The NeuroGenderings Network

| Formation | September 15, 2012 |

|---|---|

| Founder | Isabelle Dussauge and Anelis Kaiser |

| Founded at | Uppsala, Sweden |

| Purpose | To critically examine neuroscientific knowledge production and to develop differentiated approaches for a more gender adequate neuroscientific research. |

| Fields | Critical neuroscientific research into sex differences |

| Website | Official website |

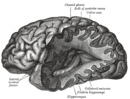

The NeuroGenderings Network is an international group of researchers in neuroscience and gender studies.[1] Members of the network study how the complexities of social norms, varied life experiences, details of laboratory conditions and biology all interact to affect the results of neuroscientific research.[2] Working under the label of "neurofeminism", they aim to critically analyze how the field of neuroscience operates, and to build an understanding of brain and gender that goes beyond gender essentialism while still treating the brain as fundamentally material.[3][4][5] Its founding was part of a period of increased interest and activity in interdisciplinary research connecting neuroscience and the social sciences.[6]

History[edit]

The group, comprising critical gender, feminist, and queer scholars, formed to tackle "neurosexism"[3] as defined by Cordelia Fine in her 2010 book Delusions of Gender "uncritical biases in [neuroscientific] research and public perception, and their societal impacts on an individual, structural, and symbolic level."[7]

By contrast they practice "neurofeminism"[8] to critically evaluate heteronormative assumptions of contemporary brain research and examine the impact and cultural significance of neuroscientific research on society's views about gender.[3][9] The network advocate greater emphasis to be placed on neuroplasticity rather than biological determinism.[3][10]

Conferences[edit]

In March 2010, the first conference – NeuroGenderings: Critical Studies of the Sexed Brain – was held in Uppsala, Sweden.[11][12][13] Organisers Anelis Kaiser and Isabelle Dussauge described its long terms goals "to elaborate a new conceptual approach of the relation between gender and the brain, one that could help to head gender theorists and neuroscientists to an innovative interdisciplinary place, far away from social and biological determinisms but still engaging with the materiality of the brain."[14] The NeuroGenderings Network was established at this event,[3][15] with the group's first results published in a special issue of the journal Neuroethics.[16][17]

Further conferences have since been held on a biennial basis:[18] NeuroCultures — NeuroGenderings II, September 2012 at the University of Vienna's physics department;[11][19][20][12][21][22] NeuroGenderings III – The First International Dissensus[23] Conference on Brain and Gender, May 2014 in Lausanne, Switzerland;[11][24][25][26] and NeuroGenderings IV in March 2016, at Barnard College, New York City.[27]

Members[edit]

The members of the NeuroGenderings Network are:[28]

- Robyn Bluhm

- Tabea Cornel

- Isabelle Dussauge

- Gillian Einstein

- Cordelia Fine

- Hannah Fitsch

- Giordana Grossi

- Christel Gumy

- Nur Zeynep Gungor

- Daphna Joel

- Rebecca Jordan-Young

- Anelis Kaiser

- Emily Ngubia Kessé

- Cynthia Kraus

- Victoria Pitts-Taylor

- Gina Rippon

- Deboleena Roy

- Raffaella Rumiati

- Sigrid Schmitz

- Catherine Vidal

Debates[edit]

Sex differences in human neonatal social perception[edit]

Non-network member, Simon Baron-Cohen, conducted a test on newborns – on average a day-and-a-half old – to see if they were more interested a human face (social object) or a mobile (physical-mechanical object). Baron-Cohen concluded that the results, based on the eye-gaze of the babies, "showed that the male infants showed a stronger interest in the physical-mechanical mobile while the female infants showed a stronger interest in the face" and the "research clearly demonstrates that sex differences are in part biological in origin."[29]

Network member, Cordelia Fine, criticized the experiment as being flawed for a number of reasons including: the expectations of the experimenter (graduate student, Jennifer Connellan), for example, unconsciously moving her head more / smiling more for a female baby.[30] In a review of Fine's book Baron-Cohen "we included a panel of independent judges coding the videotapes of just the eye-region of the baby’s face, from which it is virtually impossible to judge the sex of the baby."[31] In response Fine argued, "clearly, if the behaviour of the experimenter-cum-stimulus has already inadvertently influenced the babies’ eye gaze behaviour, the introduction of sex-blind judges is to close the stable door after the horse has bolted," and fellow network member Gina Rippon added, "the potential for misuse of our [neuroscientists] research should make us doubly careful of how (and why) we do research into these kinds of arenas, and how we report our findings. [...] Whether we like it or not, science and politics do mix."[32]

Gender differences when processing fear[edit]

