International trade

| Part of a series on |

| World trade |

|---|

|

International trade is the exchange of capital, goods, and services across international borders or territories.[1] In most countries, such trade represents a significant share of gross domestic product (GDP). While international trade has existed throughout history (for example Uttarapatha, Silk Road, Amber Road, scramble for Africa, Atlantic slave trade, salt roads), its economic, social, and political importance has been on the rise in recent centuries. Carrying out trade at an international level is a more complex process than domestic trade. Trade takes place between two or more nations. Factors like the economy, government policies, markets, laws, judicial system, currency, etc. influence the trade. The political relations between two countries also influences the trade between them. Sometimes, the obstacles in the way of trading affect the mutual relationship adversly. To avoid this, international economic and trade organisations came up. To smoothen and justify the process of trade between countries of different economic standing, some international economic organisations were formed. These organisations work towards the facilitation and growth of international trade.

Characteristic of global trade[edit]

Trading globally gives consumers and countries the opportunity to be exposed to new markets and products. Almost every kind of product can be found in the international market: food, clothes, spare parts, oil, jewelry, wine, stocks, currencies, and water. Services are also traded: tourism, banking, consulting, and transportation. A product that is sold to the global market is an export, and a product that is bought from the global market is an import. Imports and exports are accounted for in a country's current account in the balance of payments.[2]

Industrialization, advanced technology, including transportation, globalization, multinational corporations, and outsourcing are all having a major impact on the international trade system. Increasing international trade is crucial to the continuance of globalization. Nations would be limited to the goods and services produced within their own borders without international trade. International trade is, in principle, not different from domestic trade as the motivation and the behavior of parties involved in a trade do not change fundamentally regardless of whether trade is across a border or not. The main difference is that international trade is typically more costly than domestic trade. This is due to the fact that a border typically imposes additional costs such as tariffs, time costs due to border delays, and costs associated with country differences such as language, the legal system, or culture.

Another difference between domestic and international trade is that factors of production such as capital and labor are typically more mobile within a country than across countries. Thus, international trade is mostly restricted to trade in goods and services, and only to a lesser extent to trade in capital, labour, or other factors of production. Trade in goods and services can serve as a substitute for trade in factors of production. Instead of importing a factor of production, a country can import goods that make intensive use of that factor of production and thus embody it. An example of this is the import of labor-intensive goods by the United States from China. Instead of importing Chinese labor, the United States imports goods that were produced with Chinese labor. One report in 2010 suggested that international trade was increased when a country hosted a network of immigrants, but the trade effect was weakened when the immigrants became assimilated into their new country.[3]

History[edit]

The history of international trade chronicles notable events that have affected the trade among various economies.

Models[edit]

There are several models which seek to explain the factors behind international trade, the welfare consequences of trade and the pattern of trade.

