Deccani Urdu

| Deccani | |

|---|---|

| دکنی | |

A folio from the Kitab-i-Navras, a collection of Deccani poetry attributed to the Adil Shahi king Ibrahim Adil Shah II (16th-17th centuries) | |

| Native to | India |

| Region | Deccan Maharashtra Karnataka Telangana Andhra Pradesh Tamil Nadu Goa |

| Ethnicity | Deccanis |

Standard forms | |

| Dialects |

|

| Perso-Arabic (Urdu alphabet) | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | dakh1244[1] |

Deccani (دکنی, dakanī or دکھنی, dakhanī;[upper-alpha 1] also known as Deccani Urdu or Deccani Hindi)[2][3][4][5] is an Indo-Aryan language spoken in the Deccan region of south-central India and the native language of the Deccani people.[6][7] The historical form of Deccani sparked the development of Urdu literature during the late-Mughal period.[8] Deccani arose as a lingua franca under the Delhi and Bahmani Sultanates, as trade and migration from the north introduced Hindustani to southern India. It later developed a literary tradition under the patronage of the Deccan Sultanates. Deccani itself came to influence Urdu and Hindi.[6][9]

The official language of the Deccan Sultanates was Persian, and due to this, Deccani has had an influence from the Persian language. In the modern era, it has mostly survived as a spoken lect and is not a literary language. Deccani differs from northern Hindustani sociolects due to archaisms retained from the medieval era, as well as a convergence with and loanwords from the Deccan's regional languages like Telugu, Tamil, Kannada, Marathi spoken in the states of Telangana, Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka and some parts of Maharashtra.[6] Deccani has been increasingly influenced by Standard Urdu, especially noticed in Hyderabadi Urdu, which serves as its formal register.

There are three primary dialects of Deccani Urdu spoken today: Hyderabadi Urdu, Mysore Urdu, and Madrasi Urdu. Hyderabadi Urdu is the closest of these dialects to Standard Urdu and the most spoken.[9]

The term "Deccani" and its variants are often used in two different contexts: a historical, obsolete one, referring to the medieval-era literary predecessor of Hindi-Urdu;[10][6] and an oral one, referring to the dialect spoken in many areas of the Deccan today.[11] Both contexts have intricate historical ties.

History[edit]

Origin[edit]

As a predecessor of modern Hindustani,[12] Deccani has its origins in the contact dialect spoken around Delhi then known as Dehlavi and now called Old Hindi. In the early 14th century, this dialect was introduced in the Deccan region through the military exploits of Alauddin Khalji.[13] In 1327 AD, Muhammad bin Tughluq shifted his Sultanate's capital from Delhi to Daulatabad (near present-day Aurangabad, Maharashtra), causing a mass migration; governors, soldiers and common people moved south, bringing the dialect with them.[14] At this time (and for the next few centuries) the cultural centres of the northern Indian subcontinent were under Persian linguistic hegemony.[15]

The Bahmani Sultanate was formed in 1347 AD with Daulatabad as its capital. This was later moved to Gulbarga and once again, in 1430, to Bidar. By this time, the dialect had acquired the name Dakhni, from the name of the region itself, and had become a lingua franca for the linguistically diverse people of the region, primarily where the Muslims had settled permanently.[16] The Bahmanids greatly promoted Persian, and did not show any notable patronage for Deccani.[17] However, their 150-year rule saw the burgeoning of a local Deccani literary culture outside the court, as religious texts were made in the language. The Sufis in the region (such as Shah Miranji) were an important vehicle of Deccani; they used it in their preachings since regional languages were more accessible (than Persian) to the general population. This era also saw production of the masnavi Kadam Rao Padam Rao by Fakhruddin Nizami in the region around Bidar. It is the earliest available manuscript of the Hindavi/Dehlavi/Deccani language, and contains loanwords from local languages such as Telugu and Marathi. Digby suggests that it was not produced in courtly settings.[15][18]

Growth[edit]