In an fMRI study into the gender differences when processing fear, Schienle et al. (who are not part of The NeuroGenderings Network) began with an hypothesis that women would show a greater emotional response than men. In fact, the results showed the opposite. The researchers' explanation for the unexpected response pattern was that it "may reflect greater attention from males to cues of aggression in their environment."[33]

Network member Robyn Bluhm criticized the initial hypothesis, that women would show a greater emotional response than men, as stereotyping. She also criticized the researchers' explanation for the unexpected results, as they discounted the possibility that men may be more sensitive to fear than women.[34]

Female brain / male brain versus "mosaics" of brain features[edit]

An article by Tracey Shors found "sex differences in emotional and cognitive responses in rats" and she advised that her findings "be used to better understand and promote mental health in humans" as "a greater appreciation of our [sex] differences can only enhance our ability to treat our common afflictions."[35]

By comparison, the research carried out by network member Daphna Joel et al. found that "between 55% and 70% of people had a “mosaic” of gender characteristics, compared to less than one per cent who had only “masculine” or only “feminine” characteristics."[36]

See also[edit]

- Feminist movements and ideologies

- Heteronormativity

- Gender essentialism

- Neuroscience of sex differences

References[edit]

- ↑ Breit, Lisa (1 March 2016). "Genderforschung: Das Soziale an der Biologie". Der Standard (in Deutsch). Retrieved 26 October 2018.

- ↑ Krichmayr, Karin (24 May 2017). "Geschlechterunterschiede: Das Spiel der Hormone im Hirn". Der Standard (in Deutsch). Retrieved 26 October 2018.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Schmitz, Sigrid; Höppner, Grit (25 July 2014). "Neurofeminism and feminist neurosciences: a critical review of contemporary brain research". Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. Frontiers. 8 (article 546): 1–10. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2014.00546. PMC 4111126.

- ↑ Dussauge, Isabelle; Anelis, Anelis (13 April 2015). "Feminist and queer repoliticizations of the brain". EspacesTemps.net | Brain Mind Society. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ↑ Roy, Deboleena (Spring 2016). "Neuroscience and feminist theory: a new directions essay". Signs. Chicago Journals. 41 (3): 531–552. doi:10.1086/684266.

- ↑ Callard, F.; Fitzgerald, D. (2016). Rethinking Interdisciplinarity across the Social Sciences and Neurosciences. Palgrave Macmillan. OCLC 1014459177. Search this book on

- ↑ Fine, Cordelia (2010). Delusions of gender: how our minds, society, and neurosexism create difference. New York: W.W. Norton. ISBN 9780393068382. Search this book on

- ↑ Bluhm, Robyn; Maibom, Heidi Lene; Jaap Jacobson, Anne (2012). Neurofeminism: issues at the intersection of feminist theory and cognitive science. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9780230296732. Search this book on

- ↑ Kaiser, Anelis; Dussauge, Isabelle (2014), "Re-queering the brain", in Bluhm, Robyn; Jacobson, Anne Jaap; Maibom, Heidi Lene, Neurofeminism: issues at the intersection of feminist theory and cognitive science, Hampshire New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 121–144, ISBN 9781349333929.

- ↑ Vidal, Catherine (December 2012). "The sexed brain: between science and ideology". Neuroethics, special issue: Neuroscience and Sex/Gender. Springer. 5 (3): 295–303. doi:10.1007/s12152-011-9121-9.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Kraus, Cynthia (2016), "What is the feminist critique of neuroscience? A call for dissensus studies (notes to page 100)", in de Vos, Jan; Pluth, Ed, eds. (2016). Neuroscience and critique: exploring the limits of the neurological turn. London New York: Routledge. p. 113. ISBN 9781138887350. Search this book on

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 MacLellan, Lila (27 August 2017). "The biggest myth about our brains is that they are "male" or "female"". Quartz. Retrieved 26 October 2018.

- ↑ Engh Førde, Kristin (30 April 2010). "Tverrfaglig forståelse". Forskning.no (in norsk). Retrieved 26 October 2018.

- ↑ "NeuroGenderings: Critical Studies of the Sexed Brain". genna.gender.uu.se. Uppsala University, Sweden. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- ↑ "The body/Embodiment group". genna.gender.uu.se. Uppsala University, Sweden. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- ↑ Kaiser, Anelis; Dussauge, Isabelle (December 2012). "Neuroscience and sex/gender". Neuroethics, special issue: Neuroscience and Sex/Gender. Springer. 5 (3): 211–216. doi:10.1007/s12152-012-9165-5.

- ↑ Wills, Ben (2017-03-14). "What is Feminist Neuroethics About?". The Neuroethics Blog. Emory University. Retrieved 2018-10-27.

