Amitabh Bachchan

| Amitabh Bachchan | |

|---|---|

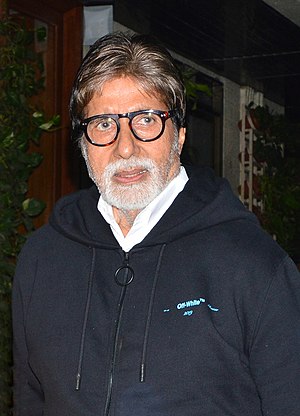

Indian actor Amitabh Bachchan.jpg Indian actor Amitabh Bachchan.jpg Bachchan in November 2018 | |

| Born | Inquilaab Srivastava[1] 11 October 1942 Allahabad, United Provinces, British India (present-day Uttar Pradesh, India) |

| 🏳️ Nationality | Indian |

| Other names | Angry Young Man, Shahenshah of Bollywood, Star of the Millennium, and Big B |

| 🎓 Alma mater | Sherwood College, Nainital Kirori Mal College, Delhi University[2] |

| 💼 Occupation |

|

| 📆 Years active | 1969–present |

| 💰 Net worth | $400 million (2020)[3] |

| 👩 Spouse(s) | Jaya Bhaduri (m. 1973) |

| 👶 Children | |

| 👴 👵 Parents |

|

| Family | See Bachchan family |

| 🏅 Awards | Full List |

| Honours | Dadasaheb Phalke Award (2019) Padma Vibhushan (2015) Padma Bhushan (2001) Padma Shri |

| 🌐 Website | Official blog |

| Signature | |

| |

Amitabh Bachchan (pronounced [əmɪˈtaːbʱ ˈbətʃːən]; born Inquilaab Srivastava;[1] 11 October 1942[4]) is an Indian film actor, film producer, television host, occasional playback singer and former politician. He first gained popularity in the early 1970s for films such as Zanjeer, Deewaar and Sholay, and was dubbed India's "angry young man" for his on-screen roles in Bollywood. Referred to as the Shahenshah of Bollywood (in reference to his 1988 film Shahenshah), Sadi ka Mahanayak (Hindi for, "Greatest actor of the century"), Star of the Millennium, or Big B,[5][6][7] he has since appeared in over 200 Indian films in a career spanning more than five decades.[8] Bachchan is widely regarded as one of the greatest and most influential actors in the history of Indian cinema as well as world cinema.[9][10][11][12][13]

He was the most dominant actor in the Indian movie scene during the 1970s–1980s, with the French director François Truffaut calling him a "one-man industry".[14] Beyond the Indian subcontinent, he also has a large overseas following in markets including Africa (especially South Africa and Mauritius), the Middle East (especially Egypt), the United Kingdom, Russia, the Caribbean (especially Guyana, Suriname, and Trinidad and Tobago), Oceania (especially Fiji, Australia, and New Zealand) and parts of the United States.[15][11][16][17][18]

Bachchan has won numerous accolades in his career, including four National Film Awards as Best Actor, Dadasaheb Phalke Award as lifetime achievement award and many awards at international film festivals and award ceremonies. He has won fifteen Filmfare Awards and is the most nominated performer in any major acting category at Filmfare, with 41 nominations overall. In addition to acting, Bachchan has worked as a playback singer, film producer and television presenter. He has hosted several seasons of the game show Kaun Banega Crorepati, India's version of the game show franchise, Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?. He also entered politics for a time in the 1980s.

The Government of India honoured him with the Padma Shri in 1984, the Padma Bhushan in 2001 and the Padma Vibhushan in 2015 for his contributions to the arts. The Government of France honoured him with its highest civilian honour, Knight of the Legion of Honour, in 2007 for his exceptional career in the world of cinema and beyond. Bachchan also made an appearance in a Hollywood film, Baz Luhrmann's The Great Gatsby (2013), in which he played a non-Indian Jewish character, Meyer Wolfsheim.

Early life and family[edit]

Bachchan was born in Allahabad.[19] His ancestors on his father's side came from a village called Babupatti, in the Raniganj tehsil, in the Pratapgarh district, in the present-day state of Uttar Pradesh, in India.[20] His mother, Teji Bachchan, was a social activist and Punjabi Sikh woman from Lyallpur, Punjab, British India (present-day Faisalabad, Punjab, Pakistan).[21] His father, Harivansh Rai Bachchan was an Awadhi Hindu. His father was a poet, who was fluent in Awadhi[21], Hindi and Urdu.[22]

Bachchan was initially named Inquilaab, inspired by the phrase Inquilab Zindabad (which translates into English as "Long live the revolution") popularly used during the Indian independence struggle. However, at the suggestion of fellow poet Sumitranandan Pant, Harivansh Rai changed the boy's name to Amitabh, which, according to a The Times of India article, means "the light that will never die".[23][lower-alpha 1] Although his surname was Shrivastava, Amitabh's father had adopted the pen name Bachchan ("child-like" in colloquial Hindi), under which he published all of his works.[24] It is with this last name that Amitabh debuted in films and for all other practical purposes, Bachchan has become the surname for all of his immediate family.[25] Bachchan's father died in 2003, and his mother in 2007.[26]

Bachchan is an alumnus of Sherwood College, Nainital. He later attended Kirori Mal College, University of Delhi.[27] He has a younger brother, Ajitabh. His mother had a keen interest in theatre and was offered a feature film role, but she preferred her domestic duties. Teji had some influence in Amitabh Bachchan's choice of career because she always insisted that he should "take the centre stage".[28]

The actor who Bachchan credits as having the biggest impact on him was Dilip Kumar. In particular, Bachchan says he learnt more about acting from Kumar's Gunga Jumna (1961) than he did from any other film. Bachchan was particularly impressed by Kumar's mastery of Awadhi, expressing awe and surprise as to how “a man who’s not from Allahabad and Uttar Pradesh” could accurately express all the nuances of Awadhi.[29] Bachchan adapted Kumar's style, reinterpreting it in a contemporary urban context,[30] adopting some of Kumar's method acting,[31] and sharpening the intensity, resulting in his famous "angry young man" persona.[32]

He is married to actress Jaya Bhaduri.[33]

Acting career[edit]

Early career (1969–1972)[edit]

Bachchan made his film debut in 1969, as a voice narrator in Mrinal Sen's National Award-winning film Bhuvan Shome.[34] His first acting role was as one of the seven protagonists in the film Saat Hindustani,[35] directed by Khwaja Ahmad Abbas and featuring Utpal Dutt, Anwar Ali (brother of comedian Mehmood), Madhu and Jalal Agha.[36][37]

Anand (1971) followed, in which Bachchan starred alongside Rajesh Khanna. His role as a doctor with a cynical view of life garnered Bachchan his first Filmfare Best Supporting Actor award. He then played his first antagonist role as an infatuated lover-turned-murderer in Parwana (1971). Following Parwana were several films including Reshma Aur Shera (1971). During this time, he made a guest appearance in the film Guddi which starred his future wife Jaya Bhaduri. He narrated part of the film Bawarchi. In 1972 he made an appearance in the road action comedy Bombay to Goa directed by S. Ramanathan which was moderately successful.[38][39][40] Many of Bachchan's films during this early period did not do well, but that was about to change.[41] His only film with Mala Sinha, Sanjog (1972) was also a box office success.[42]

Rise to stardom (1973–1974)[edit]

Bachchan was struggling, seen as a "failed newcomer" who, by the age of 30, had twelve flops and only two hits (as a lead in Bombay to Goa and supporting role in Anand). Bachchan was soon discovered by screenwriter duo Salim-Javed, consisting of Salim Khan and Javed Akhtar.[43] Salim Khan wrote the story, screenplay and script of Zanjeer (1973), and conceived the "angry young man" persona of the lead role. Javed Akhtar came on board as co-writer,[44] and Prakash Mehra, who saw the script as potentially groundbreaking, as the film's director. However, they were struggling to find an actor for the lead "angry young man" role; it was turned down by a number of actors, owing to it going against the "romantic hero" image dominant in the industry at the time.[43] Salim-Javed soon discovered Bachchan and "saw his talent, which most makers didn't. He was exceptional, a genius actor who was in films that weren't good."[45] According to Salim Khan, they "strongly felt that Amitabh was the ideal casting for Zanjeer".[43] Salim Khan introduced Bachchan to Prakash Mehra,[44] and Salim-Javed insisted that Bachchan be cast for the role.[43]