In the early 16th century, the Bahmani Sultanate splintered into the Deccan Sultanates. These were also Persianate in culture, but were characterised by an affinity towards regional languages. They are largely responsible for the development of the Deccani literary tradition, which became concentrated at Golconda and Bijapur.[19] Numerous Deccani poets were patronised in this time. According to Shaheen and Shahid, Golconda was the literary home of Asadullah Wajhi (author of Sab Ras), ibn-e-Nishati (Phulban), and Ghwasi (Tutinama). Bijapur played host to Hashmi Bijapuri, San‘ati, and Mohammed Nusrati over the years.[20]

The rulers themselves participated in these cultural developments. Muhammad Quli Qutb Shah of the Golconda Sultanate wrote poetry in Deccani, which was compiled into a Kulliyat. It is widely considered to be the earliest Urdu poetry of a secular nature.[12] Ibrahim Adil Shah II of the Bijapur Sultanate produced Kitab-e-Navras (Book of the Nine Rasas), a work of musical poetry written entirely in Deccani.[21]

Although the poets of this era were well-versed in Persian, they were characterised by a preference for indigenous cultures, and a drive to stay independent of esoteric language. As a result, the language they cultivated emphasised the Sanskritic roots of Deccani without overshadowing it, and borrowed from neighbouring languages (especially Marathi; Matthews states that Dravidian influence was much less[22]). In this regard, Shaheen and Shahid note that literary Deccani has historically been very close to spoken Deccani, unlike the northern tradition that has always exhibited diglossia.[23] Poet San'ati is a particular example of such conscious efforts to retain simplicity:[24]

Rakhīyā kām Sahnskrīt ké is mén bōl, |

I have restricted the use of Sanskrit words, |

As the language of court and culture, Persian nevertheless served as the model for poetic forms, and a good amount of Persian and Arabic vocabulary was present in the works of these writers. Hence Deccani attempted to strike a balance between Indian and Persian influences,[25][26] though it did always retain mutual intelligibility with the northern Dehlavi. This contributed to the cultivation of a distinct Deccani identity, separate from the rulers from the north; many poets proudly extolled the Deccan region and its culture.[27]

Hence, Deccani experienced cultivation into a literary language under the Sultanates, alongside its usage as a common vernacular. It also continued to be used by saints and Sufis for preaching. However, the Sultanates did not use Deccani for official purposes, preferring the prestige language Persian as well as regional languages like Marathi, Kannada, and Telugu.[28]

Decline[edit]

The Mughal conquest of the Deccan by Aurangzeb in the 17th century connected the southern regions of the subcontinent to the north, and introduced a hegemony of northern tastes. This began the decline of Deccani poetry, as literary patronage in the region decreased. The sociopolitical context of the period is reflected in Hashmi Bijapuri's poem, composed two years after the fall of Bijapur, in a time when many southern poets were pressured to change their language and style for patronage:[29]

Tujé chākrī kya tu apnīch bōl, |

Why bother about patrons, in your own words do state; |

The literary centres of the Deccan had been replaced by the capital of the Mughals, so poets migrated to Delhi for better opportunities. A notable example is that of Wali Deccani (1667–1707), who adapted his Deccani sensibilities to the northern style and produced a divan in this variety. His work inspired the Persianate poets of the north to compose in the local dialect, which in their hands became an intermediate predecessor of Hindustani known as Rekhta. This accelerated the downfall of Deccani literature, as Rekhta came to dominate the competing dialects of Mughal Hindustan.[15][30] The advent of the Asaf Jahis slowed this down, but despite their patronage of regional culture, Deccani Urdu's literary tradition died. However, the spoken variety has lived on in the Deccani Muslims, retaining some of its historical features and continuing to be influenced by the neighbouring Dravidian languages.[31][13]

Phonology[edit]