- ↑ Chaperon, Sylvie (15 May 2018). "Neuroféminisme contre neurosexisme". Libération (in français). Retrieved 26 October 2018.

- ↑ "Welcome to NeuroCultures - NeuroGenderings II". univie.ac.at. University of Vienna. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- ↑ Gupta, Kristina (2 October 2012). "A Dispatch from the NeuroGenderings II Conference". The Neuroethics Blog. Emory University. Retrieved 26 October 2018.

- ↑ Conrads, Judith. "NeuroCultures – NeuroGenderings II. Konferenz vom 13. bis 15. September 2012 an der Universität Wien". Gender: Zeitschrift für Geschlect, Kultur und Gesellschaft. 5 (1): 138–143.

- ↑ Dachs, Augusta (2012-09-12). "Lesen aus der Gehirnstruktur". Der Standard (in Deutsch). Retrieved 2018-10-27.

- ↑ A term expressing the idea that disagreement and social conflict are necessary parts of the discovery process: Fitzgerald, Des (2016-08-01). "Book review: Neuroscience and Critique: Exploring the Limits of the Neurological Turn". History of the Human Sciences.

- ↑ ""NeuroGenderings III – The 1st international Dissensus Conference on brain and gender," Lausanne, 8-10 May 2014". genrepsy.hypotheses.org. Genre et psychiatrie. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- ↑ Pulver, Jonas (5 May 2014). "Le sexe du cerveau ne fait pas consensus". Le Temps (in français). Retrieved 26 October 2018.

- ↑ "NeuroGenderings III Conference Recap" (PDF). International Neuroethics Society Newsletter. International Neuroethics Society. September 2014. Retrieved 2018-10-27.

- ↑ "2016 Seed Grants". Center for Science and Society. Columbia University. Retrieved 26 October 2018.

- ↑ "Members". neurogenderings.wordpress.com. The NeuroGenderings Network. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- ↑ Connellan, Jennifer; Baron-Cohen, Simon; Wheelwright, Sally; Batkia, Anna; Ahluwaliab, Jag (January 2000). "Sex differences in human neonatal social perception". Infant Behavior and Development. Elsevier. 23 (1): 113–119. doi:10.1016/S0163-6383(00)00032-1.

- See also: Baron-Cohen, Simon (2007), "Sex differences in mind: keeping science distinct from social policy", in Ceci, Stephen; Williams, Wendy M., Why aren't more women in science? Top researchers debate the evidence, Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, ISBN 9781591474852.

- ↑ Nash, Alison; Grossi, Giordana (2007). "Picking Barbie™'s brain: inherent sex differences in scientific ability?". Journal of Interdisciplinary Feminist Thought, special issue: Women and Science. Digital Commons. 2 (1): 29–42. Pdf.

- Cited in: Fine, Cordelia (2010), "The 'fetal fork'", in Fine, Cordelia (ed.). Delusions of Gender. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. p. 84. ISBN 9780393068382. Search this book on

- Cited in: Fine, Cordelia (2010), "The 'fetal fork'", in Fine, Cordelia (ed.). Delusions of Gender. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. p. 84. ISBN 9780393068382. Search this book on

- ↑ Baron-Cohen, Simon (November 2010). "Delusions of gender – 'neurosexism', biology and politics (book review)". The Psychologist. British Psychological Society. 23 (11): 904–905.

- ↑ Rippon, Gina; Fine, Cordelia (December 2010). "Forum: Seductive arguments?". The Psychologist. British Psychological Society. 23 (11): 948–949.

- ↑ Schienle, Anne; Schäfer, Axel; Stark, Rudolf; Walter, Bertram; Vaitl, Dieter (28 February 2005). "Gender differences in the processing of disgust- and fear-inducing pictures: an fMRI study". NeuroReport. LWW. 16 (3): 277–280. PMID 15706235.

- ↑ Turk, Victoria (28 November 2014). "You can't just reduce neurological differences to "women can't read maps"". Motherboard. Retrieved 25 August 2017.

- See also: Bluhm, Robyn (Fall 2013). "Self-fulfilling prophecies: the influence of gender stereotypes on functional neuroimaging research on emotion". Hypatia. Wiley. 28 (4): 870–886. doi:10.1111/j.1527-2001.2012.01311.x.

- ↑ Shors, Tracey J. (June 2002). "Opposite effects of stressful experience on memory formation in males versus females" (PDF). Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, special issuel: CNS aspects of reproductive endocrinology. Laboratoires Servier. 4 (2): 139–147. PMC 3181678.

- ↑ Joel, Daphna; Fine, Cordelia (1 December 2015). "It's time to celebrate the fact that there are many ways to be male and female". The Guardian. Guardian Media Group. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- See also: Joel, Daphna; et al. (15 December 2015). "Sex beyond the genitalia: The human brain mosaic". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. National Academy of Sciences. 112 (50): 15468–15473. doi:10.1073/pnas.1509654112. PMC 4687544. PMID 26621705.