Zanjeer was a crime film with violent action,[43] in sharp contrast to the romantically themed films that had generally preceded it, and it established Amitabh in a new persona—the "angry young man" of Bollywood cinema.[46] He earned his first Filmfare Award nomination for Best Actor, with Filmfare later considering this one of the most iconic performances of Bollywood history.[41] The film was a huge success and one of the highest-grossing films of that year, breaking Bachchan's dry spell at the box office and making him a star.[47] It was the first of many collaborations between Salim-Javed and Amitabh Bachchan; Salim-Javed wrote many of their subsequent scripts with Bachchan in mind for the lead role, and insisted on him being cast for their later films, including blockbusters such as Deewaar (1975) and Sholay (1975).[45] Salim Khan also introduced Bachchan to director Manmohan Desai with whom he formed a long and successful association, alongside Prakash Mehra and Yash Chopra.[44]

Eventually, Bachchan became one of the most successful leading men of the film industry. Bachchan's portrayal of the wronged hero fighting a crooked system and circumstances of deprivation in films like Zanjeer, Deeewar, Trishul, Kaala Patthar and Shakti resonated with the masses of the time, especially the youth who harboured a simmering discontent owing to social ills such as poverty, hunger, unemployment, corruption, social inequality and the brutal excesses of The Emergency. This led to Bachchan being dubbed as the "angry young man", a journalistic catchphrase which became a metaphor for the dormant rage, frustration, restlessness, sense of rebellion and anti-establishment disposition of an entire generation, prevalent in 1970s India.[48][49][50][51]

The year 1973 was also when he married Jaya, and around this time they appeared in several films together: not only Zanjeer but also subsequent films such as Abhimaan, which was released only a month after their marriage and was also successful at the box office. Later, Bachchan played the role of Vikram, once again along with Rajesh Khanna, in the film Namak Haraam, a social drama directed by Hrishikesh Mukherjee and scripted by Biresh Chatterjee addressing themes of friendship. His supporting role won him his second Filmfare Best Supporting Actor award.[52]

In 1974, Bachchan made several guest appearances in films such as Kunwara Baap and Dost, before playing a supporting role in Roti Kapda Aur Makaan. The film, directed and written by Manoj Kumar, addressed themes of honesty in the face of oppression and financial and emotional hardship and was the top-earning film of 1974. Bachchan then played the leading role in the film Majboor. The film was a success at the box office.[53]

Successful career (1975–1988)[edit]

In 1975, he starred in a variety of film genres, from the comedy Chupke Chupke and the crime drama Faraar to the romantic drama Mili. This was also the year in which Bachchan starred in two films regarded as important in Hindi cinema history, both written by Salim-Javed, who again insisted on casting Bachchan.[45] The first was Deewaar, directed by Yash Chopra, where he worked with Shashi Kapoor, Nirupa Roy, Parveen Babi, and Neetu Singh, and earned another Filmfare nomination for Best Actor. The film became a major hit at the box office in 1975, ranking in at number four.[54] Indiatimes Movies ranks Deewaar amongst the Top 25 Must See Bollywood Films.[55] The other, released on 15 August 1975, was Sholay, which became the highest-grossing film ever in India at the time,[56] in which Bachchan played the role of Jaidev. Deewaar and Sholay are often credited with exalting Bachchan to the heights of superstardom, two years after he became a star with Zanjeer, and consolidating his domination of the industry throughout the 1970s and 1980s.[57][58] In 1999, BBC India declared Sholay the "Film of the Millennium" and, like Deewar, it has been cited by Indiatimes Movies as amongst the Top 25 Must See Bollywood Films.[55] In that same year, the judges of the 50th annual Filmfare Awards awarded it with the special distinction award called the Filmfare Best Film of 50 Years.

In 1976, he was cast by Yash Chopra in the romantic family drama Kabhie Kabhie. Bachchan starred as a young poet, Amit Malhotra, who falls deeply in love with a beautiful young girl named Pooja (Rakhee Gulzar) who ends up marrying someone else (Shashi Kapoor). The film was notable for portraying Bachchan as a romantic hero, a far cry from his "angry young man" roles like Zanjeer and Deewar. The film evoked a favourable response from critics and audiences alike. Bachchan was again nominated for the Filmfare Best Actor Award for his role in the film. That same year he played a double role in the hit Adalat as father and son. In 1977, he won his first Filmfare Best Actor Award for his performance in Amar Akbar Anthony, in which he played the third lead opposite Vinod Khanna and Rishi Kapoor as Anthony Gonsalves. The film was the highest-grossing film of that year. His other successes that year include Parvarish and Khoon Pasina.[59]

He once again resumed double roles in films such as Kasme Vaade (1978) as Amit and Shankar and Don (1978) playing the characters of Don, a leader of an underworld gang and his look-alike Vijay. His performance won him his second Filmfare Best Actor Award. He also gave towering performances in Yash Chopra's Trishul and Prakash Mehra's Muqaddar Ka Sikandar both of which earned him further Filmfare Best Actor nominations. 1978 is arguably considered his most successful year at the box office since all of his six releases the same year, namely Muqaddar Ka Sikandar, Trishul, Don, Kasme Vaade, Ganga Ki Saugandh and Besharam were massive successes, the former three being the consecutive highest-grossing films of the year, remarkably releasing within a couple of months of each other, a rare feat in Indian cinema.[60][61][62]

In 1979, Bachchan starred in Suhaag which was the highest earning film of that year. In the same year he also enjoyed critical acclaim and commercial success with films like Mr. Natwarlal, Kaala Patthar, The Great Gambler and Manzil. Amitabh was required to use his singing voice for the first time in a song from the film Mr. Natwarlal in which he starred with Rekha. Bachchan's performance in the film saw him nominated for both the Filmfare Best Actor Award and the Filmfare Award for Best Male Playback Singer. He also received Best Actor nomination for Kaala Patthar and then went on to be nominated again in 1980 for the Raj Khosla directed film Dostana, in which he starred opposite Shatrughan Sinha and Zeenat Aman. Dostana proved to be the top-grossing film of 1980.[63] In 1981, he starred in Yash Chopra's melodrama film Silsila, where he starred alongside his wife Jaya and also Rekha. Other successful films of this period include Shaan (1980), Ram Balram (1980), Naseeb (1981), Lawaaris (1981), Kaalia (1981), Yaarana (1981), Barsaat Ki Ek Raat (1981) and Shakti (1982), also starring Dilip Kumar.

In 1982, he played double roles in the musical Satte Pe Satta and action drama Desh Premee which succeeded at the box office along with mega hits like action comedy Namak Halaal, action drama Khud-Daar and the critically acclaimed drama Bemisal.[64] In 1983, he played a triple role in Mahaan which was not as successful as his previous films.[65] Other releases during that year included Nastik, Andha Kanoon (in which he had an extended guest appearance) which were hits and Pukar was an average grosser[66] During a stint in politics from 1984 to 1987, his completed films Mard (1985) and Aakhree Raasta (1986) were released and were major hits.[67]

Coolie injury

On 26 July 1982, while filming Coolie, in the University Campus in Bangalore, Bachchan suffered a near-fatal intestinal injury during the filming of a fight scene with co-actor Puneet Issar.[68] Bachchan was performing his own stunts in the film and one scene required him to fall onto a table and then on the ground. However, as he jumped towards the table, the corner of the table struck his abdomen, resulting in a splenic rupture from which he lost a significant amount of blood. He required an emergency splenectomy and remained critically ill in hospital for many months, at times close to death. The overwhelming public response included prayers in temples and offers to sacrifice limbs to save him, while later, there were long queues of well-wishing fans outside the hospital where he was recuperating.[69]

Nevertheless, he resumed filming later that year after a long period of recuperation. The film was released in 1983, and partly due to the huge publicity of Bachchan's accident, the film was a box office success and the top-grossing film of that year.[70]

The director, Manmohan Desai, altered the ending of Coolie after Bachchan's accident. Bachchan's character was originally intended to have been killed off but after the change of script, the character lived in the end. It would have been inappropriate, said Desai, for the man who had just fended off death in real life to be killed on screen. Also, in the released film the footage of the fight scene is frozen at the critical moment, and a caption appears onscreen marking this as the instant of the actor's injury and the ensuing publicity of the accident.[71]

Later, he was diagnosed with Myasthenia gravis. His illness made him feel weak both mentally and physically and he decided to quit films and venture into politics. At this time he became pessimistic, expressing concern with how a new film would be received, and stating before every release, "Yeh film to flop hogi!" ("This film will flop").[72]

Career fluctuations and retirement (1988–1992)[edit]