Consonants[edit]

| Labial | Dental/ Alveolar |

Retroflex | Post-alv./ Palatal |

Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | voiced | m | n | ɳ | ŋ | ||

| breathy | mʱ | nʱ | |||||

| Stop/ Affricate |

voiceless | p | t | ʈ | tʃ | k | |

| aspirated | pʰ | tʰ | ʈʰ | tʃʰ | kʰ | ||

| voiced | b | d | ɖ | dʒ | ɡ | ||

| breathy | bʱ | dʱ | ɖʱ | dʒʱ | ɡʱ | ||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | s | ʃ | x | h | |

| voiced | z | ɣ | |||||

| Trill/Tap | voiced | r | ɽ | ||||

| breathy | rʱ | ||||||

| Approximant | voiced | ʋ | l | ɭ | j | ||

| breathy | ʋʱ | lʱ | jʱ | ||||

- /h/ can be heard as either voiceless [h] or voiced [ɦ] across dialects.

- The /q/ of Urdu is merged with /x/.

Vowels[edit]

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| High | iː | uː | |

| ɪ | ʊ | ||

| Mid | e | ə | o |

| Low | aː | ||

- /e, o/ can have lax allophones of [ɛ, ɔ] when preceding consonants in medial position.

- Diphthong sounds include /əi, əe, əu, əo/.[32]

- /əi/ can be heard as [æ] after /h/.

- /əu/ can be heard as [ɔː] in initial positions.[33]

Modern era[edit]

The term Deccani today is given to a Hindustani lect spoken natively by many Muslims from Telangana, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka and Maharashtra (who are known as the Deccanis). It is considered to be the modern, spoken variety of the historical Deccani dialect, and inherits many features from it. The term Deccani distinguishes the lect from standard Urdu - however, it is commonly considered a "variety" of Urdu,[11] and often gets subsumed under this name, both by its own speakers and the official administration. The demise of the literary tradition has meant that Deccani uses standard Urdu as its formal register (i.e. for writing, news, education etc).[34]

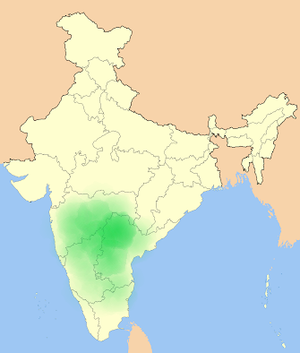

Geographical distribution[edit]

Deccani speakers centre around Hyderabad, the capital of Telangana. Deccani is also spoken in many other urban areas of the Deccan region and Mumbai, especially those with large Muslim populations such as Aurangabad, Nanded, Akola, Amravati, Bijapur, Gulbarga, Mysore and Bangalore.[35] In addition to members of the Deccani community, some Hindu Rajputs and Marathas in the Deccan speak Deccani Urdu as well, but with more hindi words.[9]

Features[edit]

Deccani is characterised by the retention of medieval-era features from Hindustani's predecessor dialects, that have disappeared in today's Hindi-Urdu. It is also distinguished by grammar and vocabulary influences from Marathi, Kannada, and Telugu, due to its prolonged use as a lingua franca in the Deccan.[34] A non-exhaustive list of its unique features, compared with standard Urdu where possible:

| Deccani | Standard Urdu equivalent | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| minje, tume (not used in Hyderabadi Urdu) | mujhe, tum | Pronouns: Singular first and second person. |

| humna, tumna (not used in Hyderabadi Urdu) | humen, tumen | |

| kane,kan | paas | |

| un, in, une, ine, | uss, iss | Pronouns: Singular third person. |

| uno, unon | uss log/woh log | Pronouns: Plural third person. |

| mereku, tereku (cognate with vernacular hindustani "mereko"

and "tereko") |

mujhko, tujhko | Possessives often used with postpositions (mera + ku, tera + ku; see Pronunciation section below for explanation of ku). |

| suffix -ān (logān, mardān) | -ān for some words (ladkiyān) and -ein, -on for others (auratein, mardon) | Used almost exclusively for nouns ending with a consonant. Standard Urdu does not have this restriction. |

| apan (used in spoken Urdu as well) | hum log | Is third person but often used in first person too. |