Works cited[edit]

- Books

- Fine, Cordelia (2010). Delusions of gender: how our minds, society, and neurosexism create difference. New York: W.W. Norton. ISBN 9780393068382. Search this book on

- Bluhm, Robyn; Maibom, Heidi Lene; Jaap Jacobson, Anne (2012). Neurofeminism: issues at the intersection of feminist theory and cognitive science. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9780230296732. Search this book on

Also available to view by chapter online.

Also available to view by chapter online. - Schmitz, Sigrid; Höppner, Grit, eds. (2014). Gendered neurocultures: feminist and queer perspectives on current brain discourses. challenge GENDER, 2. Wien: Zaglossus. ISBN 9783902902122. Search this book on

- Book chapters

- Kaiser, Anelis (2010), "Sex/Gender and neuroscience: focusing on current research", in Blomqvist, Martha; Ehnsmyr, Ester, Never mind the gap! Gendering science in transgressive encounters, Uppsala Sweden: Skrifter från Centrum för genusvetenskap. University Printers, pp. 189–210, ISBN 9789197818636.

- Schmitz, Sigrid (2014), "Sex, gender, and the brain – biological determinism versus socio-cultural constructivism", in Klinge, Ineke; Wiesemann, Claudia, Sex and gender in biomedicine: theories, methodologies, results, Akron, Ohio: University Of Akron Press, pp. 57–76, ISBN 9781935603689.

- Kaiser, Anelis; Dussauge, Isabelle (2014), "Re-queering the brain", in Bluhm, Robyn; Japp Jacobson, Anne; Maibom, Heidi Lene, Neurofeminism: issues at the intersection of feminist theory and cognitive science, Hampshire New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 121–144, ISBN 9781349333929.

- Kraus, Cynthia (2016), "What is the feminist critique of neuroscience? A call for dissensus studies", in de Vos, Jan; Pluth, Ed (eds.). Neuroscience and critique: exploring the limits of the neurological turn. London New York: Routledge. pp. 100–116. ISBN 9781138887350. Search this book on

- Journal articles

- Hyde, Janet Shibley (September 2005). "The gender similarities hypothesis". American Psychologist. American Psychological Association via PsycNET. 60 (6): 581–592. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.60.6.581. PMID 16173891.

- Nash, Alison; Grossi, Giordana (2007). "Picking Barbie™'s brain: inherent sex differences in scientific ability?". Journal of Interdisciplinary Feminist Thought, special issue: Women and Science. Springer. 2 (1): 5. Pdf.

- Schmitz, Sigrid; Höppner, Grit (25 July 2014). "Neurofeminism and feminist neurosciences: a critical review of contemporary brain research". Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. Frontiers. 8 (article 546): 1–10. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2014.00546. PMC 4111126.

- Roy, Deboleena (Spring 2016). "Neuroscience and feminist theory: a new directions essay". Signs. Chicago Journals. 41 (3): 531–552. doi:10.1086/684266.

- Opposing publications

Below is a list of works which cause the network concern due to their "neurodeterminist notions of a ‘sexed brain’ [which] are being transported into public discourse without reflecting the biases in empirical work."

- Source: Schmitz and Höppner (2014).

- Pease, Allan; Pease, Barbara (2001). Why men don't listen & women can't read maps. Sydney, NSW: Pease International. ISBN 9780957810815. Search this book on

- Cahill, Larry (October 1, 2012). "His brain, her brain". Scientific American. Springer Nature. 292 (5): 22–29. PMID 15882020.

- Cahill, Larry (January–February 2017). "An issue whose time has come (editorial)". Journal of Neuroscience Research, special issue: an Issue Whose Time Has Come: Sex/Gender Influences on Nervous System Function. Wiley. 95 (1–2): 12–13. doi:10.1002/jnr.23972.

- Brizendine, Louann (2009). The female brain. London: Bantham. ISBN 9781407039510. Search this book on

- Brizendine, Louann (2011). The male brain. Edinburgh: Harmony. ISBN 9780767927543. Search this book on

- Gray, John (2004). Men are from Mars, women are from Venus: the classic guide to understanding the opposite sex. New York: HarperCollins Publishers. ISBN 9780060574215. Search this book on

External links[edit]

This article "The NeuroGenderings Network" is from Wikipedia. The list of its authors can be seen in its historical and/or the page Edithistory:The NeuroGenderings Network. Articles copied from Draft Namespace on Wikipedia could be seen on the Draft Namespace of Wikipedia and not main one.