After a three-year stint in politics from 1984 to 1987, Bachchan returned to films in 1988, playing the title role in Shahenshah, which was a box office success.[73] After the success of his comeback film however, his star power began to wane as all of his subsequent films like Jaadugar, Toofan and Main Azaad Hoon (all released in 1989) failed at the box office. Successes during this period like the crime drama Aaj Ka Arjun (1990) and action crime drama Hum (1991), for which he won his third Filmfare Best Actor Award, looked like they might reverse the trend, but this momentum was short-lived and his string of box office failures continued.[74][75] Notably, despite the lack of hits, it was during this era that Bachchan won his first National Film Award for Best Actor for his performance as a Mafia don in the 1990 cult film Agneepath. These years would see his last on-screen appearances for some time. After the release of the critically acclaimed epic Khuda Gawah in 1992, Bachchan went into semi-retirement for five years. With the exception of the delayed release of Insaniyat (1994), which was also a box office failure, Bachchan did not appear in any new releases for five years.[76]

Productions and acting comeback (1996–1999)[edit]

Bachchan turned producer during his temporary retirement period, setting up Amitabh Bachchan Corporation, Ltd. (ABCL) in 1996. ABCL's strategy was to introduce products and services covering an entire cross-section of India's entertainment industry. ABCL's operations were mainstream commercial film production and distribution, audio cassettes and video discs, production and marketing of television software, and celebrity and event management.[77] Soon after the company was launched in 1996, the first film it produced was Tere Mere Sapne, which was a moderate success and launched the careers of actors like Arshad Warsi and southern film star Simran.[78]

In 1997, Bachchan attempted to make his acting comeback with the film Mrityudata, produced by ABCL. Though Mrityudaata attempted to reprise Bachchan's earlier success as an action hero, the film was a failure both financially and critically.[79] ABCL was the main sponsor of the 1996 Miss World beauty pageant, Bangalore, but lost millions. The fiasco and the consequent legal battles surrounding ABCL and various entities after the event, coupled with the fact that ABCL was reported to have overpaid most of its top-level managers, eventually led to its financial and operational collapse in 1997.[80][81] The company went into administration and was later declared a failed company by the Indian Industries board. The Bombay high court, in April 1999, restrained Bachchan from selling off his Bombay bungalow 'Prateeksha' and two flats till the pending loan recovery cases of Canara Bank were disposed of. Bachchan had, however, pleaded that he had mortgaged his bungalow to raise funds for his company.[82]

Bachchan attempted to revive his acting career, and eventually had commercial success with Bade Miyan Chote Miyan (1998) and Major Saab (1998),[83] and received positive reviews for Sooryavansham (1999),[84] but other films such as Lal Baadshah (1999) and Hindustan Ki Kasam (1999) were box office failures.[85]

Return to prominence (2000–present)[edit]

In 2000, Amitabh Bachchan appeared in Yash Chopra's box-office hit, Mohabbatein, directed by Aditya Chopra. He played a stern, elder figure who rivalled the character of Shahrukh Khan. His role won him his third Filmfare Best Supporting Actor Award. Other hits followed, with Bachchan appearing as an older family patriarch in Ek Rishtaa: The Bond of Love (2001), Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham... (2001) and Baghban (2003). As an actor, he continued to perform in a range of characters, receiving critical praise for his performances in Aks (2001), Aankhen (2002), Kaante (2002), Khakee (2004) and Dev (2004). His performance in Aks won him his first Filmfare Critics Award for Best Actor.

One project that did particularly well for Bachchan was Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Black (2005). The film starred Bachchan as an ageing teacher of a deaf-blind girl and followed their relationship. His performance was unanimously praised by critics and audiences and won him his second National Film Award for Best Actor, his fourth Filmfare Best Actor Award and his second Filmfare Critics Award for Best Actor. Taking advantage of this resurgence, Amitabh began endorsing a variety of products and services, appearing in many television and billboard advertisements. In 2005 and 2006, he starred with his son Abhishek in the films Bunty Aur Babli (2005), the Godfather tribute Sarkar (2005), and Kabhi Alvida Naa Kehna (2006). All of them were successful at the box office.[86][87] His later releases in 2006 and early 2007 were Baabul (2006),[88] Ekalavya and Nishabd (2007), which failed to do well at the box office but his performances in each of them were praised by critics.[89]

In May 2007, two of his films: the romantic comedy Cheeni Kum and the multi-starrer action drama Shootout at Lokhandwala were released. Shootout at Lokhandwala did well at the box office and was declared a hit in India, while Cheeni Kum picked up after a slow start and was a success.[90][91][92][93] A remake of his biggest hit, Sholay (1975), entitled Ram Gopal Varma Ki Aag, released in August of that same year and proved to be a major commercial failure in addition to its poor critical reception.[93] The year also marked Bachchan's first appearance in an English-language film, Rituparno Ghosh's The Last Lear, co-starring Arjun Rampal and Preity Zinta. The film premiered at the 2007 Toronto International Film Festival on 9 September 2007. He received positive reviews from critics who hailed his performance as his best ever since Black.[94] Bachchan was slated to play a supporting role in his first international film, Shantaram, directed by Mira Nair and starring Hollywood actor Johnny Depp in the lead. The film was due to begin filming in February 2008 but due to the writer's strike, was pushed to September 2008.[95] The film is currently "shelved" indefinitely.[96]

Vivek Sharma's Bhoothnath, in which he plays the title role as a ghost, was released on 9 May 2008. Sarkar Raj, the sequel of the 2005 film Sarkar, released in June 2008 and received a positive response at the box office. Paa, which released at the end of 2009 was a highly anticipated project as it saw him playing his own son Abhishek's Progeria-affected 13-year-old son, and it opened to favourable reviews, particularly towards Bachchan's performance and was one of the top-grossing films of 2009.[97] It won him his third National Film Award for Best Actor and fifth Filmfare Best Actor Award. In 2010, he debuted in Malayalam film through Kandahar, directed by Major Ravi and co-starring Mohanlal.[98] The film was based on the hijacking incident of the Indian Airlines Flight 814.[99] Bachchan declined any remuneration for this film.[100]

In 2013 he made his Hollywood debut in The Great Gatsby making a special appearance opposite Leonardo DiCaprio and Tobey Maguire. In 2014, he played the role of the friendly ghost in the sequel Bhoothnath Returns. The next year, he played the role of a grumpy father suffering from chronic constipation in the critically acclaimed Piku which was also one of the biggest hits of 2015.[101][102][103] A review in Daily News and Analysis (DNA) summarised Bachchan's performance as "The heart and soul of Piku clearly belong to Amitabh Bachchan who is in his elements. His performance in Piku, without doubt, finds a place among the top 10 in his illustrious career."[104] Rachel Saltz wrote for The New York Times, "Piku," an offbeat Hindi comedy, would have you contemplate the intestines and mortality of one Bhashkor Banerji and the actor who plays him, Amitabh Bachchan. Bhashkor's life and conversation may revolve around his constipation and fussy hypochondria, but there's no mistaking the scene-stealing energy that Mr. Bachchan, India's erstwhile Angry Young Man, musters for his new role of Cranky Old Man."[105] Well known Indian critic Rajeev Masand wrote on his website, "Bachchan is pretty terrific as Bhashkor, who reminds you of that oddball uncle that you nevertheless have a soft spot for. He bickers with the maids, harrows his hapless helper, and expects that Piku stay unmarried so she can attend to him. At one point, to ward off a possible suitor, he casually mentions that his daughter isn't a virgin; that she's financially independent and sexually independent too. Bachchan embraces the character's many idiosyncrasies, never once slipping into caricature while all along delivering big laughs thanks to his spot-on comic timing.[106] The Guardian summed up, "Bachchan seizes upon his cranky character part, making Bashkor as garrulously funny in his theories on caste and marriage as his system is backed-up."[107] The performance won Bachchan his fourth National Film Award for Best Actor and his third Filmfare Critics Award for Best Actor.