| suffix -ich (main idharich hoon) | hī (main idhar hī hoon) | Adds emphasis. Matthews comments that this is "probably from Marathi".[36] |

| kaiku, ki (kaiku kiya) | kyon (kyon kiya) | |

| po (main ghar po hoon) (not used in Hyderabadi Urdu) | par (main ghar par hoon) | Not an exclusive swap; both are used. |

| suffix -ingā (kal jaingā, ab karingā) | -enge (kal jayenge, ab karenge) | Plural of future tense for second and third person. |

| sangāt (Yusuf sangāt jao) | ke sāth (Yusuf ke sāth jao) | Not an exclusive swap; both are used. |

| nakko (nakko karo) | (approximately) Mat, nahin (mat karo) | From Marathi.[37] |

| kathey (āj chutti hai kathey) | Means "it seems" or "apparently".from kannada "anthe" | |

| sō (āp kharide sō ghar mere ku pasand hai) | This does not have a direct equivalent.

In standard Urdu, "jo" and "ko" are used for the same effect.[38] (vahan jo log baithe hain, unko main nahi jāntā) |

Roughly means "which/that". "āp kharide sō ghar", the house that you bought. "bade kamre me tha sō kitābān", the books that were in the big room. |

| jāko, dhoko, āko | jāke/jākar, dhoke/dhokar/, āke/ākar | Not an exclusive swap; ko, ke, and kar are all used. |

| Pronunciation | ||

| ku (Salim ku dedhey) | ko (Salim ko dedhey) | |

| jātein, khāraun, ārein, kān | jāte hain, khā raha hoon, ā rahe hain,

kahān |

Deccani drops the intervocallic 'h'. Given examples are illustrative and non-exhaustive.

The Karachi dialect of Urdu also sometimes drops "h" sounds in order to communicate faster. |

| kh ( خ ) | q ( ق ) | Deccani speakers tend to pronounce q as kh. e.g. Khuli Khutub Shah instead of Quli Qutub Shah. |

| Sources:[39][38] | ||

These features are used to different degrees among speakers, as there tends to be regional variation. Mustafa names some varieties of Deccani as "(Telugu) Dakkhini, Kannada Dakkhini, and Tamil Dakkhini", based on their influence from the dominant Dravidian language in the spoken region. He further divides Telugu Deccani into two linguistic categories, corresponding to: Andhra Pradesh, which he says has more Telugu influence; and Telangana, with more influence from standard Urdu. The latter is seen especially in Hyderabadi Urdu.[40]

Deccani's use of Urdu as a standard register, and contact with Hindustani (widespread in India), has led to some of its distinctive features disappearing. Hence many of the features in the above table are used side-by-side with those of Standard Urdu.[41]

Culture[edit]

Deccani finds a cultural core in and around Hyderabad, where the highest concentration of speakers are; Telangana is one of the only four states of India to provide "Urdu" official status. Deccani Urdu in Hyderabad has found a vehicle of expression through humour and wit, which manifests in events called "Mazahiya Mushaira", poetic symposiums with comedic themes.[42] An example of Deccani, spoken in such a context at Hyderabad:

Buzdil hai woh jo jeetey ji marne se darr gaya |

It's a coward who fears death while still alive, |

| —Ghouse Khamakha |

Additionally, the Deccani Film Industry is based in Hyderabad, and its movies are produced in Deccani, more specifically the Hyderabadi Urdu dialect.[45]

Legacy[edit]

Hindustani[edit]

Deccani is often considered a predecessor of Hindustani. The Deccani literary tradition is largely responsible for the development of modern Hindustani since contact with southern poets led to a shift in northern tastes and the development of Urdu as a literary language.[15] Deccani also imparted the practice of writing the local vernacular in the Perso-Arabic script, which eventually became the standard practice for Urdu all over the Indian subcontinent.[46]

See also[edit]

- Hyderabadi Urdu

- Urdu in Aurangabad

- Nawayathi (Kumta, Honnavar, Bhatkal)