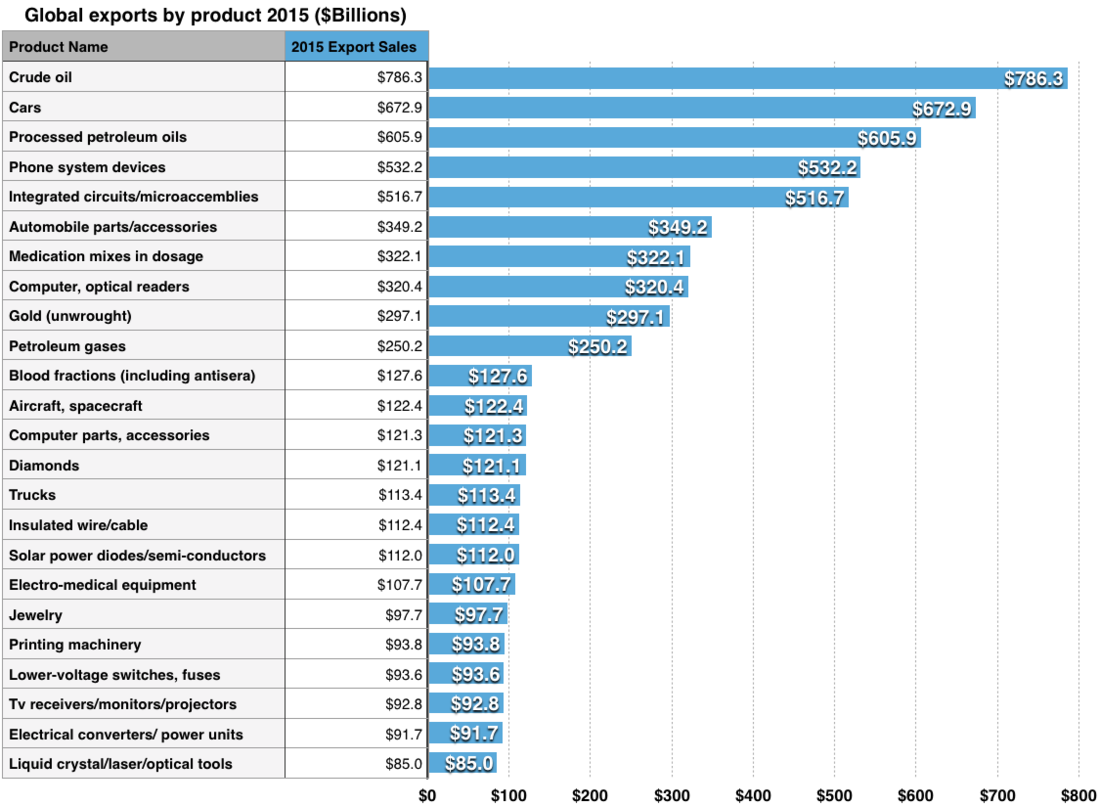

Most traded export products[edit]

Largest countries by total international trade[edit]

The following table is a list of the 21 largest trading nations according to the World Trade Organization.[4][not in citation given]

| Rank | Country | International trade of goods (billions of USD) |

International trade of services (billions of USD) |

Total international trade of goods and services (billions of USD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| – | World | 32,430 | 9,635 | 42,065 |

| – | 3,821 | 1,604 | 5,425 | |

| 1 | 3,706 | 1,215 | 4,921 | |

| 2 | 3,686 | 656 | 4,342 | |

| 3 | 2,626 | 740 | 3,366 | |

| 4 | 1,066 | 571 | 1,637 | |

| 5 | 1,250 | 350 | 1,600 | |

| 6 | 1,074 | 470 | 1,544 | |

| 7 | 1,073 | 339 | 1,412 | |

| 8 | 1,064 | 172 | 1,236 | |

| 9 | 902 | 201 | 1,103 | |

| 10 | 866 | 200 | 1,066 | |

| 11 | 807 | 177 | 984 | |

| 12 | 763 | 212 | 975 | |

| 13 | 623 | 294 | 917 | |

| 13 | 613 | 304 | 917 | |

| 15 | 771 | 53 | 824 | |

| 16 | 596 | 198 | 794 | |

| 17 | 572 | 207 | 779 | |

| 18 | 511 | 93 | 604 | |

| 19 | 473 | 122 | 595 | |

| 20 | 248 | 338 | 586 | |

| 21 | 491 | 92 | 583 |

Top traded commodities (exports)[edit]

| Rank | Commodity | Value in US$('000) | Date of information |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mineral fuels, oils, distillation products, etc. | $2,183,079,941 | 2015 |

| 2 | Electrical, electronic equipment | $1,833,534,414 | 2015 |

| 3 | Machinery, nuclear reactors, boilers, etc. | $1,763,371,813 | 2015 |

| 4 | Vehicles other than railway | $1,076,830,856 | 2015 |

| 5 | Plastics and articles thereof | $470,226,676 | 2015 |

| 6 | Optical, photo, technical, medical, etc. apparatus | $465,101,524 | 2015 |

| 7 | Pharmaceutical products | $443,596,577 | 2015 |

| 8 | Iron and steel | $379,113,147 | 2015 |

| 9 | Organic chemicals | $377,462,088 | 2015 |

| 10 | Pearls, precious stones, metals, coins, etc. | $348,155,369 | 2015 |

Source: International Trade Centre[5]

Observances[edit]

President George W. Bush observed World Trade Week on May 18, 2001, and May 17, 2002.[6][7] On May 13, 2016, President Barack Obama proclaimed May 15 through May 21, 2016, World Trade Week, 2016.[8] On May 19, 2017, President Donald Trump proclaimed May 21 through May 27, 2017, World Trade Week, 2017.[9][10] World Trade Week is the third week of May. Every year the President declares that week, World Trade Week.[11][12]

See also[edit]

Other articles of the topic Business and economics : Economics

Some use of "" in your query was not closed by a matching "".Some use of "" in your query was not closed by a matching "".