In 2016, he appeared in the women-centric courtroom drama film Pink which was highly praised by critics and with an increasingly good word of mouth, was a resounding success at the domestic and overseas box office.[108][109][110][111][112] Bachchan's performance in the film received acclaim. According to Raja Sen of Rediff.com, "Amitabh Bachchan, a retired lawyer suffering from bipolar disorder, takes up cudgels on behalf of the girls, delivering courtroom blows with pugilistic grace. Like we know from Prakash Mehra movies, into each life some Bachchan must fall. The girls hang on to him with incredulous desperation, and he bats for them with all he has. At one point Meenal hangs by Bachchan's elbow, words entirely unnecessary. Bachchan towers through Pink – the way he bellows "et cetera" is alone worth having the heavy-hitter at play—but there are softer moments like one where he appears to have dozed off in court, or where he lays his head by his convalescent wife's bedside and needs his hair ruffled and his conviction validated."[113] Writing for Hindustan Times, noted film critic and author Anupama Chopra said of Bachchan's performance, "A special salute to Amitabh Bachchan, who imbues his character with a tragic majesty. Bachchan towers in every sense, but without a hint of showboating.[109] Meena Iyer of The Times of India wrote, "The performances are pitch-perfect with Bachchan leading the way.[114] Writing for NDTV, Troy Ribeiro of Indo-Asian News Service (IANS) stated, 'Amitabh Bachchan as Deepak Sehgall, the aged defence lawyer, shines as always, in a restrained, but powerful performance. His histrionics come primarily in the form of his well-modulated baritone, conveying his emotions and of course, from the well-written lines.'[115] Mike McCahill of The Guardian remarked, "Among an electric ensemble, Tapsee Pannu, Kirti Kulhari and Andrea Tariang give unwavering voice to the girls’ struggles; Amitabh Bachchan brings his moral authority to bear as their sole legal ally.[116]

In 2017, he appeared in the third instalment of the Sarkar film series: Ram Gopal Varma's Sarkar 3. That year, he started filming for the swashbuckling action adventure film Thugs Of Hindostan with Aamir Khan, Katrina Kaif and Fatima Sana Shaikh which released in November 2018.[117] He co-starred with Rishi Kapoor in 102 Not Out, a comedy-drama film directed by Umesh Shukla based on a Gujarati play of the same name written by Saumya Joshi.[118][119][120] This film released in May 2018 and reunited him with Kapoor onscreen after a gap of twenty-seven years. In October 2017, it was announced that Bachchan will appear in Ayan Mukerji's Brahmastra, alongside Ranbir Kapoor and Alia Bhatt.[121]

Other work[edit]

Politics[edit]

In 1984, Bachchan took a break from acting and briefly entered politics in support of a long-time family friend, Rajiv Gandhi. He contested Allahabad's seat for the 8th Lok Sabha against H. N. Bahuguna, former Chief Minister of Uttar Pradesh and won by one of the highest victory margins in general election history (68.2% of the vote).[122] His political career, however, was short-lived: he resigned after three years, calling politics a cesspool. The resignation followed the implication of Bachchan and his brother in the "Bofors scandal" by a newspaper, which he vowed to take to court.[123] Bachchan was eventually found not guilty of involvement in the ordeal. He was framed in the scam and falsely alleged. This was cleared by Swedish police chief Sten Lindstrom.[124]

His old friend, Amar Singh, helped him during the financial crisis caused by the failure of his company, ABCL. Thereafter Bachchan started supporting the Samajwadi Party, the political party to which Amar Singh belonged. Furthermore, Jaya Bachchan joined the Samajwadi Party and represented the party as an MP in the Rajya Sabha.[125] Bachchan has continued to do favours for the Samajwadi Party, including appearing in advertisements and political campaigns. These activities have recently got him into trouble in the Indian courts for false claims after a previous incident of submission of legal papers by him, stating that he is a farmer.[126]

A 15-year press ban against Bachchan was imposed during his peak acting years by Stardust and some of the other film magazines. In defence, Bachchan claimed to have banned the press from entering his sets until late 1989.[127]

Bachchan has been accused of using the slogan "blood for blood" in the context of the 1984 anti-Sikh riots. Bachchan has denied the allegation.[128] In October 2014, Bachchan was summoned by a court in Los Angeles for "allegedly instigating violence against the Sikh community".[129][130][131][132]

Television appearances[edit]

In 2000, Bachchan hosted the first season of Kaun Banega Crorepati (KBC), the Indian adaptation of the British television game show, Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?. The show was well received.[133] A second season followed in 2005 but its run was cut short by Star Plus when Bachchan fell ill in 2006.[134]

In 2009, Bachchan hosted the third season of the reality show Bigg Boss.[135]

In 2010, Bachchan hosted the fourth season of KBC.[136] The fifth season started on 15 August 2011 and ended on 17 November 2011. The show became a massive hit with audiences and broke many TRP Records. CNN IBN awarded Indian of the Year- Entertainment to Team KBC and Bachchan. The Show also grabbed all the major Awards for its category.[137] Bachchan continued to host KBC until 2017.

The sixth season was also hosted by Bachchan, commencing on 7 September 2012, broadcast on Sony TV and received the highest number of viewers thus far.[138]

In 2014, he debuted in the fictional Sony Entertainment Television TV series titled Yudh playing the lead role of a businessman battling both his personal and professional life.[139]

Voice-acting[edit]

Bachchan is known for his deep, baritone voice. He has been a narrator, a playback singer, and presenter for numerous programmes.[140][141][142] Renowned film director Satyajit Ray was so impressed with Bachchan's voice that he decided to use Bachchan as the narrator in his 1977 film Shatranj Ke Khilari (The Chess Players).[143] Bachchan lent his voice as a narrator to the 2001 movie Lagaan which was a super hit.[144] In 2005, Bachchan lent his voice to the Oscar-winning French documentary March of the Penguins, directed by Luc Jacquet.[145]

He also has done voice-over work for the following movies:[146][147][148]

- Bhuvan Shome (1969)[149]

- Bawarchi (1972)

- Balika Badhu (1975)

- Tere Mere Sapne (1996)

- Hello Brother (1999)[150]

- Lagaan (2001)

- Parineeta (2005)

- Jodhaa Akbar (2008)

- Swami (2007)[151]

- Zor Lagaa Ke...Haiya! (2009)

- Ra.One (2011)

- Kahaani (2012)

- Krrish 3 (2013)

- Mahabharat (2013)[150]

- Kochadaiiyaan (Hindi Version) (2014)

- The Ghazi Attack (2017)

- Firangi (2017)

Humanitarian causes[edit]

Bachchan has been involved with many social causes. For example, he donated ₹1.1 million to clear the debts of nearly 40 beleaguered farmers in Andhra Pradesh[152] and ₹3 million to clear the debts of some 100 Vidarbha farmers.[153] In 2010, he donated ₹1.1 million to Resul Pookutty's foundation for a medical centre at Kochi,[154][155][156] and he has given ₹250,000 ($4,678) to the family of Delhi policeman Subhash Chand Tomar who died after succumbing to injuries during a protest against gang-rape after the 2012 Delhi gang rape case.[157] He founded the Harivansh Rai Bachchan Memorial Trust, named after his father, in 2013. This trust, in association with Urja Foundation, will be powering 3,000 homes in India with electricity through solar energy.[158][159] In June 2019 he cleared debts of 2100 farmers from Bihar.[160]

Bachchan was made a UNICEF goodwill ambassador for the polio Eradication Campaign in India in 2002.[161] In 2013, he and his family donated ₹2.5 million ($42,664) to a charitable trust, Plan India, that works for the betterment of young girls in India.[162] He also donated ₹1.1 million ($18,772) to the Maharashtra Police Welfare Fund in 2013.[163]

Bachchan was the face of the 'Save Our Tigers' campaign that promoted the importance of tiger conservation in India.[164] He supported the campaign by PETA in India to free Sunder, a 14-year-old elephant who was chained and tortured in a temple in Kolhapur, Maharashtra.[165]

In 2014, it was announced that he had recorded his voice and lent his image to the Hindi and English language versions of the TeachAIDS software, an international HIV/AIDS prevention education tool developed at Stanford University.[166]

Business investments[edit]

Amitabh Bachchan has invested in many upcoming business ventures. In 2013, he bought a 10% stake in Just Dial from which he made a gain of 4600 percent. He holds a 3.4% equity in Stampede Capital, a financial technology firm specialising in cloud computing for financial markets. The Bachchan family also bought shares worth $252,000 in Meridian Tech, a consulting company in U.S. Recently they made their first overseas investment in Ziddu.com, a cloud based content distribution platform.[164][167] Bachchan was named in the Panama Papers and Paradise Papers, leaked confidential documents relating to offshore investment.[168][169]

Awards and honours[edit]

Apart from National Film Awards, Filmfare Awards and other competitive awards which Bachchan won for his performances throughout the years, he has been awarded several honours for his achievements in the Indian film industry. In 1991, he became the first artist to receive the Filmfare Lifetime Achievement Award, which was established in the name of Raj Kapoor. Bachchan was crowned as Superstar of the Millennium in 2000 at the Filmfare Awards.