- Deccani Muslims

- Deccani Film Industry

- Deccani Marathi, which goes by the same names

References[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ↑ Deccani is spelled variously as Dakni, Dakani, Dakhni, Dakhani, Dakhini, Dakkhani, Dakkhini and Dakkani

Citations[edit]

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Dakhini (Urdu)". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History. Search this book on

- ↑ Khan, Abdul Jamil (2006). Urdu/Hindi: An Artificial Divide: African Heritage, Mesopotamian Roots, Indian Culture & Britiah Colonialism. Algora Publishing. ISBN 978-0-87586-438-9. Search this book on

- ↑ Azam, Kousar J. (9 August 2017). Languages and Literary Cultures in Hyderabad. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-351-39399-7. Search this book on

- ↑ Verma, Dinesh Chandra (1990). Social, Economic, and Cultural History of Bijapur. Idarah-i Adabiyat-i Delli. p. 141.

Deccani Hindi is indebted for its development to the Muslim poets and writers chiefly belonging to the kingdom of Bijapur.

Search this book on

- ↑ Arun, Vidya Bhaskar (1961). A Comparative Phonology of Hindi and Panjabi. Panjabi Sahitya Akademi. p. xii.

The Deccani Hindi Poetry in its earlier phase was not so much Persianised as it became later.

Search this book on

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Kama Maclean (26 September 2021). "Language and Cinema: Schisms in the Representation of Hyderabad". Retrieved 12 February 2024.

The Deccani language developed between the fourteenth and seventeenth centuries in the Deccan—it is known to be an old form of Hindi and Urdu. Deccani was influenced by the other languages of the region, that is, it borrowed some words from Telugu, Kannada and Marathi. Deccani was known as the language from the South and it later travelled to the north of India and influenced Khari Boli. It also had a significant influence on the development of Hindi and Urdu.

- ↑ Emeneau, Murray B.; Fergusson, Charles A. (2016-11-21). Linguistics in South Asia. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. ISBN 978-3-11-081950-2. Search this book on

- ↑ Imam, Syeda (2008-05-14). The Untold Charminar. Penguin UK. ISBN 978-81-8475-971-6. Search this book on

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 "Urdu-Phonology and Morphology" (PDF).

- ↑ Rahman 2011, p. 22.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Rahman 2011, p. 4.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Rahman 2011, p. 27.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Mustafa 2008, p. 185.

- ↑ Dua 2012, p. 383.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 Matthews, David. "Urdu". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Archived from the original on 29 April 2011. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ A History of the Freedom Movement:Being the Story of Muslim Struggle for the Freedom of Hind-Pakistan, 1707-1947 · Volume 3, Issue 2. Pakistan Historical Society. 1957. Search this book on

- ↑ Schmidt, Ruth L. (1981). Dakhini Urdu : History and Structure. New Delhi. pp. 3 & 6. Search this book on

- ↑ Digby, Simon (2004). "Before Timur Came: Provincialization of the Delhi Sultanate through the Fourteenth Century". Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient. 47 (3): 333–335. doi:10.1163/1568520041974657. JSTOR 25165052 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ Shaheen & Shahid 2018, p. 100.

- ↑ Shaheen & Shahid 2018, p. 124.

- ↑ Matthews, David J. (1993). "Eighty Years of Dakani Scholarship". The Annual of Urdu Studies. 9: 92–93.

- ↑ Matthews 1976, p. 170.

- ↑ Shaheen & Shahid 2018, p. 116.

- ↑ Shaheen & Shahid 2018, p. 101-103.

- ↑ Shaheen & Shahid 2018, p. 103-104.

- ↑ Matthews 1976, p. 283.

- ↑ Shaheen & Shahid 2018, p. 106-108.

- ↑ Eaton, Richard (2005). A Social History of the Deccan, 1300–1761. The New Cambridge History of India. Cambridge University Press. pp. 142–144. ISBN 9780521254847. Search this book on

- ↑ Shaheen & Shahid 2018, p. 116 & 143.