- Aggressive legalism

- Comparison of imports vs exports of the United States

- Free trade

- Free trade area

- Gravity model of trade

- Import (international trade)

- Interdependence

- International business

- International trade law

- Internationalization

- Market Segmentation Index

- Mercantilism

- Monopolistic competition in international trade

- Tariff

- Trade Adjustment Assistance

- Trade bloc

- Trade finance

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD)

- Lists

- List of countries by current account balance

- List of countries by imports

- List of countries by exports

- List of international trade topics

Notes[edit]

- ↑ "Trade – Define Trade at Dictionary.com". Dictionary.com.

- ↑ Staff, Investopedia (2003-11-25). "Balance Of Payments (BOP)". Investopedia. Retrieved 2017-05-07.

- ↑ Kusum Mundra (October 18, 2010). "Immigrant Networks and U.S. Bilateral Trade: The Role of Immigrant Income". papers.ssrn. SSRN 1693334.

Mundra, Kusum, Immigrant Networks and U.S. Bilateral Trade: The Role of Immigrant Income. IZA Discussion Paper No. 5237. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1693334 ... this paper finds that the immigrant network effect on trade flows is weakened by the increasing level of immigrant assimilation.

- ↑ Leading merchandise exporters and importers, 2016

- ↑ International Trade Centre (ITC). "Trade Map - Trade statistics for international business development".

- ↑ Office of the Press Secretary (May 22, 2001). "World Trade Week, 2001" (PDF). Federal Register. Washington, D.C.: Federal Government of the United States. Archived from the original on May 22, 2001. Retrieved March 13, 2017.

- ↑ Office of the Press Secretary (May 22, 2002). "World Trade Week, 2002" (PDF). Federal Register. Washington, D.C.: Federal Government of the United States. Archived from the original on May 22, 2002. Retrieved March 12, 2017.

- ↑ "Presidential Proclamation -- World Trade Week, 2016". whitehouse.gov. Washington, D.C.: White House. May 13, 2016. Retrieved April 11, 2017.

- ↑ Office of the Press Secretary (May 19, 2017). "President Donald J. Trump Proclaims May 21 through May 27, 2017, as World Trade Week". whitehouse.gov. Washington, D.C.: White House. Retrieved May 20, 2017.

- ↑ "President Donald J. Trump Proclaims May 21 through May 27, 2017, as World Trade Week". World News Network. United States: World News Inc. May 20, 2017. Retrieved May 20, 2017.

- ↑ "Import Export Data". Import Export data. Retrieved 2017-10-06.

- ↑ "World Trade Week New York". World Trade Week New York. Retrieved 2017-10-06.

References[edit]

- Jones, Ronald W. (1961). "Comparative Advantage and the Theory of Tariffs". The Review of Economic Studies. 28 (3): 161–175. doi:10.2307/2295945.

- McKenzie, Lionel W. (1954). "Specialization and Efficiency in World Production". The Review of Economic Studies. 21 (3): 165–180. doi:10.2307/2295770.

- Samuelson, Paul (2001). "A Ricardo-Sraffa Paradigm Comparing the Gains from Trade in Inputs and Finished Goods". Journal of Economic Literature. 39 (4): 1204–1214. doi:10.1257/jel.39.4.1204.

External links[edit]

Data[edit]

Official statistics[edit]

Data on the value of exports and imports and their quantities often broken down by detailed lists of products are available in statistical collections on international trade published by the statistical services of intergovernmental and supranational organisations and national statistical institutes. The definitions and methodological concepts applied for the various statistical collections on international trade often differ in terms of definition (e.g. special trade vs. general trade) and coverage (reporting thresholds, inclusion of trade in services, estimates for smuggled goods and cross-border provision of illegal services). Metadata providing information on definitions and methods are often published along with the data.

- United Nations Commodity Trade Database

- Trade Map, trade statistics for international business development

- WTO Statistics Portal

- Indian Export Import Data

- Statistical Portal: OECD

- European Union International Trade in Goods Data

- Food and Agricultural Trade Data by FAO

Other data sources[edit]

- Resources for data on trade, including the gravity model

- Asia-Pacific Trade Agreements Database (APTIAD)

- Asia-Pacific Research and Training Network on Trade (ARTNeT)

- Export Import Data

- World Integrated Trade Solution (WITS)

- Market Access Map, an online database of customs tariffs and market requirements

- Export Import Trade Statistics

Other external links[edit]

- Import Export Data

- The Observatory of Economic Complexity

- The McGill Faculty of Law runs a Regional Trade Agreements Database that contains the text of almost all preferential and regional trade agreements in the world. ptas.mcgill.ca

- Historical documents on international trade available on FRASER