In 1999, Bachchan was voted the "greatest star of stage or screen" in a BBC Your Millennium online poll. The organisation noted that "Many people in the western world will not have heard of [him] ... [but it] is a reflection of the huge popularity of Indian films."[170] In 2001, he was honoured with the Actor of the Century award at the Alexandria International Film Festival in Egypt in recognition of his contribution to the world of cinema.[171] Many other honours for his achievements were conferred upon him at several International Film Festivals, including the Lifetime Achievement Award at the 2010 Asian Film Awards.[172]

In June 2000, he became the first living Asian to have been modelled in wax at London's Madame Tussauds Wax Museum.[173] Another statue was installed in New York in 2009,[174] Hong Kong in 2011,[175] Bangkok in 2011,[176] Washington, DC in 2012,[177] and Delhi, in 2017.[178]

In 2003, he was conferred with the Honorary Citizenship of the French town of Deauville.[179] The Government of India awarded him with the Padma Shri in 1984, the Padma Bhushan in 2001 and the Padma Vibhushan in 2015. The then-President of Afghanistan awarded him the Order of Afghanistan in 1991 following the shooting of Khuda Gawah there.[180] France's highest civilian honour, the Knight of the Legion of Honour, was conferred upon him by the French Government in 2007 for his "exceptional career in the world of cinema and beyond".[181] On 27 July 2012, Bachchan carried the Olympic torch during the last leg of its relay in London's Southwark.[182]

Several books have been written about Bachchan.

- Amitabh Bachchan: the Legend was published in 1999,[183]

- To be or not to be: Amitabh Bachchan in 2004,[184]

- AB: The Legend (A Photographer's Tribute) in 2006,[185]

- Amitabh Bachchan: Ek Jeevit Kimvadanti in 2006,[186]

- Amitabh: The Making of a Superstar in 2006,[187]

- Looking for the Big B: Bollywood, Bachchan and Me in 2007[188] and

- Bachchanalia in 2009.[189]

Bachchan himself wrote a book in 2002: Soul Curry for you and me – An Empowering Philosophy That Can Enrich Your Life.[190] In the early 80s, Bachchan authorised the use of his likeness for the comic book character Supremo in a series titled The Adventures of Amitabh Bachchan.[191] In May 2014, La Trobe University in Australia named a Scholarship after Bachchan.[192]

He was named "Hottest Vegetarian" by PETA India in 2012.[193] He won the title of "Asia's Sexiest Vegetarian" in a contest poll run by PETA Asia.[194]

In Allahabad, the Amitabh Bachchan Sports Complex and Amitabh Bachchan Road are named after him.[195][196] A government senior secondary school in Saifai, Etawah is called Amitabh Bachchan Government Inter College.[197][198][199] There is a waterfall in Sikkim known as Amitabh Bachchan Falls.[200]

There is a temple in Kolkata, where Amitabh is worshipped as a God.[201][202]

See also[edit]

Other articles of the topic Bollywood : Josh (2000 film)

Other articles of the topic Biography : Kayden James Buchanan, Bankrol Hayden, Muhammad Nasiruddin al-Albani, Icewear Vezzo, List of Mensans, 27 Club, Tony Tinderholt

Some use of "" in your query was not closed by a matching "".Some use of "" in your query was not closed by a matching "".

- List of awards and nominations received by Amitabh Bachchan

- List of Bollywood actors

- List of Indian film actors

Explanatory notes[edit]

- ↑ The Times of India is incorrect: अमिताभ (cf. the name of the Buddha Amitābha) means "(one) whose light is infinite (literally: immeasurable)" while "(one) whose light will never die (i.e. is immortal)" would be: अमृताभ; "immeasurable light" and "immortal light" would be अमिताभा and अमृताभा respectively which could not be used as masculine names since they are feminine compound nouns.

References[edit]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 James, Anu (25 February 2015). "Amitabh Bachchan, Kamal Haasan, Katrina Kaif and Other Bollywood Celebs Who Changed Their Names [PHOTOS]". Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- ↑ "Alumni meet at Kirori Mal College". The Times of India. 26 February 2010.

- ↑ Bhatia, Shreya (6 January 2020). "Meet the world's richest movie star, an Indian: Shah Rukh Khan". Gulf News. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

- ↑ Dedhia, Sonil (7 October 2012). "Amitabh Bachchan: No resolutions for my birthday". Rediff. Retrieved 9 October 2019.

On October 2, the superstar took time out to give interviews to the media, as celebrations for his 70th birthday on October 11[, 2012,] started picking up

- ↑ "Amitabh Bachchan at 73: An ode to the undisputed 'Shahenshah' of Bollywood". The Indian Express. 11 October 2015. Retrieved 11 October 2015.

- ↑ "Rajinikanth reveres Amitabh Bachchan as the 'Emperor of Indian Cinema'!". indiaglitz.com. 10 October 2015. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- ↑ "Delhi's date with Big B at Adda on Friday". The Independent. 27 September 2012. Retrieved 27 September 2012.

- ↑ "Amitabh Bachchan: A Life in Pictures". Bafta.org. Archived from the original on 28 December 2011. Retrieved 23 March 2012. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ "Amitabh Bachchan: Meet the biggest movie star in the world". The Independent. 9 February 2015. Retrieved 9 February 2015.

- ↑ "Why Amitabh Bachchan is more than a superstar". BBC. 11 October 2012. Retrieved 11 October 2012.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Wajihuddin, Mohammed (2 December 2005). "Egypt's Amitabh Bachchan mania". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 1 May 2013. Retrieved 22 November 2011. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ Jatras, Todd (9 March 2001). "India's Celebrity Film Stars". Forbes. Retrieved 22 November 2011.

- ↑ "Bachchan Receives Lifetime Achievement Award at DIFF". Khaleej Times. 25 November 2009. Archived from the original on 2 June 2013. Retrieved 24 November 2011. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ "Truffaut labeled Bachchan a one-man industry". China Daily. Archived from the original on 1 February 2008. Retrieved 1 February 2008. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ Willis, Andrew (2004). Film Stars: Hollywood and Beyond. Manchester University Press. p. 4. ISBN 9780719056451. Search this book on

- ↑ "As more satellite TV networks target Asia, the picture is one of confusion and uncertainty". India Today. 30 September 1993.

- ↑ Sinanan, Anil (23 July 2008). "The Bachchans in TNT: it's dynamite!". The Times. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- ↑ "INDIA's biggest superstar Amitabh Bachchan has no interest in celebrating his 77th birthday". pressreader.com. 13 October 2019. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- ↑ Masih, Archana (9 October 2012). "Take a tour of Amitabh's home in Allahabad". Rediff.com. Retrieved 14 February 2014.

- ↑ "Jaya inaugurates library in memory of Harivansh Rai Bachchan". OneIndia.com. Greynium Information Technologies Pvt. Ltd. 6 March 2006. Retrieved 18 November 2015.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Mishra, Vijay (2002). Bollywood Cinema: Temples of Desire. Psychology Press. p. 131. ISBN 9780415930147. Search this book on

- ↑ West-Pavlov, Russell (2018). The Global South and Literature. Cambridge University Press. p. 167. ISBN 9781108246316. Search this book on

- ↑ "Amitabh was initially named Inquilaab". The Times of India. 28 August 2012.

- ↑ "I am proud of my surname Amitabh Bachchan". 28 July 2011. Retrieved 26 July 2017.

- ↑ Bachchan, Harivansh Rai (1998). In The Afternoon Time. Viking Pr. ISBN 978-0670881581. Search this book on

- ↑ Khan, Alifiya. "Teji Bachchan passes away". Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on 25 December 2007. Retrieved 10 February 2011. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ "Amitabh Bachchan's journey to the top". India Today. 10 October 2009.

- ↑ "Reviews on: To Be or Not To Be Amitabh Bachchan – Khalid Mohamed".

- ↑ "Hindi classics that defined the decade: 1960s Bollywood was frothy, perfectly in tune with the high spirits of the swinging times". The Indian Express. 31 October 2017.

- ↑ Raj, Ashok (2009). Hero Vol.2. Hay House. p. 21. ISBN 9789381398036. Search this book on

- ↑ Before Brando, There Was Dilip Kumar, The Quint, December 11, 2015

- ↑ Kumar, Surendra (2003). Legends of Indian cinema: pen portraits. Har-Anand Publications. p. 51. Search this book on

- ↑ "Amitabh Bachchan and Jaya Bachchan's love story | The Times of India". The Times of India. Retrieved 10 January 2018.

- ↑ Suresh Kohli (17 May 2012). "Arts / Cinema: Bhuvan Shome (1969)". The Hindu. Chennai, India. Archived from the original on 5 February 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2012. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ Ramnath, Nandini. "Before stardom: Amitabh Bachchan's drudge years are a study in perseverance and persona building". Scroll.in. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- ↑ Avijit Ghosh (7 November 2009). "Big B's debut film hit the screens 40 yrs ago, today". The Times of India. Retrieved 11 December 2012.

- ↑ "I felt I did a good job in Black". Rediff.com. 9 August 2007. Retrieved 24 March 2012.