- ↑ Faruqi, Shamsur Rahman (2003). Pollock, Sheldon, ed. Urdu Literary Culture, Part 1. Literary Cultures in History. Reconstructions from South Asia. University of California Press. pp. 837 & 839. ISBN 0520228219. Search this book on

- ↑ Shaheen & Shahid 2018, p. 118-119.

- ↑ Mustafa, Khateeb S. (1985). A descriptive study of Dakhni Urdu as spoken in the Chittoor District, A. P. Aligarh: Aligarh Muslim University. Search this book on

- ↑ Schmidt, Ruth L. (1981). Dakhini Urdu : history and structure. Bahri, New Delhi. Search this book on

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Matthews 1976, p. 221-222.

- ↑ Masica, Colin P. (1993). The Indo-Aryan Languages. Cambridge University Press. pp. 22 & 426. Search this book on

- ↑ Matthews 1976, p. 74.

- ↑ Matthews 1976, p. 215.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Masica, Colin P. (1993). The Indo-Aryan Languages. Cambridge University Press. p. 413. ISBN 9780521299442. Search this book on

- ↑ Matthews 1976, p. 222-224.

- ↑ Mustafa 2008, p. 186.

- ↑ Matthews 1976, p. 179.

- ↑ Sharma, R.S. (2018). Azam, Kousar J, ed. A Tentative Paradigm for the Study of Languages and Literary Cultures in Hyderabad City. Languages and Literary Cultures in Hyderabad. Routledge. pp. 32–33. ISBN 9781351393997. Search this book on

- ↑ "Ghouse Khamakhan (Part 1): Dakhani Mazahiya Mushaira". YouTube. Siasat Daily. 19 March 2011. Archived from the original on 2021-12-12. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ "A Tongue Tied: The Story of Dakhani". Archived from the original on 6 April 2009. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ Mumtaz, Roase. "Deccanwood: An Indian film industry taking on Bollywood". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 2018-02-23.

- ↑ Dua 2012, pp. 383–384.

Bibliography[edit]

- Dua, Hans R. (2012), "Hindi-Urdu as a pluricentric language", in Michael Clyne, Pluricentric Languages: Differing Norms in Different Nations, Walter de Gruyter, ISBN 978-3-11-088814-0

- Rahman, Tariq (2011), From Hindi to Urdu: A Social and Political History (PDF), Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-906313-0, archived from the original (PDF) on 10 October 2014 Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - Mustafa, K.S (2008), "Dakkhni", in Prakāśaṃ, Vennelakaṇṭi, Encyclopaedia of the Linguistic Sciences: Issues and Theories, Allied Publishers, pp. 185–186, ISBN 978-1139465502

- Shaheen, Shagufta; Shahid, Sajjad (2018), Azam, Kousar J, ed., "The Unique Literary Traditions of Dakhnī", Languages and Literary Cultures in Hyderabad, Routledge, ISBN 9781351393997

- Sharma, Ram (1964), दक्खिनी हिन्दी का उद्भव और विकास (PDF) (in Hindi), Allahabad: Hindi Sahitya SammelanCS1 maint: Unrecognized language (link)

- Matthews, David J. (1976). Dakani Language and Literature (Thesis). SOAS University of London.

Further reading[edit]

- Gricourt, Marguerite (2015). "Dakhinī Urdū". In Fleet, Kate; Krämer, Gudrun; Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John; Rowson, Everett. Encyclopaedia of Islam, THREE. Brill Online. ISSN 1873-9830.

- Urban culture of Medieval Deccan (1300 AD-1650 AD)

- Bulletin of the Deccan College Post-Graduate and Research Institute, Volume 22 (1963)

- Deccani Painting by Mark Zebrowski

- Mohammed Abdul Muid Khan (1963). "The Arabian Poets of Golconda". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. Bombay University. 96 (2): 137–138. doi:10.1017/S0035869X00123299. Unknown parameter

|s2cid=ignored (help)