. ISBN 0-275-97779-X Search this book on

..

..

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 "Indo-Pakistan War of 1965". globalsecurity.org.

- ↑ Faruqui, Ahmad (2018-08-06). "Why did Operation Gibraltar fail?". Daily Times. Archived from the original on 2020-07-05. Retrieved 2020-10-31. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ M. Hali, Sultan (2012-03-21). "Operation Gibraltar—An Unmitigated Disaster?". Criterion Quarterly. Archived from the original on 2020-10-31. Retrieved 2020-10-31. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ GILLANI, M. A. (2013). "Tawi to Chak Kirpal September 1965 War". Defence Journal. 17 (2): 64 – via EBSCO.

- ↑ Bajwa, Farooq (2013). From Kutch to Tashkent: The Indo-Pakistani War of 1965. Hurst. ISBN 978-1849042307. Search this book on

- ↑ Johri, Sitaram. The Indo-Pak conflict of 1965. Himalaya Publications, 1967. pp. 129–130. Search this book on

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 "Untitled Document".

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Bajwa, Kuldip Singh. The Dynamics of Soldiering. Har-Anand Publication Pvt Ltd. Search this book on

- ↑ Pradhan, R. D. (2007). 1965 war, the inside story: Defence Minister Y.B. Chavan's diary of India Pakistani War. Atlantic Publishers & Dist. ISBN 978-81-269-0762-5. Search this book on

- ↑ Rao, K. V. Krishna (1991). Prepare or perish: a study of national security. Lancers Publishers, 1991. ISBN 978-81-7212-001-6. Search this book on

- ↑ James Rapson, Edward; Wolseley Haig; Richard Burn; Henry Dodwell; Robert Eric Mortimer Wheeler; Vidya Dhar Mahajan. "Political Developments Since 1919 (India and Pakistan)". The Cambridge History of India. 6. S. Chand. p. 1013. Search this book on

- ↑ Singh, Lt. Gen. Harbaksh (1991). War Despatches. Lancer International. p. 124. ISBN 81-7062-117-8. Search this book on

- ↑ Rakshak, Bharat. "Official History Of 1965 war chapt 11, pg 22" (PDF). The Times of India. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 December 2018. Retrieved 11 July 2011. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ "War memorial inaugurated". Tribune News service. 25 August 2010. Retrieved 7 April 2011.

- ↑ "Major Raja Aziz Bhatti". Nishan-i-Haider recipients. Pakistan Army. Archived from the original on 3 October 2013. Retrieved 25 September 2013. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help)

Further reading[edit]

- Harry Chinchinian, India Pakistan in War and Peace ISBN 0-415-30472-5 Search this book on

.

.

This article "Lahore Front" is from Wikipedia. The list of its authors can be seen in its historical and/or the page Edithistory:Lahore Front. Articles copied from Draft Namespace on Wikipedia could be seen on the Draft Namespace of Wikipedia and not main one.