- ↑ "Box Office 1972". Box Office India. 12 October 2012. Archived from the original on 12 October 2012. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- ↑ Bombay to Goa

- ↑ [1][dead link]

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 "80 iconic performances 1/10". 1 June 2010. Archived from the original on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 29 November 2011. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ Lokapally, Vijay (22 December 2016). "Sanjog (1972)". The Hindu. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 43.2 43.3 43.4 "Revisiting Prakash Mehra's Zanjeer: The film that made Amitabh Bachchan". The Indian Express. 20 June 2017.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 "Why Salim Khan was angry with Amitabh Bachchan". The Times of India. 13 December 2013.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 45.2 "Deewaar was the perfect script: Amitabh Bachchan on 42 years of the cult film". Hindustan Times. 29 January 2017.

- ↑ "Film legend promotes Bollywood". BBC News. 23 April 2002. Retrieved 15 January 2010.

- ↑ "Box Office 1973". Box Office India. Archived from the original on 20 October 2013. Retrieved 12 November 2013. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ "the angry young man in Hindi cinema – Lal Salaam: A Blog by Vinay Lal". vinaylal.wordpress.com. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- ↑ Narcisa, Maanvi. "The 'Angry Young Man' of 'Zanjeer': From Osborne to Bachchan". Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- ↑ "Why Amitabh Bachchan is more than a superstar". BBC. 11 October 2012. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- ↑ Tieber, Claus (21 August 2015). "Writing the Angry Young Man: Salim-Javed's screenplays for Amitabh Bachchan". Retrieved 21 July 2018 – via ResearchGate.

- ↑ "Filmfare Awards Winners 1974: Complete list of winners of Filmfare Awards 1974". The Times of India. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- ↑ Box Office India.Archived 20 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Box Office 1975". BoxOffice India.com. Archived from the original on 20 October 2013. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ 55.0 55.1 Kanwar, Rachna (3 October 2005). "25 Must See Bollywood Movies". Indiatimes movies. Archived from the original on 15 October 2007. Retrieved 6 December 2007. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ "Sholay". International Business Overview Standard. Archived from the original on 30 June 2012. Retrieved 6 December 2007. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ "Top Actor". 2 January 2015. Archived from the original on 2 January 2015. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- ↑ "Box Office 1983". Box Office India. 29 October 2013. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- ↑ "Box Office 1977". Box Office India. Archived from the original on 12 October 2012. Retrieved 11 December 2012. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ [2][dead link]

- ↑ List of Bollywood films of 1978#Top-grossing films

- ↑ "Oprice.in, Celebrities: The $400 Million USD : Amitabh Bachchan Net Worth". Oprice.in. Retrieved 10/02/2022. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help)In 2022, Amitabh Bachchan's Net Worth has touched a new height of $400 Million Dollars. - ↑ "BoxOffice India.com". BoxOffice India.com. Archived from the original on 2 January 2010. Retrieved 15 January 2010. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ "Box Office 1981". Box Office India. Archived from the original on 28 September 2013. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ "Box Office 1983". Box Office India. Archived from the original on 28 September 2013. Retrieved 28 January 2015. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ "Highest Grossing Hindi Movies of 1983". IMDb. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- ↑ SM, Mitesh Shah aka. "List of 40 All Time Super hit movies of Amitabh Bachchan". realityviews.in. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ↑ "Bachchan injured whilst shooting scene". Rediff.com. Archived from the original on 4 March 2007. Retrieved 11 March 2007. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ "Amitabh Bachchan no longer excited about birthdays". Hindustan Times. 10 October 2009. Retrieved 11 December 2012.

- ↑ "Coolie a success". Box Office India. Archived from the original on 12 January 2012. Retrieved 11 March 2007. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ "30 years after the Coolie accident: Big B's "second birthday"". Movies.ndtv.com. 2 August 2012. Archived from the original on 29 January 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2012. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ Mohamed, Khalid. "Reviews on: To Be or Not To Be Amitabh Bachchan". mouthshut.com. Retrieved 11 March 2007.

- ↑ "Top Actor". boxofficeindia.com/topactors.htm. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ "Box Office 1990". Box Office India. 21 September 2013. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- ↑ "Box office 1990". Box Office India. 21 September 2013. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- ↑ "Box Office 1994". Box Office India. Archived from the original on 7 January 2013. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ "Amitabh Bachchan – from bankruptcy to crorepati". 10 September 2011. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- ↑ "Rediff on the NeT Business News: Businessman Bachchan braves a bad patch as ABCL falls sick". Rediff.com. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- ↑ "Collapse of Mrityudaata diminishes Amitabh Bachchan's godlike status". India Today. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- ↑ "After dream venture ABCL go bankrupt, Amitabh Bachchan faces legal battle with creditors". India Today. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- ↑ "Rediff on the NeT Business News: Businessman Bachchan braves a bad patch as ABCL falls sick". Rediff.com. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- ↑ Patil, Vimla (4 March 2001). "Muqaddar Ka Sikandar".

- ↑ "Major Saab – Movie". Box Office India. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- ↑ Taliculam, Sharmila. "He's back!".

- ↑ "Rediff on the NeT, Movies: A look at the year gone by". Rediff.com. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- ↑ "Amitabh and Abhishek rule the box office". Box Office India. Archived from the original on 8 July 2011. Retrieved 11 March 2007. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ "Box Office 2006". Box Office India. Archived from the original on 17 February 2012. Retrieved 11 March 2007. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ "Films fail at the BO". Box Office India. Archived from the original on 18 August 2013. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ Adarsh, Taran. "Top 5: 'Nishabd', 'N.P.D.' are disasters". Bollywood Hungma. Archived from the original on 14 January 2009. Retrieved 26 March 2007. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ "Shootout at Lokhandwala – Movie". Box Office India. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- ↑ "Box Office 2007". Box Office India. 15 January 2013. Archived from the original on 15 January 2013. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- ↑ "Cheeni Kum – Movie –". Box Office India. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- ↑ 93.0 93.1 "Box Office 2007". Box Office India. Archived from the original on 9 November 2013. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ "This is Amitabh's best performance after Black".[permanent dead link]

- ↑ "Amitabh Bachchan to star with Johnny Depp". ourbollywood.com. Archived from the original on 1 April 2007. Retrieved 11 March 2007. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ Akbar, Arifa (13 November 2009). "Underworld tale won't see light of day". The Independent. London. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ↑ "Top India Total Nett Gross 2009 –". Box Office India. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- ↑ "Major Ravi gets ready to shoot Kandahar: Rediff.com Movies". Rediff.com. 8 June 2010. Retrieved 2 October 2010.

- ↑ "Big B in 'Kandahaar' along with Sunil Shetty". indiaglitz.com. 14 April 2010.

- ↑ "Amitabh to forego fee for sharing screen with Mohanlal". The Indian Express. 17 April 2010.

- ↑ "Piku Total Collection – Lifetime Business – Total Worldwide Collection – Box Office Hits". 10 June 2015. Archived from the original on 22 July 2018. Retrieved 21 July 2018. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ "Amitabh Bachchan boosts Piku box office collections to over Rs 100 cr, slowly, steadily". 11 May 2015. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- ↑ Mehta, Ankita (21 May 2015). "'Piku' 13 Days Box Office Collection: Deepika-Amitabh Starrer Grosses ₹100 Crore Worldwide". Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- ↑ "'PIKU' Review: Must-watch for the thundering trio of Amitabh Bachchan, Deepika Padukone, and Irrfan Khan". 8 May 2015. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- ↑ "Review: In 'Piku,' Amitabh Bachchan Plays a Dad to Deepika Padukone". Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- ↑ Rockstah Media. "Poop dreams – Rajeev Masand – movies that matter : from bollywood, hollywood and everywhere else". rajeevmasand.com. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- ↑ McCahill, Mike (18 May 2015). "Piku review: Amitabh Bachchan lets it all out in constipation comedy". The Guardian. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- ↑ "Pink review: Amitabh Bachchan is still the only boss around". 15 September 2016. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- ↑ 109.0 109.1 "Pink review by Anupama Chopra: A tale of true grit, grippingly told". 16 September 2016. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- ↑ "Pink movie review: Amitabh Bachchan's POWERFUL message is unmissable". India Today. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- ↑ "Box Office Verdict 2016 – Hits & Flops of the Year". 27 January 2017. Archived from the original on 22 July 2018. Retrieved 21 July 2018. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ Hungama, Bollywood (17 September 2016). "Box Office: Worldwide Collections and Day wise breakup of Pink – Bollywood Hungama". Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- ↑ "Review: Pink, a film that must be championed". Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- ↑ "Pink Movie Review {4.5/5}: Critic Review of Pink by Times of India". Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- ↑ "Pink Movie Review: Amitabh Bachchan Shines As Always – NDTV Movies". Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- ↑ McCahill, Mike (15 September 2016). "Pink review – subtle drama that grapples with India's rape culture". The Guardian. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- ↑ "Fatima Sana Shaikh Joins Yash Raj Films' Thugs of Hindostan Along with Amitabh Bachchan and Aamir Khan". yashrajfilms.com. Archived from the original on 3 July 2018. Retrieved 11 May 2017. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ "102 Not Out teaser: Amitabh Bachchan, Rishi Kapoor seen together on-screen after 27 years- Entertainment News, Firstpost". 9 February 2018. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- ↑ "Amitabh Bachchan: Teaming up with Rishi Kapoor for '102 Not Out' has been a great joy". Archived from the original on 25 July 2018. Retrieved 21 July 2018. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ "Sony Pictures boards Indian comedy '102 Not Out' with Amitabh Bachchan, Rishi Kapoor". Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- ↑ "Karan Johar announces his upcoming film trilogy with Amitabh Bachchan, Ranbir Kapoor and Alia Bhatt – Movies to look forward to | The Times of India". The Times of India. Retrieved 11 March 2018.

- ↑ "Amitabh Bachchan: Stint in Politics". Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on 9 January 2006. Retrieved 5 December 2005. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ "Interview with Amitabh Bachchan". sathnam.com. Archived from the original on 31 May 2009. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ "Bofors scam: Amitabh, Jaya Bachchan react to whistle-blower's revelations". 25 April 2012.

- ↑ "Bachchan has no plans for the election." The Hindu.

- ↑ "Bollywood's Bachchan in trouble over crime claim". Agence France-Presse. 4 October 2007. Archived from the original on 16 January 2008. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ "The 15-year ban on Bachchan!". Oldbh.bollywoodhungama.com. 27 January 2007. Retrieved 24 March 2012.[permanent dead link]

- ↑ "US federal court summons Amitabh Bachchan in an alleged human rights violation; connects it to the 1984 anti-Sikh riots". News18. 26 February 2015. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- ↑ "1984 riots: Amitabh Bachchan summoned by US court for 'instigating' violence against Sikhs". The Times of India.

- ↑ "Amitabh Bachchan summoned by Los Angeles court". The National.

- ↑ "US court summons Amitabh Bachchan in connection with 1984 anti-Sikh riots". Deccan Chronicle.

- ↑ "US court summons Amitabh Bachchan for 'instigating' 1984 anti-Sikh riots". Dawn. Pakistan. 28 October 2014. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- ↑ Saxena, Poonam (19 November 2011). "Five crore question: What makes KBC work?". Hindustan Times. Retrieved 24 November 2011.

- ↑ "India scraps millionaire TV show". BBC News. 25 January 2006. Retrieved 7 May 2010.

- ↑ "Amitabh Bachchan back on TV with 'Bigg Boss 3'". The Times of India. Retrieved 5 September 2009.

- ↑ "KBC 4 beats Bigg Boss 4 in its final episode". One India. 13 December 2010. Archived from the original on 14 July 2012. Retrieved 13 March 2011. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ Darpan, Pratiyogita (1 September 2001). "The Indian Telly Awards – 'Kaun Banega Crorepati'".

- ↑ Team, Tellychakkar. "TV News". Tellychakkar.com. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- ↑ "Watch: Amitabh Bachchan battles world, himself in TV show 'Yudh'". The Indian Express. 2 May 2014.

- ↑ "Amitabh Bachchan to get copyright: Celebrities, News". India Today. 8 November 2010. Retrieved 11 December 2012.

- ↑ "Amitabh Bachchan lends his voice to animated 'Mahabharat'". The Indian Express. 12 March 2012. Retrieved 11 December 2012.

- ↑ "Near 70, Amitabh Bachchan still gets mobbed". The Indian Express. 29 September 2012. Retrieved 11 December 2012.

- ↑ hindustantimes.in "Amitabh voice for Shatranj Ke Khiladi." Hindustan Times. Archived 6 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Ashutosh had rejected Big B as Lagaan's narrator". The Times of India. 16 June 2011.

- ↑ "Amitabh to get France's highest civilian honour: Bollywood News". ApunKaChoice.Com. 12 October 2006. Archived from the original on 10 March 2012. Retrieved 14 February 2011. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ "Amitabh to do voiceover for Jodhaa-Akbar". 17 January 2008.

- ↑ Singh, Sunny (2018). Amitabh Bachchan. Palgrave. p. 171. ISBN 978-1-84457-631-9. Search this book on

- ↑ "Amitabh to do voiceover for Jodhaa-Akbar". 17 January 2008.

- ↑ "Bhuvan Shome 1969". 10 February 2013. Archived from the original on 6 March 2018. Retrieved 6 March 2018. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ 150.0 150.1 "Amitabh Bachchan Movies List". 27 May 2016.

- ↑ Subhash K Jha (17 January 2008). "Big B to lend voice to Jodhaa Akbar". Hindustan Times.

- ↑ "Big B's secret aspect finally revealed". The Times of India. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- ↑ "The Amitabh Bachchan way or the highway – Aditi Prasad – The Sunday Indian". thesundayindian.com. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- ↑ "Amitabh Bachchan announces 11 lakh contribution for Resul Pookutty's foundation". DNA India. 7 February 2010. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- ↑ "Amitabh Bachchan supports medical centre at Kochi". dna. 8 February 2010.

- ↑ Padmanabhan, Geeta (21 January 2011). "The Saturday Interview – Sound Sense". The Hindu.

- ↑ MumbaiDecember 26, P. T. I.; December 26, 2012UPDATED; Ist, 2012 11:40. "Delhi gangrape: Amitabh Bachchan donates Rs 2.5 lakh to Delhi Police constable Subhash Chand Tomar's family". India Today. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- ↑ "Amitabh Bachchan opens memorial trust in father's name – Indian Express". The Indian Express. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- ↑ "Amitabh Bachan plans to light 3000 homes with Solar Power". renewindians.com. Archived from the original on 17 April 2018. Retrieved 16 April 2018. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ "Amitabh Bachchan pays off loans of 2,100 Bihar farmers, promises to help kin of Pulwama victims". The Economic Times. 12 June 2019. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- ↑ "Amitabh Bachchan launches new Polio Communication Campaign". UNICEF. 16 December 2011.

- ↑ "Bachchan's charity side". Hindustan Times. 10 February 2013. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- ↑ "Maharashtra police keep Big B 'waiting'". The New Indian Express.

- ↑ 164.0 164.1 "20 reasons why we love Amitabh Bachchan". The Times of India.

- ↑ "Amitabh Bachchan, Madhuri Dixit back 'Free Sunder' campaign". NDTV.com.

- ↑ "Amitabh Bachchan Joins S.F. Bay Area Nonprofit TeachAIDS". India West. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- ↑ "Actors turn investors: Bachchans make first ever overseas investment with Ziddu.com". Firstpost.

- ↑ Tandon, Suneera (7 November 2017). "The Indian superstars of tax haven leaks: Amitabh Bachchan and Vijay Mallya". Quartz India. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- ↑ "Amitabh Bachchan, Family May Be Summoned in Panama Papers Case". NDTV. 27 September 2017. Retrieved 10 November 2017.

- ↑ "ENTERTAINMENT | Bollywood star tops the poll". BBC News. 1 July 1999. Archived from the original on 10 September 2010. Retrieved 2 October 2010. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ "The Tribune, Chandigarh, India – World". The Tribune. 4 September 2001. Archived from the original on 21 November 2013. Retrieved 2 October 2010.

- ↑ "Actor Amitabh Bachchan | Film Paa – Oneindia Entertainment". Entertainment.oneindia.in. 25 March 2010. Archived from the original on 24 May 2013. Retrieved 2 October 2010. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ "Art of cinema is a small contribution: Amitabh Bachchan". Screenindia.com. 1 April 2009. Archived from the original on 4 June 2009. Retrieved 2 October 2010. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ "Amitabh Wax figure in New York". Whatslatest.com. Archived from the original on 2 December 2012. Retrieved 2 October 2010. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ "Amitabh's wax statue unveiled at Hong Kong Tussauds". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 25 March 2011. Retrieved 11 October 2012.

- ↑ "Unveils wax figure of India's all-time superstar: Amitabh Bachchan". madametussauds.com/Bangkok. 24 August 2011. Archived from the original on 14 November 2012. Retrieved 12 October 2012. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ "Big B, SRK, Aishwarya's wax figures at Washington Tussauds". The Indian Express. 5 December 2012. Retrieved 5 December 2012.

- ↑ "Amitabh Bachchan misunderstands his wax statue at Madame Tussauds, Delhi as his photo". The Times of India. 13 January 2017. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- ↑ "'Shahenshah' of Bollywood". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 4 July 2003. Archived from the original on 14 October 2010. Retrieved 2 October 2010. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ "Indian film star Amitabh Bachchan cherish Afghanistan memories". 27 August 2013.

- ↑ Pandey, Geeta (27 January 2007). "South Asia | French honour for Bollywood star". BBC News. Retrieved 2 October 2010.

- ↑ Bhushan, Nyay (26 July 2012). "Amitabh Bachchan Carries Olympic Torch". The Hollywood Reporter.

- ↑ "Amitabh Bachchan – The Legend by Bhawana Somaaya". Indiaclub.com. Archived from the original on 15 June 2013. Retrieved 2 October 2010. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ halid Mohamed. "To Be or Not to Be Amitabh Bachchan". Shvoong.com. Retrieved 2 October 2010.

- ↑ AB: The Legend (A Photographer's Tribute). Exoticindiaart.com. 2 October 2008. Retrieved 2 October 2010. Search this book on

- ↑ Somaaya (20 October 2009). Amitabh Bachchan: Ek Jeevit Kimvadanti. Autsun.Com. Macmillan India. ISBN 978-1-4039-3160-3. Archived from the original on 7 July 2011. Retrieved 2 October 2010. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) Search this book on

- ↑ "Amitabh: The Making of a Superstar by Susmita Dasgupta". Indiaclub.com. Archived from the original on 15 June 2013. Retrieved 2 October 2010. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ Looking for the Big B: Bollywood, Bachchan and Me: Amazon.co.uk: Jessica Hines: Books. ASIN 0747560412. Search this book on

- ↑ "Amitabh Bacchan: A book on Amitabh Bachchan launched 'Bachchanalia'". Amitabbacchan.blogspot.com. 5 January 2009. Retrieved 2 October 2010.

- ↑ "Soul Curry for you and me – An Empowering Philosophy That Can Enrich Your Life by Amitabh Bachchan". Indiaclub.com. 11 October 1942. Archived from the original on 20 December 2010. Retrieved 2 October 2010. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (help) - ↑ "Remembering Amitabh, the Supremo superhero". Rediff.com. 10 November 2009. Retrieved 11 December 2012.

- ↑ "La Trobe University of Australia names scholarship after Amitabh Bachchan". news.biharprabha.com. Indo-Asian News Service. Retrieved 2 May 2014.

- ↑ "Amitabh Bachchan, Vidya Balan named hottest vegetarians". Hindustan Times. 3 January 2013.

- ↑ "Faye Wong is Asia's sexiest vegetarian". The Times of India. 19 June 2008.

- ↑ "Amitabh Bachchan Sports Complex". Retrieved 15 August 2016.

- ↑ "Rename Clive Road as Amitabh Bachchan Marg". 8 April 2017.

- ↑ "Neighbours' Envy: Remarkable growth of Saifai has left other villages feeling left out". 18 January 2014. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- ↑ "An oasis in undeveloped Yadav belt". Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- ↑ "The Telegraph – Calcutta : Nation". The Telegraph. Kolkota. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- ↑ Shriaya Dut (31 August 2019). "Been to Amitabh Bachchan waterfall in Sikkim, even Big B is shocked". The Tribune.

- ↑ "These are the 7 most unusual temples in India". India Today. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

- ↑ "Amitabh Bachchan's Kolkata Temple". Business Insider. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

Further reading[edit]

- Mazumdar, Ranjani. Bombay Cinema: An Archive of the City. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007 ISBN 978-0-8166-4942-6 Search this book on

.

. - Bhawana Somaaya (1 February 1999). Amitabh Bachchan: The Legend. Macmillan India Limited. ISBN 978-0-333-93355-8. Search this book on

- Bhawana Somaaya (2009). Bachchanalia: The Films and Memorabilia of Amitabh Bachchan. Osian's-Connoisseurs of Art. ISBN 978-81-8174-027-4. Search this book on

- Roy, S. (2006). "An Exploratory Study in Celebrity Endorsements". Journal of Creative Communications. 1 (2): 139–153. doi:10.1177/097325860600100201. ISSN 0973-2586.

- Kavi, Ashok Row (2008). "The Changing Image of the Hero in Hindi Films". Journal of Homosexuality. 39 (3–4): 307–312. doi:10.1300/J082v39n03_15. ISSN 0091-8369. PMID 11133139.

- Rao, R. Raj (2008). "Memories Pierce the Heart". Journal of Homosexuality. 39 (3–4): 299–306. doi:10.1300/J082v39n03_14. ISSN 0091-8369. PMID 11133138.

- Mishra, Vijay; Jeffery, Peter; Shoesmith, Brian (1989). "The actor as parallel text in Bombay cinema". Quarterly Review of Film and Video. 11 (3): 49–67. doi:10.1080/10509208909361314. ISSN 1050-9208.

- RAJADHYAKSHA, Ashish (2003). "The 'Bollywoodization' of the Indian cinema: cultural nationalism in a global arena". Inter-Asia Cultural Studies. 4 (1): 25–39. doi:10.1080/1464937032000060195. ISSN 1464-9373.

- Mallapragada, M. (2006). "Home, homeland, homepage: belonging and the Indian-American web". New Media & Society. 8 (2): 207–227. doi:10.1177/1461444806061943. ISSN 1461-4448.

- Gopinath, Gayatri (2008). "Queering Bollywood". Journal of Homosexuality. 39 (3–4): 283–297. doi:10.1300/J082v39n03_13. ISSN 0091-8369. PMID 11133137.

- Jain, Pankaj (2009). "FromKil-Arni to Anthony: The Portrayal of Christians in Indian Films". Visual Anthropology. 23 (1): 13–19. doi:10.1080/08949460903368887. ISSN 0894-9468.

- Punathambekar, Aswin (2010). "Reality TV and Participatory Culture in India". Popular Communication. 8 (4): 241–255. doi:10.1080/15405702.2010.514177. ISSN 1540-5702.

- Aftab, Kaleem (2002). "Brown: the new black! Bollywood in Britain". Critical Quarterly. 44 (3): 88–98. doi:10.1111/1467-8705.00435. ISSN 0011-1562.

- Jha, Priya (2003). "Lyrical Nationalism: Gender, Friendship, and Excess in 1970s Hindi Cinema". The Velvet Light Trap. 51 (1): 43–53. doi:10.1353/vlt.2003.0007. ISSN 1542-4251.

- Jones, Matthew (2009). "Bollywood, Rasa and Indian Cinema: Misconceptions, Meanings and Millionaire". Visual Anthropology. 23 (1): 33–43. doi:10.1080/08949460903368895. ISSN 0894-9468.

- Garwood, Ian (2006). "The Songless Bollywood Film". South Asian Popular Culture. 4 (2): 169–183. doi:10.1080/14746680600797210. ISSN 1474-6689.

External links[edit]

![]() Media related to [[commons:Lua error in Module:WikidataIB at line 466: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value).|Lua error in Module:WikidataIB at line 466: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value).]] at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to [[commons:Lua error in Module:WikidataIB at line 466: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value).|Lua error in Module:WikidataIB at line 466: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value).]] at Wikimedia Commons

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Amitabh Bachchan |

- Amitabh Bachchan's official blog

- Amitabh Bachchan on IMDb

- Amitabh Bachchan at Bollywood Hungama

- Amitabh Bachchan on TwitterLua error in Module:WikidataCheck at line 23: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value).

- British Academy of Film and Television Arts brochure

- Blanked or modified

- Amitabh Bachchan

- 1942 births

- Officiers of the Légion d'honneur

- Male actors in Hindi cinema

- Male actors from Mumbai

- Indian actor-politicians

- Indian amateur radio operators

- Indian male film actors

- Hindi film producers

- Indian male singers

- Bollywood playback singers

- Indian television presenters

- Indian male voice actors

- Best Actor National Film Award winners

- Male actors from Allahabad

- Punjabi people

- Recipients of the Padma Bhushan in arts

- Recipients of the Padma Shri in arts

- Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?

- 8th Lok Sabha members

- Lok Sabha members from Uttar Pradesh

- Recipients of the Padma Vibhushan in arts

- Indian male film singers

- People named in the Panama Papers

- Film producers from Mumbai

- 20th-century Indian male actors

- 21st-century Indian male actors

- Male actors in Hindi television

- Indian male television actors

- 20th-century Indian singers

- 21st-century Indian singers

- Singers from Mumbai

- Politicians from Allahabad

- Musicians from Allahabad

- Film producers from Uttar Pradesh

- Residents of New Alipore

- Filmfare Awards winners

- Indian Hindus

- 20th-century male singers

- Dadasaheb Phalke Award recipients

- Actors from Mumbai